[ 10 ]

Language: Did They Just Say That?

In this chapter, I’ll give you recommendations on how to record and analyze interviews, paying special attention to the words people utter, their sentence construction, and what this tells us about their level of sophistication in a subject area.

Remember, when it comes to language (Figure 10-1), we’re considering these questions:

- What are the words your customers use the most?

- What meaning are they associating with those words?

- How sophisticated are the words they are using? What level of expertise in the subject matter does that imply?

- Are they using the same lexicon that we (as the internal product designers) use? Are we using any jargon that they might find difficult to understand?

Figure 10-1

Language and language processing

Recording Interviews

As I’ve mentioned, when conducting contextual inquiries, I recommend recording interviews. This does not have to be fancy. Sure, wireless mics can come in handy, but in truth, a two hundred dollar camcorder can actually give you quite decent audio. It’s compact and unobtrusive, making it a great way to record interviews, both audio and video. Try to keep your setup as simple as possible so it’s as unobtrusive to the participant as possible and minimally affects their performance. With a little creativity, you can play back the video now in a number of tools (e.g., a Zoom conference) and get a transcription, too.

Prepping Raw Data: But, But, But…

After recording your interviews, if you analyze those transcripts for word usage and frequency, you’re going to find that, unedited, the top words that people use are “but,” “and,” “or,” and other completely irrelevant words. Obviously what we care about is the words people use for representing ideas. So strip out all the conjunctions and other small words to get at the words that are most relevant to your product or service. Then examine how commonly used those words are.

Often, word usage differs by group, age, life status, etc.; we want to know those differences. We also want to get, through the words people are using, a sense of how much they really understand the issue at hand. There are new tools popping up all the time to measure word frequency in a passage of text. I’d recommend you Google “word frequency analysis” to find the latest.

Reading Between the Lines: Sophistication

The language we use as product and service designers can make a customer either trust or mistrust us. As customers, we are often surprised by the words that a product or service uses. Thankfully, the reverse is also true; when we get the language right and synchronize our words with those of our customers, they are more confident in what we’re offering.

When we read between the lines of what someone is saying, we can “hear” their understanding of the subject matter, and this tells us about their level of sophistication. Ultimately, this leads to the right level of discussion to be having with this customer about the subject matter.

This holds for digital security or cryptography, or scrapbooking, or French cuisine. All of us have expertise in one thing or another, and use language that’s commensurate with that expertise. I’m a DSLR camera fan, and love to talk about “F stops” and “anaphoric lenses” and “ND filters,” none of which may mean anything to you. I’m sure you have expertise in something I don’t, and I have much to learn from you.

As product and service designers, what we really want to know is, what is our typical customer’s understanding of the subject matter? Then we can level-set the way we’re talking with them about the problem they’re trying to solve.

In the tax world, for example, we have tax professionals who know that Section 368 of “the code” (the US Internal Revenue Service tax code) is all about corporate reorganizations and acquisitions, and might know how a Revenue Procedure (or “Rev Proc”) from 1972 helps to “moderate the cost-basis” for a certain tax computation. These individuals are often shocked that other humans aren’t as passionate about the tax code, and are horrified that some people just want TurboTax to tell them how to file without revealing the inner workings of the tax system in all its complexities. TurboTax speaks to nonexperts in terms they can understand—e.g., What was your income this year? Do you have a farm? Did you move?

The bottom-line message here is, learn what your customers are saying, what that implies about their expertise in the subject matter, and meet your customers where they are, using terms they can understand.

Case Study: Medical Terms

Challenge: You may have heard of MedlinePlus, which is a part of

NIH.gov. The website, depicted in Figure 10-2, provides an excellent and comprehensive list of different medical issues. The challenge we found for users of the site was that MedlinePlus listed medical situations by their formal names, like “TIA” or “transient ischemic attack,” which is the accurate name for what most people would call a “mini-stroke.” If NIH had only listed TIA, the average user of the site would likely be unable to find what they were looking for in a list of search results.

Figure 10-2

MedlinePlus

Recommendation: We advised the NIH to have its search function work both for formal medical titles and more common vernacular. We knew that both sets of terms should be prominently presented, because if someone was looking for “mini-stroke” and didn’t see it immediately, they would probably feel like they got the wrong result. A lot of times, experts internal to a company (and doctors at NIH, and tax accountants at a law firm) will struggle with including more colloquial language because it may not be strictly accurate, but I would argue that as designers, we should lean more toward accommodating the novices than the experts if we must choose between the two options. Or, if you can, follow the style of Cancer.gov that I mentioned in Chapter 5, where for each medical condition users have the choice of viewing either the health professional version or the patient version.

Real-World Examples

Looking again at our sticky notes, Figures 10-3–10-5 show the ones we should place in the Language column:

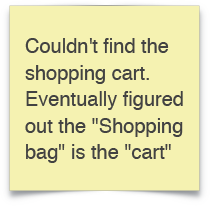

“Couldn’t find the shopping cart. Eventually figured out the ‘Shopping bag’ is the cart.”

If we know that a “shopping cart” feature is present on our site, there are two possible reasons why the participant was unable to find it: (a) there was a visual issue that prevented them from actually seeing the feature, or (b) they were staring at the correct feature, yet did not understand that what they were looking at was what they were looking for because they were expecting to see a different term (i.e., “shopping bag” versus “shopping cart”). To discern which your site should have, you’ll want to consult your notes or video footage to see where the user was actually looking at this moment. In this case, my notes indicated that the user eventually figured out the “shopping bag” was the “cart,” suggesting that this was indeed a language issue.

This one is a great example of how the same word in English can mean different things in America, versus Canada, versus the UK, etc. Many of us in America say “shopping cart” with visions of Costco and SUV-sized carts in our heads, but in many parts of the world where public transit is the norm, shopping bags prevail. With this type of finding, we would want to know if other participants had a similar issue to determine if we should change the terminology.

Figure 10-3

Research observation: participant using different terms

“Searched for ‘Eames Midcentury Lounge Chair’ when asked to search for a chair.”

Here, I would argue it’s highly unlikely for the average shopper to know that there is something called an Eames chair, and that it’s a lounge chair, and that it’s a mid-century lounge chair. These search terms suggest to me that this person is extremely knowledgeable about mid-century modern furniture, which demonstrates the high level of expertise of this particular shopper and the type of language we might need to use to reach them. If this is a trend, we need to let content specialists know to accommodate this level of sophistication.

Figure 10-4

Research observation: search terms suggest considerable knowledge of this domain

“Wants to filter results by ‘Film noir.’”

This data point speaks to the person’s expertise in the field and the sophistication of the language and background understanding they have regarding the film industry. There’s also an element of memory here, as it points to the user’s mental model of having results organized by genre, perhaps the way a similar site organizes its results.

Figure 10-5

Research observation: search term suggests deeper knowledge of film industry

Through this exercise, I’ve given you a small taste of the breadth of the types of language responses we’re looking for. They range from misnamed buttons to cultural notions of word meanings to nomenclature associated with an interaction/navigation to level of sophistication.

Contrast your customers’ word usage with your web or app’s language, and consider how this might impact your product or service design. Due to the range of expertise that your customers’ language demonstrated, you might conclude we need the design to better reflect the needs of both novices and experts on the site.

Case Study: Institute of Museum and Library Services

Challenge: The example in Figure 10-6 demonstrates the importance of appropriate names for links, not just the content. This government-funded agency, which you probably haven’t heard of, does amazing work supporting libraries and museums across the U.S. If you look at the organization of the website navigation, it’s pretty typical: About Us, Grants, Publications, Research & Evaluation, and… Issues. When we tested this with users, what caught their eye was the Issues tab. All of our participants assumed “Issues” meant things that were going wrong at the Institute. This couldn’t be further from the truth; the Issues area actually represented the Institute’s areas of top focus and included discussion of topics relevant to museums and libraries across America (preservation, digitization, accessibility, etc.).

Figure 10-6

The Institute of Museum and Library Services website

Recommendation: The key point here is that we needed to consider matching not only the language in general to customer expectations, but also the navigational terminology. Moving forward, the Institute will move the “Issues” content to another location with a new name that better conveys the underlying content.

Concrete Recommendations

- Record all interview audio and transcribe it using an automated tool.

- Measure the frequency of word use and the level of sophistication of the vocabulary (e.g., “hurt brain” versus “left medio-parietal subdermal hematoma”) to get an indication of the sophistication of the customers’ understanding of an issue.

- Study and pay attention to word order and words used, especially when building AI systems (in order to get the appropriate training in and ensure certain syntactic patterns will be correctly processed).