[ 13 ]

Decision Making: Following the Breadcrumbs

When it comes to decision making, we’re trying to figure out what problems customers are really trying to solve and the decisions they have to make along the way (Figure 13-1). What are they trying to accomplish, and what information do they need to make a decision at this moment in time?

With decision making, we’re asking questions like:

- What is the user trying to accomplish?

- What does their overall decision-making process look like?

- What facts do they need to make their decision and solve their problem?

- What do they need at each stage of problem solving?

- When do they seem to be overwhelmed and “satisfice”?

- What middle-of-the-road, “sensible” option do they default to?

Figure 13-1

Decision making

What Am I Doing? Goals and Journeys

We want to focus on all the subgoals customers need to accomplish to get from their initial state to their final goal.

Your customer’s end goal might be to make a cake, but to get there, they are embarking on a journey with quite a few steps along the way. First, they are going to need to find a recipe, get all the ingredients, and put them together according to the recipe’s instructions. Within the recipe, there are many more steps—turning on the oven, getting out the right-sized pan, sifting the flour, mixing the dry ingredients together, etc. We want to identify each of those microsteps that are involved with our products, and how we can support our end customers in making their ultimate decision or reaching their goal.

Case Study: Ecommerce Payment

Challenge: For one client, we observed a group that was trying to decide which ecommerce payment tool to use (PayPal, Stripe, etc.). Through interviews, we collected a series of questions or concerns that people had and—you guessed it—wrote them all down on sticky notes (e.g., “What if I need help?”, “How does it work?” “Can this work with my particular ecommerce system right now?” “What are the security issues?”) There were so many microdecisions to make and questions people wanted answered before they were willing to proceed in acquiring one of these tools.

Outcome: By capturing each of these subgoals and ordering them, you can ensure your designs support the customer journey, answering each set of questions in a timely fashion. This helps your customers to trust your product/service and make a decision—ultimately giving them a better overall experience where they feel like they’re making an informed choice.

Gimme Some of That! Just-in-Time Needs

You may remember from Chapter 5 that we can be very susceptible to nonideal psychological influences when making decisions (which is why I never let myself sit in a car I’m not intending to buy). Often we get overwhelmed with choices and end up defaulting to satisficing—accepting an available option as satisfactory. That’s why people were more willing to buy the $349 blender when it was displayed in between one for $199 and one for $499. Choosing the middle option seems sensible to people. We want to keep this type of classic framing problem in mind as product designers, considering what the “sensible” option may be for our customers.

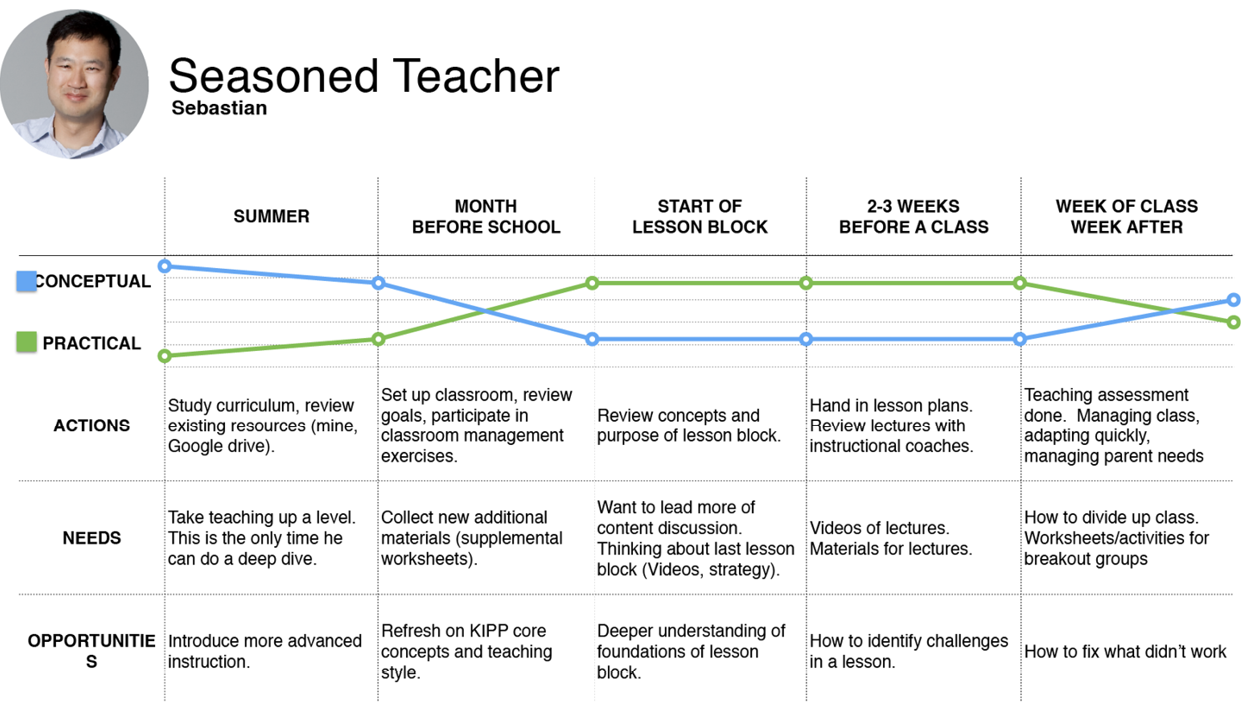

Case Study: Teacher Timeline

Challenge: We looked at a group of teachers and what they sought at different times of the year in terms of continuing education and support from experts that could improve their teaching skills and strategies. We learned that depending on the time of year, the support these teachers wanted was drastically different (Figure 13-2).

Figure 13-2

Journey map representing a teacher’s focus and interests throughout an academic year

Outcome: In the summer, teachers had more time to digest concepts and foundational research concerning the philosophy of education. This was the best time for them to focus on their own development as teachers and consider the why behind their teaching methods. Right before the school year started, however, they went from wanting conceptual development to wanting very pragmatic support. Students would soon be showing up after a three-month break, and teachers would have to manage them—in addition to the parents. During this time, they wanted highly practical information like worksheets. The microdecisions they had to make were things like “Can I print this worksheet out right now?” “Does it have to be printed at all?” or “Can we use it on Chromebooks?” During the school year, they weren’t concerned with the why but the how, often defaulting to satisficing when they became overwhelmed with too much information. Based on these findings, we were able to recommend drastically different types of content at different points of the year.

Chart Me a Course: The Decision-Making Journey

We want to know not just the overall decision our customers are making, like whether to buy a car, but also all the little decisions they have to make along the way. “Does it have cup holders?” “Will my daughter be happy riding in it?” “Can it carry my windsurfer?” “Can I put a roof rack on the top?”

Timing of information is crucial when it comes to these microdecisions. Once we’ve identified the questions, we want to know when the customer need to address each of them. Usually it’s not all at once, but one step at a time along the journey. That’s why most ecommerce sites place shipment information at the end, for example, rather than presenting you with too much information right at the start, when you’re just browsing.

We also want to know what our users think they can do to interact with the system and solve their problem. In cognitive neuroscience, we talk about “operators in a problem space,” which just means the levers that we think we can move in our heads to get from where we are to where we need to be. The actual problem space may be the same as or different than what your customers are envisaging, depending on how expert they are in the subject matter.

Real-World Examples

Looking once again at the sticky notes. Here are some findings that relate to decision making (Figures 13-3 through 13-7):

“Concern: ‘What if the $5,000 chair I’m buying is damaged in transit?’”

This person is basically saying they’re not going to go any further with the purchase until they understand the answer to this shipping and handling question. You could argue there’s some emotional content of worry or fear here, but I would say the most important aspect is that it’s one of several problems to be solved along this user’s decision-making journey. This will be a blocker and needs to be resolved to the customer’s satisfaction before they hit the “buy” button.

Figure 13-3

Research observation: a reason customers might not hit “buy”

“Surprised that coupons can’t be entered on the product page to update price.”

I see this type of comment a lot in ecommerce (we’ll take a look at a case study momentarily). In physical shopping interactions, we typically hand the cashier our coupons before we pay. When ecommerce sites order the interaction differently, it can throw us off and make it difficult for us to proceed without assurance that our coupon will count. Suddenly we have no interest in buying for full price!

Figure 13-4

Research observation: the importance of matching expected shopping flow

“Wants to know right away if this site will accept PayPal.”

Here’s another microdecision example of something the user wants to know before proceeding any further. A lot of people have a preferred or trusted method of payment, so even though we tend to put payment information toward the end, this feedback suggests that we need some indicator early on alerting the customer to the modes of payment we accept. This is another microconsideration the customer needs to tick off before they’re willing to keep going.

Figure 13-5

Research observation: a microdecision to be made before purchasing

“Wants easy way to buy on laptop and send movie to TV.”

This is a good example of classic problem solving, representing how the user wants to solve a problem and move around in the problem space. The problem is how to use a different tool to do the buying (of a movie) than to do the viewing. There’s a bit of interaction design going on here, but I’d argue that the highest-level issue in this case is solving a problem.

Figure 13-6

Research observation: a concrete problem the customer is trying to solve

“Doesn’t want parents to know what she’s watching.”

This customer is wondering about privacy settings at this stage of her decision-making process. Maybe she wants to make sure her parents don’t know she’s watching horror movies before she commits to this service. Privacy considerations like what’s being recorded and logged, levels of privacy, and who’s receiving that data are all very legitimate concerns in our Big Data world right now.

Figure 13-7

Research observation: a secondary problem that is also important to the customer

Case study: Coupons

Challenge: We worked with one group that offered language classes, which people could buy online. This group offered coupons, but the programmers placed the coupon code feature at the tail end of the purchasing process (it was easier to program that way). So someone buying a three hundred dollar course with a one-third-off coupon would have to first check a box indicating that they wanted to buy the course at full price, then put in the coupon, and then finally see the price drop to two hundred dollars. Most people would feel uncomfortable selecting the full-price course and hitting “go” without seeing confirmation that their coupon code had gone through.

Recommendation: We strongly advised the group to move the coupon code feature up in the process, so that users were checking a box that showed their applied discount. There’s actually a lot of psychology behind “couponing,” but I’ll save that for another book.

Concrete Recommendations

- Periodically ask what users are trying to do at that moment and map out the microgoals that together suggest the expected path to the end answer (e.g., enter zip code, select movie, select date, view and select a location, view and select seats, reserve those seats).

- Build a decision-making journey map—why they are looking for information, what information they want or don’t want at that step, and what they need next.