[ 9 ]

Vision: Are You Looking at Me?

Now that we’ve discussed how to conduct contextual interviews and observe people as they’re interacting with a product or service, I want you to think about how those interviews can provide important clues for each of the Six Minds.

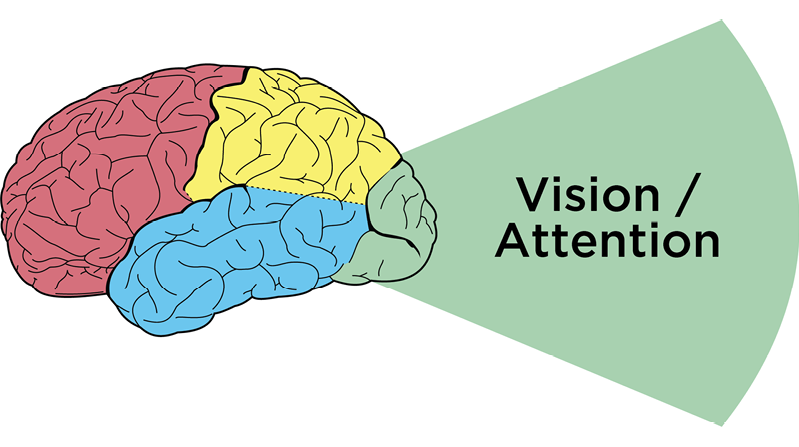

I’d like to start by looking at this from a vision/attention perspective (Figure 9-1). In considering vision, we’re seeking to answer these questions about their customers:

- Where are their eyes looking? (Where did they focus? What drew their attention? What does that tell us about what they were seeking, and why?)

- Did they find what they were looking for? If not, why? What were the challenges in them finding it?

- What are the ways that new designs might draw their attention to what they’re seeking?

We’ll discuss not only where customers look and what they expect to see when they look there, but also what this data suggests about what is visually salient to them. We’ll consider whether users are finding what they are hoping to find, what their frame of reference is, and what their goals might be.

Figure 9-1

Vision and visual attention in the Occipital cortex

Where Are Their Eyes? Eye-Tracking Can Tell You Some Things, But Not Everything

When it comes to improving interfaces or services, we start with where participants are actually looking. If we’re talking about an interface, where are users looking on the screen? Or where are they looking within an app?

Eye tracking devices and digital heat maps come in handy for this type of analysis, helping us see where our users are looking. This sort of analysis can help us adjust the placement of our content on a page.

But you don’t always need eye-tracking if you use good old-fashioned observation methods like those we discussed in the previous chapter. When I’m conducting a contextual interview, I try to set myself up at 90 degrees to the participant (so that I’m a little bit behind them without creeping them out, as seen in Figure 9-2). There are a few reasons for this:

- It’s a little awkward for them to look over and talk to me. This means that they are primarily looking at the screen or whatever they’re doing, and not me (allowing me to better see what it is they’re working on, clicking on, etc.).

- I can see what they’re looking at. Not one hundred percent, of course, but generally, I’m able to see if they’re looking at the top or bottom of the screen, or down at a piece of paper, flipping through a binder to a particular page, etc.

Figure 9-2

Moderating a contextual interview

Speaking of where people’s eyes are, take a look at Figure 9-3. This figure shows two screens side by side from an electronics company—blurred out a bit, with the color toned down. This is the type of representation your visual system uses to determine where to look next.

Figure 9-3

What your visual attention system sees when you look at an image

In the image on the left there are four watches, with two buttons below each watch. Though you can tell at a glance that these are buttons, it’s not clear from the visual features and this level of representation which is the “buy” button and which is the “save for later” button. The latter should appear as a secondary button, yet it currently draws an equal amount of attention as the “buy” button. That’s something we would work with a graphic designer to adjust.

In the image on the right, the buttons don’t have sufficient visual contrast to draw attention to them, and simply blend into the background, making them easily overlooked.

Case Study: Security Department

Challenge: Even though many of my examples are of digital interfaces, we as designers also need to be thinking about attention more broadly. In this case, I worked with a group of people with an enormous responsibility: monitoring security for a football stadium–sized organization (and/or an actual stadium).

Their attention was divided in so many ways. Here are all the systems and tools (along with their respective alerts, bells, and beeping sounds) they monitored at any given time:

- Literally hundreds of cameras, with the number increasing all the time

- Special cameras focused on problem areas (e.g., the door people frequently used to sneak in the back)

- Walkie-talkies with updates from foot patrols

- Emails

- Texts

- The local police radio (with constant communication)

- Card-swipe systems for badge-controlled doors (which beeped many times a minute)

- Broadcast PA systems

- CNN

- Fire alarms

- Elevator alarms

- Electrical alarms

- Phone banks

If you’re impressed that anyone could get work done in such a busy environment, you’re not alone; I was shocked (and a bit skeptical about whether all these noisy systems were helping rather than hurting their productivity). Here was an amazing challenge of divided attention, far more distracting than an open office layout (which many people find distracting).

Recommendation: With huge visual and auditory distractions in play, we had to distill the most important thing that staff should be attending to at each moment. My team developed a system very similar to a scroll-based Facebook news feed, except with extreme filtering to ensure the relevancy of the feed (no cat memes here!). Each potential concern (terror, fire, door jams, etc.) had its own chain of action items associated with it, and staff could filter each issue by location. The system also included a prominent list of top priorities—at that moment—to help tame the beastly number of items competing for attention. It had one scroll and could be set to focus on a single topic or all topics, but only when the topics rose to a specific level of importance. As a result, staff knew where to look and what the (distinct) sound of an alert sounded like.

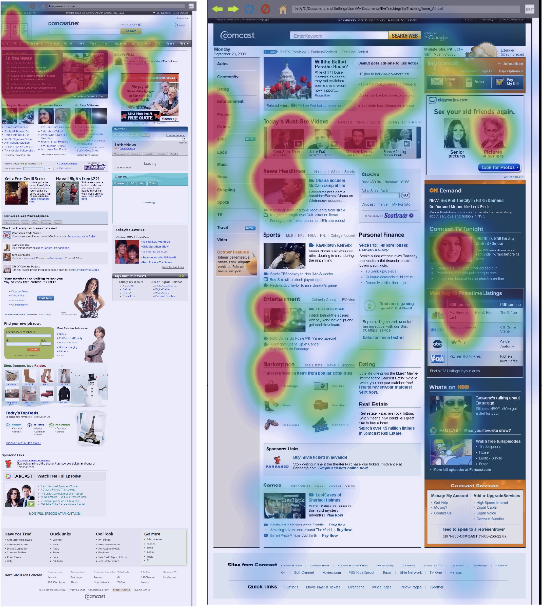

Quick, Get a Heat Map…

Eye gaze heat maps show us where our users’ eyes are looking on an interface. We can get a representation of the total time people spend looking at different parts of the screen; areas they focus on for longer appear to be “hotter” in other locations (Figure 9-4).

Figure 9-4

Heat maps

Case Study: Website Hierarchy

Challenge: In the case of the site pictured in Figure 9-4 (Comcast.net, the precursor to Xfinity) in the original version (on the left), consumers were overwhelmingly looking at one area in the upper-left corner, but not further down the page, nor at the right side of the page. We knew this both from eye tracking and the fact that the partner links further down the page weren’t getting clicks (which the partners were not happy about). The problem was the visual contrast. The upper-left corner of the old page was visually much darker than the rest of the page, and more interesting (videos, images)—so much so that it was overwhelming people’s visual attention systems.

Recommendation: We redesigned the page to make sure that the natural visual flow included not only the headlines, but the other information down below. We gave more visual prominence to the neglected sections of the page through balancing features like visual contrast, size of pictures, colors, fonts, and white space. We were able to draw people down visually to engage “below the fold.” This made a huge difference in where people looked on the page, making end users, Comcast, and its paid advertising partners much happier.

This case study shows how helpful tools like eye tracking and heat maps can be. But I want to counter the misperception that these tools on their own are enough for you to make meaningful adjustments to your product. Similar to the survey results and usability testing that I mentioned in the last chapter, heat maps can provide you with a lot of the what, but not the why behind a person’s vision and attention. The results from heat maps do not tell you what problem users are trying to solve.

To get at that, we need to…

Go with the Flow

We’re trying to satisfy customers’ needs as they arise, so we want to know at each stage in problem solving what our users are looking for, what they’re expecting to find, and what they’re hoping to get as a result. Then we can match the flow with what they’re expecting to find at each stage of the process.

While observing someone interacting with a site, I’ll often ask them questions like “What problem are you trying to solve?” and “What are you seeing right now?” This helps me see what’s most interesting to them, at this moment, and understand their goals.

There are many unspoken strategies and expectations that users employ, which is why we can only learn through observing users in their natural flow. These insights, in turn, help us with our visual design, layout, and information architecture by clarifying what the steps are, how they should be represented, where they should be in space, etc.

Case Study: Auction Website

Challenge: Here’s an example of some of those unspoken expectations that we might observe during contextual interviews. In testing the target audience for a government auction site, I heard the feedback “Why doesn’t this work like eBay?” Even though this site was even larger than eBay, our audience were much more familiar with eBay, and brought their experience and related expectations regarding how eBay worked to their interactions with this new interface.

Eye tracking confirmed users’ expectations and confusion: they were staring at a blank space beneath an item’s picture and expecting a “bid” button to appear, since that’s where the “bid” button appears on eBay items. Even though the “bid” button was in fact present in another place, users didn’t see it because they expected it to be in the same location as on eBay.

Recommendation: This was one case where I had to encourage my client not to “think different,” but rather admit that other systems like eBay have cemented users’ expectations about where things should be in space. We switched the placement of the button (and a few other aspects of the site architecture) to match people’s expectations, which immediately improved performance. We knew where they were looking for this particular feature, and we knew they didn’t find it in that location. This wasn’t because of language or the visual design, but because of their experience with other similar sites and associated expectations.

Real-World Examples

I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to put my Post-it note categorization method into practice yet, but I’d like to share some examples of the findings I noted in the previous chapter from clients interacting with both a video-streaming website and an e-commerce website (Figures 9-5 through 9-8). These will give you a sense of what we’re looking for when subdividing data according to the Six Minds; in this case, focusing on vision and attention. Remember, there’s often overlap, but I’m most concerned with the biggest problem underlying each comment:

“Can’t find the ‘save for later’ feature.”

In this case, the user was looking for a certain feature on the screen and couldn’t find it, implying a visual challenge. In processing this feedback, we want to consider if a “save for later” feature was indeed present, and if so, why this participant was unable to find it. If the feature was there but was named something else (e.g., “keep” or “store for later”), this would be a language issue. Before making any changes, we would want to know if other participants had a similar issue. However, if the feature was indeed present, yet the customer’s attention was not attracted to it, then yes indeed, this would be a vision/attention issue. Just note that some comments related to “finding” in a visual scene are not necessarily visual issues (e.g., they might signify language or other issues).

Figure 9-5

Research observation: participant unable to find a “Save” feature

“Homepage busy and intimidating. ‘This is a lot!’”

This sounds like it is related to vision and attention. We should review the organization of this page and its information density.

Figure 9-6

Research observation: participant notes the homepage’s visual complexity

“Viewed results but didn’t see ‘La La Land’”

It sounds like the user missed something on the page. In this example, we know the movie La La Land appeared in the search results, but it didn’t pop out to the user. For some reason, the visual features of the search results (think back to the examples of visual “popout” that we looked at in Chapter 2, like shape, size, orientation, etc.) weren’t as captivating as they should have been. Perhaps there wasn’t enough visual contrast between the different search results, or there wasn’t an image to draw the user’s attention. Or maybe the page was just too distracting. You can take this type of feedback straight back to your visual designer. The video of this situation might be especially valuable to indicate what improvements might be made.

Figure 9-7

Research observation: participant failed to notice results on the page

“Didn’t notice ‘Return to results’ link. Looking for a ‘back’ button.”

Here’s a great example of the types of nuance we need to pay attention to. When you read “didn’t notice,” you might automatically assume this is about vision. But don’t be fooled—there could be a language component at issue as well. To determine which it is (vision or language), you would need to do some sleuthing using your observational data and/or eye tracking to see where the user was looking at this moment. If they were staring right at the “return to results” link and it was still not working for them, then you know it’s a language problem—those words didn’t trigger the semantic content they were looking for (i.e., wrong words).

Once you’ve reviewed all of your customers’ feedback and distilled the major problem to address, you can provide this to the visual design team with quite specific input and recommendations for improvement.

Figure 9-8

Research observation: participant failed to see button, looking for a different term

Concrete Recommendations

- Sit perpendicular to the participant—watch where they are looking on screens and interfaces for the next steps.

- Determine what they are looking for and why (what is most relevant to this participant at this moment, and what do they think will be good about finding that?).

- What are the assumptions they have about the system that justify those anticipations (e.g., “I’m looking for the menu because I want to make this word bold, but I don’t see any menu up here; I just see all the words”)?

- What else does their pattern of interaction suggest about their assumptions and unspoken strategies concerning this system?

- Build a mental model of the participant’s thought process, from their perspective, watching their eye movements and behavior.