[ 15 ]

Sense-Making

In Part II, we collected data from contextual inquiry interviews and sorted it into our Six Minds framework. Now we can move onto our next major goals:

- Looking for commonalities among dimensions of the Six Minds (level of expertise, feelings of anxiety, etc.)

- Segmenting customers by their needs (e.g., novices versus experienced professionals, supervisors versus analysts, parents versus children) and relevant dimensions (e.g., word usage, microgoals, underlying assumptions), and building a psychographic profile of each segment

Finally, we’ll end this chapter with a few notes about another system of classification (See/Feel/Say/Do) and why I believe it fails to organize the data in a way that is truly helpful for product and service design.

Affinities and Psychographic Profiles

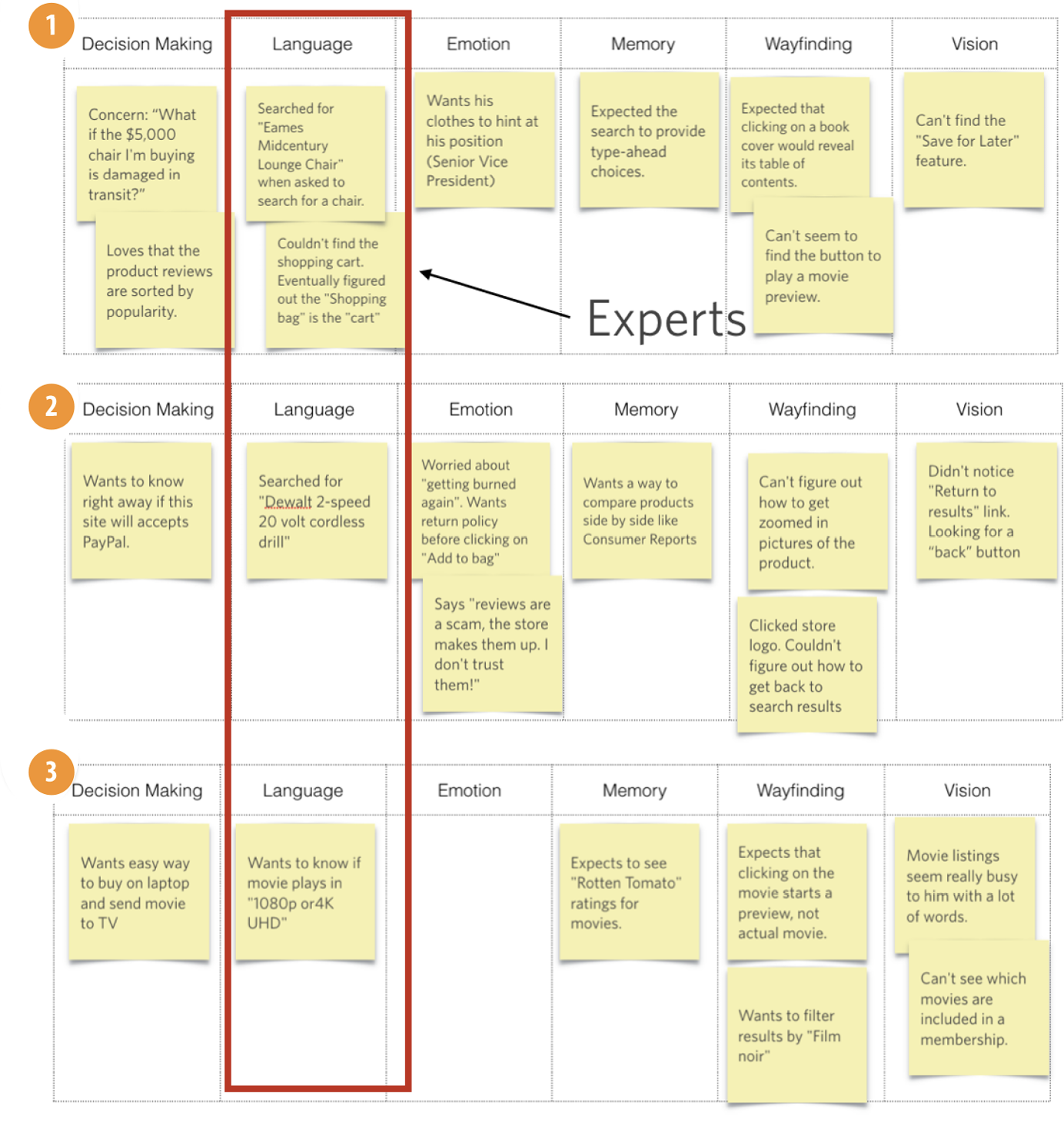

Using our Six Minds framework, let’s review the findings for our example participants from Part II. We have all our sticky notes grouped by participant and by the Six Minds. Now it’s time to look at these findings and see if there are any relationships between them or any underlying similarities in how these individuals are thinking (Figure 15-1).

Figure 15-1

Findings from contextual interviews, organized by the Six Minds

Language

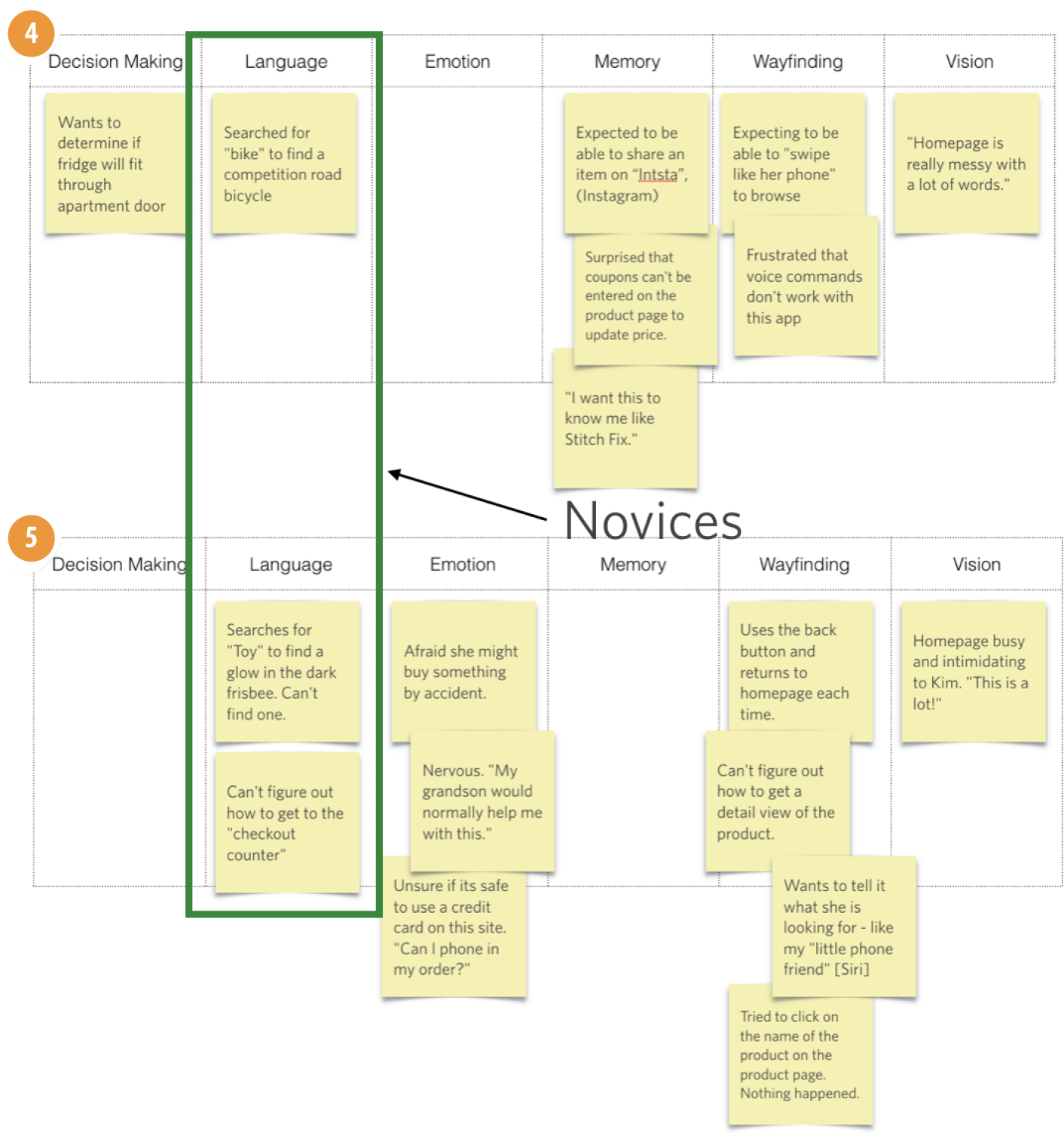

Looking at the column for Language, I see that Participants 1, 2, and 3 are all using terms like “Eames Midcentury Lounge Chair,” or “DeWalt 2-speed, 20-volt cordless drill,” or “1080p or 4K UHD” (Figure 15-2). While they’re searching for very different things, these three participants all have pretty sophisticated language for what they’re talking about. They seem to be experts, if not professionals, in their particular fields, and are very knowledgeable in the subject matter.

Figure 15-2

Reviewing the commonalities between participants within the Language section of the Six Minds

In contrast, it looks like Participant 4 searched for a “bike” while looking for a competition road bike. Participant 5 searched for a glow-in-the-dark Frisbee by typing in “toy.” Participant 5 also talked about getting to the “checkout counter,” rather than “Amazon checkout” or “QuickPay,” or something else that would suggest more knowledge of how the online shopping experience works.

Just by looking at the language, we can see that we’ve got some people with expertise in the field, and others who are much more novices in the area of ecommerce. Moving forward, it might make sense to examine how the experts approach aspects of the interface, versus how the novices approach those same aspects, and see if there are similarities across those individuals.

This is just a start, though. We don’t want to pigeonhole anyone into just one category, because ultimately we are trying to find commonalities on many dimensions. Using a different dimension or “mind,” we could look at these same participants in a very different way.

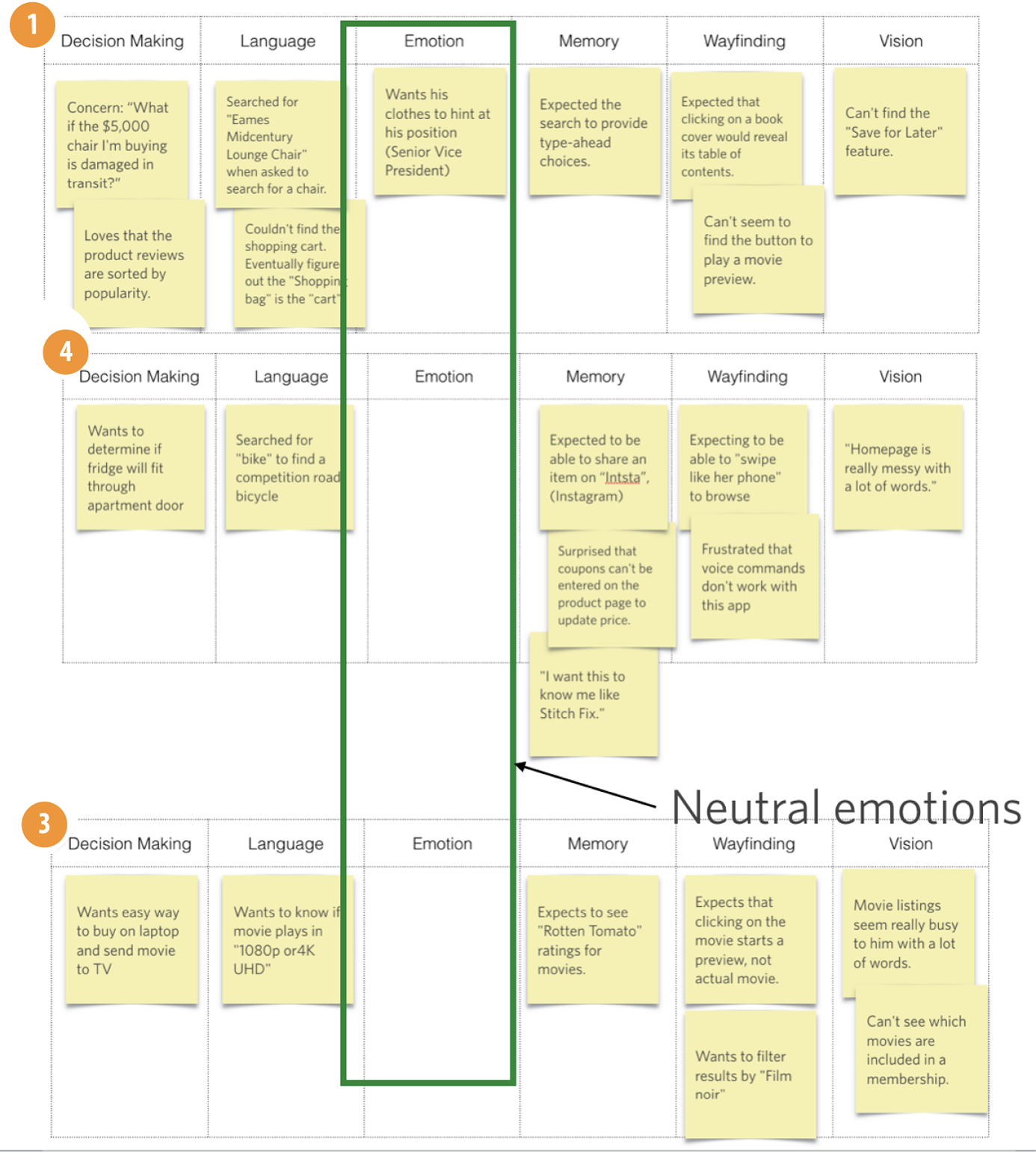

Let’s take emotion (Figure 15-3). Looking across all the findings, we see that Participants 2 and 5 both seemed pretty concerned about the situation, and were afraid that something bad might happen or that they would “get burned again.” We’re definitely seeing some uncertainty and reticence to go ahead and take the next step because they’re worried about what might happen. These folks might need some reassurance. Participants 1, 3, and 4, on the other hand, aren’t displaying any of that emotion or hesitation.

Could there be other areas in which Participants 2 and 5 are also on the same page? Maybe there are similarities in how they do wayfinding, or the information they’re looking for, as opposed to Participants 1, 3, and 4, who seem to be going through this process in a more matter-of-fact way.

Emotion

Figure 15-3

Reviewing the commonalities between participants within the Emotion section of the Six Minds

Using different dimensions, we can look at people and see how we might group them. Ideally, we would hope to find similarities across multiple dimensions. I’m using a tiny sample size for the sake of illustration in this book, but typically, we would be looking at this with a much broader set of data—perhaps 24 to 40 people—anticipating groups of 4 to 10 people, depending on how the segments fall out.

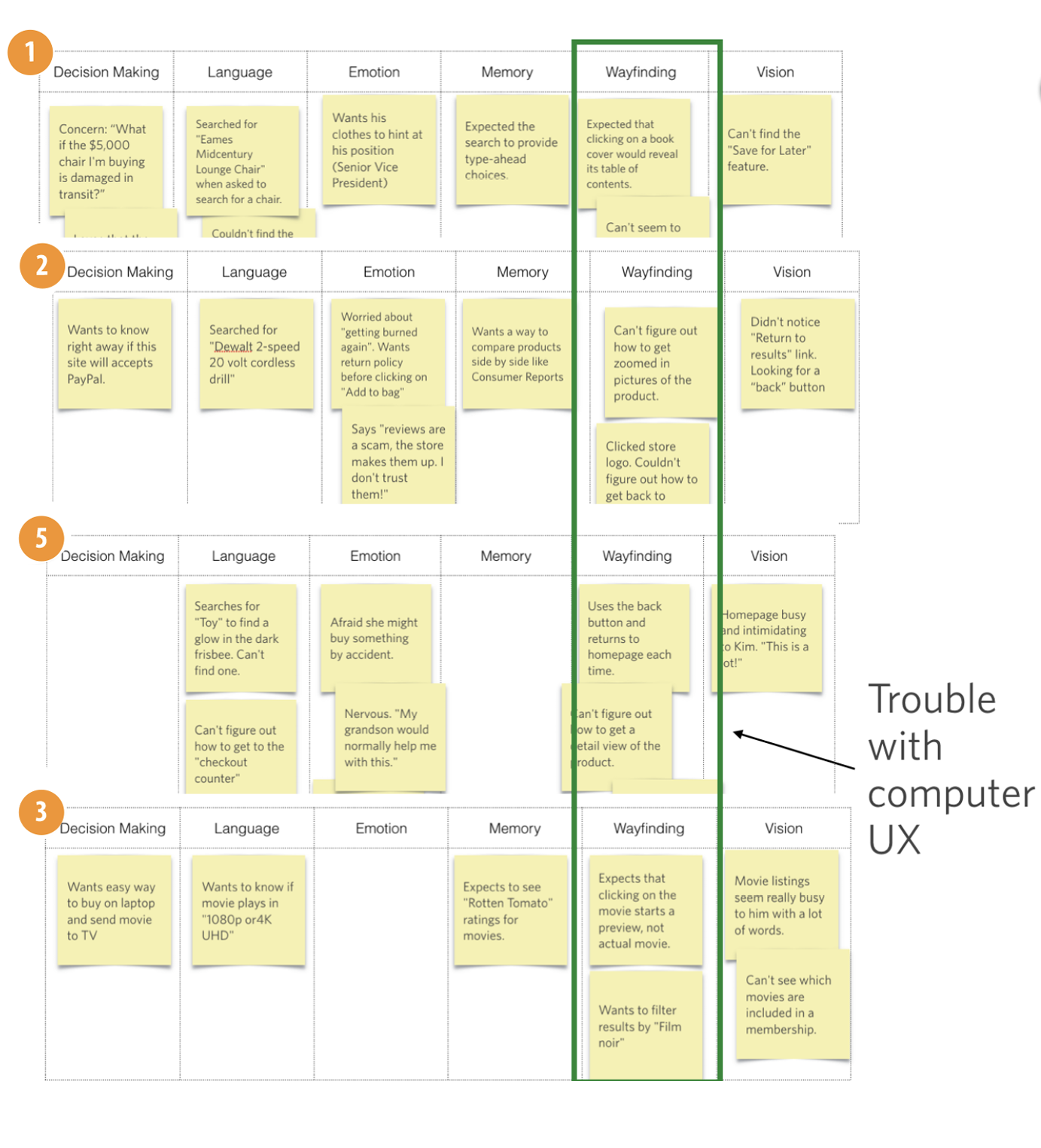

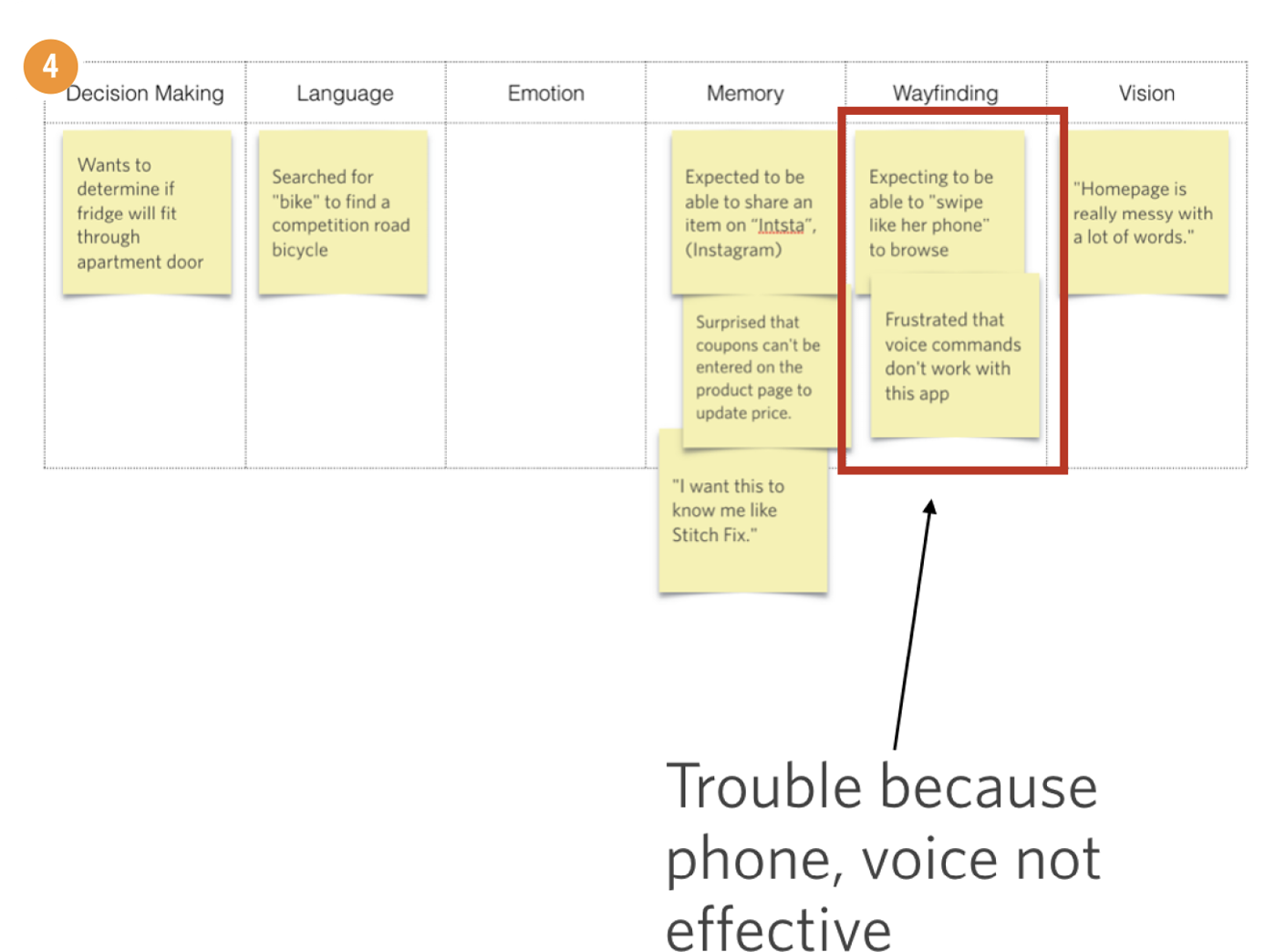

Wayfinding

When we look at wayfinding we see that Participants 1, 2, 3, and 5 all had problems with the user experience or the way that they interacted with a laptop (Figure 15-4). Participant 4 approached the experience very differently, expressing a desire to be able to “swipe like her phone” or use voice commands. This participant seems far more familiar with the technology, to the extent that she has surpassed it and is ready to take it to the next level. Through the Wayfinding lens, we see that our participants are looking at the same interface using varied tools and with varied expectations in terms of their level of interaction design and sophistication.

Figure 15-4

Reviewing the commonalities between participants within the Wayfinding section of the Six Minds

We’ve seen three ways we could group this batch of users, and there are others. Which one does it make the most sense to pick? Sometimes—actually, it’s pretty common—it might be really obvious to you that certain people are of one accord and can be grouped together. Other times, you may see some commonalities among a subgroup, but there’s no real equivalent from the others.

Finding the Dimensions

The best way to illustrate the audience segmentation process is through real-life examples. With the case studies that follow, I’ll show you just one grouping per data set, to give you a taste of the kinds of groupings you might produce.

Case Study: Millennial Money

When working with a worldwide online payments system (you’ve heard of it), my team and I performed contextual interviews with Millennials, trying to understand how they use and manage money and how they define financial success.

The sticky notes in Figure 15-5 represent real-life findings from people we met with. Once again, the question is: “How would I organize these folks?” This picture shows all the notes sorted by person for a handful of the participants.

Figure 15-5

Participants displayed with relevant data in each vertical

One subset of the participants shared the commonality of a life focused on adventure. Their desired lifestyle dramatically affected their decision making about money—after saving just enough, they would immediately use that money for their latest Instagram-ready adventure. We saw that what made these participants happy, and their deepest goal (emotion), was to have new experiences and adventures. They were putting all their time and money into adventures and travel. Ultimately, what was really meaningful to them at that deep emotional level was experiences, rather than things.

Another observation that falls within the category of emotion is that the participants weren’t really defining themselves by their job or other traditional definitions (e.g., “I’m an introvert”); instead, they seemed to find their identity in the experiences they wanted to have.

Socially speaking, these people were instigators, and tried to get others to join them in their adventures. New possibilities, and offers of cheap tickets for which they knew the ticket codes (language), easily attracted their attention (attention!). They were masters of manipulating social networks (Instagram, Pinterest) to share and learn about new places (wayfinding, perhaps both in our sense of wayfinding—the ability to navigate apps like Instagram—and physical wayfinding to find these new places!).

Using the Six Minds framework, I think we saw several things in these participants (remember, this was on behalf of that big online payments system, so we were particularly interested in groupings related to how participants managed their money):

Decision Making

They weighed every money-related decision against their goal of having new experiences. Their level of commitment to long-term financial planning was nonexistent because they were focused on living in the moment.

Emotion

Maximizing their adventure-readiness was paramount, and anything that got in the way of that happiness was seen as negative. Conversely, any payment system that helped them achieve their far-flung lifestyle was a plus.

Language

They had amazing vocabulary and knowledge of travel sites and airline specials—even the codes for airfares (did you know airfares have codes?). They spoke the lingo of frequent flyer miles, baggage fees, and rental cars because they were experts in travel.

We looked at other audiences for that study, but I just wanted to give you a feeling for a real grouping and how in this case we mostly used decision making, emotion, and a bit of language as the key drivers for how we organized participants. Other dimensions, like the way that they interacted with apps (wayfinding) or their underlying experiences and the metaphors they used (memory), just weren’t as important as the central concept of adventure that they organized their lives around.

This is pretty common. With audience segmentation, higher-order dimensions, like decision making and emotion, tend to stand out more than the other Six Minds dimensions. If your study is focused on an interface-intensive design situation, like designers working on the program Adobe Photoshop, for example, you might find groupings that have more to do with vision or wayfinding.

Case Study: Trust in Credit

The second example I want to share concerns a study we did on behalf of a top 10 financial company. We studied how much people know about their credit scores and how they’re affected by them. We also wanted to gauge people’s overall knowledge about credit and fraud.

We cound several types of groups, but I’m only going to describe one persona here: the Fearful & Unsure group. For them, financial transactions were tied much more to emotion than is typical of the

average individual. One woman who we’ll call Ruth was incredibly embarrassed when her credit card was denied at the grocery store because someone had actually stolen her identity. This led to feelings of anxiety, denial, powerlessness, fear, and being overwhelmed.

In this audience segment, people like Ruth just hid from the issue (Emotion). Unlike other people who were inspired to take action and learn about credit to protect themselves, members of this Fearful & Unsure segment were too shell-shocked to take much action (Decision Making). They tried to avoid situations the problem could occur again, and were operating in a timid defense mode, rather than offense (Attention). This Fearful & Unsure group didn’t consider themselves credit-savvy, which was consistent with the way they spoke about credit issues (Language).

What’s driving this psychographic profile is the individuals’ emotional response to a situation involving credit, resulting in a unique pattern of decision making, the language of a novice, and an unawareness of ways to reduce their credit risk in the future.

Challenging Internal Assumptions

In the examples we just reviewed, I used more complex cognitive processes like decision making, emotion, and language to segment audiences across an industry or target audience pool. In many cases, you might have a boss or a manager who’s used to doing audience segmentation in a different way (e.g., “We need people who are in these age ranges, spend this much, are in these socio-economic brackets, or have these titles”). I want you to be ready to challenge some of these assumptions.

If your analysis seems to contradict some of the big patterns from yesteryear, be prepared to receive some pushback. Don’t be afraid to say, “No, our data is actually inconsistent with that”—and point to the data! Go ahead and test the old assumptions to see if they’re still valid.

When possible, try to get a sample that’s at least 24 people. If you can get a geographically dispersed or even linguistically diverse sample, so much the better. All of these considerations are ammunition to help you answer the question, “Was this an unusual sample?” When you have a large, diverse sample, you can say, “No; this is well beyond one or two people who happen to think in this way.”

At times, you’ll need to challenge not only the outdated notions of colleagues, but also your own preconceptions. Sometimes the data we find challenges our own ideas and ways of organizing material. In these cases, I urge you to make sure that you’re representing the data accurately, and not viewing it through the lens of presupposition.

Back in Chapter 7, I challenged you to approach contextual inquiry with a “tabula rasa” (clean slate) mentality. Leave your assumptions at the door and be open to whatever the data says. The same goes for audience segmentation. As best you can, try not to approach the data with your own hypotheses. We know statistically that people who say “I know that X is true” are looking for confirmation of X in the data, as opposed to people who are just testing out different possibilities. Be the latter type of analyst. Be open to different possibilities.

Always try to negate the other possibilities, as opposed to only looking for information that confirms your hypothesis. Look carefully at the underlying emotional drivers for each person. How are they moving around their problem space, and what are they finding out? What are the past experiences that are affecting them, and do the segments hinge on those past experiences?

In the case of the small business owners mentioned in Chapter 12, we went back and forth a lot on what the salient features were for audience segmentation. There was the fact that they problem-solved from two very different perspectives. There was the language and sophistication level factor, which also differed greatly based on the subject matter (e.g., craft expertise versus business expertise). There were several patterns we were seeing. To land on our eventual segmentations, we had to test each of these patterns across our audience segmentations and make sure those patterns were really borne out across the data.

Finally, when possible, try to organize your participants by the highest-level dimension possible. Even though you may start out with surface-level observations, try to go deeper to get at those drivers and the underlying goals. As a psychologist, I give you permission to dig deeper into the psyche—into the big, bold emotional state that influences the way people make decisions.

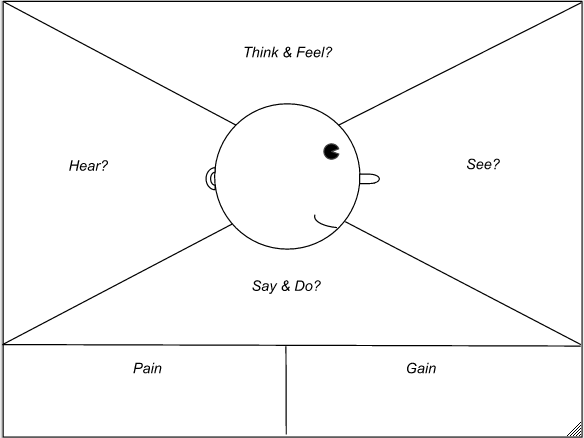

Ending an Outdated Practice: See/Feel/Say/Do

If you are familiar with empathy research, you may have heard of the See/Feel/Say/Do chart (Figure 15-6). These charts are popular with many groups looking for a mechanism to develop empathy for a user. They may also be used to help to segment customers into groupings.

Figure 15-6

Customer empathy map

A lot of empathy research programs use a diagram like this one. See/Feel/Say/Do diagrams ask the following questions of your customers:

- “What are they seeing?”

- “What are they feeling and thinking?”

- “What are they saying and doing?”

- “What are they hearing?” (some diagrams leave this one out)

The diagram shown here also includes a Pain/Gain component, asking “What are some of the things your user is having trouble with?” (pain) and “What are some opportunities to improve those components?” (gain).

To some folks, this looks a lot like the Six Minds. What’s the difference? Let’s look more closely at how they align:

See

At first glance, this is pretty clearly tied to vision. But remember: when we consider what the user is seeing, we want to know what they’re actually looking at or attending to—not necessarily what we’re presenting to them, which may be different. I want to make sure that we’re thinking from an audience perspective, and taking into account actually what they’re really seeing. There is an important component that is missing here: What are they not seeing? We want to know what they are searching for, and why. It is crucial to consider the attentional component, too.

Feel

It may seem like this would be synonymous with emotion—think again. In these empathy diagrams, “Feel” is talking about the immediate emotion of a user in relation to a particular interface. The questions is, “What is the user experiencing at this very moment?” As you may remember from our discussion of emotion, from a design perspective, we should be more interested in the deeper, underlying sources of emotion. What is it that your users are trying to achieve? Why? Are they fearful of what might happen if they’re not able to achieve that? What are some of their deepest concerns? In other words, we want to push beyond the surface level of immediate reactions to an interface and consider the more fundamental concerns that may be driving those reactions.

Say

Often, saying and doing are grouped together, but first let’s focus on the saying. I struggle with the notion of just reporting what users are actually saying, because at the end of the day, they can say things that relate to any of the Six Minds. They might say what they’re trying to accomplish, which would be decision making. They could describe how they’re interacting with something, which would be wayfinding. Or maybe they’re saying something about emotion. If you recall the types of observations we grouped under Language in Part II with our sticky note exercise, they weren’t a mere litany of all the things our users uttered; we identified all the things our users said (or did) that pertained to the words being used in a certain interface. I believe that language has to do with the user’s level of sophistication and the terms they expect to see when interacting with a product.

By categorizing all of the words coming out of our users’ mouths as “Say,” I worry that we’re oversimplifying things and missing what those statements are getting at. I also think we miss the chance to determine people’s overall expertise level based on the kinds of words they’re using. This grouping doesn’t lend itself to an organization that can influence product or service design.

Do

When we think about wayfinding, that has to do with how people are getting around in the interface or using the service. We’re asking questions like, “Where are you in the process?” and “How can you get to the next step?” I think wayfinding gets at what the user is actually doing, as well as what they believe they can do, based on their perception of how this works. Just describing behavior (“Do”) is helpful, but not sufficient.

Decision Making (missing)

While “Do” comes close, I think that we’re missing decision making in See/Feel/Say/Do. This style of representation doesn’t mention how users are trying to solve their problem. With decision making or problem solving, we want to consider how our users think they can solve the problem and what operators they think they can use to move around their decision space.

Memory (missing)

Memory also gets short shrift in the See/Feel/Say/Do model. We want to know the metaphors people are using to solve their problem, and the expected interaction styles they’re bringing into this new experience. We want to know about their past experiences and expectations, including those that users might not even be aware of, but that they imply through their actions and words (like how they expect the experience of buying a book to work based on how Amazon works, or how they expect a sit-down restaurant to have waiters and white tablecloths). See/Feel/Say/Do charts leave out the memories and frameworks users are employing.

Hopefully you can see that while it’s better than nothing, See/Feel/Say/Do is missing key elements that we need to consider, and that it also oversimplifies some of the pieces it does consider. We can do better with our Six Minds.