Dialogue

Overview

Animation has enjoyed a long history of uniquely talented voices infusing personality into their respective characters. One of the earliest known voice artists was Disney himself, serving as the voice of Mickey in Steamboat Willie (1928). Artists like Mel Blanc, Daws Butler, and Don Messick devoted their lives to creating the iconic world of talking animals, whereas, Jack Mercer, Mae Questel, and June Foray helped establish the caricature style of voicing humans. As was the case for most voice actors, the characters they voiced would achieve incredible star status yet the public rarely knew the real face behind the voice. Voice actors like Alan Reed (Fred Flintstone) and Nancy Cartwright (Bart Simpson) remain relatively anonymous yet their characters are immediately recognizable throughout the world. The success of features such as American Tail (1986) and The Little Mermaid (1989) helped usher in a renaissance of animation. During this period, the reputation for animation improved and “A” list actors once again began showing an interest in animation projects. Perhaps the recent success of directors Seth MacFarlane and Brad Bird voicing characters for their films suggests that we are coming full circle. Like Disney, they demonstrate that understanding the character is essential to finding and expressing a persona through voice. To learn more about the voice actors behind animation, log onto www.voicechasers.org.

Wait a minute . . . if I’m not talking, I’m not in the movie . . . .

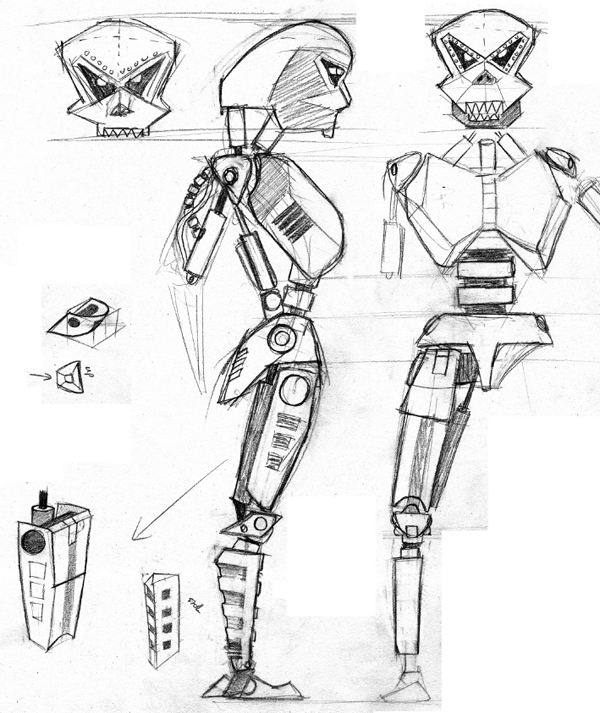

Figure 3.1 Elements of the Dialogue Stem

Principal Dialogue

Dialogue is the most direct means of delivering the narrative, and whenever present, becomes the primary focus of the soundtrack. The speaking parts performed by the main characters are referred to as principal dialogue. Principal dialogue can be synchronous (lip sync) or a-synchronous such as off-screen lines or thoughts shared through voice-over. Some films deliver principal dialogue in a recitative (blending of speech and music) style. Two examples of this approach can be heard in the 1954 animation The Seapreme Court and the 1993 film The Nightmare Before Christmas. With the rare exception of films like Popeye (1933), principal dialogue is recorded prior to animating (pre-sync). The dialogue recordings are then used to establish timings, provide a reference for head and body movements, and serve as the foundation for lip sync.

Narration

Narration differs from principal dialogue in that the speaker is unseen and cannot be revealed through changes in camera angles. Many animations develop a storybook quality for their projects through the use of narration. Narration is an effective means of introducing the story (prologue), providing back-story, and providing closure (epilogue). The use of narration as an extension of the on-screen character’s thoughts is referred to as first person. This technique is used effectively in Hoodwinked! (2005) to support the Rashomon style of re-telling the plot from multiple perspectives. The third-person narration is told from an observer’s perspective. Boris Karloff exemplifies this approach in the 1966 version of How The Grinch Stole Christmas. When used effectively, audiences will identify with the narrator and feel invited to participate in the story. Even though narration is non-sync, it is still recorded prior to animating and used to establish the timings.

Look, up in the sky, it’s a bird; it’s a plane, it’s Superman.

Group ADR and Walla

If you listen closely to the backgrounds in the restaurant scene in Monsters, Inc. (2001), you will hear a variety of off-screen conversations typical of that environment. These non-sync but recognizable language backgrounds are the product of Group ADR. Group ADR is performed by a small group of actors (usually 6 to 8) in a studio environment. They are recorded in multiple takes that are combined to effectively enlarge the size of the group. Group actors perform each take with subtle differences to add variation and depth to the scene. Examples of group ADR can be heard as early as 1940 in the Fleisher Superman cartoons and later in the 1960s cartoons of Hanna-Barbera. A more recent example can be heard in Finding Nemo (2003) during the scene where a flock of sea gulls chant “mine, mine.” In this scene, the words are clearly discernable and as such, are included in the dialogue stem. While group ADR is intelligible, Walla is non-descript. Walla is often cut from SFX libraries or recorded in realistic environments with actual crowds. It can effectively establish the size and attitude of a crowd. Due to its non-descript nature, Walla is included in the FX stem.

Developing the Script

The script begins to take shape at the storyboard stage where individual lines are incorporated into specific shots. Once the storyboards are sufficiently developed, an animatic (story reel) and recording script are created. At this early stage, scratch dialogue is recorded and cut to the animatic to test each shot. Oftentimes it is fellow animators or amateur voice actors who perform these recordings. In some workflows, professional voice actors are brought in at the onset and allowed to improvise off the basic script. With this approach, it is hoped that each read will be slightly different, providing the director with additional choices in the editing room. Once a shot is approved and the accompanying script is refined, the final dialogue is recorded and edited in preparation for lip sync animation.

Casting Voice Talent

Often when listening to radio programs, we imagine how the radio personalities might appear in person. We develop impressions of their physical traits, age, and ethnicity based entirely on vocal characteristics. When casting voices for animation, we must select voices that will match characters that are yet to be fully realized. We seek vocal performers who can breath life into a character, connect with the audience, and provide models for movement. Voice actors must possess the ability to get into character without the aid of completed animation. Though physical acting is not a primary casting consideration, many productions shoot video of the session to serve as reference for the animation process. It is common practice in feature animation to cast well-known actors from film and television, taking advantage of their established voices. Most independent films lack the resources needed for this approach and must look for more creative means of casting. An initial pool of talent can be identified through local television, radio, and theater. If the budget allows, there are a growing number of online options available for casting and producing voice talent (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Online Voice Talent Services

Though it helped to be physical in front of the microphone . . . in a sense, everything is focused into your voice.

(The Prince of Egypt)

Voice actors are often asked to step outside their natural voices to create a caricature. Mimicry, sweeteners, and regional accents are important tools for developing caricature. Animal speak such as the dog-like vocalizations of Scooby Doo or the whale-like speech in Finding Nemo are but a few examples of this unique approach to dialogue. In Stuart Little (1999), cat hisses are added (sweetened) to Nathan Lane’s dialogue to enhance the character of Snowbell, the family cat. In Aladdin (1992), Robin Williams’ voice morphs from a genie into a sheep while vocalizing the phrase “you baaaaaaaad boy.” Regional accents are often used to develop the ethnicity of a character. In Lady and the Tramp (1955), the Scottish terrier, the English bulldog, and the Siamese cats are all voiced with accents representative of their namesake. Caricature can add a great deal of depth to a character if used respectfully. It can also create a timbral separation between characters that help make them more readily identifiable in a complex scene.

To do is to be.

To be is to do.

Do be do be do.

Scoobie Doobie Doo.

Recording Dialogue

The Recording Script

Animation dialogue begins with a vetted recording script (Figure 3.3). Each line of dialogue is broken out by character and given a number that corresponds to the storyboard. The recording script can be sorted by character to facilitate individual recording sessions. Some directors hold rigidly to the recorded script while others show flexibility to varied degrees. Many of the great lines in animation are a result of embellishment or improvisation of a talented voice actor. Since the script is recorded in pre-animation, there still exists the possibility to alter, replace, or add additional lines. Every variation is recorded and re-auditioned in the process of refining and finalizing the dialogue.

Character 1 (Little Orange Guy)

Line 5

(00:03:54:07-00:04:17:12)

I got a plan you see. I’m gonna make a lot more of these machines only bigger. It will make pictures as big as a wall. And they’ll tell stories and people will come from all around and give us money to watch them . . . heh!

Character 2 (Large Blue Guy)

Line 7

(00:04:18:03-00:04:19:22)

Your mad.

Character 1

Line 21

(00:04:23:01-00:04:24:17)

What . . . what what whatabout . . .

Character 2

Line 22

(00:04:24:23-00:04:38:04)

That is by far the looniest thing I’ve ever heard. Look mate, no one will ever want to watch little moving pictures dancing on the walls . . . all right. Much less give some bloody nitwit money for it.

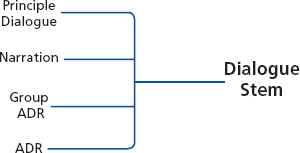

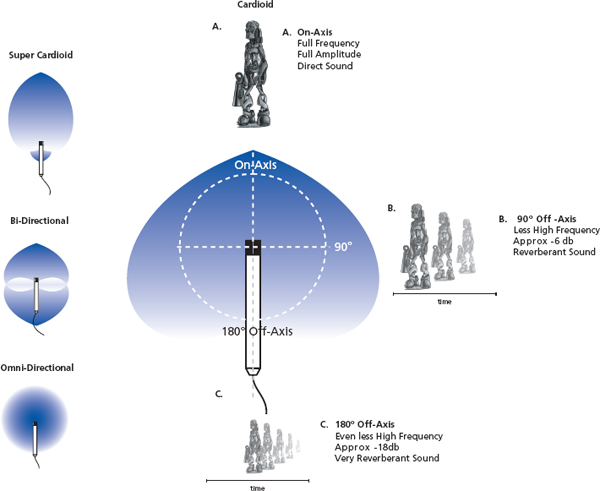

Directing Voice Talent

Actors that are new to the animation process are often surprised to learn that dialogue is recorded without picture. For many, it is the first time they will rely exclusively on their voice acting to deliver a compelling read. Many arrive at the session prepared to deliver a cartoony voice rather than their natural voice. It is the director’s job to help voice actors find the voice best suited for each character. Since their character has not yet been animated, it is important to help the voice actor get inside the character and understand the context for each line. This can be accomplished by providing concept art (Figure 3.4), storyboards, and a brief breakdown of the script. Directors and/or script supervisors often accompany the voice talent in the live room. Their presence should be facilitative and non-threatening. Directors should resist the temptation to micro-manage the session, allowing voice actors flexibility to personalize the script through phrasing, inflection, and non-verbal vocalizations. In some productions, voice actors are encouraged to improvise off-script. The spontaneity and authenticity resulting from this approach can potentially transform a character or a shot. During the session, it is helpful to record in complete passes rather than stopping in mid-phrase to make a correction. By recording through mistakes, we avoid “paralysis through analysis” and the session produces more usable material.

Figure 3.4 Concept Art from the Film Trip to Granny’s (2001) Directed by Aaron Conover

Ok, I’d like to do it again . . .

ALONE!!!—

The ADR Studio

It is not uncommon for dialogue to be recorded in Foley stages or in facilities designed for music production. Recording dialogue in a professional facility offers many advantages including well-designed recording spaces, professional grade equipment, and experienced engineering. Because most dialogue is recorded from a close microphone placement (8 to 12 inches), any good sounding room can be transformed into a working studio. The essential components of an ADR studio include a digital audio workstation, quality microphones, audio and video monitors, and basic acoustic treatments. The recording software must support video playback with time code. It is important to select video monitors and computers that are relatively quiet. Whenever possible, they should be isolated from the microphone or positioned at a distance that minimizes leakage. If the room is reverberant, sound blankets can be hung to provide additional dampening and sound isolation.

Microphones

Microphones are the sonic equivalent of a camera, capturing varied degrees of angle (polarity) and focus (frequency and transient response). Most dialogue mixers prefer large diaphragm condenser microphones as they capture the widest frequency range with the greatest dynamic accuracy. The Neumann U-87 microphone is a popular yet pricey choice (Figure 3.5). There are many condenser microphones that meet high professional standards yet are priced to suit smaller budget productions.

Figure 3.5 Neumann U-87 with Pop-filter

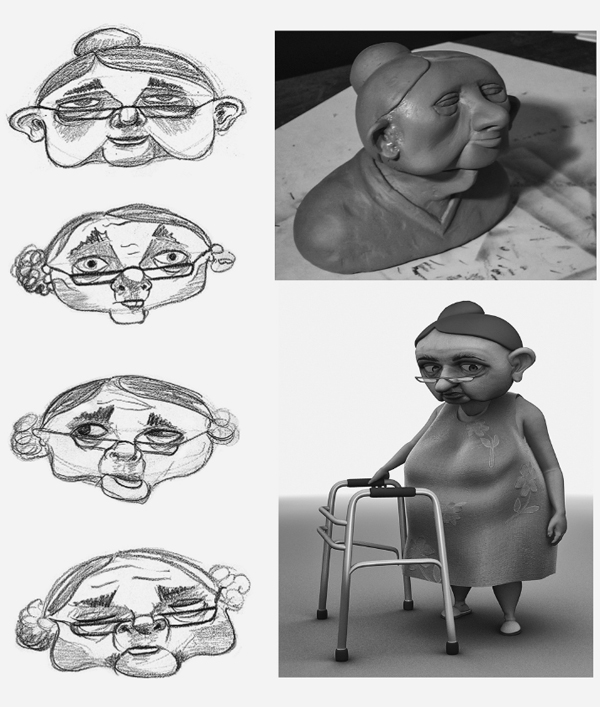

The polar pattern of a microphone is analogous to the type of lens used on a camera (Figure 3.6). However, unlike a camera lens, microphones pick up sound from all directions to some degree. The omni-directional pattern picks up sound uniformly from all directions. Consequently, this pattern produces the most natural sound when used in close proximity to the voice talent. Some microphones are designed with switchable patterns allowing for experimentation. Regardless of the pattern selected, it is wise to be consistent with that choice from session to session. Whether the dialogue is intended as scratch or if it will be used in the final soundtrack, avoid using microphones that are built in to a computer.

Figure 3.6 The Sound Characteristics Associated with Various Types of Polar Patterns

Recording Set-Up

Principal dialogue is recorded in mono with close microphone placement. The microphone is pointed at a downward angle with the diaphragm placed just above the nose. The recording script is placed on a well-lit music stand lined with sound absorption materials to prevent the unwanted reflections or rustling sounds. Avoid placing the microphone between the actor and other reflective surface such as computer screens, video monitors, or windows. Improper microphone placement can produce a hollow sounding distortion of the voice known as comb filtering. A pop-filter is often inserted between the talent and the microphone to reduce the plosives that occur with words starting with the letters P, B, or T. Headphones are usually required when shooting (recording) ADR with three preparatory beeps; many actors like to keep one ear free so they can hear their voice naturally. In some workflows, multiple characters are recorded simultaneously to capture timings of lines interacting and to allow the actors to react to other performers. With this approach, it is still advisable to mike up each character for greater separation and control in postproduction.

Cueing a Session

In pre-animation, scratch takes of principal dialogue are recorded wild (non-sync) and cued on a single track by character. Mixers have the option of recording individual takes on nested playlists or multiple audio tracks. With either approach, all takes can be displayed simultaneously. However, the playlist technique conserves track count, makes compositing easier, and provides a convenient track show/hide option. See Chapter 6 for a more detailed explanation on digital cueing and preparatory beeps.

Preparing Tracks for Lip Sync

Some directors prefer to keep individual takes intact rather than creating a composite performance. This approach preserves the natural rhythm of each line while also reducing editorial time. In the second approach, multiple takes are play-listed and portions of any given take are rated and promoted to a composite playlist. When compositing dialogue, the most transparent place to cut is during the spaces between words. With this type of edit, the main concerns are matching the level from take-to-take and developing a rhythm that feels natural. If an edit must be made within a word, cutting on the consonants is the most likely edit to preserve transparency. Consonants create short visible waveforms with little or no pitch variations and are easily edited. It is very difficult to match a cut occurring during a vowel sound due to the unpredictable pitch variations that occur from take-to-take. Regardless of the approach used, once the director settles on a take (circled take), it is delivered to the animator for track reading.

Lip Sync Animation

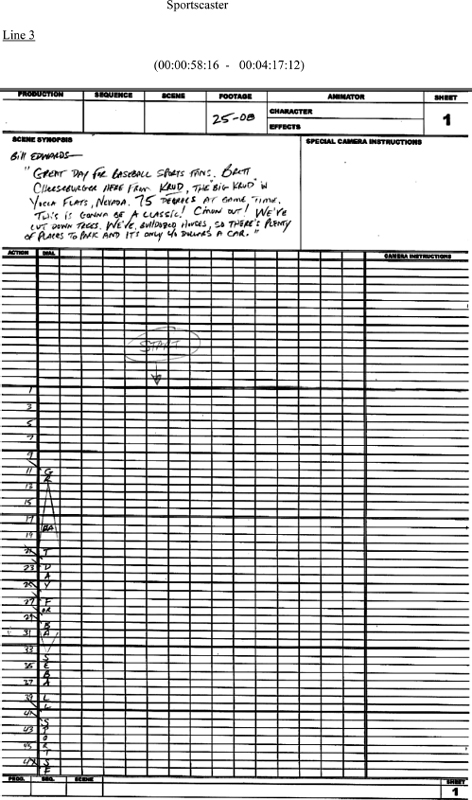

Track reading is an art unto itself. The waveforms displayed in a digital track-reading program represent more sonic events than need be represented visually. Phrases like “Olive Juice” and “I love you” produce similar waveforms unless one places the em fah sis on a different sill ah bull. Animators learn to identify the important stress points and determine what mouth positions are needed to convey the dialogue visually. Track readers map the dialogue on exposure sheets like the one shown in Figure 3.7. They scrub the audio files and listen for these stress points, marking specific frames where lip sync needs to hit. At the most basic level, consonants like M, P, and B are represented with a closed mouth position. Vowels are animated with an open mouth position. Traditional animators use exposure sheets or applications like Flipbook to mark specific frames for mouth positions.

Figure 3.7 Exposure Sheet for Pasttime (2004)

In 3D animation, the animator imports the dialogue audio files into the animation software, key framing the timeline at points where lip sync needs to hit. Many animators begin lip sync by animating body gestures and facial expressions that help the audience read the dialogue. They view these gestures and facial expressions as an integral part of the dialogue. When effectively executed, this approach leads the audience to perceive tight sync regardless of the literal placement.

You really can’t hone in on the character until you hear the actual voice you’re going to have.

(Horton Hears a Who!)

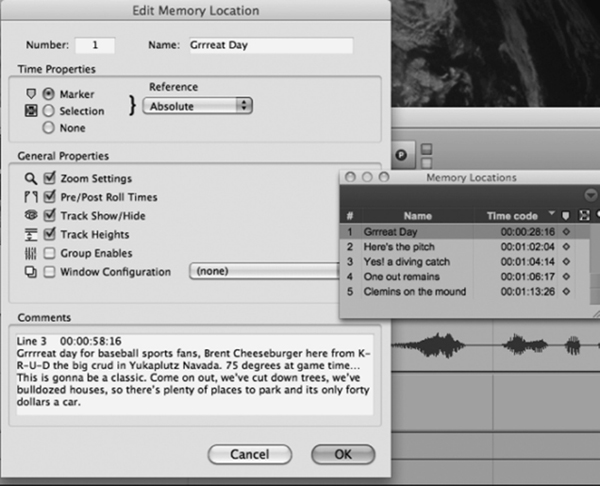

ADR

Once the lip sync animation is completed, any changes to the existing dialogue must be recorded in sync to picture in a process known as ADR or replacement dialogue. When recording replacement dialogue, the editor cues each line to a specific time code location within the character’s respective track. Three preparatory beeps are placed in front of the cue at one-second intervals to guide the voice actor’s entrance. Alternatively, streamers and punches are overlaid on the video to provide a visual preparation for an entrance. Some DAWs provide a memory location feature useful for cueing ADR digitally (Figure 3.8). With this feature, the location of individual cues can be stored in advance and quickly recalled at the session.

Figure 3.8 Memory Locations for Digital Cues

Whether recorded as scratch, final dialogue, or ADR, there are many objective criteria for evaluating recorded dialogue. It is the responsibility of the dialogue mixer to ensure that the dialogue is recorded at the highest possible standards. The following is a list of common issues associated with recorded dialogue.

![]() Sibilance — Words that begin with s, z, ch, ph, sh, and th all produce a hissing sound that, if emphasized, can detract from a reading. Experienced voice talents are quick to move off of these sounds to minimize sibilance. For example, instead of saying “sssssnake” they would say “snaaaake” maintaining the length while minimizing the offending sibilance. Moving the microphone slightly above or to the side of the talent’s mouth (off-axis) will also reduce sibilance. In rare cases, sibilance can be a useful tool for character development. Such was the case with Sterling Holloway’s hissing voice treatment of Kaa, the python in the Walt Disney feature The Jungle Book (1967).

Sibilance — Words that begin with s, z, ch, ph, sh, and th all produce a hissing sound that, if emphasized, can detract from a reading. Experienced voice talents are quick to move off of these sounds to minimize sibilance. For example, instead of saying “sssssnake” they would say “snaaaake” maintaining the length while minimizing the offending sibilance. Moving the microphone slightly above or to the side of the talent’s mouth (off-axis) will also reduce sibilance. In rare cases, sibilance can be a useful tool for character development. Such was the case with Sterling Holloway’s hissing voice treatment of Kaa, the python in the Walt Disney feature The Jungle Book (1967).

![]() Peak Distortion — A granular or pixilated sound caused by improper gain staging of the microphone pre-amp or from overloading the microphone with too much SPL (sound pressure level). Adjust the gain staging on the microphone pre-amps, place a pad on the microphone, move the source further from the microphone, if using a condenser microphone, consider a dynamic microphone instead.

Peak Distortion — A granular or pixilated sound caused by improper gain staging of the microphone pre-amp or from overloading the microphone with too much SPL (sound pressure level). Adjust the gain staging on the microphone pre-amps, place a pad on the microphone, move the source further from the microphone, if using a condenser microphone, consider a dynamic microphone instead.

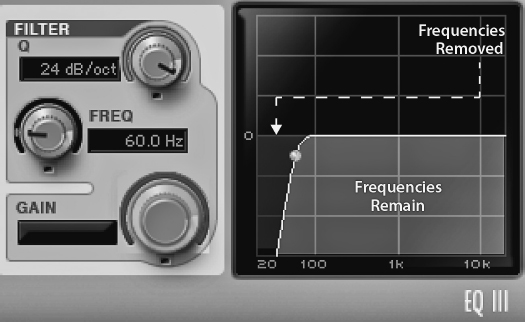

![]() Plosives (Wind Distortion) — Words that begin with the letters b, p, k, d, t, and g produce a rapid release of air pressure that can cause the diaphragm to pop or distort. Plosives can be reduced or prevented with off-axis microphone placement or through the use of a pop-filter. Some takes can be improved by applying a high-pass filter set below the fundamental frequency of the dialogue to reduce plosives.

Plosives (Wind Distortion) — Words that begin with the letters b, p, k, d, t, and g produce a rapid release of air pressure that can cause the diaphragm to pop or distort. Plosives can be reduced or prevented with off-axis microphone placement or through the use of a pop-filter. Some takes can be improved by applying a high-pass filter set below the fundamental frequency of the dialogue to reduce plosives.

![]() Proximity Effect — When voice talent is positioned in close proximity to a directional microphone, there is the potential for increased bass response, causing a boomy sound that lacks clarity. This proximity effect is sometimes used to advantage to create a fuller sound. To reduce this effect, re-position the talent further from the microphone or consider using an omni-directional pattern. A bass roll-off or high-pass filter (Figure 3.9) can also be used to effectively manage proximity effect.

Proximity Effect — When voice talent is positioned in close proximity to a directional microphone, there is the potential for increased bass response, causing a boomy sound that lacks clarity. This proximity effect is sometimes used to advantage to create a fuller sound. To reduce this effect, re-position the talent further from the microphone or consider using an omni-directional pattern. A bass roll-off or high-pass filter (Figure 3.9) can also be used to effectively manage proximity effect.

![]() Nerve-related Problems — Recording in a studio is intimidating for many actors. The sense of permanence and a desire for perfection often produce levels of anxiety that can impact performance. Signs of anxiety include exaggerated breathing, dry mouth, and hurried reading. It is often helpful to show the talent how editing can be used to composite a performance. Once they learn that the final performance can be derived from the best elements of individual takes, they typically relax and take the risks needed to deliver a compelling performance.

Nerve-related Problems — Recording in a studio is intimidating for many actors. The sense of permanence and a desire for perfection often produce levels of anxiety that can impact performance. Signs of anxiety include exaggerated breathing, dry mouth, and hurried reading. It is often helpful to show the talent how editing can be used to composite a performance. Once they learn that the final performance can be derived from the best elements of individual takes, they typically relax and take the risks needed to deliver a compelling performance.

![]() Lip and Tongue Clacks — Air conditioning and nerves can cause the actor’s mouth to dry out. This in turn causes the lip and tongue tissue to stick to the inside of the mouth, creating an audible sound when they separate. Always provide water for the talent throughout the session and encourage voice actors to refrain from drinking dairy products prior to the session.

Lip and Tongue Clacks — Air conditioning and nerves can cause the actor’s mouth to dry out. This in turn causes the lip and tongue tissue to stick to the inside of the mouth, creating an audible sound when they separate. Always provide water for the talent throughout the session and encourage voice actors to refrain from drinking dairy products prior to the session.

![]() Extraneous Sounds — Sounds from computer fans, florescent lights, HVAC, and home appliances can often bleed into the recordings and should be addressed prior to each session. In addition, audible cloth and jewelry sounds may be captured by the microphone due to close placement of the microphone to the talent. It is equally important to listen for unwanted sound when recording dialogue.

Extraneous Sounds — Sounds from computer fans, florescent lights, HVAC, and home appliances can often bleed into the recordings and should be addressed prior to each session. In addition, audible cloth and jewelry sounds may be captured by the microphone due to close placement of the microphone to the talent. It is equally important to listen for unwanted sound when recording dialogue.

![]() Phase Issues — Phase issues arise when the voice reflects off a surface such as a script, music stand, or window and is re-introduced into the microphone. The time difference (phase) of the two signals combine to produce a hollow or synthetic sound. Phase can be controlled by repositioning the microphone and placing sound absorbing material on the music stand.

Phase Issues — Phase issues arise when the voice reflects off a surface such as a script, music stand, or window and is re-introduced into the microphone. The time difference (phase) of the two signals combine to produce a hollow or synthetic sound. Phase can be controlled by repositioning the microphone and placing sound absorbing material on the music stand.

![]() Extreme Variations in Dynamic Range — Variations in volume within a vocal performance contribute greatly to the expressive quality and interpretation. Unfortunately, dialogue performed at lower levels often gets lost in the mix. Equally problematic is dialogue performed at such high levels as to distort the signal at the microphone or pre-amp. A compressor is used to correct issues involving dynamic range. Compressors will be covered at greater length in Chapter 7.

Extreme Variations in Dynamic Range — Variations in volume within a vocal performance contribute greatly to the expressive quality and interpretation. Unfortunately, dialogue performed at lower levels often gets lost in the mix. Equally problematic is dialogue performed at such high levels as to distort the signal at the microphone or pre-amp. A compressor is used to correct issues involving dynamic range. Compressors will be covered at greater length in Chapter 7.

![]() Handling Noise — Handling noise results when the talent is allowed to hold the microphone. Subtle finger movements against the microphone casing translate to thuddy percussive sounds. The actors should not handle microphones during a dialogue session. Instead, the microphone should be hung in a shock-mounted microphone cradle attached to a quality microphone stand.

Handling Noise — Handling noise results when the talent is allowed to hold the microphone. Subtle finger movements against the microphone casing translate to thuddy percussive sounds. The actors should not handle microphones during a dialogue session. Instead, the microphone should be hung in a shock-mounted microphone cradle attached to a quality microphone stand.

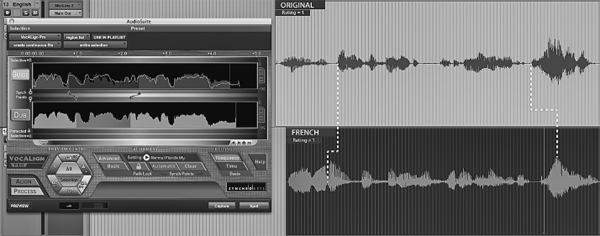

Dialogue Editing

The dialogue editor is responsible for cleaning tracks, compositing takes, tightening sync, and preparing tracks for delivery to the mix stage. Even when recorded in studio conditions, dialogue tracks often contain environmental noise, rustling of paper, cloth sounds, headphone bleed, and extraneous comments from the voice actor. The dialogue editor removes these unwanted sounds using a variety of editing and signal processing techniques. Dialogue editors are also responsible for tightening the sync for ADR and foreign dubs. Even the most experienced voice actors have difficulty matching the exact rhythm of the original dialogue. Dialogue editors resolve sync issues using editing techniques and time compression/expansion (TC/E) software. Most DAWs come with TC/E plug-ins to facilitate manual sync adjustments. However, specialized plug-ins such as Vocalign were developed specifically for tightening lip sync. Vocalign maps the transients of the original dialogue and applies discrete time compression/expansion to the replacement dialogue. For foreign dubs, Vocalign has a sync point feature that allows the user to align specific words from both takes (Figure 3.10). Once the editing and signal processing is completed, the dialogue editor consolidates and organizes the tracks in a manner that is most facilitative for the mixing process.

You want to create the illusion of tight sync without losing the feel.

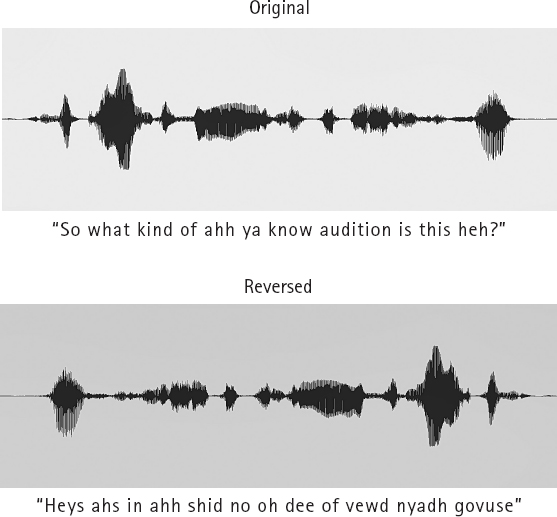

Designed Languages

Some animations call for a designed or simulated language, such as the alien language of the Drej in Titan A.E. (2000). Simulated dialogue establishes plausible communication in the context of a fantasy. One common approach is to reverse an existing line of dialogue (Figure 3.11). The resultant line contains a logical structure but lacks intelligibility.

Since the resultant dialogue is unintelligible, subtitles are often added to provide a translation. Signal processing is yet another design tool used to transform dialogue for effect. The familiar robotic sounds heard in films like Wall-E (2008) are achieved by processing ordinary dialogue with Vocorders, harmonizers, and other morphing plug-ins.

Some approaches, though less technical in execution, are equally effective. For example, the adult voices in Charlie Brown’s world are mimicked with brass instruments performed with plungers. With this approach, communication is implied while minimizing the presence of adults. The humorous Flatulla dialect heard in Treasure Planet (2002) was achieved by combining armpit farts with a variety of vocal effects. In the 1935 Silly Symphony Music Land, lifelike musical instruments inhabit the Land of Symphony and the Isle of Jazz. Rather than mime the narrative, director Wilfred Jackson chose to represent dialogue with musical phrases performed in a speech-like manner. Music Land is an entertaining attempt at making us believe that music is truly a universal language, capable of bridging any Sea of Discord.