Sound Effects (SFX)

Overview

Animation provides the sound editorial department with a silent backdrop from which to create a sonic world. Whether cutting hard effects, developing backgrounds, creating design elements, or recording Foley effects, the absence of production audio associated with live action film is often liberating. As with score, readily identifiable styles of FX and Foley have emerged that are associated with innovated sound designers, production companies, and animation genres. The use of sound effects for dramatic purposes can be traced back to ancient Greek theater. In the beginning of the twentieth century, Radio Theater became the primary outlet for storytelling. The techniques developed for Radio Theater would become the foundation for sound in cinema. Treg Brown and Jimmy MacDonald are two of the earliest known sound designers. Brown is known for his creative blending of subjective and realistic sounds to create the unique SFX style associated with the early Warner Brothers animation. Jimmy MacDonald is remembered for developing many of the innovated sound making devices that can be heard in decades of Disney classics. In the 1950s, Wes Harrison “Mr. Sound Effects” demonstrated the power of vocalizations that can be heard in many of the Disney and MGM productions of that decade. Wes proved that many of the best SFX are found right under our noses. When Hanna and Barbera left MGM, they brought a large portion of the SFX library used for Tom and Jerry with them. With the help of Pat Foley and Greg Watson, Hanna and Barbera developed one of the most iconic SFX libraries in the history of animation. Contemporary sound designers such as Gary Rydstrom, Randy Thom, Ben Burtt, and Dane Davis continue the strong tradition established by these innovators.

Thanks to the movies, gunfire has always sounded unreal to me, even when being fired at.

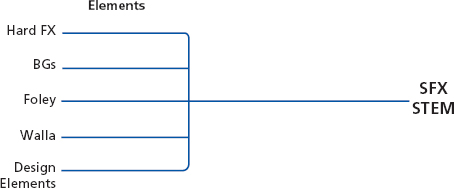

Figure 5.1 Elements Contributing to the SFX Stem

The SFX Stem

The SFX stem is divided into several layers including hard effects, Foley, backgrounds (BGs), Walla, and Design Elements. Together, these layers are responsible for the majority of the tracks comprising a soundtrack. Hard effects and Foley cover much of the basic sounds and movements in the soundtrack. Hard effects differ from Foley in that they are cut or edited rather than performed. Foley is such an important element in animation that it will be discussed in a separate chapter. Until recently, backgrounds (BGs) were rarely used in animation and underscore often provided the environmental background. Today, BGs are a common element in the soundtrack, providing the sonic backdrop for the animated world. In the opening sequence of Disney’s Dinosaur (2000), notice the many different BGs represented as the Iguanodon egg travels through the multitude of environments. In Pixar’s Toy Story, the backgrounds heard outside Andy’s window support his warm and playful nature. In contrast, the backgrounds accompanying Sid accentuate his sadistic and edgy qualities. Walla, though built on non-descript dialogue, functions in a similar fashion to backgrounds and is included in the SFX stem. As the name implies, design elements are created by layering sounds to cover sonically complex objects critical to the narrative.

The challenging thing about the animated film is that you have to entirely invent the world.

Temp Tracks and Spotting Sessions

Animation differs from live action in that sound editorial need not wait for picture lock to begin soundtrack development. Temp FX, scratch dialogue, and temp music are useful when developing shots and scenes with an animatic. They help establish timings, mood, and environments, while providing important story points that may not be visually represented. Temp effects provide additional feedback for motion tests such as walk cycles and accelerating objects. As the animation process nears completion, the film is screened (spotting session) with the director, the supervising sound editor, and lead sound editors to finalize SFX and dialogue for the film. Since the soundtrack for an animation is entirely constructed, every sound is deliberate. Important considerations for the inclusion of sound are:

![]() Is the sound object important to the narrative or is it ambient?

Is the sound object important to the narrative or is it ambient?

![]() Is the sound object intended to support realism or fantasy?

Is the sound object intended to support realism or fantasy?

![]() What are the physical characteristics of the sound object?

What are the physical characteristics of the sound object?

![]() How does the sound object move or interact in the environment?

How does the sound object move or interact in the environment?

![]() Are there any existing models to base the design on?

Are there any existing models to base the design on?

The Sound Department

The sound department is responsible for the development of SFX and Dialogue Stems. The head of the sound editorial department is the supervising sound editor. The Sups (“soups”) are responsible for assembling a crew, developing and managing the audio budget, developing a post-production schedule, developing a workflow, making creative decisions, and insuring that the delivery requirements are properly met. Additional FX, Dialogue, and Foley editors are brought in based on post-production demands, schedules, and available budget. For larger projects, the supervising sound editor may appoint individual editors to take a lead or supervising role in each area. Sound designers are enlisted to create the creative design elements. Foley and dialogue mixers are enlisted to record Foley walkers and voice actors.

You learn that the most important thing that you can do as a sound designer is to make the right choice for the right sound at the right moment in a film.

Sound Editors

Sound editors cut or edit elements (SFX) and dialogue to picture. They are responsible for insuring that audio properly syncs to image and conforms in length. Sound editors are also responsible for cleaning up the tracks and re-conforming the soundtrack when additional picture edits are made. There are two basic workflows for sound editing. The first involves assigning individual reels to editors who are responsible for all of the elements within that reel. In the second workflow, editors are given responsibility for specific elements across multiple reels. The first approach is useful when schedules are compressed; the second approach facilitates continuity from reel-to-reel. The lead or Supervising SFX, Dialog, and Foley editors are also asked to cue sessions for ADR and Foley as well as preparing the tracks for the mix stage.

If I find a sound isn’t working within a scene, I’ll abandon the science and go with what works emotionally.

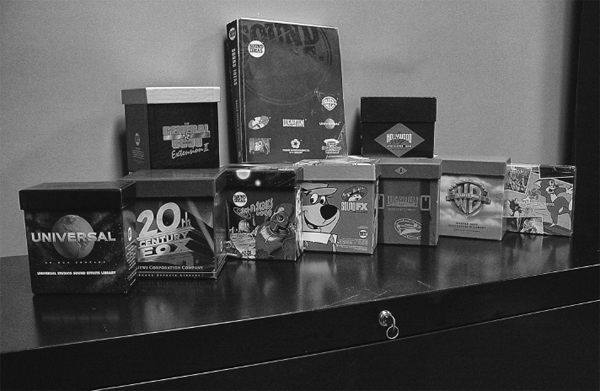

Many of the sounds that editors cut to picture are pulled from commercial SFX libraries (Figure 5.2). These libraries are expedient and cost effective, containing hard-to-obtain sounds such as military equipment, dangerous animals, and historical props. As such, they are a practical reality in modern media production. Database software has been developed for the specific purpose of managing these extensive libraries. They contain search engines that recognize the unique metadata associated with sound effects. In addition, they allow the sound editor to preview individual sounds and transfer them to media editing software. Numerous delivery formats are in use for commercial sound effects, including CDs, preloaded hard drives, and on-line delivery. Hollywood Edge, Sound Ideas, and SoundStorm are three popular SFX libraries that deliver in CD and hard drive formats. Individual SFX can also be purchased online at www.sounddogs.com and www.audiolicense.net. All of the major commercial libraries are licensed as buyouts, meaning the SFX can be used on any media project at no additional cost. There are many sites on the Internet offering free SFX downloads: many of these sites contain highly compressed files taken from copy-protected libraries. Therefore to get the best quality and to protect the project from infringement, additional care should be taken when using files obtained in this manner.

Figure 5.2 Commercial SFX Libraries Are a Practical Reality in Media Production

Searching SFX Libraries

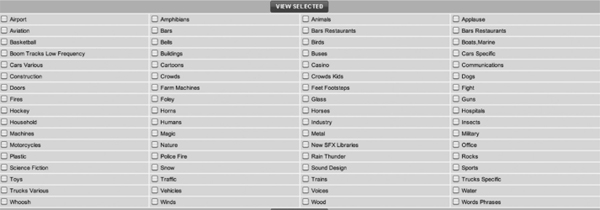

In the early years, individual sound effects were stored on film and cataloged using note cards. Today, we can store thousands of hours of SFX on a single drive and access them using customized database software. To effectively search a SFX library, the sound editor must acquire a very specialized vocabulary and some basic search techniques (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.3 Categories in the SoundDogs Online Library

Figure 5.4 The Search Engine for Soundminer

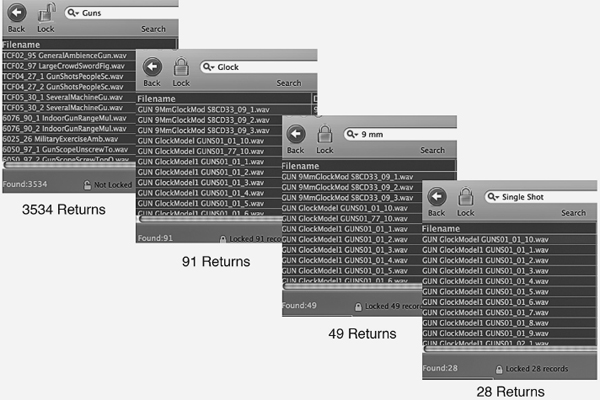

Most search engines use Boolean logic which utilizes three basic qualifiers to narrow a search; and, or, and not. To narrow a search and to make the search results dependent on the presence of multiple keywords, use AND in conjunction with keywords (e.g., gLASS AND BREAKING). To expand a search utilizing independent keywords, use OR in conjunction with keywords (e.g., GLASS OR BREAKING). To narrow a search and exclude specific keywords, use NOT in conjunction with keywords (e.g., NOT BREAKING). Parentheses allow users to combine AND, OR, and NOT in the search; for example, GLASS AND (PLATE NOT EYE) will produce a more refined result. Placing quotations on a group of terms focuses the search to specific phrases that contain all keywords in sequence; for example, GLASS AND BREAKING can yield a multitude of off-target results, but “GLASS BREAKING” greatly limits the search. You can combine keyword searching with phrase searching as well (e.g., LAUGHTER AND “LARGE AUDIENCE”). The Soundminer application has a unique feature called lock search that allows the user to refine the search with subsequent keywords (Figure 5.5). For example when searching guns in the database shown in Figure 5.5, we get 3,534 search results. By locking down the search and typing the Glock modifier, we refine the search to 91 results. The modifiers 9 mm and Single Shot refine the search to 49 and 28 returns, respectively.

Figure 5.5 Narrowing Results using a Locked Search

Developing an Original SFX Library

Creating an Original Library

Commercial libraries are cost effective and convenient, but they also have their limitations. Many effects are derived from low-resolution audio sources such as archival film stock and aged magnetic tape. As commercial libraries, they are non-exclusive and can be heard on a multitude of projects. In addition, some library effects (such as those of Hanna-Barbera) are icons for well-known projects, therefore users run the risk of attaching unwanted associations to new projects. For these reasons, many SFX editors prefer to record original sound effects uniquely suited to a specific project. Sound effects can be recorded in a studio under controlled conditions or in the field. A sound editor armed with a digital recorder, microphones, and headphones can capture a limitless number of recordings. Many great sound effects are obtained by accident, but not without effort.

Field Recorders

Hard disc recorders provide a practical solution to a variety of recording needs including field acquisition of SFX (Figure 5.6). These recorders can capture audio at high bit-depths and sampling rates in file formats supported by most audio editing software applications. The field recorders shown in Figure 5.6 are battery operated for increased mobility. They utilize a file based storage system which facilitates immediate transfer using the drag and drop method. The Zoom features built-in microphones, alleviating the need for additional microphone cables.

Figure 5.6 The H4n Zoom and Sound Device Hard Disc Recorders Used in Field SFX Acquisition

Microphone selection and placement represent the first of many creative decisions required to effectively capture SFX. The choice between a dynamic and condenser microphone comes down to transient response, frequency response, sensitivity, and dynamic range. The dynamic microphone is most effective for close positioning of a microphone on a loud signal. Condenser microphones are most effective at capturing sounds containing wide frequency and dynamic ranges and are particularly useful in capturing sources from greater distances. The polar pattern on a microphone is analogous to the lens type on a camera. Cardioid patterns are more directional and reject sounds from the side and the back, and are therefore useful when sound isolation is needed. Omni-directional microphones pick up sound evenly at 360 degrees, capturing a more natural sound but with additional environmental noise. Some microphones have built-in high-pass filters to minimize wind noise, low-frequency rumble, and proximity effect. Many sounds can only be obtained from a distance, requiring highly directional microphones like the shotgun and parabolic microphones.

Field Accessories

When field recording, it is wise to remember that you only have what you bring with you in your kit, so plan carefully. The following is a list of accessories that are useful for the many situations that can arise in the field.

- Microphone cables come in a variety of lengths. It is a good practice to include cables of varied lengths in your field kit. A three-foot cable is useful for hand-held microphones, while longer cables are needed for boom pole work and multiple microphone placements from varied distances.

- Field recording without headphones is like taking a photograph with your eyes closed. Headphones reveal sound issues such as handling noise, wind noise, and microphone overloading that are not indicated on the input meters. Headphones also bring to the foreground sounds to which our ears have become desensitized, such as breathing, cloth movements, and footsteps. Headphones should sufficiently cover the ears and have a good frequency response. The earbuds used for portable music devices are not sufficient for this purpose. The windscreens that come with most microphones provide limited protection from the low frequency noise caused by wind.

- The wind sock is effective at reducing wind distortion with minimum impact on frequency response (Figure 5.7). Wind socks are essential for outdoor recording, even when conditions are relatively calm.

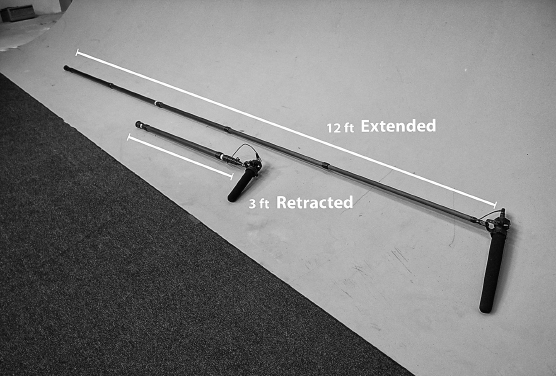

- There are many uses for a boom pole outside of its traditional role in live-action production audio (Figure 5.8). Boom poles are thin and lightweight and can be varied in length to overcome physical barriers that effect microphone placement. They can also be used to sweep a sound object, effectively recording movements without changing perspective.

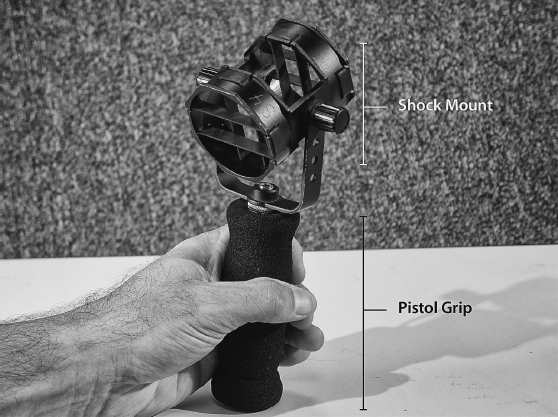

- Shock mounts and padded pistol grips are used to isolate the microphone handling noise (Figure 5.9). Shock mounts can be attached to pistol grips or boom poles.

- Moisture has an adverse effect on the performance and life of microphones and recording equipment. Humidity and condensation can be a particular problem, causing static pops in the signal. Zip Lock Bags, sealable plastic containers, and Silicone Gel Packs take up very little space, help organize equipment, and provide protection against moisture related issues. Often when you are recording in natural environments, biting insects can become a distraction. If you use bug spray, avoid brands that use DEET as this chemical is very corrosive when it comes in contact with electronic equipment. Always bring an extra supply of batteries.

Suggestions for Field Recording

Record Like an Editor

The purpose of field recording is to create a library that is useful for sound editing. Record with that in mind, leaving sufficient handles after each take, recording with multiple perspectives, and varied performances.

Objectivity

Often when we go into the field to record, we listen so intently for the sound that we are trying to capture that we fail to notice other sounds that if recorded, may render the take unusable. Our ability to filter out certain sounds while focusing on others is known as the cocktail effect. It is important for the field recordists to remain objective at all times and to record additional safety takes to guard against this perceptual phenomenon.

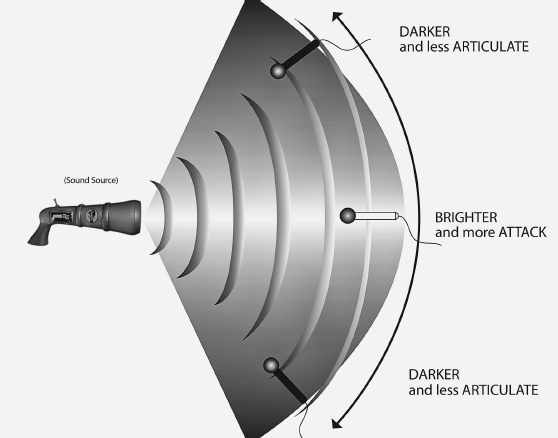

Area-Specific Frequency Response

The placement of the microphone too close to an object produces an area-specific frequency response that makes the resulting sound hard to identify. Consider the context and proximity by which most audiences experience a specific object and use that information to base your initial microphone placement. Most sound objects are bright and articulate on-axis and progressively darker and rounder as you move off-axis (Figure 5.10).

Figure 5.10 Sound Radiation Pattern

Signal-To-Noise Ratio

The world is filled with extraneous sounds that make it increasingly challenging to capture clean recordings. The balance between the wanted sound (signal) and the unwanted sound (noise) is referred to as signal-to-noise ratio (S/N ratio). Selecting remote locations or recording during quiet hours can minimize these issues.

Dynamic Range

Field effects recordists should be familiar with the dynamic range (volume limitations) of their equipment and the volume potential of the signals being recorded. Distortion results when the presenting signal overloads the capacity of either the microphone or recorder. In digital audio, distortion is not a gradual process; therefore, when setting microphone levels, it is important to create additional headroom in anticipation for the occasional jumps in volume that often occur. A good starting point is -12 dBfs. For sounds that are not easily repeated, consider using a multiple-microphone approach that takes advantage of varied microphone types, polar patterns, placements, and trim levels.

File Management

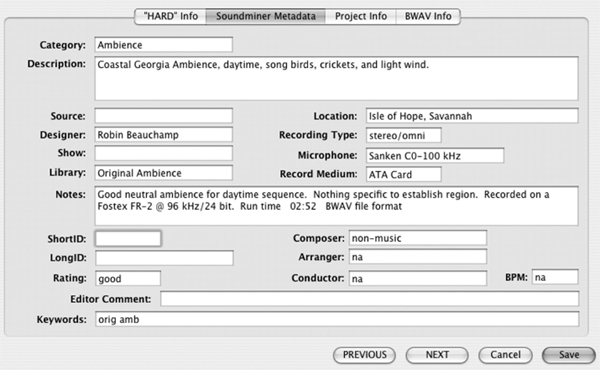

Field recording is time intensive, often yielding only a relatively small percentage of the usable material. As sound transfers and cataloging do not always occur immediately after a shoot, it can sometimes be difficult to recall the specifics of individual takes. For this reason, many field recordists place a vocal slate at the beginning or end (tail slate) of each take. A vocal slate can include any information (metadata) that will become affixed to the file in a database. Figure 5.11 shows many of the metadata fields associated with SFX management software.

Figure 5.11 Soundminer Metadata

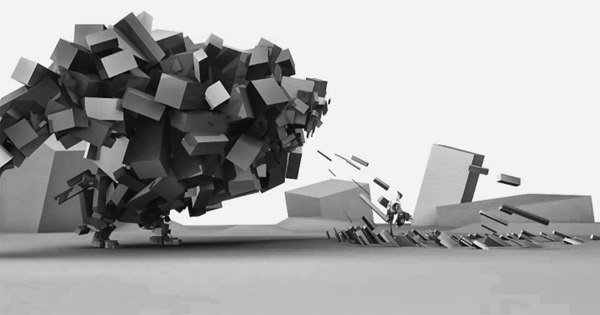

Sound objects that are complex or subjective in nature often require more creative approaches to their design. The job of creating design elements is assigned to highly experienced sound editors, known as sound designers. Sound designers use techniques that transcend editing and include sampling, MIDI, synthesis, and signal processing. Examples of design elements include fictitious weaponry, futuristic vehicles, or characters that are either imagined or have ceased to exist. Design elements are typically built-up or layered from a variety of individual elements. It is important to develop an understanding of how characters or objects interact in the environment, what they are made of, and their role in the narrative. When creating a design element, it is also important to deconstruct the sound object to identify all related sounds associated with the object or event; for example, a customized gun sound might be derived from any or all of the key elements shown in Table 5.1

Table 5.1 Individual Elements of a Cinematic Gun

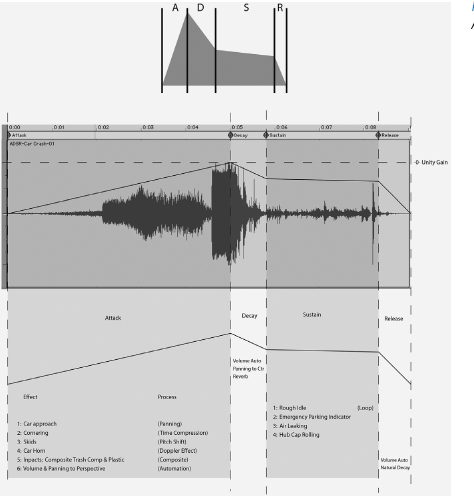

The sound envelope (ADSR) can be a useful tool for organizing the individual layers that comprise a design element (Figure 5.12). Once each element is identified, sounds can be pulled from a library and combined through editing.

The trick is to make the sounds useful to the scene, but not make them so attention getting that they snap you out of the movie.

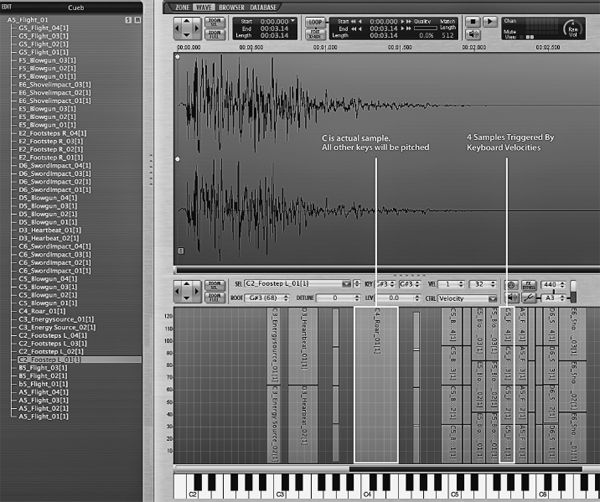

Performing Design Elements

Since the 1980s, sound designers have been using sampling technology such as the Synclavier to create and perform complex design elements. This approach can be emulated today using software (virtual) samplers and a MIDI keyboard (Figure 5.14). Once the individual elements for the object are identified and pulled from a library, they are assigned to specific keys on a MIDI controller. Multiple samples can be assigned to a single key and triggered discretely based with varied key velocities. Sounds mapped to a specific key will play back at the original pitch and speed. However, they can also be assigned to multiple keys to facilitate pitch and speed variations. Various components of the design element can be strategically grouped on the keyboard, allowing the sound designer to layer a variety of sounds simultaneously. For this approach, systematic file labeling is required to insure the proper key and velocity mapping. For example C#3_Glassshards_03 indicates that the glass shard will be assigned to C#3 on the keyboard and be triggered at the 3rd highest velocity setting. Once a patch is created, individual elements can be performed to image, creating with a multitude of variations in an efficient and organic manner.

I’m often creating “chords” of sounds.

(Shark Tale)