Music

Overview

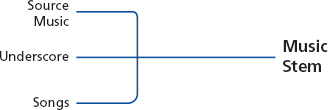

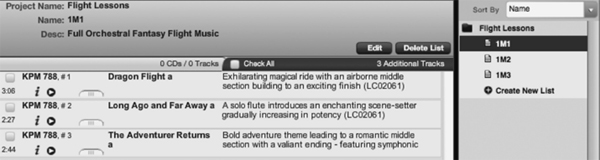

The music stem or score is perhaps the most difficult component of the soundtrack to describe in words. Ironically, score rather than SFX often drive films that lack dialogue. Each musical entrance in a soundtrack is called a cue. A cue can underscore a scene or represent a source such as a radio or phonograph. In addition to source and underscore, many films use music for title, montage, and end credit sequences. The labeling convention for a cue is 1M1, the first number representing the reel and the last number representing the order in which it occurs. Cues are often given titles representative of the scenes they accompany. The blueprint for the score is created at the spotting session that occurs immediately after picture lock (no further picture editing). Film composers begin scoring immediately after the spotting session and are expected to compose two to five minutes of music each day. If copy-protected music is being considered, a music supervisor is brought in at the earliest stage to pursue legal clearance. The music editor has responsibilities for developing cue sheets, creating temp tracks, editing, synchronization, and preparing the score for the re-recording mixer. There are many additional roles related to the development of the score such as orchestrators, musicians, music contractors, and recording engineers.

Figure 4.1 Elements in the Music Stem

People sing when they are too emotional to talk anymore.

Underscore

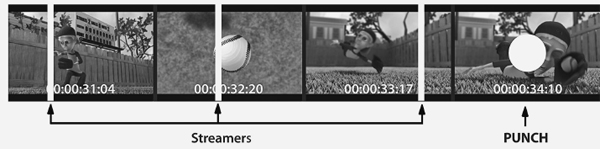

During the golden age of animation, underscore was anything but subtle. Most of the action on and off-screen was covered by musical cues that were often indistinguishable from the SFX stem. Composers of this era pioneered the integration of twentieth-century musical styles and performance techniques. Even though they pushed the musical boundaries, their scores remained both playful and accessible. In contemporary animation, the style and approach of underscore is oftentimes indistinguishable from live action cues. Underscore can play through a scene or hit with specific action. Cues that play through a scene provide a linear element in the soundtrack, smoothing edits and creating emotional continuity within a scene. The practice of hitting the action with musical accents is a long established convention. In addition to hitting the action, musical cues occasionally hit with dialogue as well. For example, in the film Anastasia (1997), Comrade Phlegmenkoff’s line “And be grateful, too” is punctuated with orchestral chords to add emotional weight to the delivery.

I’m a storyteller . . . and more or less in the food chain of the filmmaking process, I’m the last guy that gets a crack at helping the story.

Source Music

Source music is the diegetic use of songs to contribute to the implied reality of the scene. To maintain this realistic feel, source music is often introduced “in progress,” as if the audience were randomly tuning in. Songs are commonly used as source material, effectively establishing time period, developing characters, or acting as a cultural signifier. Source music also supports time-lapse sequences by changing literally with each shot. Source music can be either on-screen (emitting from a radio or phonograph) or off-screen (such as elevator music or a public address system). The songs used in source music are almost always selected for their lyric connection to the narrative. Source music is processed or futzed to match the sonic characteristics of implied sound source. Like hard effects, source music is treated like a SFX and panned literally to the on-screen position. Cues often morph or transition from source to underscore to reflect the narrative shift in reality typified by montage sequences and other subjective moments.

Songs

During the golden age of animation, familiar songs were routinely quoted instrumentally, and the implied lyrics were integral to the sight gags. Original songs such as “Some Day My Prince Will Come” from Snow White (1934) blended narrative lyrics with score to create a musical monologue. Walt Disney Studios was largely responsible for the animated musical, developing fairy tale stories around a series of songs performed by the characters. These songs are pre-scored, providing essential timings for character movements and lip sync. In animated musicals, it is not uncommon for a character’s speaking voice to be covered by a voice actor while the singing voice is performed by a trained vocalist. Great care is taken to match the speaking voice with the singing voice. An effective example of this casting approach can be heard in Anastasia, where Meg Ryan’s speaking voice flawlessly transitions to Liz Callaway’s vocals. A more recent trend in animation is the use of pre-existing songs as the basis for the score. This is known as a song score; examples of this approach include Shrek (2001), Lilo and Stitch (2002), and Chicken Little (2005). It is sometimes desirable to create a new arrangement of an existing tune as a means of updating the style or customizing the lyrics. An example of this occurs in Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius (2001) in a montage sequence where Thomas Dolby’s “She Blinded Me with Science” is covered by Melissa Lefton singing “He Blinded Me with Science” to reflect the POV of Cindy Vortex (Jimmy’s female adversary/love interest). Songs continue to play an important roll in short form independent animation, especially if the film does not incorporate dialogue. However, there are potential risks associated with the use of songs in animation. Songs can give a film a dated feel over time, which is why the accompaniments of songs in animated musicals are primarily orchestral. They also introduce the potential for copyright infringement, an issue that will be addressed later in this chapter.

Story is the most important thing . . . not the song as a song, but the song as development.

Title, Montage, and End Credit Sequences

Title, montage, and end credit sequences have a unique function in film and present unique scoring opportunities. Title sequence music can effectively establish the scale, genre, and emotional tone of the film. Composers can write in a more thematic style, as there is little or no dialogue to work around. A good example of title sequence music can be heard in 101 Dalmatians (1961). Here the music moves isomorphically and frequently hits in a manner that foreshadows the playful chaos that will soon follow. Montage sequences are almost always scored with songs containing narrative lyrics. The linear nature of songs and their narrative lyric help promote continuity across the numerous visual edits comprising a montage sequence. End credit music should maintain the tone and style established in earlier cues while also promoting closure. The end-credit score for animated musicals often consists of musical reprises re-arranged in modern pop styles suitable for radio play.

Workflow for Original Score

Rationale for Original Score

Directors often seek an original score that is exclusive, tailored, and free from preexisting associations. Original music can be an important tool for branding a film. The iconic themes and underscore heard in the Hanna-Barbera animations cannot be emulated without the drawing comparison. Original cues are tailored with hits and emotional shifts that are conceived directly for the picture. In concert music, there are many standard forms that composers use to organize their compositions. If these conventions were used as the basis for film scoring, form and tempo would be imposed on the film rather than evolving in response to the images. Music is known to encapsulate our thoughts and feelings associated with previous experiences. Filmmakers seek to avoid these associations and create unique experiences for their audience. With original score, cues can be written in a similar style without evoking past associations. Even when the music is of a specific style or period, it can be scored to create a timeless feel.

I aim in each score to write a score that has its own personality.

Temp Music

Temp music is perhaps the most effective vehicle for communicating the type of score required for a specific film. As the name implies, a temp (temporary) track is not intended for inclusion in the final soundtrack. Temp tracks are edited from pre-existing music to guide the picture editing process, facilitate test screenings, and provide a musical reference for the composer. The responsibility of creating a temp track often falls on a picture or sound editor. Editors select music that matches the style and dramatic needs as represented in the storyboards or animatic. The music is then edited and synced to create a customized feel for the score. Because the temp track is for internal use, copy-protected material is often utilized. Temp tracks can prove problematic if the director becomes overly attached and has difficulty accepting the original score.

The Spotting Session

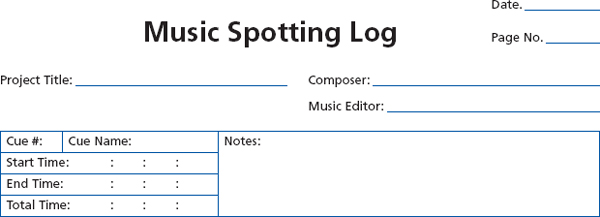

In animation, cues can be source, pre-score, or non-sync underscore. Pre-scored cues must be developed before the animation process begins as the characters are moving in sync to the musical beats. Some composers prefer to begin writing thematic material and underscore for the film as early as the storyboarding stage. However, most underscore cues are decided once the picture is locked. Here, the director meets with the composer and music editor to screen the film and discuss where music can best be contributing. The spotting session is an important opportunity for the director to clarify their vision for their film on a shot-by-shot basis. If a temp score exists, these cues are played for the composer to help clarify the style and intent. During the spotting session, the music editor takes detailed notes related to specific cues (Figure 4.3). From these notes, the music editor generates cue sheets outlining the parameters of each cue.

Figure 4.3 Spotting Log Template

Suggestions for identifying cues in a spotting session:

![]() Determine the importance of music for the scene.

Determine the importance of music for the scene.

![]() Look for opportunities in the scene where music can be brought in without drawing attention to itself.

Look for opportunities in the scene where music can be brought in without drawing attention to itself.

![]() Decide when the music should hit, comment, or play through the action.

Decide when the music should hit, comment, or play through the action.

![]() Be selective; wall-to-wall music tends to lose its effectiveness.

Be selective; wall-to-wall music tends to lose its effectiveness.

![]() Be open to all musical styles; allow the image, rather than personal taste, to influence decisions.

Be open to all musical styles; allow the image, rather than personal taste, to influence decisions.

Before you can set out and start scoring . . . one’s gotta be on the same page with the filmmakers.

Writing Original Cues

Film composers must be able to write in all styles and for a wide range of instruments. Chord progressions, rhythmic patterns, and instrumentation are elements that can be emulated to capture the essence of the temp track. They are often used to provide the foundation for an original theme resulting in a similar, yet legal cue. Today, most films are scored to digital video using extensive sample libraries that emulate a wide range of instrumentation. Much of the writing occurs in a project studio utilizing MIDI technologies, recording, and editing capabilities to fully produce each cue. The composer does not work directly with the animator when writing individual cues. Instead, they meet periodically to audition and approve individual cues. Composers use the feedback gained from these sessions to hone in on the musical direction for individual cues. It is important to note that additional picture edits occurring after this point can result in significant qualitative, budget, and scheduling implications. Most scores are created as works for hire, requiring the composer to surrender publishing rights to the production company. Creative fees are negotiated based on experience and the amount of music required. Smaller budget projects often require the composer to handle all tasks associated with producing the score. This type of contract is referred to as a package deal, and includes: orchestration, part writing, contracting musicians, recording, conducting, and music editing.

My job is to make every moment of the film and every frame of the film come to life.

The Scoring Session

Sample libraries have steadily improved, providing composers with access to a comprehensive set of orchestral, rock, and ethnic samples from which to orchestrate their cues. However, sample-based scoring can be time consuming and lack the expression and feel created with live musicians. Consequently, many larger projects use the traditional approach using live musicians at a scoring session. The space where the cues are recorded is called a scoring stage. Scoring sessions involve many people and resources, so planning is an important means of optimizing resources. The music editor attends the scoring session(s) to run the clock (synchronization) and to help evaluate individual takes. Due to budget realities and the limited access to qualified musicians, the blending of sequenced music with live musicians is becoming a common practice for a wide range of projects. Once the cues are completed, they are delivered to the music editor for additional editing and sync adjustments. From there, the tracks are delivered to the re-recording mixer in preparation for the final mix

Workflow for Production Libraries

Production Libraries

Hoyt Curtain (composer for Hanna-Barbera) developed a distinctive in-house music library for shows such as The Flintstones and The Jetsons. The cues contained in this library were re-used in subsequent seasons as well as other series. This provided Hanna-Barbera with a low cost music approach to scoring that also contributed to the continuity while promoting their brand. Commercially available production libraries have been developed for similar purpose. The days of “canned music” have long since passed and modern production libraries are providing a high quality, low cost, and expedient means of developing specialized cues or an entire score. The music tracks contained in commercial libraries are pre-cleared for use on audio/visual productions. Low-resolution audio files can be downloaded and cut into the temp, allowing the client to approve the cues in context. There are some disadvantages to production music including non-exclusivity, the need for costly editing, and the lack of variation for specific cues. The three types of production libraries are classified by their licensing specifications. Buy-out libraries are purchased for a one-time fee and grant the owner unrestricted use. Blanket licensing covers a specified use of a library for an entire project. Needle drops are the third and most expensive type of library. Needle drop fees are assigned per cue based on variables such as length, territory, distribution, and nature of the use. Most blanket and needle drop libraries provide online search, preview, delivery, and payment options.

Figure 4.4 Production Music Library from DeWolfe, available on disks or hard drive.

Searching a Library

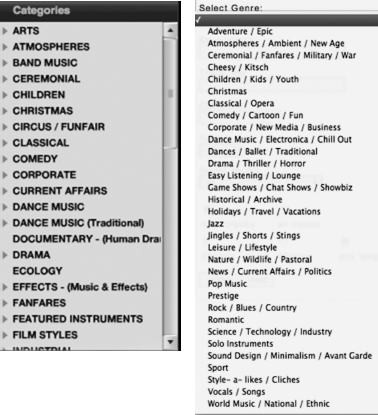

As with all scores, the process begins with a spotting session to determine where cues are needed and the nature of individual cues. This information guides the music editor in searching production libraries for musical selections that might potentially become music cues. Commercial production libraries can be rather expansive, containing thousands of hours of music. Most production companies have online search engines to assist the music editor in a search. Categories, keywords, and musical styles are the most common type of search modes (Figure 4.5). Categories are broad and include headings such as Instrumentation, Film Styles, National/Ethnic, and Sports. Keyword searches match words found in titles and individual cue descriptions. Emotional terms prove to be most effective when searching with keywords. Musical styles are also common to production library search engines. Many musical styles are straightforward but others are more difficult to distinguish. This is particularly true of contemporary styles such as rock, pop, and hip-hop. If you are unfamiliar with a particular style, find someone who is and get them to validate the style.

Figure 4.5 APM and DeWolfe Search Categories

Many online libraries contain a project management component in their browsers (Figure 4.6). This feature allows the music editor to pull individual cuts from the library and organize them by specific projects and cues. As with original score, there comes a point in the project where the director is brought in to approve the cues. The music editor can open a specific project and play potential cuts directly from the browser. Alternatively, they can download tracks and cut them to picture, allowing the director to audition and approve each cue in context (Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.6 Three Potential Cuts Saved in APM’s Project Manager

A skilled music editor can edit cues to create the illusion that the music was scored for a particular scene. They do this by matching the emotional quality of a scene, conforming cues to picture, and developing sync points. Oftentimes, it is the editing that “sells” a particular music selection. Once the cues are developed, the director is brought in to audition and approve the cue. Many of the techniques used by the music editors are also used by dialogue and SFX editors and will be discussed in greater length in Chapter 8.

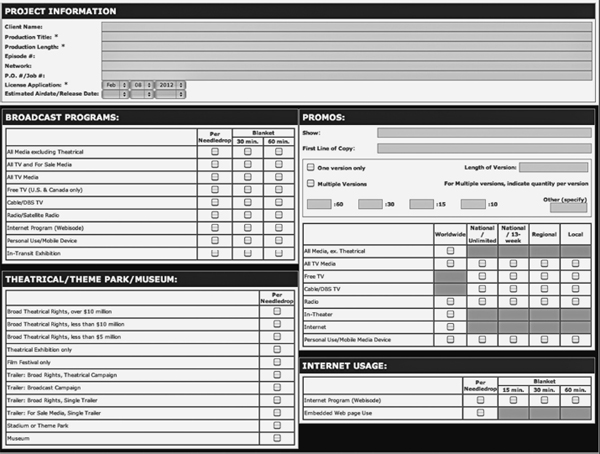

Licensing Cues

Once the final placement of the music is determined and the director approves the cue, the music editor or supervisor completes the process by obtaining the necessary licensing. Most production music companies have online quote request forms to assist the music supervisor in defining the nature of the use (Figure 4.8). It is important to accurately define the extent to which the cue will be used, as this will influence the licensing fee. Licensing parameters can always be expanded at a later time at an additional cost. Once licensing fees are determined, an invoice is issued to the music editor or production company. This invoice constitutes the formal agreement that becomes binding when payment is received.

Figure 4.8 Online Request Form for APM

Workflow for Copy-Protected Music

Overview

Where animation is subjective, arts law is objective, requiring the artist to fully comply with the international laws pertaining to copyright. The digital age has provided consumers with unprecedented access to digital media. The ease and extent to which this content can be acquired has led to a false sense of entitlement by consumers. It is easy for student and independent filmmakers to feel insulated from issues associated with copyright infringement; however, the potential consequences are substantial regardless of the size or nature of the project. It is the role of the music supervisor to clear copy-protected music for use in a film. In Dreamworks’ Shrek films, the music supervisor cleared an average of 14 copy-protected cues per film. This section is designed to provide guidelines for music clearance. As with any legal endeavor, if in doubt, obtain the services of an arts lawyer.

A verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.

Rights Versus License

When seeking to license copy-protected music, it is important to clarify what specific permissions you are requesting from the copyright holder. For scoring purposes, copyright law only applies to melodies and lyrics. Chord progressions, accompaniment figures, and instrumentation are not protected and can be freely used without risk of copyright infringement. Copyright holders have the exclusive right to reproduce, publish, license, or sell their melodies and lyrics. They also have the right to grant permission, set licensing fees, and establish terms for any music synced to picture. A publisher often controls the synchronization rights and the record companies typically hold the master rights.

Every great film composer knows where to steal from.

(Animaniacs)

Synchronization, Master, and Videogram License

There are three specific licenses of primary concern to the music supervisor; the synchronization license, the master license, and the videogram license. The synchronization license is the most important of the three, for if this license is not granted, the music cannot be used on the film in any form. The synchronization license grants the right to sync copy-protected music to moving picture. A synchronization license is granted at the discretion of the copyright owner, who is typically the composer or publisher. To use a specific recording of a song requires a master license, which is often controlled by a record company. To make copies of the film for any form of distribution requires videogram licensing. The videogram license must be obtained by both the publisher and record company if a copy-protected recording is used. Licensing can be time consuming and there are no guarantees. Therefore, it is prudent to begin this process as early as possible.

Public Domain

Works that are public domain can be used freely in an animation. Any music written before January 1, 1923 is public domain. Works written after that date can enter public domain if the term of the copyright expires. Use of the copyright notice (©) became optional on March 1, 1989. It is up to the music supervisor to ensure that a given selection is in fact public domain. One way to establish public domain is to search the selection at www.copyright.gov. Once material is in the public domain, exclusive rights to the work cannot be secured. It is important to differentiate public domain from master rights. Although the music contained on a recording might be public domain, the master rights for the actual recording is usually copy protected.

The authors of the Copyright Act recognized that exceptions involving non-secured permission were necessary to promote the very creativity that the Act was designed to protect. The Copyright Act set forth guidelines governing the use of copy-protected material without securing permission from the copyright holder. These guidelines for nonexclusive rights constitute fair use:

The fair use of a copyrighted work . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, teaching . . . scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether a specific use applies, consider the following:

![]() Is the nature of the use commercial value or educational (demonstrating an acquired skill). Even in educational settings, the use of copy-protected music for the entertainment value does not constitute fair use, even if there are no related financial transactions.

Is the nature of the use commercial value or educational (demonstrating an acquired skill). Even in educational settings, the use of copy-protected music for the entertainment value does not constitute fair use, even if there are no related financial transactions.

![]() The amount and importance of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.

The amount and importance of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.

![]() The effect of the use on the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work. Even if you are not selling the work, distribution, exposure, and unwanted association with a project can have significant impact on the market value of a musical composition.

The effect of the use on the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work. Even if you are not selling the work, distribution, exposure, and unwanted association with a project can have significant impact on the market value of a musical composition.

If an animation complies with these principles, there is strong support for claiming fair use. When claiming fair use, it is still advisable to limit the distribution and exhibition of the work, credit the authors, and display the author’s copyright notice within your work. It is important to keep in mind that fair use is not a law but rather a form of legal defense. With that in mind, it is wise to use it sparingly.

Parody

Parody is an art form that can only exist by using work that is already familiar to the target audience; therefore, provisions had to be made in the Copyright Act for parody or this form of expression would cease to exist. Parody involves the imitation of a recognizable copy-protected work to create a commentary on that work. The commentary does not have to serve academic purposes; it can be for entertainment value. However, both the presentation and the content must be altered or it is not considered a parody. For example, just changing a few words while retaining the same basic meaning does not constitute parody. Parody must be done in a context that does not devalue the original copy-protected work; therefore, parody is most justifiable when the target audience is vastly different than the original. A parody constitutes a new and copyrightable work based on a previously copyrighted work. Because parody involves criticism, copyright owners rarely grant permission to parody. If you ask permission and are denied, you run the additional risk of litigation if you use it anyway. In the United States, fair use can be used successfully to defend parody as long as the primary motive for the parody is artistic expression rather than commercialism. A good example of parody can be heard in the Family Guy “Wasted Talent” episode (2000) featuring “Pure Inebriation,” a parody on “Pure Imagination” from Willie Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971).

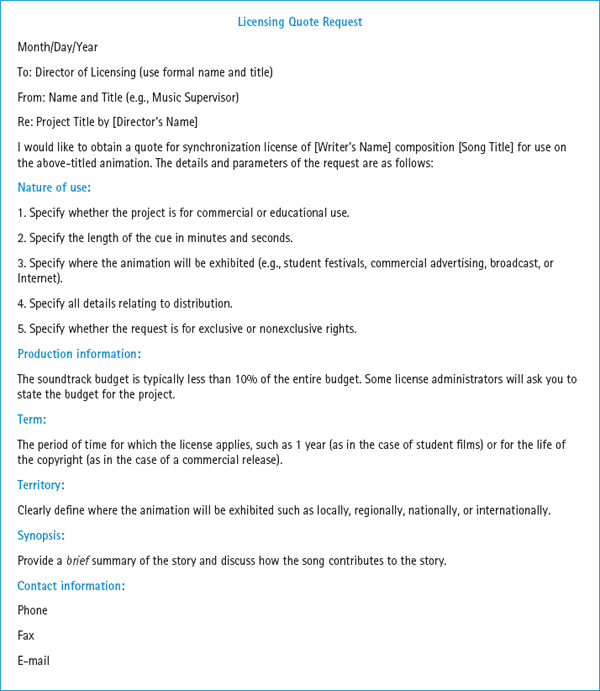

Music Supervision

When requesting any type of licensing, it is important to define the parameters of your request. Because you will likely pay for licensing based on the scope of the request, it is wise to limit the scope to only that which is needed. The following are basic guidelines when requesting a quote for licensing.

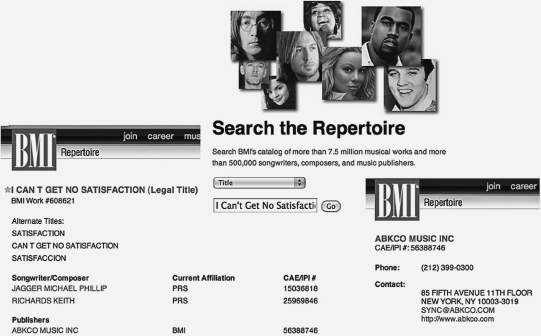

![]() Identify the copyright holder. The publisher usually holds synchronization rights. In most cases, the administrator for this license can be identified through a BMI, ASCAP, or SESAC title search (Figure 4.9). The master rights are often held by the record company.

Identify the copyright holder. The publisher usually holds synchronization rights. In most cases, the administrator for this license can be identified through a BMI, ASCAP, or SESAC title search (Figure 4.9). The master rights are often held by the record company.

![]() Define the territory (e.g., local, regional, national, worldwide, national television, national cable, Internet, film festival). This parameter can be expanded if the film becomes more successful.

Define the territory (e.g., local, regional, national, worldwide, national television, national cable, Internet, film festival). This parameter can be expanded if the film becomes more successful.

![]() Define the term. If you are a student, then your participation in student films typically is limited to 12 months after your graduation date. If you want to have the rights to use the piece forever, you should request “perpetuity for the term.” Remember, the greater the request, the more you can expect to pay and the greater the chance your request will be denied.

Define the term. If you are a student, then your participation in student films typically is limited to 12 months after your graduation date. If you want to have the rights to use the piece forever, you should request “perpetuity for the term.” Remember, the greater the request, the more you can expect to pay and the greater the chance your request will be denied.

![]() Define the nature of use (e.g., broadcast, student festival, distribution, or sale). This information should include the amount of the material to be used (expressed in exact time), where it will be placed in the animation, and the purpose for using it (e.g., narrative lyric quality, emotional amplification, or establishing a time period or location).

Define the nature of use (e.g., broadcast, student festival, distribution, or sale). This information should include the amount of the material to be used (expressed in exact time), where it will be placed in the animation, and the purpose for using it (e.g., narrative lyric quality, emotional amplification, or establishing a time period or location).

![]() When stating the budget for the project, clarify whether the published figure is for the production as a whole or for the music only. The distribution of money varies greatly from project to project. Typically, less than 10 percent of the total film budget is available for scoring.

When stating the budget for the project, clarify whether the published figure is for the production as a whole or for the music only. The distribution of money varies greatly from project to project. Typically, less than 10 percent of the total film budget is available for scoring.

![]() Consider these requests as formal documents read by lawyers and other trained arts management personnel. Use formal language, and proof the final draft for potential errors. Phrase all communication in such a way that places you in the best position to negotiate. Keep in mind that the law demands precision.

Consider these requests as formal documents read by lawyers and other trained arts management personnel. Use formal language, and proof the final draft for potential errors. Phrase all communication in such a way that places you in the best position to negotiate. Keep in mind that the law demands precision.

Historical Trends in Animation Scoring

The Golden Age

In 1928, Walt Disney released his first sound animation, Steamboat Willie, an animated short driven primarily by score. Within a decade, Carl Stalling and Scott Bradley established a unique style of cartoon music through their respective work with Warner Brothers and MGM. This music featured harsh dissonance, rapid changes in tempo, exaggerated performance techniques, and quotations from popular tunes. Stalling and Bradley both had a propensity for hitting the action with music, an approach that would become known as Mickey Mousing. Though Raymond Scott never scored an animation, his music, especially “Powerhouse,” had a profound influence on this musical style and can be heard in many of Carl Stallings scores. Many of the early animations featured wall-to-wall (nonstop) music that functioned as both underscore and SFX. Not all animation of the Golden Age featured this approach to scoring. The early Fleisher animations were dialogue driven and contained fewer sight gags. These animations were scored using a more thematic approach associated with live-action films. Winston Sharples and Sammy Timberg composed or supervised many of these scores for films like Popeye and Superman.

The Television Age

The arrival of television in the late 1940s signaled the end of the Golden Age of animation. As animation migrated to television, decreased budgets and compressed timelines gave rise to a new approach to scoring. Hanna-Barbera emerged as the primary animation studio for this emerging medium. They employed Hoyt Curtain to create the musical style for their episodic animations. As a jingle writer, Curtain had a talent for writing melodic themes with a strong hook. He applied this talent to create some of the most memorable title themes, including The Flintstones, Johnny Quest, and The Jetsons. He also created in-house music libraries used consistently from episode to episode. These libraries accelerated production time, cut costs, and gave the studio a signature sound.

The Animation Renaissance

In 1989, Disney released The Little Mermaid, which featured an original song score by composer Alan Menkin and lyricist Tim Rice. In that same year, Alan Silvestri composed the score for Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Both films were financially successful and renewed studio interest in feature-length animation. In 1995, Pixar released their first feature animation Toy Story, scored by Randy Newman. By the mid-1990s, Alf Clausen had established parody scoring as a familiar element of The Simpsons. Clausen’s skill at parody is well represented in the episode entitled “Two Dozen and One Greyhounds,” which features the song “See My Vest,” a parody of Disney’s “Be Our Guest.” Feature animation continues to emphasize scoring, attracting A-list composers, editors, and supervisors.