The Production Path

Overview

The production path is divided into three phases: preproduction, production, and postproduction. Workflows are developed for each production phase with the aim of optimizing the collective efforts of the production team. The saying “You can have it good, fast, or cheap, but you can only have two of the three” summarizes the forces that influence soundtrack development (Figure 7.1). In practice, “good” costs money, “fast” costs money, and too often there is “no” money. Of the three options, making it good is least negotiable. Therefore, the effective management of resources (time being the greatest) is key to the success of any animated film.

Figure 7.1 Production Triangle

If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.

Preproduction

Overview

Preproduction is the planning and design phase where the story is refined and project logistics are worked out. First time directors are often unsure at what point sound designers and composer are brought into the process. Storyboarding session are an effective opportunity to introduce the supervising sound editor and composer to the project (Figure 7.2). When storyboarding, the animation team acts out individual shots, speaking dialogue in character, and mouthing SFX and humming music. These sessions are often more insightful than the spotting sessions that occur in postproduction. In addition, they provide the sound team with opportunities for creative input, expanding the director’s options as they refine each shot or scene. Through this process, the supervising sound editor and composer develop a budget and production schedule that is integrated into the master budget and schedule.

Figure 7.2 Storyboard for Trip to Granny’s (2001)

Enlisting a Sound Crew

The animation process is at its best when a creative community of collaborators is assembled to work on a project governed by a shared vision. The enlisting of a sound crew can be a daunting task for animators less familiar with sound production. For small independent projects, financial compensation is often limited, and directors must promote intrinsic benefits when enlisting a sound crew. These intrinsic rewards include networking with a community of filmmakers, the opportunity to further develop their specific skill sets, and the opportunity to be associated with a potentially successful film. Directors, new to the process, may be tempted to offer creative license as an additional enticement. However, experienced sound designers and composers prefer that the director be “appropriately” involved in all phases of the soundtrack development. Their time and creative efforts are optimized when the director articulates a clear vision for the soundtrack. When pitching a project, storyboards, scripts, and concept art are often effective tools to generate interest. There are three primary individuals that the animator must enlist to develop a soundtrack. These include the supervising sound editor, the composer, and the re-recording mixer. The supervising sound editor will recruit and head the sound department that develops the dialogue and SFX assets. The composer works independently from sound editorial, heading up a team of music editors, music supervisors, and musicians to produce the score. The re-recording mixer(s) will receive dialogue, music, and FX tracks and shape them into a cohesive mix. There are many supporting roles in each of these departments that were outlined in earlier chapters. If each of the primary roles are properly staffed, the remaining hierarchy will follow and clear lines of communication and workflow will be established.

Developing a Soundtrack Budget

Two elements grow smaller as the production progresses: budgets and schedules. It is important to define these factors and tie them in with any expectations for soundtrack development. Input from the sound designer and composer is critical when developing a budget for audio production, especially in avoiding hidden costs. The sound crew can provide accurate cost estimates and negotiate directly with vendors. Table 7.1 gives a listing of possible expenses incurred in the production of a soundtrack.

Table 7.1 Budget Consideration for Soundtrack Development

| Principal Dialogue, Voice-Over, and ADR | Compare SAG (Screen Actors Guild) rates and online sources when developing an estimate for voice talent. Also consider potential studio rental, equipment rental, and engineering fees, which vary by location. |

| Foley | Most Foley props are acquired as cheaply as possible from garage sales and dumpster diving. In some locations, prop rental companies provide a wide range of hard-to-find props at reasonable rates. There will be additional costs associated with studio rental, the Foley mixer, and the Foley artists. |

| SFX Libraries | Individual SFX can be purchased for specific needs. If a specific library is required, budget approximately $125 per CD. |

| Production Music Cues | Music Licensing. Production libraries are usually more reasonable than copy-protected music that has been commercially released. Licensing fees for small independent projects currently range from $100 to $300 dollars a cue. |

| Synchronization, Master, and Videogram License | These fees are negotiated with the copyright holder. Clearly define the nature of your request to negotiate the lowest fees. Many publishers are licensing songs at no charge for projects, hoping to receive performance royalties instead. |

| Composer or Creative Fees | These fees vary by composer. A creative fee only covers the writing of the cues. Additional cost can occur in producing the cues. |

| Sound Editors | Check the sound editors guild for a current rate guide for union editors. Also check with area recording studios for local mix/editor rates. https://www.editorsguild.com/Wages.cfm |

| Rental Fees | Most sound equipment needed for an animation production can be rented. Even plug-ins are now available for rental. The decision to rent or buy often comes down to availability and production schedules. |

| Backup Drives | It is important to backup your work with at least one level of redundancy. Drives are a cost effective means of securing your media assets. |

Project Management

The animation process involves a multitude of technologies and workflows that must work in tandem. One means of managing an animation project is through the use of a production website (Figure 7.3). There the production team can access concept art, a production calendar, a message board, e-mail links, and a partitioned drive for asset sharing. The production calendar is an important means of sequencing tasks, setting deadlines, and organizing meeting times. Many calendar programs can send automated reminders to the production crew. Most of the media associated with animation is too large to send via email. Presently, there are numerous web-based FTP (file transfer protocol) sites that facilitate file storage and sharing over the Internet. FTP is a client/server protocol that allows clients to log in to a remote server, browse the directories in the server, and upload (send) or download (retrieve) files from the site. As with calendar programs, some FTP sites send automatic messages to the client when new content is added.

A critical and often overlooked aspect of project management is the establishment of production standards. These standards are established in preproduction to facilitate the interchange of media files and to promote synchronization. When properly adhered to, production standards eliminate the need for unnecessary file conversion or transcoding that can potentially degrade the media files. Table 7.2 gives a list of production standards associated with standard definition video. Individual parameters will vary with specific release formats, software requirements, and variations in workflow.

Table 7.2 Audio Standards for Standard Definition Projects

| Production Variables | Industry Standard for NTSC |

| Sample Rate | 48 kHz (minimum) |

| Bit Depth(s) | 16 or 24 bit (24 recommended prior to encoding) |

| File Type(s) | BWF, Aiff, MXF, mp3, AAC |

| Video Wrapper | QuickTime or WMP |

| Video Codec’s | QuickTime, H.264, DV 25 MXF |

| Video Frame Speed | 29.97fps (Once Imported, Pro Tools Frame Speed is fixed and cannot change) |

| Video size and resolution | No Standard (check with Supervising Sound Editor and Re-Recording Mixer) |

| Time code start time for burn in | No Standard (stay consistent throughout production) |

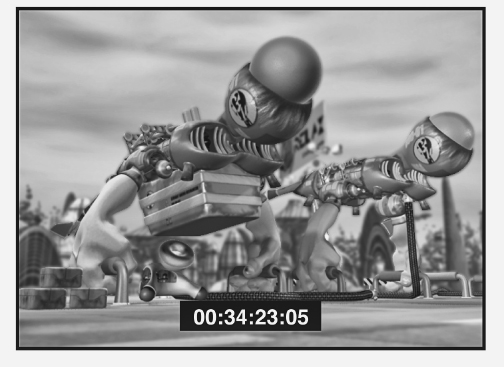

The sound designer and composer will use the time code displayed in the burn-in window to set their session start timing to match (Figure 7.4). The burn-in is also useful to check for monitor latency that can result from converting digital video to NTSC for ADR and Foley sessions. Even though the animation is done at 24 fps, each render to the sound designer should be at 29.97 if releasing in standard definition NTSC. The work print should provide sufficient video resolution while not monopolizing the edit or mix windows.

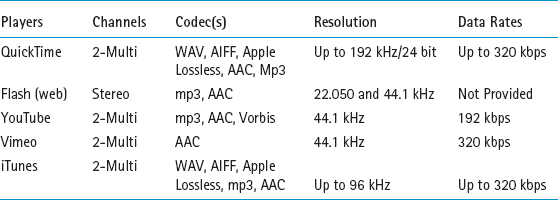

One of the initial decisions made prior to mixing a media project is determining the release format(s). Audio resolution, dynamic range, and available channels vary from format to format. Establishing the project’s release format(s) is an important step toward focusing soundtrack workflow and mix. Today there are a multitude of release formats to consider including theatrical, festival, consumer, online, and personal devices. Theatrical soundtracks are produced and exhibited under the most optimal conditions. The specifications for festival screenings are similar but continue to favor stereo mixes over multi-channel mixes. Consumer formats such as DVD and BluRay can deliver multi-channel audio at high resolutions. Online deliver has become the dominant mode of distribution with QuickTime, Vimeo, YouTube, and iTunes heading the list. Steady improvements in the codecs employed by these online delivery systems have led to increases in quality, limited only by the consumer’s choice of monitors. Tables 7.3 and 7.4 give a listing of release formats and their current audio specifications. These specifications are constantly evolving so it is important to research these options prior to establishing production standards.

Table 7.3 Audio Specifications for Theatrical and Home Theater Release Formats

Table 7.4 Audio Specifications for Computer/Internet Release Formats

*Note that higher data rates require higher bandwidth.

Production

Overview

The production time required to produce each minute of animation is significantly longer than that of live action. This extended schedule can work to the advantage of the sound crew, providing time for ideas to germinate. Though the focus in production is primarily on visuals, there are opportune moments for soundtrack development as well. During the production phase, motion tests are made and multiple versions of the animatic are generated. Motion tests provide an opportunity for sound designers to test their initial design concepts for moving objects. As each new animatic is generated, progressively more detailed movements, gestures, timings, backgrounds, and props are revealed. These added details could be used to refine the temp FX and music. At later stages in production, the animatic is a nearly completed version of the film. Many aspects of the temp effect can be used in the final, blurring the line between production and postproduction.

It is a child’s play deciding what should be done compared with getting it done.

Creating Temp Tracks

Animatics are assembled from storyboards, creating a format where temp FX, music, and scratch dialogue are initially cut. Temp tracks can serve as an important reference for picture editors developing the timings of a track. The animatic is also an important means for script development as the scratch dialogue is evaluated during this stage. It is important (at this stage) to identify any copy-protected music that may influence the animation process (pre-score). By identifying these cues in advance, the music supervisor creates lead-time needed to secure the licensing before the production schedule begins. The 2D animatic is the first and most basic work print consisting of still images that are imported from the storyboard. These stills are gradually replaced with rough animation and preliminary camera work to produce a pre-visualization work print. For the sound designer new to animation, early versions of the animatic can be a bit of a shock. Boxy looking characters float across the floor, arms stretched out and sporting blank facial expressions. This print can be used for initial screenings to demonstrate the soundtrack to the director or test audiences. When the basic animation has been completed, timings are locked and a temporary work print is produced. The final stage of animation production includes compositing, lighting, special effects, rendering, and end-titles. A title sequence (if used) is added at this point in preparation for picture lock. When these elements are combined, the final work print is generated and the postproduction phase begins.

Production Tasks for the Sound and Music Departments

Just as the animatic is a work in progress, so too are the temp tracks. Preliminary work at the production stage promotes creativity, organization, and acquisition. However, it is important to be flexible during production as the timings are still evolving. Animation studios have long recognized the benefits of researching the subject matter in the field; this approach can extend to audio research as well. Designers can explore the physics of how objects move, gain insight into the specific props needed, and experiment with various design approaches. Composers can develop initial themes based on the research of period, ethnic, or stylistic music. The production phase is an ideal time to acquire a specialized SFX library for the project. This library can be developed with original recordings or acquiring commercially. Any work completed during the production phase may potentially be included in the final soundtrack, blurring the distinction between production and postproduction.

If you don’t show up for work on Saturday, don’t bother coming in on Sunday.

Postproduction

Overview

In live action “picture lock” signals the beginning of the formal postproduction phase. In animation, the timing of the animatic is set much earlier, blurring the point in which production ends and postproduction begins. During the spotting session, the director screens the film with the composer and supervising sound editor to map out the specific needs for the soundtrack. At this point, the supervising sound editor may bring on additional crew to meet the remaining production deadlines. Nearly all scoring takes place in post as music cues are timed closely to the picture. Where the production phase is a time to explore ideas, the postproduction phase is the time to commit.

If it weren’t for the last minute, nothing would get done.

Picture lock, or “picture latch” as it is known in sound departments, is an important concept that warrants procedural discussions between the animators and sound editorial. Re-edits of a film are a normal part of the process and both the sound and music departments must be prepared to deal with additional picture changes. However, the setbacks caused by additional picture edits can be minimized if the animator provides an EDL (Edit Decision List) or Change List documenting each change. These lists document the timings of individual edits, and the order in which they were made. Each picture edit is mirrored in the audio editing program. Once the edits are completed, additional audio editing is required to smooth the newly created edit seams. The score is typically most impacted by re-edits due to its linear nature. It is important for the animator to at least consider the possibility that the soundtrack can also be an effective means of developing or fixing a shot that is not working. Picture edits, when improperly handled, slow down the production, rob the designers of creative time, and place a strain on the relationships of the entire production team.

Postproduction Tasks for the Sound and Music Departments

As the animation process nears completion, compositing and effects animation provide additional visual detail that informs the sound design. Table 7.5 shows tasks associated with the postproduction phase.

Table 7.5 Tasks for Postproduction

| ADR (Automated Dialog Replacement) and Additional Voice-Over. | There are several reasons to record additional Voice-Over and ADR near the final stage of the production. These include … |

1.Changes to the script. |

|

2.Availability of new voice talent. |

|

3.The potential for a better interpretation resulting from the increased visual detail available near the final stage. |

|

4.The development of foreign language versions. |

|

| Scoring | A spotting session for score occurs immediately after the picture is locked. After that point, individual cues are written or edited from commercial libraries. |

| Foley | Foley is recorded to provide footsteps, prop, and cloth performances. |

| Creating Design Elements | At this stage, characters, objects, and environments are fully flushed out in both appearance and movement. Design elements are created to represent the characters, objects, and environments that are too specific or imaginative to cut from a library. |

| Sound Editorial | Sound editors clean up tracks, tighten sync, re-conform picture edits, and organize tracks for delivery to the mix stage. |

| Mixing | Mixing is the final process in soundtrack development. This process varies considerably based on the track count and length of the film. The director, supervising sound editor, and music editor should attend the final mix to insure that each stem is properly represented. |

| Layback | Once the mix is completed, the printmaster is delivered to the picture editor for layback. During the layback, the mixer and director screen the film for quality control, checking for level and sync issues. |