Chapter 13. An Architecture for Digital Identity

We’ve all seen cities that don’t quite seem to have a sense of place, where the zoning didn’t yield a coherent set of uses or designs, and things appeared thrown together. This results from a lack of planning. Imagine the difficulty and danger of living in a place where there were few building standards, multiple electrical voltages, and roads were put in place willy-nilly.

This is a situation that most enterprises find themselves in with their digital identity infrastructure. The systems are thrown into place with little thought to standards or interoperability. Solving the problem of the day, week, or month becomes standard operating procedure. The end result is a tangled mess of systems that are brittle and unreliable. Heroic efforts are required to make small changes or even keep the systems running day to day.

In the same way that city planning creates a set of standards and rules for buildings to ensure that neighborhoods are safe and pleasant, an enterprise architecture is a set of standards and rules that creates an interoperable and flexible enterprise-wide IT infrastructure.

The work of city planners provides a model that helps us understand the work required of enterprise architects. This work can be divided into three primary categories :

- Standardization

Dimensioning of pipes, voltage, roadways, etc.

- Certification

Regulated and standardized qualifications for workers

- Management

Rules, notifications, permits, approvals, enforcement, etc.

The tasks in enterprise architecture are largely the same.

If enterprise architectures are like city plans, then system architectures are more like the plans for a single building. The plans for the building are made within the context of the scope of a city plan that not only has defined roads and lots, but also sets standards for sidewalks, setbacks, and so forth. Furthermore, the city plan has adopted building codes that define how the building will be implemented and requires certain best practices.

Enterprise architectures, likewise, define a context for system architectures. Well-defined enterprise architectures make demands on system architectures in order to accomplish specific objectives. Like a good city plan, enterprise architectures also establish procedures that create and maintain the plan and specify the inspection and quality assurance processes that ensure it is followed.

Another aspect of planning is enforcement. There’s no point in creating policies, defining standards, and establishing rules if they’re not enforced. Enforcement can be a cause for contention within an organization. Furthermore, it’s not free. Just as the builder (and ultimately the homeowner) pays the cost for inspections and compliance, system architectures that live within the context of an enterprise architecture will also pay a price, both implicit and explicit. Conforming to the enterprise architecture will be neither convenient nor cheap, and business units will push back if they don’t understand the payoff.

Identity Management Architecture

Your organization may already be deeply involved in building enterprise architectures, or the concept may be new to you. Either way, the concepts of enterprise architecture can be helpful in planning and carrying out an identity management strategy within your organization. Whether or not you’re developing enterprise architectures, this book will show you how you can use the ideas and methodology involved in creating one for developing comprehensive plans, processes, and infrastructure for identity management. I call this an identity management architecture (IMA).

I’m using identity management architecture in the same sense that I’ve described enterprise architecture. An IMA is a coherent set of standards, policies, certifications, and management activities. These are aimed at providing a context for implementing a digital identity infrastructure that meets the current goals and objectives of the business, and is capable of evolving to meet future goals and objectives.

Most of the topics we associate with digital identity have traditionally been part of an organization’s security planning. By now, I hope you’re convinced that proactively managing identity goes beyond the traditional security aspects of authentication and authorization. Similarly, identity management architectures differ from typical information security planning in several important respects:

Identity management requires a functional business model. Information security planning rarely makes mention of the business. This business model describes in some detail how the business functions. This includes identifying important entities, resources, and processes and their relationships. The functional business model may be detailed or abstract depending on the depth of the IMA planning process.

An identity management strategy is driven by long-term business goals surrounding employees, partners, suppliers, and customers, whereas security planning usually reacts to these relationships as perturbations or exceptions to the plan. I rarely talk to a business executive who doesn’t complain about business goals being at the mercy of security planning.

Identity management requires that resources and entities be identified first. Typical information security plans are largely about perimeter defenses. Consequently, they are usually concerned with networks and servers rather than business documents and customers. Like the functional business model, the level of detail in the inventory of resources and entities varies depending on the nature of the IMA planning process, but these are its central focus.

An IMA identifies dependencies between identity data and systems. These dependencies are used to determine implementation priorities. Security planning, and most IT planning for that matter, often emphasizes projects that are deemed critical without seriously considering dependencies between data and systems. An IMA highlights those dependencies so that they can be used in the planning process.

IMAs provide business justification for security and directory infrastructures that go beyond perimeter security to enable valuable business activities. At its heart, an IMA is a set of plans, policies, and procedures whose most significant contribution to the bottom line will be through the improvements it makes to future system designs and implementations.

The Benefits of an Identity Management Architecture

An IMA provides a number of benefits to the business. One of the biggest is allowing the organization to focus on the positive aspects of digital identity in creating value. The traditional approach to security has focused on keeping the bad guys out, often at the expense of getting the job done. Identity management architectures focus on creating a digital identity infrastructure that gets employees, customers, partners, and suppliers to the resources they need.

At the same time, another important benefit is increased information security. This might seem like a contradiction, but I contend that by removing the crutch of perimeter defense and creating a comprehensive plan for managing identity and access control, security is improved. Security experts have preached for years that proper system implementation is a more reliable means of creating security than doing it as an afterthought. Identity management architectures are the road to that goal.

Increased security does not have to come at the cost of user convenience. In fact, the opposite is true. A properly implemented digital identity infrastructure allows information to flow more freely, while keeping it within the bounds set by the digital identity management policy. IMAs allow the organization to loosen the restrictions surrounding information management while gaining greater control of information access.

An IMA creates a plan that allows features such as single sign-on and federated identity management to work reliably. This significantly reduces the burden on employees, customers, partners, and suppliers who interface with the organization.

Part of creating an IMA is to design a management process for the enterprise’s identity records. Many enterprises don’t know what information they have and which entities regularly access it. An IMA contains inventories and structural information for identity stores and records. Furthermore, the architecture documents their relationships to one another and to the business processes they enable. These results alone can provide significant value to enterprise planners.

Most organizations don’t know what costs they incur in managing identity. Creating an IMA not only sheds light on those costs, but can also reduce them. Reduced help desk costs alone can provide a significant return on investment to enterprises that take even simple steps.

Almost every enterprise contends with external requirements from partners and government regulators. In some industries, these external requirements can be quite severe (banking, health, insurance, and securities come to mind). Many of these external requirements have to do with controlling information flow and access. Often, organizations go to heroic lengths to meet these requirements, and the sad truth is that they usually fall short. IMAs provide a comprehensive plan that can take these requirements into account and ensure that systems built in the enterprise meet these requirements.

An IMA creates a plan for more closely managing information assets and controlling access. Specifically, critical assets are identified and policies put in place to protect them. The infrastructure is built so that these policies are more easily enforced. All of this reduces the chance of losing critical information from either malicious or negligent behavior.

Because the IMA is focused on the needs of the business, management participation provides a business perspective to what were previously internal IT processes. Security has traditionally been the sole purview of the IT department. Business units were just expected to live with it, regardless of inconvenience and lost opportunities. The irony is that the business is the reason for the security in the first place. Perimeter defense has to be very strong and very tight to be effective, but it’s a one-size-fits-all solution. An IMA starts with a business model and relies on the ongoing participation of business managers to avoid these disconnects.

Having an IMA creates a more agile enterprise that easily accommodates changes caused by new business strategies, new products, new markets, and mergers and acquisitions. An IMA provides a blueprint for how the business manages information assets. This blueprint and the infrastructure it depicts provide a neat and easily understood system that is more flexible than the typical hodge-podge collection of identity systems that have grown up over the years. The IMA clearly outlines the policies and standards that are in place and documents the overall system design. This provides clear guidelines for integrating new systems into the legacy infrastructure.

An IMA is founded upon a clear governance process that has been agreed to by all players in the enterprise. This process guides the development of the architecture and its maintenance through the years. This governance process has uses beyond identity management, and can be exploited by the CIO and executive managers to guide other enterprise projects as well.

An IMA includes business models that are used to ensure that the identity infrastructure is aligned with what the business needs. These models are useful beyond building the infrastructure, and can form the basis for designing and building other IT systems that are aligned with business needs. As a consequence, creating an IMA leads to increased understanding of the business.

Success Factors

Success in developing an IMA depends on a number of factors:

Executive management is aware of the need for identity management, recognizes the benefit that will accrue to the organization, and has accepted their roles and responsibilities.

Resources have been committed to developing the architecture.

The IT personnel in the organization, regardless of how they are organized, understand and accept the need for coordinated identity management.

A governance process for determining roles and responsibilities, creating policy, and enforcing it has been put in place and is functioning.

All players, including business managers, have realistic expectations of short-term costs and benefits.

There is a culture in the enterprise that is forward-looking, accepting of change, and willing to endure some risk.

You may look at the list and decide that such an ideal enterprise doesn’t exist. You’re probably right. Even so, I’ve tried to keep the list realistic. By building a case for identity management, you can change some of these factors. In the coming chapters, as we discuss the steps you should take in creating your own IMA, you’ll see that part of the process is building support and obtaining the resources necessary to ensure the success of the project as well as setting realistic expectations.

The final success factor, culture, may be out of your control, and changing it can be a job far larger than the one addressed in this book. If the culture is wrong, you may need to approach identity management far less holistically than the approach proffered here.

Roadblocks

Many organizations will fail in their efforts to create an IMA. The following is a partial list of roadblocks that might thwart your attempts in your enterprise.

- Mistrust

This is a significant problem in many enterprises. Years of poorly managed projects and expectations may have left business units with antipathy or even hostility toward the IT organization. IT organizations, being made up of human beings, respond in kind. The end result is a dysfunctional situation that sinks any proposal from IT.

You will need to decide whether the process for creating an IMA is one that will help mend that rift or whether other, more fundamental steps need to be taken first.

- Fear of loss of control

This fear is often expressed as something else, such as lack of support. IT organizations may fear that they are giving up control of decisions they’ve always made (like those surrounding security) to business units.

Business units may fear giving up their data. For example, if HR has always maintained the employee database and you start talking about creating a metadirectory where multiple players will have access to or, heaven forbid, the ability to change employee data, you’re likely to get significant push back.

Part of the process of creating an IMA is aimed directly at giving everyone a voice and being able to work through these fears. The process should be targeted at creating consensus around key principles regarding identity processes and data, and how they’re managed.

- Inexperience or lack of training

Being successful requires that everyone understand each other and have a common vocabulary. Beyond that, and perhaps more importantly, each player in building the IMA must have a common set of goals and ideas surrounding what the organization is trying to achieve. The coming chapters addresses these problems.

- Compulsion to over plan or find the “best” methodology

“Paralysis by analysis” is perhaps a cliché, but it is nonetheless a very real phenomenon. The roadmap presented in this book offers ample opportunity to get caught up in the process and to cycle over and over on certain points, searching for the perfect process or 100% consensus. Equally deadly is the belief by some organizations and people that success is a product of the methodology, rather than the people and their goals. The process presented here offers considerable room for creating and refining process and methodology. Some organizations get lost in creating the process and never get around to implementing it.

The solution to both these problems is twofold. First, you should have a completion goal set by a high-level executive, the CIO or perhaps even the CEO. Second, the leader of the IMA process must be strong and driven to completing it. At the same time, the leader should be sensitive to fact that the process is designed to bring people to a common understanding about how identity is managed and therefore takes time.

- Severe, chronic resource shortages

If your IT organization can’t seem to finish projects, has far too many critical projects for the available resources, or has a significant backlog of critical projects, then this should raise a red flag. Finishing the IMA and bringing the identity infrastructure into compliance will be impossible under these circumstances. The IMA will be looked on as one more project, piled onto the already overwhelming burden. Equally important, the business units will not likely see the architecture as a realistic project and consequently not give it the attention and resources that it requires.

The best plan in this circumstance is to attack the more significant project-planning problem head-on and return to identity management once more pressing problems are in hand.

- Arrogance on the part of the IT organization—the “we know best” mentality

Let’s face it—IT organizations are filled with people who think they know the answer to every problem. I’ve often joked that programmers and system people are even more inclined than lawyers to thinking they can do anything. Part of the reason for this mentality is that they are, in fact, usually quite bright, and their positions often insulate them from the messy realities of customers and making a profit. This is a blessing and a handicap. The blessing is that they are a source for good ideas and innovative thinking. The handicap is that they frequently express their ideas with less tact than you’d like, and they can decide that they’ll force things to happen their way regardless of what people in the business units think.

The process of creating an IMA can help alleviate this problem, as it brings some of these IT people into close and frequent contact with their customers in the business units. Make sure that the thought leaders in your IT organization are part of the process so that they can help convince others of the value of an IMA. Also, be prepared to take appropriate personnel action against those who repeatedly torpedo the process.

- Corporate politics and players with other motivations

This is a roadblock that you will have to deal with as it comes up. Unfortunately, you may not understand the motivations of others who fight against you well enough to effectively counter the problems.

The most effective solution is to try to understand the motivations and see if there’s some way to reach a compromise. I’ve been in situations where I never could understand the rationale behind the motivations of others, and no amount of talking led me to a situation that we could both live with. In those cases, the only thing to fall back on is the commitment of executive leadership to the process. This stresses the need to pay close attention to receiving that support and commitment as conspicuously and unambiguously as possible.

- Fixation on short-term return on investment (ROI)

Many leaders in IT organizations and business units are overly concerned with short term ROI. That’s not to say that ROI is unimportant or that it can be ignored in creating an IMA. Even so, a review of the benefits from the previous section will affirm that many of them are not directly monetary. The benefits from an IMA are not predominantly returned as immediate savings, but as the long-term enablement of new business processes and models.

Be sure not to oversell an IMA as a solution to problems that it will not solve. Be realistic. If executive management can’t be convinced by the real benefits, properly explained, then your organization probably isn’t ready for an IMA.

- Acceptance of the status quo

Some people like how things are and don’t have a significant motivation to change them. Overcoming this roadblock will probably require a long and careful campaign to show why the status quo is not as rosy as everyone thinks and to paint a vision for what might be. Don’t underestimate the length of time it will likely take to overcome unrealistic satisfaction.

- Recent visible failure at IT planning

If your organization has recently attempted a large IT planning exercise that failed, particularly one where the business units were heavily involved, the IMA process will be met with stiff resistance.

This is one problem that only time and several small and medium successes will overcome. A scaled-down process may be a route you can take.

Identity Management Architecture Components

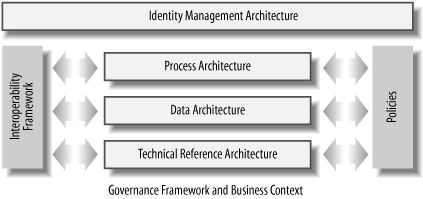

Building an IMA involves creating a series of interrelated components . Figure 13-1 shows a schematic diagram of these components.

The IMA is created within a governance framework that lays the ground rules and a business context that lays out long-term business goals, principles, and objectives. Chapter 14 will outline how you can build a governance framework for your organization. Chapter 14 will also show you how to understand and document the business context.

The process architecture determines how your business accomplishes identity tasks now and how they should be accomplished. Identity processes are evaluated and improved using a maturity model for identity management that gives clear direction on how processes should be changed to improve your identity infrastructure.

Chapter 15 will discuss the identity management maturity model and show how to use it in your organization.

The data architecture is a model of the identity data in your organization. Building an identity data architecture involves determining what data you have and then standardizing data practices in three important areas: categorizing, exchanging, and structuring data. Chapter 16 will discuss this process.

Identity policies are a crucial way for your organization to set direction, communicate standards, and create an environment in which interoperable systems can be designed and built. An identity interoperability framework is a set of standards that your organization has committed to using. These two pieces form the backbone of the IMA, and are informed by and used by the other components. Chapter 17 and 18 discuss interoperability framework and identity policies, respectively.

The technical reference architecture provides implementation guidance to system architects. Reference architectures tell system architects how to create systems that work with the enterprise identity infrastructure and with each other. Chapter 19 will discuss reference architectures and show you how to build one.

Finally, Chapter 20 will summarize the process and provide timelines showing how these various pieces are sequenced.

Conclusion

Our goal in laying out the process for building the IMA is to create a system that is agile and readily adapts to changing business needs. The key to making that happen is the governance framework, so that’s where we’ll start.