Chapter 20. Building an Identity Management Architecture

The last seven chapters have discussed the importance of building an IMA and how to go about constructing each of the components. In this chapter, we’ll discuss how to put it all together.

Scoping the Process

Scope is a critical decision in creating a process that works. In this book, we’ve used enterprise to refer to the organization building the IMA. As I said in the Preface, when I talk about “the enterprise,” I’m referring to any mostly independent organization. Companies, government agencies, and NGOs (non-governmental organizations, such as the American Red Cross) all qualify. Even divisions within those organizations may qualify as an enterprise under this definition. The key test is whether or not you can imagine the organization developing its own digital identity strategy. So, an independent business unit probably qualifies, but the marketing department in that business unit doesn’t, because its identity strategy can’t be independent of the other departments with which it interacts.

As we’ve seen, the goal of an IMA process is to create the context within which a digital identity infrastructure can be implemented. If that infrastructure is to support the constant use and interoperability of identity data throughout the organization, then “enterprise” needs to be defined quite broadly to include every suborganization along with all their processes, identity data, and systems as well.

On the other hand, an enterprise-wide scope for the IMA effort may be overly ambitious as a starting place. Instead, you should lay out a logical progression of ever increasing areas of inclusion for the IMA process until eventually this all-encompassing scope is reached.

Which Projects Are Enterprise Projects?

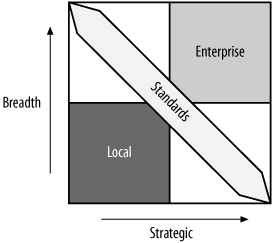

Another question that IT departments frequently wrestle with is which projects and systems should be enterprise projects , built and operated for the good of multiple business units, and which are better built and operated by the business units themselves. Figure 20-1 shows a decision matrix I’ve found helpful for determining what activities and projects fall under the “enterprise” umbrella.

The two axes in Figure 20-1 are strategic importance and the scope of an activity or project. Activities and projects farther along the horizontal axis more directly support the strategic goals of the organization, and activities and projects farther along the vertical axis are used by or affect more and more of the organization. Here are a few examples:

A financial control system that is internal to the finance department, but directly supports the CEO’s goal to curb capital spending, would place high on the “strategic importance” axis and low on the “breadth” axis.

A directory project that supports an online directory of employees and eases creation of the company phone book would be placed high on the “breadth” axis, but may score low in strategic importance.

A project to implement a new customer relationship management (CRM) system would place high on both the “breadth” and “strategic” axes.

The upper-right quadrant represents activities and projects that are clearly enterprise projects. They are strategically important and affect many divisions within the organization. These activities and projects should fall under the purview of the IMA effort and are likely candidates to be planned, implemented, and maintained by the enterprise IT organization.

The lower-left quadrant, by contrast, is populated by activities and projects that are neither strategic nor large in scope. Most of these activities and project never rise to the notice of the enterprise IT group and affect very few departments. All of the spreadsheets that people create every day in support of their jobs are good examples of the extreme case. They are very tactical and support only a single person or a small group.

The band across the middle of the figure illustrates a strategy for dealing with projects that are on the borderline. The goal of an IMA is to create an environment for interoperability. Many of the projects in the upper-left and lower-right quadrants will not be conducted by the enterprise IT group, but rather by a business unit. Still, with the proper standards, policies, and procedures in place, their work should interoperate with the digital identity infrastructure that results from the IMA. Reference architectures play a critical role in supporting the interoperability of business unit-sponsored projects.

Sequencing the IMA Effort

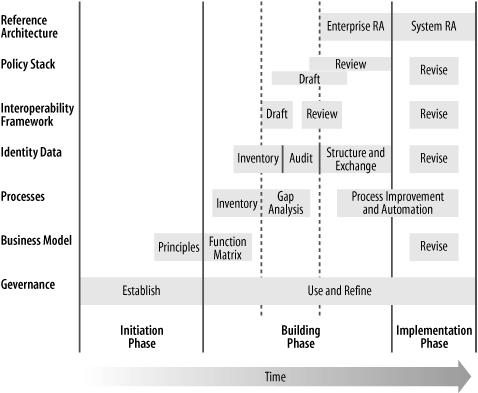

We’ve spent a great deal of time talking about the individual components of the IMA, but you may be wondering about sequencing the various steps. Figure 20-2 shows the phases in building an IMA and when each of the components comes into play. I’ve divided the effort into three primary phases: the initiation phase, the building phase, and the implementation phase.

The initiation phase is when the vision for the IMA is created and the governance process is put into place. Business principles are determined at the end of this phase. The initiation phase may take a great deal of time, depending on how hard it is to create the vision for identity management in your organization.

The building phase is when most of the work gets done. The business function matrix and process inventory are created first. They overlap because as business functions are determined, some process inventory work can be started. For a large organization, this overlap might be significant. A small organization will find that the function matrix must be completed entirely before the process inventory can begin.

As the process inventory is completed and the gap analysis begins, the data inventory can be done in parallel. Remember that these two activities are complementary and may require some iteration. With the process inventory complete, the first draft of the interoperability framework (IF) can be written. This in turn allows policies to be written. Notice that drafting and reviewing policies overlap, because there are a number of them and the review of one policy can be done while another is in the drafting stage. The diagram does not show the iterative nature of the review and drafting activities.

During the final part of the building phase, the reference architecture can be completed, based on the process inventory, identity data inventory, and IF. The data structure and exchange standards can be created at this time. Also, the organization can begin to automate and improve processes as necessary.

The implementation phase is when the IMA lifecycle shown in Figure 14-1 comes into play as the components built in the second phase are used and revised.

A Piece at a Time

The IMA isn’t something you build once and then simply use; it’s a constantly evolving collection of information, policies, and processes. Consequently, you may find it helpful to think of creating a roadmap or timeline for the process. The roadmap looks like Figure 20-2, but turned into a project plan that repeats steps as necessary to include more and more of the of the enterprise. The roadmap will specify what the scope of the process is now and in the future. A roadmap keeps the process from trying to boil the ocean while at the same time, assuring the enterprise that important issues will eventually be dealt with. The roadmap is the high-level plan for applying the IMA process to the enterprise.

You will be tempted to split the task along organizational boundaries. This is a mistake if your organization is split into functional units such as sales and marketing, engineering, and human resources. Each of these functional departments depends on other departments and interacts with them to a large degree. Consequently, a large amount of identity information is likely being transferred in and out of these departments. Furthermore, any one department is unlikely to have a complete picture of the needed identity information and infrastructure. Thus, an IMA process for the identity functions in the human resources department, for example, will be incomplete and in danger of making assumptions that have to be radically altered in future phases on the roadmap.

A better choice is to pick a division or subsidiary that includes most of its own business functions. Such a unit will have control over its systems and the services it offers to customers as well as the bottom line from those services. Consequently, there is strong motivation to complete the IMA process and reap the benefits as well as sufficient control to ensure success.

Of course, life is never as simple as the theory espoused in a book. For example, the State of Utah had over 25 individual departments, which could have been seen as relatively self-contained business units. Any one of them would be a good environment in which to create an IMA process. The exception was that centralized HR and finance functions served every department. In this kind of hybrid organization, an IMA roadmap would have to address issues in the HR and finance departments at the same time that the IMA process was being applied in one or more business units. Every situation is different, and some creativity will need to be employed to slice the problem up into tractable chunks and lay them out on a roadmap.

An important dimension in the roadmap will be to cover what I call products and projects. I use the term product to denote all of the customer-facing services that the enterprise offers, even if they may not be for sale in the traditional sense. The enterprise portal is a good example of a product that almost every organization has. Ensure that the IMA roadmap includes not just IT projects for internal systems, but also includes products, online or offline, that have an identity component. This may be as simple as considering the customer relationship management (CRM) system in the roadmap at appropriate times. On the other hand, there may be numerous online projects that gather and use identity information independent of the CRM system. Be sure they’re included in the process.

As you build the roadmap, it is important to consider the favorable and unfavorable characteristics of the organizations. Some parts of the organization may not be amenable to IMA at the present time because of one or more problems. After considering the characteristics of the business units, there should be some clear candidates for building an IMA. Pick the easy wins and get some early successes for the process. At the same time, the roadmap should include steps for dealing with unfavorable characteristics in the enterprise and mitigate them in parallel with the ongoing IMA process.

The creation of a roadmap will help alleviate fears in the organization that some parts are being left behind. Recognize that the roadmap is not a static document, but part of the overall IMA lifecycle shown in Figure 14-1 and, as such, is subject to constant review and update as the IMA process proceeds.

Conclusion: Dispelling IMA Myths

I hope that this book has given you evidence of the benefits of proactively managing identity, information about the technologies available for doing so, and a methodology for building an interoperable identity infrastructure in your organization. Still, as you contemplate the work involved in creating an IMA for your organization, you may have some concern that it can really work. If so, you may still believe some of the myths about digital identity and enterprise planning.

The first myth goes something like, “This is great for a smaller organization, but we’re too complex for this level of planning.” The truth is, the more complex you are, the more you have to rely on interoperability to get strategic value out of identity. Without interoperable systems, you’ll find that even the smallest of tasks become huge projects, because they have to be fit into the ad hoc infrastructure that has grown up. Fight this myth by creating a vision and piloting the IMA in a self-contained business unit.

The second myth is just the opposite: “This is great for a larger organization, but we don’t have the staff or time to manage this effort.” The IMA process can be adapted to even the smallest of organizations. This book has described a process that can be scaled to fit most situations. In small organizations, the IMA effort is made easy by the fact that there are usually a few recognized decision makers and the group arrives at consensus fairly easily because of shared goals. You may already have a good handle on process and identity data, so start with an interoperability framework and some baseline policies. Build a reference architecture and follow it. This will provide a good foundation as your business grows.

The third myth is a variation on the second: “An IMA is great for an organization that has a tradition of planning, but we’ve always prided ourselves on being nimble.” In fact, most organizations that can say this with a straight face do plan, they just don’t recognize it as such. The prescription is largely the same as the last myth: don’t build a straightjacket. Make the governance process fit your traditions, but set standards and policies to guide system development.

The fourth myth says, “We’ll spend all our time planning and none of it executing.” This myth misses the point that the IMA should be built to fit the organization and its needs. Pick the places in your organization where having good identity infrastructure would make the most difference. Engage in an IMA process for that piece and then repeat on the next priority. Whatever you do, do something.

The last myth is common in many IT shops: “Interoperability is about buying (or building) the right technology.” Many technologists wish this were true and act as if it were. The result is a litany of failed projects that never meet their goals, because they missed the important governance and modeling steps necessary for success. Smart CIOs and IT managers know that good IT is much more than buying the right product.

You’ll probably hear other objections as you move forward. Listen to them and tackle them head on. The important thing is to adapt the ideas in this book to your organization while never losing site of the goal: a flexible and interoperable identity infrastructure. Remember that flexibility and interoperability are products of an environment that guides decision making. Create that environment, and you’ll get an identity infrastructure that works for your business.