Chapter 14. Governance and Business Modeling

When I became CIO for the State of Utah, I had very little appreciation for how much time and effort went into governance issues in a large organization. Before my stint as CIO, I’d been CTO of http://iMall.com, a company I founded; I had hired nearly everyone who worked for me. As we’d built the organization, we’d also built and shaped the vision and the culture. People naturally understood the business, because they’d seen it develop and had crucial roles in making it work. Furthermore, while we’d had our share of culture problems, we’d handled them on the fly and with decisiveness. When decisions needed to be made, we made them, and things worked marvelously.

I soon found out that the state was a different animal altogether. There were, of course, differences between the public and private sectors, but over and above those, the organization was an order of magnitude larger than what I was used to, and there was what I call “legacy lethargy.” Moreover, IT was organized in a decentralized fashion so that no one really had the authority to make important decisions, even when there was clear and imminent risk.

For example, at one point, for a period of about two months, a wireless network was set up in the capitol with no access control whatsoever. Anyone with a laptop and wireless card could come to the capitol and surf the Net at taxpayers’ expense. What was worse was that the network had been set up for legislators, so it was possible to monitor network traffic between legislative laptops. I knew about it almost from the beginning, and yet, I was powerless to put an end to it. The network had been put in place by another organization, and even though it presented a clear risk—not just to the people who used it, but to the entire enterprise network—there was no process in place to review plans, audit compliance with policy, or take corrective action. In short, we were stuck by our lack of a governance process.

Governance issues seemed to take up almost all my time when I was CIO. The governor had a clear vision for what he wanted IT to accomplish, but it was difficult to see how to move the organization toward those goals. Part of the problem was a lack of understanding on my part of how to use the organizational tools I had, because they were different than the tools I was used to. Part of the problem was that we needed some new tools and, most important, an enterprise-wide vision and commitment to achieving the goals of the chief executive.

After months of frustration, we finally embarked on a process to create that vision in a large cohort of the executive management, both business and IT. We were also to determine the process by which we’d govern the implementation of that vision. Those meetings, which I’d now call the “architecture initiation phase,” lasted over a three-month period and involved over a hundred people in dozens of meetings. It was exhausting. Nearly everyone grumbled, including me. I wanted to build things, not spend all my time in meetings, and so did they. I’ve come to understand, however, how important that process is when creating enterprise-wide vision, designs, services, and systems.

In the end, we created a governance process that, looking back, had many of the required features of a good governance model but, for many reasons, failed to take hold. The process was a step forward, but it ultimately suffered from three things:

The resulting governance process was incomplete. There were crucial functions, such as auditing, that received very little attention, in part, because they were unpopular.

The model lacked a clear financial structure. IT governance, like city planning, isn’t free, and resources need to be committed unambiguously for it to work.

There was insufficient buy-off by many of the people whose support was critical to the process. We should have spent even more time in meetings building consensus and communicating the vision and plans.

We could have mitigated these problems, had we had a better idea about what the initiation phase had to accomplish in order for it to succeed. At the time, I couldn’t see the forest for the trees; I was too caught up in immediate goals and meetings to understand the true nature of what we had to accomplish. Looking back, I have a clearer view and can see the pitfalls and have tried to help others avoid them.

You may share my initial lack of appreciation for governance and wonder why you’re reading about it in a book on digital identity. You may be itching to get to the business of building a digital identity infrastructure and be tempted to just skip all this political stuff and get to the meat. I hope the preceding story will help you overcome that temptation, and you’ll spend some time understanding the governance process, along with the modeling and planning work that follows.

IMA Lifecycle

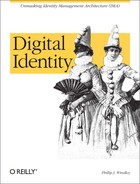

Before we get too far into discussing the IMA governance process, we should spend some time discussing the IMA lifecycle . Figure 14-1 shows that lifecycle, in general terms. The first thing to note is that a lifecycle implies a continuing process, and that’s exactly what we’re hoping for. The IMA should be an ever-evolving architecture that reflects current business needs. The IMA lifecycle is an up front acknowledgment that the IMA will affect the business on which it is built. As the IMA is built and put into practice, the business will change. The lifecycle feeds those changes back into the architecture to create a dynamic process.

The cycle starts with modeling, by which we mean the process of understanding the business, data, application, and technology environments within which the identity infrastructure will exist. We will spend a great deal of time in later chapters discussing the modeling aspects of identity management architectures. Modeling is not just where we start, but where we return, time and again, to gage the vitality of the IMA and monitor the ever-changing environment.

The second phase in the lifecycle consists of planning and documenting. This is an important activity that takes the models built in the first phase into account and creates plans for meeting the identity needs of the organization. This is the phase where standards are defined or set forth, certification requirements are laid out, and policies are created and discussed.

In the third phase of the lifecycle, the plans, policies, standards, and so on that were created in the second phase are reviewed. There might be several iterations back through the modeling or planning activities before they are finally approved. Once they are, the plans and policy are considered in force and, in a healthy organization, should be considered binding.

The next phase of the lifecycle is labeled communicate. You should not interpret this to mean that the other phases are carried out in secret, and this is the first time that others in the organization are informed of what’s happening. To the contrary, we’ll see that the entire process is designed to involve as many people and communicate the happenings as broadly as possible, even gaining consensus around important ideas before they are approved.

However, after the plans of the second phase have been approved in the third phase, they need to be communicated as approved plans and be maintained in a way that they serve as a reference for others in the organization who used them in their work. This implies more than simply sending them out in an email and hoping that everyone keeps the most recent copy. The communication phase requires version control, authoritative storage and presentation, easy reference, and searching.

The IMA is used in the implementation phase by system architects and others in the organization. The IMA should affect what is bought, how systems are built, and how data is stored and used.

The final phase of the IMA lifecycle is one that is often overlooked, but plays a crucial role in turning what would otherwise be a dead-end planning exercise into a living, cyclic process: auditing. Auditing is, perhaps, an unfortunate name, because no one wants to be audited. Even so, the feedback that the organization gets from comparing the plans to the implementation and then suggesting changes is invaluable. Just the number of outflows from the auditing box should be a clue to its importance. The audit might suggest changes to implementations to bring them into compliance with established plans. Alternately, the audit might suggest changes to the plans themselves, because they are unworkable in certain situations or not accomplishing their goals. Lastly, the audit might suggest changes to the models based on an evaluation of existing conditions.

IMA Governance Model

Creating an IMA requires the help and cooperation of multiple people from many different organizations within the enterprise. In order to coordinate their actions and create an atmosphere where the results will be accepted and used, the process for creating the IMA, approving it, and enforcing its provisions, must be clearly delineated.

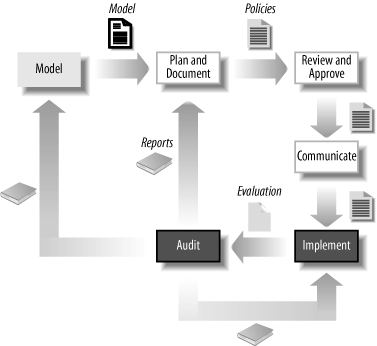

Figure 14-2 shows a sample governance model for creating an IMA. This figure does not show a new organization, but rather a relationship between roles that will be assumed by people already in the organization. We’ll see how these roles interact in detail in this chapter.

The governance model presented here is certainly not the only one that will work, and it will need to be tailored to your organization. The objectives of the model are the following:

Create the identity management architecture.

Ensure that every organization in the enterprise that will be affected by the IMA has an opportunity to participate in its creation.

Yield a result consistent with the strategic goals of the organization.

Yield a result that will drive the goals and tactical implementation plans of all organizations within the enterprise as they relate to identity.

As you read the following description of roles and processes, keep these objectives in mind. That will help you determine how best to map this model onto your own organization.

At first, the information that follows may seem like overkill. The temptation will be strong to just get a few trusted people together and tell them to determine a strategy and then sell, or even announce, the new strategy to the rest of the organization. In some organizations, it may even work. Before you do that, carefully read and understand this chapter. I think you’ll find that it’s not as complicated as it appears at first, and the various roles and procedures serve useful purposes that are worthwhile.

Initial Steps

You can take specific steps in the initiation phase to help ensure a successful outcome of your IMA process:

Develop a vision of IMA effort, and gain executive support from both IT and business units.

Determine appropriate governance roles and responsibilities, and determine who will fill these roles.

Determine the initial scope of the IMA work, and lay out a roadmap for future efforts.

Obtain a commitment for funding the IMA effort.

The following sections describe these steps in more detail.

Creating a Vision

The first step in the initiation phase is to create a vision for what the IMA will accomplish within the organization. Creating the vision requires more than simply writing the vision down, although that’s certainly necessary. Creating a vision is a collective effort among the people who will have to buy off on and participate in the IMA activity.

The first step in creating the vision is for the enterprise leader (perhaps the CEO or the CIO) to establish the need for the IMA and to issue a challenge to the organization to create one. The challenge should spell out, in high-level terms, the objectives that the IMA activity is meant to accomplish. For example, the objectives might be:

Protecting critical business information assets through the proper use of digital identity

Enabling business interactions with partners and suppliers

Understanding our customers better

Supporting safe access to critical information and processes by customers, employees, suppliers, and partners

Building a digital identity infrastructure that is flexible and agile

These objectives should be placed in a charter that is communicated widely within the enterprise, both to business and IT units.

After communicating the charter, the next task is to develop a “straw-man” vision that describes a target digital identity infrastructure fulfilling business goals and objectives in a generic way. The following are specific steps you can take to help create the straw-man vision:

Assemble background information on the business units, lines of business, its customers, partners, suppliers, objectives, people, and so on. This information can come from many sources including site visits, interviews, written reports, position papers, memos, and product literature.

Determine the business goals and objectives of business unit leadership, and identify identity issues buried within those goals and objectives.

Visit other organizations that are further along the path to creating an IMA and already have a working digital identity infrastructure.

Prepare presentations using the information gleaned in previous steps and the straw-man vision to present to key business executives within the organization.

Meet with key business leaders to ensure that your understanding of the business goals is correct and to present the plan for the IMA process. These meetings should reinforce the charter and present the straw-man vision as such.

Make commitments to business leaders about how the IMA and resulting digital identity infrastructure will positively affect their business to generate support. Such commitments will be contingent on key assumptions being met. Be sure to document these commitments and be accountable to them as the process matures.

With these steps completed, it is time for a series of meetings among those in the enterprise who are the influencers and leaders. The goal of these meetings is to establish a shared vision, translate the high-level objectives into more specific goals, and assign roles to specific members of the organization. These facilitated meetings should build from the “straw-man” vision developed earlier into a group consensus around the outcomes that will result if the IMA process is successful.

Facilitated meetings are an established way of creating shared vision, and I recommend that you employ a trained facilitator. An experienced facilitator will be able to consult with you on specific techniques for achieving the goals of the initiation phase, and can help adjust the meetings and processes accordingly.

IMA Governing Roles

Assigning roles and responsibilities for the IMA effort is an important step and should occur as a result of the meetings that create the vision. Rather than define these roles in terms of positions, we’ll describe them generically with some hints as to how these generic roles map onto some common organizational structures.

The roles that we discuss in this section were influenced by the NASCIO Enterprise Architecture toolkit.[*] The NASCIO toolkit identifies eight primary and seven supporting roles in the creation of a governance model for an enterprise architecture. I’ve adapted those roles into an IMA process. There are two categories of roles: primary and supporting. The model in Figure 14-2 shows only primary roles for clarity. Table 14-1 shows the primary and supporting roles that support the IMA governance process.

|

Primary roles |

Supporting roles |

|

Audience |

Enterprise executive |

|

Champion |

Subject-matter expert (SME) |

|

Overseer |

Technical operations staff |

|

Manager |

Product/project teams |

|

IMA team |

Procurement manager |

|

Communicator |

Special interest groups |

|

Advisor | |

|

Reviewer | |

|

Auditor |

Primary Roles

Primary roles are those that directly perform the work of creating the IMA.

- Audience

All of the stakeholders in the IMA effort take on the role of audience. These stakeholders include the enterprise executive, business executives from other parts of the organization, IT staff, partners, suppliers, and customers. Understanding the audience will provide significant guidance to the IMA effort. The audience will eventually have to live with the results of the IMA even though they are not necessarily participating directly in its creation. Communicating the IMA process, progress, and results to the audience is critical.

- Champion

A champion is the person pushing the project and putting energy and resources into moving it forward. Typically, the champion will be a high-level executive (say, the CIO) who has decided that creating an IMA is an important strategic objective. That doesn’t mean that the champion was the first to see the advantage of an IMA. Indeed, someone else will typically have sold the champion on the merits of digital identity.

- Overseer

Overseer is a role that is typically implemented by a committee or team. The overseer’s role is to provide oversight for the IMA project and ensure that the mandate of the enterprise executive is fulfilled.

- Manager

The manager is the executive responsible for directing the overall IMA effort, and ensuring that the directives and requirements of the overseer are met. The manager works with the champion to select people to fill other important roles. Often the manager and the champion are the same individual. The manager needs to have sufficient standing in the organization to effectively carry out the mandates from the champion and overseer. As such, the manager is typically a senior-level IT employee. The manager has the following responsibilities:

Select people to serve as reviewers and chair the activities of the review function.

Select the communicator and ensure that the communicator has instructions about how, what, and when to communicate. The manager ensures that communication is supporting the overall IMA effort.

Seek out and work with advisors to ensure that the process is following best practices.

- IMA team

The IMA team is the heart of the IMA model. The IMA team does the actual work of creating the architecture and will typically consist of a few knowledgeable IT staffers. The champion and the manager should trust the IMA team. Further, members of the team should have a mature understanding of the business and its goals as well as identity technologies. The IMA team might also include in a support role, subject-matter experts, or members of the service, project or product teams. The IMA team should not be populated solely with the existing information security group, although some members of that group should either be on the team or designated as subject-matter experts.

The IMA team is charged with creating and maintaining the documents that make up the IMA. The key requirement for this function is the ability to understand the process and write clearly.

The IMA team has the following responsibilities:

Create IMA documents in consultation with the manager, reviewer, and advisor, after carefully considering the audience.

Provide the communicator with the information necessary to communicate the plan and process to stakeholders.

Provide IMA deliverable documents to the reviewer.

Update the documents according to input from the reviewer and manager.

This role can take a significant amount of time and may need to be full time in a large organization.

- Communicator

The communicator’s role is to provide information about the process, progress, and results of the IMA to the audience and people in supporting roles who are not involved in the day-to-day effort. We assume that those in primary roles get information about the IMA through their participation, but if that’s not the case, the communications plan should include them as well.

The communicator receives information from the IMA team, the reviewer, and the manager. The communicator and the manager make this information available to the audience and others in accordance with a jointly created communications plan. The communications plan does not need to be elaborate, but should take into account the differing needs of the people in the audience and other roles. For example, the audience includes customers who may need to be told very little about the IMA itself but get detailed information during the implementation phase. The objective of the communications plan should be to ensure that members of the audience understand the IMA in the correct amount of detail. Communications should always be written to build support within the enterprise for the IMA.

- Advisor

An advisor guides the manager, providing clarity and supporting best practices. The advisor could be the champion, other enterprise executives, or someone else who has knowledge about the goals and objectives of the IMA, the political landscape within the enterprise, best practices from other organizations, and so on. There may be a number of people who fill the advisor role, and their advice may be limited to areas of specialization. Often the enterprise will bring in an outside consultant who has past experience in creating an IMA to serve in the advisor role.

- Reviewer

The role of reviewer is crucial to the IMA effort. The reviewer is usually a committee staffed by senior executives from the business organizations in the enterprise as well as the IT organization. The reviewer’s role is to evaluate the IMA documents, recommend changes, and to approve or disapprove them.

The people assigned to these roles will change over time, and so change should be planned for and accepted as part of the process. Indeed, the make-up of the groups playing the reviewer and advisor roles is likely to change as the IMA process matures.

Supporting Roles

Supporting roles help create the IMA, but are not necessarily involved in the day-to-day process.

- Enterprise executive

The enterprise executive provides the strategic reasons for creating an IMA and identifying the high-level objectives of the IMA process. The enterprise executive is typically the CEO or other high-level executive who can help the champion and manager bring other players to the table.

- Subject matter expert

The process of creating an IMA will require the expertise of a number of people both inside and outside the enterprise. The manager and reviewer as well as the service, project, and product teams use subject-matter experts.

- Technical operations staff

The technical operations staff is responsible for day-to-day IT operations. This is the group of people who manage the network, operate the servers, and so on. They are a user of the IMA and provide feedback to the IMA team as part of the IMA lifecycle. Moreover, the technical operations staff can provide valuable feedback to the IMA team about what is feasible and what is not.

- Product and project teams

Product and project teams consist of everyone involved in implementing a project or bringing a new product to market. Typically, project teams are used on inward-facing engineering activities, and product teams are used to build things that will be bought by customers (including services). The product and project teams are users of the IMA and can provide valuable feedback to the IMA team. Product and project teams will be required to comply with the IMA in their designs and engineering, so their participation and buy-in is crucial.

- Procurement manager

The procurement manager is responsible for setting and enforcing procurement policies and procedures. These policies and procedures are not part of the IMA, but they can play an important role in helping enforce the IMA, and the policies and procedures in the IMA must be consistent with those of the procurement manager.

- Special interest groups

The role of special interest groups is something of a catch-all role to include those people and groups who provide advisory input to the IMA process, identifying special needs or requirements.

Resources

One of the first tasks and a critical success factor is to find and allocate resources. There are two primary resources necessary to get started: people and computer systems.

The roles discussed in the previous section will be assigned to people within the organization. Customize the roles to work within your enterprise and create an organization chart for the IMA process that mirrors the roles found in Figure 14-2.

Next, determine the time commitment for each role. In a large organization, the IMA team, manager, and communicator roles will likely be full-time assignments. Smaller organizations might assign the manager as full-time and assign IMA participation as an additional duty for everyone else. Additionally, the number of IMA team members varies with the size of the organization. I recommend a team of three to seven people, depending on the size of the organization and whether they are full-time or not. Teams larger than seven people can be unwieldy to schedule and manage. At least one person on the IMA team will need to provide clerical and reporting support.

An important part of assigning IMA roles is to contract for time with the participant’s supervisor. For full-time roles, this may be a formal HR process. For part-time roles, the contract should be a written acknowledgment by the supervisor of the person’s roles and responsibilities within the IMA activity and the expected time commitment each week. Executive intervention may be necessary in this stage to get commitments for the key people.

Team members must be able to easily share their data and documents. Email can fill this need, but you may find that a more formal tool for this purpose is helpful. I strongly recommend the use of a content management system for sharing results, managing document versions, distributing reports, and communicating progress. The content management system needn’t be expensive. Plone, an open source product, will work fine for many organizations. Also, free or low-cost weblog software can be used to communicate progress and important information.

You’ll see, as we continue through the book, that there are survey and data collection aspects to the IMA process. Survey products are available online and should be sufficient for much of the required survey work, but the data will need to be pulled from the survey and manipulated. In many instances, spreadsheets will suffice, but there may be some sophisticated data reporting requirements that require database and web skills that go beyond the ability of a small team to self-support. IT resources for managing the database and wrapping it in data entry and query forms should be committed to the IMA team as necessary.

What to Outsource

One of the primary arguments of this book is that identity is a central to the business, and business goals and IT activities can only be aligned through a new approach to managing identity. Otherwise, why would someone go to the effort of creating an IMA?

That being the case, building an in-house competency in identity and the processes for managing an IMA is crucial. Only by direct contact with the processes and systems will your organization know enough about how identity is being used in the business to have it make a strategic difference.

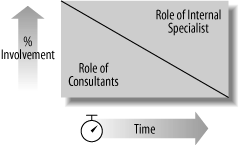

Early in the process, you may need to delegate critical aspects of creating the identity management architecture to outside consultants who can guide the process and have specific skills that in-house personnel do not have. Figure 14-3 illustrates the process of moving from external consultants to internal specialists over time.

The trick to managing this is that if you turn too much over to external consultants early in the process, you may fail to learn the competencies necessary to bring the process entirely in-house. To alleviate this problem, you should avoid putting external consultants in most of the primary roles in the governance process and use them as advisors only. There may be specific tasks that need to be outsourced, such as conducting a particularly specialized set of interviews or a technical survey and analysis. Over time, however, reliance on external consultants will be costly and keep your organization from developing necessary skills. Identity driven businesses should own rather than rent their identity management architecture.

Understanding the Business Context

As part of creating the vision, we discussed the importance of gathering information about the business objectives and goals. That’s a crucial first step in creating a business context within which the IMA can be fashioned.

When I was the CTO for http://iMall.com, I knew exactly what we did: we created specialty hosting solutions, including e-commerce tools, for small and medium-sized businesses. What’s more, I knew exactly who was doing what, because I’d hired most of the 125 employees myself. I had, for all intents and purposes, perfect knowledge of iMall’s business model.

Later, when I was CIO for the State of Utah, I had a much tougher time getting my arms around the business. First, governments are large, even the governments of relatively small states. Second, they do a lot of things. At first it seemed impossible, but there are specific things you can do to understand an organization, even one that’s complex and loosely coupled.

Our model of the business will provide us with two important results: a business function matrix and a set of guiding principles for the IMA effort. Both of these are important to creating an IMA that is sensitive to business objectives.

Business Function Matrix

A business function matrix (BFM) is a matrix that documents the business functions that your organization performs and which organizations within the enterprise perform them. The steps to creating a BFM are fairly straightforward:

Document the structure of your enterprise.

Define the business functions your enterprise performs.

Map the business functions to the major organizations within the enterprise.

Creating the BFM might not take very long in a simple business like iMall. In a complex organization, the process might take considerably longer. The U.S. federal government has a BFM called the Business Reference Model that was assembled over the course of several years.

Organizations’ units are arrayed along one axis of the BFM. The chief decision is how fine-grained you want to be. It’s entirely reasonable to start the process with a high-level, abstract view of the organization and then drill down into more specific information as the IMA process evolves.

The goal of building a business model is to determine what functions various parts of the company are performing. If this were a business book, we’d be concerned with finding out if those activities led to competitive advantage, but that question is clearly beyond our scope. We’re merely trying to find out what happens, not decide whether it’s the right thing or the wrong thing. Your organization may have already performed a competitive advantage exercise, and in that case, the information about who’s doing what will be readily available. In most cases, however that will not be the case, and you’ll have to start from the beginning.

In the end, you should have a list of functions that the various organizations in your enterprise perform. This list should give the function a name, organization that performs it, and contain a brief description. In many cases, the description will be a list of subfunctions. Some of the functions may seem very similar to functions performed elsewhere in the organization. We’ll normalize this list later.

Build the function list by talking to members of the various organizational divisions and asking the following kinds of questions:

What is the business of your organization, team, or group?

What tasks does your organization, team, or group perform?

How do the tasks your organization, team, or group performs contribute to the function of the group or organization you belong to?

As you work your way through the organization, divide each function into subfunctions by decomposing it into smaller steps. “How do you...?” is a good question to ask to get the answers that lead to decomposition.

Remember that our goal is to understand the business and how identity is used in support of business goals. As you perform the functional decomposition, make note of any functions where identity information or activities are being used. This information will be helpful in understanding identity processes that business units use to accomplish their function.

There are a few caveats:

Organizational names are not necessarily good indicators of the functions that the organization performs. For example, “Finance” isn’t a function. If you asked people who work in the finance department what they do, they probably won’t say “finance.” They’ll talk more about the tasks they perform.

Many of the tasks people perform are not functions in the sense we care about either. Examples include sending email, writing memos, and so on. You should steer people toward the reason for sending the email or the business function of the memo or spreadsheet.

Functional decomposition does not necessarily follow the organizational chart, so don’t be caught up in the organization so much that you lose the functional model. Cross-functional product teams who come from many disciplines to build, deploy, and maintain a product are a good example of where organization and function do not match. The product team may not show up in a formal organization chart, but their function is a crucial part of the business.

Keep in mind that you’re not trying to determine workflow or do business process modeling. The scope of those tasks is far greater than what we’re after here and will mire the IMA team down.

Creating the Business Function Matrix

As we said earlier, the BFM is a matrix that maps organizations to the functions they perform. The reason we treat it as a matrix rather than a simple hierarchy, as the results of the last section would suggest, is that more than one group in the enterprise often carries out similar functions. To get a matrix, we must collapse similar functions into more general descriptions and combine definitions where appropriate. I call this process “function normalization.” As you do this, and keep track of which organizations are performing the functions, you’ll find that the matrix creates itself.

One of the things you’ll find is that multiple organizations inside the enterprise perform the same function by description, but they do it in different ways, as indicated by the subfunctions. There are two possibilities:

The subfunctions themselves are the same, once they’ve been normalized.

The subfunctions are substantially different or there are additional steps in some processes.

In the first case, the function can be completely collapsed, after the two subfunction trees have been normalized.

The second case is both frustrating and the reason for doing this exercise. Our job is not to change either business unit so that they use common processes for performing the same functions, but to document what actually happens. This information will be useful when policies are created or systems are being implemented. At that point, the CIO or another appropriate manager may want to initiate discussions about whether these processes can be normalized, but we must accept the fact that often they will not be, and the IMA and related infrastructure will have to accommodate the differences.

Our ultimate goal is to create an identity management architecture and digital identity infrastructure that supports the business. Detailed functional data about how different business units accomplish similar functions in different ways is crucial to creating an IMA that will be used by the business and adds value. Imagine not creating the business model and then finding this out after you’ve spent a lot of money creating an infrastructure that supports one way the business does something but not the others. That’s what causes many IT projects to take longer than planned, cost more than budgeted, or outright fail. Having a good business model helps avoid these issues.

IMA Principles

If you just turned to this section from the Table of Contents, you might be expecting a list of important principles for creating an IMA. Sorry to disappoint you. Rather, this section is about creating your own set of guiding principles that reflect the culture and objectives of your organization.

As I described earlier in this chapter, we created a process for defining how we’d make e-government the standard way of doing business for Utah government. One of the most important things to come out of that process was a set of principles for e-government in Utah (see "Principles for E-government in Utah“).

We created these principles using a facilitated process where over 100 people broke into smaller groups, brainstormed principles, and then chose the ones they thought were most important. We brought all those groups back together, had them present their results, and then the entire group determined a short list of seven principles that were the most important.

I’m confident that we ended up with a set of principles that represented the feelings of the business and IT leaders in Utah state government. Over the coming months, these principles served as a charter of sorts that we could refer to. These principles grounded the discussion in important objectives and kept it on course.

Building a similar list of principles for your IMA process will bring the people whose support you need together and make them feel like a part of the process and the decision making. You’ll be more sure that the decisions made further down the road will gain widespread support if they are based on principles that everyone helped create.

An important part of this process is the up front work to educate the participants in the crucial ideas and let them form educated opinions. We were lucky in Utah that we’d been discussing e-government for several years, so almost everyone had a core set of beliefs and ideas. In addition, Governor Leavitt had been a strong proponent of e-government, and had made his own views evident in cabinet meetings and other venues. These things made our job easier.

One way to jumpstart the process is to get people thinking about where they stand on some key, strategic choices. Burton Group has published a list of IT architecture principle areas that can be used to start a discussion of principles and guide people to an enterprise-wide set of core principles. I’ve adapted these to issues relevent to an IMA. The revised areas are shown in Table 14-2.

|

Management |

Vendor |

User |

Identity |

|

Technology risk acceptance |

Single vendor versus “best of breed” |

Must use versus optional service |

Accountability versus access control |

|

General versus optimal solution |

Second sourcing |

Billing and chargeback |

Partners and federation |

|

Cost center versus competitive advantage |

Proprietary versus openness |

Universal service |

Security versus business enabler |

|

Degree of autonomy |

Vendor risk |

Privacy | |

|

Project justification |

Outsourcing |

Online versus Traditional |

Areas in the Management column raise questions about how management feels. Is your organization risk averse? Does management expect an optimal solution? Is IT (and hence and the identity infrastructure) treated as a cost center or a means of competitive advantage? What degree of autonomy does the IT organization have? Do projects have to be justified in strict ROI terms?

Areas in the Vendor column raise questions about the enterprise’s feelings toward your organization’s relationships with vendors. Do you prefer to work with single vendors or are you comfortable integrating products from multiple vendors? Is it important that you have a second source for mission critical products and services? Do you prefer open solutions? What level of vendor risk is your organization comfortable with? What is your philosophy toward outsourcing?

Areas in the User column raise questions about the enterprise’s feelings toward users. Are users required to use services and infrastructure created by the IMA or is such use optional? Does IT bill for services? Is IT expected to support all users or just some?

Areas in the Identity column raise questions about issues we’ve discussed in the earlier sections of this book. Where can your organization use accountability to augment or replace strict access control? What plans do you have for federating identity information with partners? Does your business see identity in terms of security or as a business enabler? What is the attitude toward privacy? Are you engaged in self-service-style online transactions with your customers?

Don’t try to come up with a principle for each area in Table 14-2. These are just areas to jump-start your discussion. In the end, you should come up with 6 to 12 principles that are the most important to your organization. This list should be communicated widely and used as the basis for the activities that follow.

Conclusion

Creating the governance process, fashioning the business function matrix, and establishing the guiding principles for the IMA are critical steps. They form the backdrop against which we build the IMA. The next chapters will jump right into the specific components of the IMA. The first step is to understand the identity management maturity model and build a process architecture.