Chapter 3. Trust

In the influential book Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, Francis Fukuyama argued that public values, especially trust, shape the direction of national economies. Among other things, Fukuyama shows how trust reduces transactions costs, and ultimately, economic friction. In a smaller way, being able to use a digital identity infrastructure to establish and capitalize on circles of trust within your organization, and between your organization and its partners and customers, may very well shape the direction of its success.

Trust is an important and yet tricky topic. Ultimately, every authorization made using a digital identity infrastructure is dependent on trusting that an identity and its attributes are correct. At the same time, trust is a concept that humans understand implicitly but have difficulty capturing algorithmically. Various mechanisms for establishing trust in identity credentials are available. This chapter introduces the notion of trust and the methods used to achieve it, but details of how those technologies are used to build trust are saved until later chapters.

In a digital identity infrastructure, trust occurs in a variety of places. Here are some examples of trust:

Trust that the identity credentials are held by the correct entity

Trust that the system I’m talking to is the one I want to talk to

Trust that my communication will be unaltered and private

Trust that the access control policy is implemented consistently throughout the enterprise

When we create a policy about digital identity and the actions available to holders of particular identity credentials, we’re setting out a collection of objectives based on the circumstances of the transactions involved, the business requirements, the degree of risk that the business is willing to bear in those circumstances, and the cost the business is willing to pay to reduce the risk to an acceptable level. These objectives drive the level of trust and the amount of evidence we need to collect to attain it.

Circumstances of the transaction may vary greatly. On one end of the spectrum might be electronic transactions over secure lines wholly owned and operated by the company and on machines that are carefully maintained in secure facilities. At the other end are circumstances where such transactions occur over the Internet using machines that are owned by people who may be actively trying to take advantage of the organization.

Business requirements spell out what has to happen. Sometimes they may also spell out how it happens, as any supplier to Wal-Mart can attest. Business requirements spell out who we are dealing with and why. They also should make the end goal of the transaction clear and set forth the penalties for not achieving that goal.

Risk is something that is managed by the business either actively or passively. Some businesses and people are very risk averse. Others are more tolerant of risk, especially in light of the cost of reducing risk. Even so, our assumption is that most businesses want to reduce the risk attendant to electronic transactions, and understanding the appetite your organization has for risk is critical to building an effective digital identity infrastructure.

What Is Trust?

Trust is a firm belief in the veracity, good faith, and honesty of another party, with respect to a transaction that involves some risk. For example, when you give your credit card to the waiter at a restaurant, you are expressing trust that the waiter will use the credit card to process a transaction that will pay for your meal. You expect that that transaction will be the only one processed and that the waiter won’t steal the credit card number for some other purpose. The only time I’ve ever had my credit card number stolen was in a restaurant, and yet I still blithely hand my credit card over to any waiter who comes along. There is clearly risk, but I take it because I’m convinced that the risk is small. Most of us don’t consciously think about the risk of using a credit card to pay for a meal; we evaluate the risk intuitively based on a variety of factors including our previous experience, the way the restaurant looks, and, perhaps most importantly, beliefs about the credit card company indemnifying us beyond a certain point.

There’s no doubt that trust is linked to risk when we consider who we’re willing to trust with what. I may trust a particular person to fix my car, but not to baby-sit my children. Trust is based not just on the entities involved in the transaction, but also on their roles and the particulars of the transaction.

Trust is something I grant to or withhold from others—they cannot hold it for me. I can adjust it or revoke it completely, at any time. This leads to some important trust properties.

Trust is transitive only in very specific circumstances. For example, if Alice trusts Bob’s taste in music and Bob trusted Carol to select songs for the last party, Alice may be willing to trust Carol to pick the songs for her party.

Trust cannot be shared. If Alice trusts Bob and Alice trusts Carol, it doesn’t necessarily follow that Bob trusts Carol.

Trust is not symmetric. Just because you trust me, doesn’t mean that I trust you.

Trustworthiness cannot be self-declared. This is so self-evident that the phrase “trust me” has become a cliché sure to get a laugh.

In the world of digital identity, trust is generally linked to a particular set of identity credentials and the attributes associated with them. I may have several email addresses, for example, and even though they all belong to me, people may see them in different contexts and trust a request contained in an email from my work address, for example, more than they do from my Gmail account.

Trust and Evidence

One day I went to the store to buy a disposable camera for my son to take to an activity. As I stood before the display rack, I pondered which of several choices I should buy. One bore the brand of a reputable company with a strong reputation in the world of photography. The other camera bore the house brand of the store I was at. The house-branded camera was $1 cheaper than the camera with the national brand. I bought the more expensive camera, even though they may have actually been manufactured in the same facility on the same day. Why? Because the brand was evidence that I could trust that the camera would work and the film would be good quality. The $1 extra that this evidence cost me seemed a reasonable trade-off to avoid the risk of missing the shots.

Just as in the physical world, trust in a digital identity is ultimately based on some set of evidence. For example, when you log into your computer, you present an identity in the form of a user ID and evidence that you are the person to whom that ID refers by typing in a password. The password is evidence that the computer should trust that you are who you say you are.

Sometimes the evidence for trust in a computer-based transaction is explicit and automatically collected as in our password example. At other times, the evidence is present but less visible than in physical situations. For example, when I conduct an electronic transaction at http://Amazon.com, their digital certificate presents evidence to my browser that I’m really dealing with http://Amazon.com and not an imposter just trying to steal my credit card number. While this happens automatically, few people pay much attention to the trust marks that the browser presents (such as the little padlock indicating a secure transaction) and fewer still ever ask to see the details that their browser hides from view. The recent increase in phishing scams, where criminals pose as a legitimate online business in order to steal identity information, is evidence of this.

Passwords, digital certificates, biometrics, and the like are all examples of evidence that can be presented to show authenticity for a particular set of digital identity credentials. Chapter 7 discusses the collection, use, and relative merits of the various types of credential evidence used with digital identities. Other systems for recording and measuring trust will be discussed at other locations.

One of the chief impediments to flexible digital identity infrastructures is that current methods of managing policy and trust are inflexible, slow, and costly. New requirements, such as federation of identities across corporate boundaries, exacerbate the problem. There is considerable work taking place on languages for expressing policy. We’ll see an example of such a policy in Chapter 11. The ultimate goal of such policy languages is to create machine-readable policies that are consistent, adaptable, and function in heterogeneous environments. Current state of the art in policy management is still quite a ways from this ideal condition, so we will see in Chapter 18 how to use enterprise governance to create a process that makes up for some of the deficiencies of the technology in the area of policy management.

Trust and Risk

Trust can be difficult to quantify. Do I trust Alice more than Bob? Why? Unfortunately, when evaluating the effectiveness of identity policies, we need to be able to quantify the trustworthiness of a system, method, or technique. Fortunately, we don’t ultimately have to measure our trust in a system or approach; rather, we can try to quantify the risk of a particular business process and balance that risk with the expected rewards or returns. Businesses have been analyzing risk for years.

Analyzed in this way, for each business process, we have to be able to give a measure of the risk that the digital identity infrastructure will fail to perform as required for that particular business process. To answer these questions, we need to have a detailed understanding of the systems and processes that make up the digital identity infrastructure, including detailed assessments of the required interactions with partners and their ability to perform as required. Further, we have to quantify the potential losses and their probabilities.

Often, for processes that have been in place for some time, we can use historical measurements to determine the expected level of risk. This assumes that the processes used to manage the digital identity infrastructure include system and outcome monitoring and tracking.

The level of detail available for these analyses will depend on the maturity of our identity infrastructure, a topic we will return to in Chapter 15.

One way to manage risk is with service level agreements, or SLAs. SLAs are nothing more than contracts that set expectations around what you are promising and what the consequences will be of failing to deliver. A complete discussion of SLAs and risk management is beyond the scope of this book, but should play a part in your digital identity strategy.

Reputation and Trust Communities

I just bought a cell phone cover on eBay from someone in Hong Kong. Normally, I’d consider an international purchase pretty risky. But eBay provides a means for me to gain trust in someone living in Hong Kong. The trust is based on feedback from other eBay users. Each time an eBay seller completes a transaction, the buyer can rate the seller on a number of different points. When I bought my cell phone cover, I was able to review the seller’s history on eBay and determine that other buyers were happy with their interactions with this seller. In the same way, sellers can see a buyer’s reputation to determine if the buyer is trustworthy and therefore likely to complete the transaction. eBay’s feedback system creates a social network wherein reputation can flourish. This social network aggregates the reputations of eBay buyers and sellers into a community of trust.

In that way, eBay is like a village where trustworthiness is based on one’s reputation. First-time sellers, like strangers in the village, have no reputation and are thus viewed with suspicion. Over time, this changes for better or worse depending on the actions of the person. On eBay, identities, rather than people, gain a reputation over time, and that reputation can be used to judge a particular buyer or seller.

eBay, of course, is not the only example of a system where this kind of trust community has developed. MSN Messenger, for example, serves as the infrastructure that supports a community for securities traders. Over the course of time, individual traders, identified by the MSN Messenger ID, build a reputation based on what they say and do.

Similarly, over time, people build up trust in the email addresses of people with whom they’ve interacted. Unfortunately, as we’ve seen, the lack of credible authentication for those identities makes them subject to exploitation by email worms and viruses.

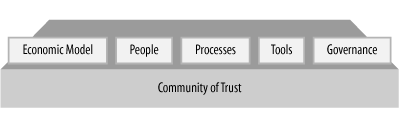

Given that communities of trust are so important to trustworthy interactions, we might ask how they are constructed. As illustrated in Figure 3-1, a community of trust has five components:

Governance, which describes the operating rules, roles and responsibilities, and legal validity of the policy

People or other entities involved in the trust relationships

Processes for performing operations and transactions

Technology tools, including software and hardware

A viable economic model

Let’s look at how each component plays a part on eBay. First of all, eBay has established a set of rules and policies about how sellers and buyers should act and what they can and can’t find out about each other. Buyers and sellers are represented by digital identities that are protected by an authentication system. There is a process

for establishing feedback, and this process is embodied in the feedback tools that are part of the eBay site. Finally, the economics of this trust community are simple: the sellers pay for any costs needed to maintain the system out of their commissions. Moreover, the buyers and sellers carry the risk of the transaction, not eBay, which cuts the cost dramatically.

In contrast, Public Key Infrastructures, which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 6, is an example of a technology that has failed to develop a widespread community of trust, at least among individual users. Its true that many have struggled with the technology and tools—current tools are too complex—but more importantly, the economics of widely issuing digital certificates has been a hurdle. A large part of the cost comes from that fact that certificate authorities are legally certifying that the holders of the certificates are who they say they are. This means that they are liable and carry at least a portion of the risk. Certificate authorities have to charge money to cover this potential liability.

Conclusion

We can create digital identities all day long, but they are worthless without authority. As we’ve seen, authority is established on the basis of trust, but trust is hard to measure. In building digital identity infrastructures, remember that you’re attempting to establish a community of trust, even if trust is never mentioned.