While talking to Dan Jeup one day, he mentioned “Iazy lines.” He was referring to lines that didn’t describe anything like shape, texture, softness, or hardness. It’s like what you get when you trace something, an overall sameness of line. Granted, when you are using a mechanical pencil as we are on “Mermaid,” that in itself cuts down on possible variations of line. However, the problem of lazy lines goes deeper than just the surface patina, it has to do with the lack of basic drawing.

For instance, the same pencil makes a line for a bird’s beak as for its feathers. If the artist does not feel the difference and try to inject that feeling into the drawing, then both lines will look alike — these are lazy lines. And incidentally, they look like a tracing.

Many factors go into the drawing of any part of a bird, and the mind must be focused on each thing separately yet simultaneously. A Zen saying may help to clarify what I am trying to say: “When I am walking, I am walking; when I am eating, I am eating.” It simply means that when you are walking, enjoy the fact, instead of planning what you are going to do about the rent payment or what you should have said during yesterday’s discussion on politics. Now is the only moment you have — live in it. Someone said “Thank God we only live one moment at a time — we couldn’t handle any more than that.”

Back to walking. When I am walking, I am (just) walking. I feel the cool breeze or the soothing warmth of the sun, I hear whatever sounds pass into my consciousness. I feel my heels strike the ground as they make contact. I enjoy the sway of my body as it negotiates for balance and forward motion. I watch the scenery go by and am aware of the third dimensional quality unfolding around me. These factors are all happening simultaneously yet can be enjoyed separately. The same goes for every activity of your daily living. It is possible to go through life (or sometimes just big chunks of it) in a sort of dream state wherein you don’t really experience the things you do. And so it is possible to make a drawing (many drawings) without being wholly conscious of what you are drawing.

To apply that philosophy to drawing you simply have to realize, when you are drawing a beak, you are drawing a beak; when you are drawing a feathered head, you are drawing a feathered head. And that goes for any of the hundreds, or will it be thousands, of separate parts you will be called upon to draw. This may seem contrary to my usual preaching about not drawing details in the gesture class. It is a matter of sequence — first the rough gesture drawing, then the detail. The line used to lay in the pose or action (acting) can be all one kind of line, as long as it is flowing, expressive, flexible, searching, and basic. The line to “finalize” the drawing must describe the shape, texture, and malleability of each part. So when drawing a bird’s beak, you should aspire to make the drawing say “beak.” When you get to the feathered part of the bird, you shift gears or press the “When I am drawing feathers, I am drawing feathers” button.

I fully realize the pressure levied on you by the production schedules, but it really takes but a split second to alter your thinking as you move from one texture or shape to another. Just being aware of what you are drawing will help to elevate your line from “lazy” to “expressive.”

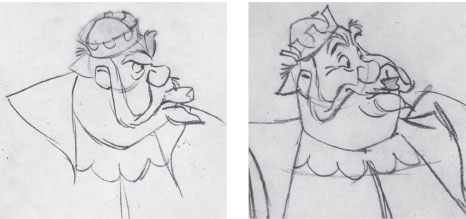

The bird beak and feather thing is pretty obvious, so for a demonstration I’ll use a character with a metal crown, some areas of hard and soft flesh, and some hair and cloth:

Let’s start with the crown. In reality it is a very inflexible, rigid, and lifeless object. It must be drawn so it looks like metal, though in animation liberties may be taken with its shape. For instance, to enhance a raised eyebrow or a frown, it can be contorted to accommodate the expression. Its shape may be altered to help other actions too; for instance, here the crown of the crown still fits snugly onto his head but the brim leans forward helping the direction of the look. Also notice that since the head is tilted to our left it sets up a squash on that side and a stretch on the other side, and the contorted crown shape contributes to that very important animation gimmick, squash and stretch. Even so, it remains rigid and must be drawn so as the surrounding hair and flesh work against it with their softness and of course, more extreme flexibility; that is soft and flexible non-lazy lines.

Take the hair. Its basic shape is this.

![]()

In movement it never loses that basic appearance but may squash and stretch and overlap to enhance the head moves.

![]()

So, as you “Zen” your way through the drawing, you come to the face. You say, now I am drawing the bridge of the nose,

![]()

now the top of the nose,

![]()

now the front of the nose,

![]()

now the part under the nostril,

![]()

now the back of the nostril

![]()

And now the top of the nostril.

![]()

Those are all separate parts of the face and must be kept in mind as you are drawing them. If you think of all that as just one big shape it will end up as a lazy-line drawing.

![]()

When drawing a cheek it is not just a line you are putting down, it is a shape made of very flexible flesh over a fairly rigid bone structure. So when the chin is pulled down, the cheeks stretch and usually there is a bag under the eye. At this stage it is a bag you are drawing. When the mouth smiles, it pushes all that flesh up and pretty soon you are no longer drawing a bag under the eye — you are drawing the top of the cheek. The highest part of the cheek is found at a point where the mouth would have touched it had the mouth line continued up that far. So then you say, I am drawing the bottom of the cheek as it hangs over the corner of the mouth, which in this case is covered by the mustache, not a lazy-line mustache, but one that is drawn in a way that suggests a smiling mouth. Now I am drawing the flesh that is slightly more rigid, which is trying to stay where it belongs. It is connected to the other line but is a different thing and requires thought to depict it as a separate thing. Now I am drawing the front of the cheek as it bulges forward over the backside of the nostril wing. Suddenly it is not the back of the nose you are drawing — it is the cheek.

Now I am drawing the top of the cheek. The part nearest the nose and the ear try to stay put, so you get a bulge of loose flesh between two ends that trail off to where they are attached more firmly.

Lazy lines would not spell out all that action. They would simply be there, not describing what is actually happening in a realistic manner.

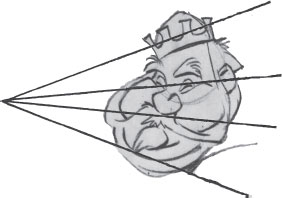

And as if all that wasn’t enough, to keep you thoroughly occupied, you have to fit all those parts into the perspective of the layout. So you have to constantly remind yourself of where the vanishing point is and see that each of parts are loyal to the layout.

If you are a “lazy line” person all this will seem like an unbearable burden, but if you love to draw and can incorporate the “When I am drawing this, I am drawing this” bit, your job of drawing will become very meaningful and sparks of enthusiasm will put a twinkle in your eyes and a sparkle in your drawings.