84 Driving Force Behind the Action

In the evening drawing sessions I try to direct your thoughts to the gesture rather than to the physical presence of the models and their sartorial trappings. It seems the less the model wears, the more the thinking is directed to anatomy, while the more the model wears, the more the thinking goes into drawing the costume. It’s a deadlock that you can only break by shifting mental gears (there’s that phrase again) from the “secondary” (details) to the “primary” (motive or driving force behind the pose). Remember, the drawing you are doing in class should be thought of as a refining process for your animation drawing skills.

I found something in Eric Larson’s lecture notes on entertainment that may be of help to you. Please bare with the length of the quote, it is put so well I couldn’t edit it without losing some of the meaning. As you read it keep your mind on gesture drawing.

…As we begin the ‘ ruffing out’ of our scene, we become concerned with the believability of the character and the action we’ve planned and we give some thought to the observation of Constantin Stanislavsky. ‘In every physical action,’ he wrote, ‘there is always something psychological and vice versa. There is no inner experience without external physical expression.’ In other words, what is our character thinking to make it act, behave, and move as it does? As the animator, we have to feel within ourselves every move and mood we want our drawings to exhibit. They are the image of our thoughts.

In striving for entertainment, our imagination must have neither limits nor bounds. It has always been a basic need in creative efforts. ‘Imagination,’ wrote Stanislavsky, ‘must be cultivated and developed; it must be alert, rich, and active. An actor (animator) must learn to think on any theme. He must observe people (and animals) and their behavior — try to understand their mentality.’

To one degree or another, people in our audience are aware of human and animal behavior. They may have seen, experienced, or read about it.

Because they have, their knowledge, though limited, acts as a common denominator, and as we add to and enlarge upon said traits and behavior and bring them to the screen, caricatured and alive, there blossoms a responsive relationship of the audience to the screen character — and that spells ‘entertainment.’

How well we search out every little peculiarity and mannerism of our character and how well and with what ‘life’ we move and draw it, will determine the sincerity of it and its entertainment value, we want the audience to view our character on the screen and say: ‘I know that guy!’ (or in the case of gesture drawing: ‘I know what that person is doing, what he or she is thinking.’) Leonardo da Vinci wrote: ‘ Build a figure in such a way that its pose tells what is in the soul of it. A gesture is a movement not of a body but of a soul.’ Walt (Disney) reminded us of this when he spoke of the driving force behind the action: ‘In other words, in most instances, the driving force behind the action is the mood, the personality, the attitude of the character — or all three.’

Let’s think of ourselves as pantomimists because animation is really a pantomime art. A good pantomimist, having a thorough knowledge of human behavior, will, in a very simple action, give a positive and entertaining performance. There will be exaggeration in his anticipations, attitudes, expressions, and movements to make it all very visual.

The pantomimist working within human physical limitations, will do his best to caricature his action and emotions, keep the action in good silhouette, do one thing at a time and so present his act in a positive and simple manner for maximum visual strength. But we, as animators, interpreting life in linear drawings, have the opportunity to be much stronger in our caricature of mood and movement, always keeping in mind, as the pantomimist the value and power of simplicity.

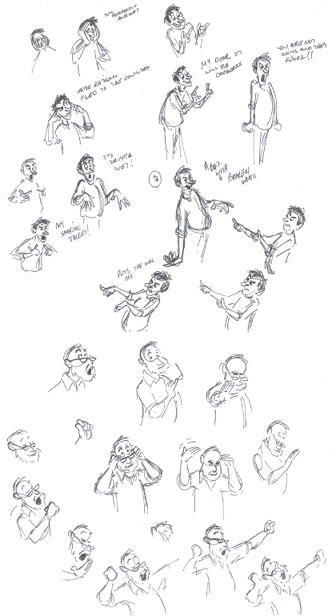

Below are some excellent examples of what Walt must have meant by, “…the driving force behind the action is the mood, the personality, the attitude of the character….” They are sketches Mark Henn did while at a recording session for the Great Mouse Detective.

Actually we create nothing of ourselves, we merely use the creative force that activates us. And when we draw we are not using the left brain to record facts — we have shifted gears and are now using the right brain to create a little one-picture story with, of course, the facts that the left brain collected and named and itemized in former study periods. This is not a study period; this is a show-and-tell period (any time we are not studying).

We are not the car parts in the design room or where they mold the parts or on the assembly line. We are the car full of gas, traveling along the Pacific Coast Highway, heading for a nice seafood restaurant in Carmel.

Do you feel that you are too limited in knowledge? Robert Henri, that great teacher of art, said that anyone could paint a masterpiece with what limited knowledge they have. It would be a matter of using that limited knowledge in the right (creative) way. Have you ever seen the “knowledge” or drawing ability of that great painter Albert Ryder? Probably not. But when you look at his nebulous paintings of ships at sea or skeletons riding around with nothing on, you sense the drama and have a feeling a story is being told. If its facts you want, pick up a Sears’ mail-order catalog.

I’m not advocating abandoning the study of the figure. Anatomy is a vital tool in drawing, but do not mesmerize yourself into thinking that knowing the figure is going to make an artist of you.

What is going to make an artist out of you is a combination of a few basic facts about the body, a few basic principles of drawing and an extensive, obsessive desire and urge to express your feelings and impressions.

The violinist Yehudi Menuhin started out at the “top” of his profession. He played in concerts at a very young age and in his late teens was world famous. Suddenly (if late teens is sudden) he realized he’d never taken a lesson — he didn’t know how he was playing the violin (the right brain had not been discovered then).

He worried that if that inspired way of playing ever left him he would not be able to play. So he took lessons and learned music (finally getting the left brain into the art).

It didn’t alter his playing ability but it bought him some insurance.

I’m suggesting that somehow he had early on tapped the creative force and bypassed the ponderous study period, like all geniuses seem to do. I have a Mozart piano piece that he wrote when he was around nine years old. I’ve been working on it for years and still can’t play it. Who does he think he is anyway?

I’ve been studying piano for umpteen years and I still don’t know the key signatures. The left side of the brain is absolutely numb. But when I sit down to play the piano sometimes that creative force takes my hands and extracts a hint of emotional sound out of the music. That’s all I really care about. My sketching is the same way. I don’t know a scapula from a sternum but when I venture out into the world with my sketchbook, I am able to distill my impressions into a one-frame story that totally tells my version of what I saw. When my wife Dee and I go on a vacation, she takes the photos and I sketch. She records the facts — I record the truth.

Shift gears! With the few facts you have go for the truth!