81 Tennis, Angles, and Essences

One thing is for sure, to acquire a certain degree of skill or expertise in any undertaking the basics must be studied and conquered. Drawing, animation specifically, is no exception. Once the basic rules and principles are thoroughly ingrained, they can be applied to all the variations of problems that will confront us — and confront us they will.

The game of tennis has a few basics that when once learned are applicable throughout the game. For instance, once you learn what a “forehand drive” is, you soon realize that that shot doesn’t cover just one tiny area of the total. It covers any ball that comes to your right side (if you’re right handed), anywhere from the ankles up to around head height, providing it bounces once on the court before it gets to you. Beginners who are not yet aware of this as a category of shot will be confused, because it comes at them anywhere from the center of the body to way beyond their reach, and as I mentioned, from the ankle to head height. It’s like being “splayed” by a machine gun of tennis balls. You may find a waist shot at arms length fairly easy to handle, but these things are coming at you like swallows entering their nesting place at sundown.

So you study and learn this one stroke, the forehand drive, which requires, more or less, one particular “principle” of stroking. Just knowing that much makes it easier to adjust to the variety of heights and distances and speeds of balls, so you can adapt your body movements, weight distribution, speed of racket, footwork, etc. Anything over the head merges into the area of an “overhead” shot, which requires a technique of its own. Anything that bounces just before you hit it is a “half volley” shot that has its own rules for handling. The forehand drive is just one of many shots a tennis player should have in his arsenal of shots.

I didn’t mean to bore you, but I thought it might illustrate the fact that knowing a particular problem so you can deal with it on its own terms makes sense. It takes all the mystery and confusion out of it. It allows one to isolate a problem and to work on it alone and by repetitive practice, “groove” it to perfection, and to learn it so well that it becomes second nature. Not that you won’t have to think anymore, but that thinking about it will not cause you to lose your main trend of thought, which of course in animation is acting out your characters’ parts on paper.

The use of those rules of perspective I mention so often may be likened to shots is tennis. To avoid belaboring those rules too much, let’s use angles as an illustration of a “stroke” in our arsenal of shots. Every gesture or pose is loaded with angles, but if they are not recognized as potential point winners, we might just gloss over them. I don’t want you to gloss over that word gloss either. It means superficial quality or show — a deceptive outward appearance; to make an error, etc., seem right or trivial. If we gloss over enough of those kinds of drawing “strokes,” we will end up with a “love game,” in other words a nothing drawing.

Back to angles. If you want to make a strong statement, and even subtle poses and actions can be strong statements, pay special attention to angles; especially if you work roughly, then “clean” your drawings up later. (after the initial spurt of enthusiasm and clarity of vision has left you). Then later a cleanup person will work on it, who never had your enthusiasm or clarity of vision, and perhaps soften the angles just a little more. Your accolades will be soft too, for it is the strong statements that get the oohs and ahs. Don’t confuse angles with angularity. Some of the most graceful people are put together with 45-degree angles. Watch them — they seem to have studied how to play one angle off another to create those tantalizing poses. Sometimes the changes of angles of cheek against neck, or hand against cheek are so subtle they are felt rather than seen. If you are just looking they are seductive, but if you are drawing, they suddenly become almost invisible — difficult to see and capture. That’s why sometimes you have to draw not what you see but what you know is there or what you feel is there.

Last week while making suggestions on some of the class drawings I concentrated on angles. Sometimes the angles were just barely discernible on the model and needed special attention to find. Once found they needed accenting to make sure they would still be subtle, but at the same time a strong statement.

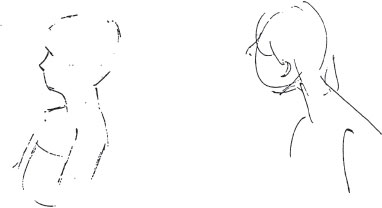

This was beginning to be a nice drawing, but was also becoming a straight up and down thing. The pose had some subtle angles that I tried to point out.

If I had not interrupted this sketch it might have turned out to be a very sensitive drawing. But the whole gesture was overlooked. Note the acute angles the gesture needed to get its story told — not just the neck angle but the face angle against the neck, the front neck angle against the back, the neck angle against the shoulders. One should never work one angle by itself. Angles must work against other angles to contribute to the overall maximum statement.

This is not a bad drawing, but I felt it missed a very subtle thing going on in the pose, which a few lines and some definite angles captured.

In this pose I didn’t feel the head was leaning on the hand. Through the use of a “surface line” I lowered the face so it angled into the fingers to show the weight of the head. The hand and arm became a tangent so I bent the wrist to introduce an angle (which helped to show the weight of the head also). The trapezius muscles and shoulders became too symmetrical so I offset them with more interesting angles and introduced a neck with its third dimensional “overlap.”