Again, in our model sketching sessions we naturally employ our efforts to drawing the model, but our attention is directed not so much to copying or getting a photographic likeness but rather to studying and capturing the essence of the poses. Our goal is to be able to apply the principles we learn to our animation drawings — whether we are animating, cleaning up, or inbetweening. Some of the main things we should be concentrating on are the basic principles of squash and stretch, balance and weight distribution, and how these things work for us in animation. Copying the model without this awareness would be like copying a novel to learn how to write novels.

In every move a figure (human or cartoon) makes its adjustments in the various parts of groups of parts to pull off the move. Usually a preparation of anticipation precedes the move and more than likely involves a squash, plus the distribution of weight to intensify the thrust of the move. The move or action itself usually is a stretch. But even in an extreme squash drawing, some parts have to stretch to get into that position.

The principles involved are simple and obvious and are applicable to any action. If the body leans forward to grasp some object with its outstretched hand — there must be stretch, and there must be an adjustment in weight distribution such as counterbalancing with the opposite arm, and placing one foot closer to the object than the other to keep the body balanced. There are other things that will contribute to the reach also. Eye contact with the object funnels the attention to the reason for the action; keeping the path between the hand and the object and the eyes and the object clear of any obstruction, opening the hand in anticipation for the grasp. Timing, which we can’t depict in a sketch, is also important. It will be different for delicately picking up the object as opposed to seizing it in a broad sweep of the arm, plus of course the continual redistribution of weight, and the choice of which part of the move will be reserved for the extreme, extreme.

So our real goal in studying a model is to draw not bones and muscle and insignificant details but rather squash and stretch and weight distribution, plus — just to keep life interesting — composition, shape and form, perspective, line and silhouette, tension, plans, and negative and positive shapes, to mention a few.

The point is if we go at drawing from the standpoint of anatomy or model we are less likely to achieve the expression we are after, whereas if we work out some symbols for squash and stretch and apply them to anatomy, we can achieve our sought after gesture — then bring it onto model, along with other refinements later. Milt Kahl and Ollie Johnston could animate with all those refinements, but let’s face it we are not that far along (as yet). If we are talking cleanup or inbetween we still have to start with the gesture before getting involved in the details of model and line and color separations; things that are important but only after the storytelling gestures have been taken care of.

Simply put, a straight line is the symbol for a stretch, and a bent or folded line is the symbol for a squash. So whether the action is a broad stretch of the arm and body, or a subtle stretch on a face caused by a smile or an open mouth — the symbols are applied to the anatomy to put these ideas over.

Time should be set aside for the practice of sketching with these symbols. I do not mean merely drawing with straight and curved lines per se, but rather to modify the anatomy to encompass these principles in drawings that are flexible enough to mold into the desired gestural needs. This flexibility should be encouraged and nurtured. To sketch in a rigid fashion discourages adjustments and improvements. “Hey, I just drew a great arm — it may be in the wrong place, but it’s such a great arm — I’ll just alter the rest of the figure to fit it.”

The goal is to find the essence of the gesture and make all the parts of the body contribute to and enhance that gesture.

There once was an artist who sketched

So a career in the arts he thus fetched

He studied in class

But oh my, and alas

When his drawings weren’t good he was wretched

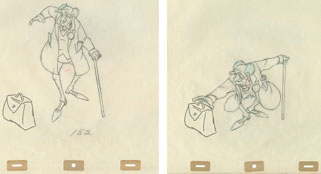

A Milt Kahl example of anticipation (preparation) and stretch.

Inanimate characters also stretch and squash.

An example of the observations that might be made by flipping and studying just these two drawings. By shifting your eyes from one drawing to the other you can see these things happening. Watch the negative shapes change also.