On April 4 and 5 we had Ken Martin, mime, posing for us in the evening class. I watched him closely as he changed from one pose to another. Coming out of a pose was like deflating a balloon that had been blown up with some magical life giving gas. Then there was a pause as the human mime shifted his human body into what the human mind had contrived. You could see the mental wheels turning; you could sense a process of metamorphose like when a butterfly emerges from the pupa stage, or when mixing red and blue paint together and they become purple. Suddenly out of nowhere there was this pose. It was like being transported into a small portion of some fanciful world — just the mime’s portion of it — isolated there on the model’s stand. And he would hold that intense, fanciful preoccupation for ten or fifteen minutes. His concentration on that pose seemed constantly fed by some power source within him, so that, even as electricity flows continually into a light bulb to sustain the light, the mime’s intention flowed into the pose, keeping it alive. And each time you looked at it, it was as if seeing it for the first time.

You, the artist, are in a sense, a mime too. They do it with their body — you do it with pen or pencil. Read that paragraph again substituting yourself in place of Ken. You are performing for the viewer. You are the one who has to bring that fanciful world to life, to a kind of reality. You are the one who has to shift into that fanciful world. You are the one who has to sustain that intensity of interest until the job is completed. You are the one who has to summon up constant renewal from within, as with electricity which sustains the lamp’s light. It is you who has to get a good, exciting, imaginative gesture down on paper. And no matter how difficult the job (or how tired you happen to be), it has to look as fresh as when you first saw it or conceived it: just as exciting, shocking, or awesome; just as new or deep-felt.

Ken will be with us this week again. In these sessions he will tell us about his methods, his inner motivation, and how he translates that into its physical counterpart. It should be very exciting.

We were fortunate to have the San Francisco Mime Troupe give a demonstration and workshop. We learned that their approach to theater is to satirize people and ideas, provide music and entertainment, and to give a “shot of hope.” They shun subtle revelation of character, intense psychological truth, and deep probing of personal relationships. They practice two forms of theater: commedia, designed to make you laugh; and melodrama, designed to make you cry.

To bypass having to develop their characters as the play progresses, they have developed (or distilled) eight types of characters for commedia and eight types for melodrama. As soon as one of these types walks on stage, their character is instantly recognizable, so the audience is not waiting to find out who they are, but what they will do, and what will be done to them.” The actors merely learn the physical attributes of each stereotype, and play that to the hilt. Some of the animation characters are, for instance, Donald, Goofy, and Bugs Bunny. The way they enter a scene tells you that something of a stereotypic nature will inevitably happen. Most of our feature characters have some of the attributes of the 16 mime stereotypes but usually their character is developed as the story progresses.

Animators can benefit from a general knowledge of the stereotyped characters, but their acting requirements extend far beyond merely pigeonholed characterizations. Cartoon features are more complicated than melodramas, so they require more versatility than the mime has. There is need for a wider scope of acting ability. The animator must be thoroughly grounded in drawing and acting techniques. Drawing alone is broken down into a knowledge of anatomy, perspective, foreshortening, squash and stretch, silhouette, overlap and follow through, caricature, and much more. The animator’s range of acting abilities must cover human, animal, birds, fish, mechanical props, and special effects, such as water, smoke, etc.

There is a similarity to both the mime’s and the animator’s techniques. Neither should rely on their knowledge of the stereotyped characters or stereotyped action. True, there is a sort of universal body language, but its application should be always fresh, imaginative, and creative.

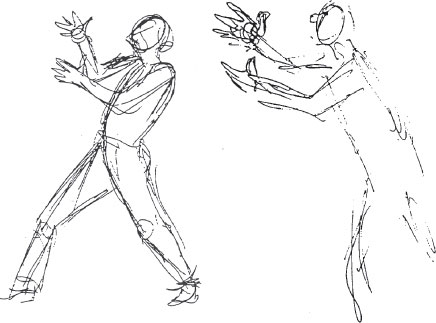

I saved some drawings from the class that suggest possible solutions to some of the problems that plague us. In the first one, a view of a pose which seems to hide what is really happening, I advocated “cheating!” I merely turned the subject enough to clarify his stance. There is nothing meritorious about reproducing a straight-on pose, unless you have accepted it as a challenge, but you do owe the viewer a clear picture of what is happening to your subject (your actor). Remember, a drawing that does not tell a story can never be good, and one that does tell a story can never be wholly bad.

In the second drawing it was the same problem — a straight-on view. Just because you get stuck with a bad view of the model doesn’t mean you can’t re-stage it slightly. As a matter of fact, sometimes it best that you do.

In the next drawing I tried to create a deeper interest in whatever the model was pleading to. If it was some kind of supplication, perhaps it could be a little more emphatic, passionate, or deeply felt. Everything in the drawing should point to the object of his plight.

This was a similar pose. When interested in something, you have a tendency to move in for a closer look. Extending the right arm helped to project the look. Opening a passage by separating the arms and staging the hands so they form a kind of tunnel or channel that point toward the object of his pleading, frees that area for the look and attention to travel unimpeded. In the student’s drawing — the elbows touching, the thumbs pointing back, the whole body leaning backward — all tend to focus the attention on the model’s apparent dilemma, perhaps fear, anxiety, or cowardice.

In the next pose, angles and spaces are important in focusing interest on whatever he is looking at. I opened up more space around the left palm to more freely receive the look. I angled the fingers of the right hand to help project the look down to the palm. In the student’s drawing the right hand angles upward toward the face, directing attention to that area, as if making a sounding board for his voice. I made use of angles to propel the interest to the palm. The angles of the student’s face and hands sends the attention in an outward direction.

![]()

It also encloses an area between the neck and the arm, which traps you into a circular motion. You are soon exhausted trying to find a way out. The principle behind the angles is that two lines like this

![]()

are static. By angling one of them, a motion is set up.

![]()

Three or more such lines accelerates the movement.

![]()

Anyway, here is the drawing and suggestion.

Later I made another sketch angling the right hand even farther.

Then I decided to get the right hand out of the way altogether, clearing a direct channel from the eye to the palm of the left hand. Compare it with the original.

Now everything on the drawing converges on that point. Notice how the angles of the upper arms help

![]()

the lower arms, too.

![]()

Even the angle of the hands help.

![]()