You tell a joke, the listener explodes in laughter, and you enjoy that fleeting moment when their enjoyment is at its peak, not only for the fact that you’ve given some pleasure, but you also enjoy that extreme gesture.

You’re watching your favorite sport on TV, or in person. A player seems to “hang in air” or snatch a ball that looks out of reach. It has taken a superhuman effort and you wish you could have a still photo of that extreme or perhaps be able to sketch it. If you were sketching, you would attempt to capture that “extreme” and of course would have to rely on a memorized “first impression” for the extreme only lasts for a split second.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, photojournalist and documentary photographer, was a master at capturing “the decisive moment.” You’ve probably seen a collection of his photographs in a book by that title. Actually Cartier-Bresson started out as an artist. In the early 1930s he owned a brownie box camera and the results he got from the camera led him to switch to photography. “The camera was a quick way of drawing intuitively.” He said the camera was his way of understanding what he sees: “The simultaneous recognition in a fraction of a second of the significance of an event, as well as the precise organization of forms that give that event its proper expression.”

Well, does that not have a familiar ring to it? In your work as artists you have to “recognize in a fraction of a second the significance of an event,” also “the precise organization of forms that give that event its proper expression.” More than that, in animation you not only have to capture that “significance of the event,” but you have to keep the drawings alive that are in-between those extremes. This is done through timing, anticipation, follow through, squash and stretch, and all the other tools of animation.

No wonder Cartier-Bresson switched to photography. All he had to do was push the little lever at the proper time — the “decisive moment.”

In the gesture class we are attempting to discover what it is that makes up that decisive moment. If it isn’t there in the model, we have to create it. The photographer has to rely on his subject to come up with a photogenic gesture. You as an artist have to rely on your own acumen. Sometimes when drawing from the model, and always when creating a scene of animation, you are required to draw on your ability to act or on your ability to mimic a gesture or an action, and certainly, always, your ability to caricature; that is, “organize the forms that give that event its proper expression.”

I’m not putting down photography or Cartier-Bresson. He was a great photographer. I use him as an avenue to reveal some truths about yourselves as artists. For instance, here is a paragraph from Current Biography, 1976. In reprinting it I am not suggesting you all become Balzacs or Poussins, but in your way to “have an appetite for experience and a sense of form in rendering it.”

Cartier-Bresson’s ability to grasp and capture the essential is perhaps partly due to his early training in painting and composition and possibly also to his interest in Zen, but it is as much the result of a rare personal gift for seeking out and relishing life in all its manifold forms. It was in recognition of the multiple aspects of his art that Hilton Kramer, reviewing the 1968 Museum of Modern Art retrospective in the New York Times (July 7, 1968), commented that he is at once the Balzac and the Poussin of the modern camera, displaying both an extraordinary appetite for experience and a sublime sense of form in rendering it.

Last week we sketched Allen Chang, the martial arts model. As he went through some warm-up exercises, we discovered (or rediscovered) that when a subject is moving it is hard to retain in our mind any one position that we have chosen to sketch. When we do pick a pose, we have to lock it into our short-term memory just long enough to get it down on paper. It’s like taking a mental photograph of the pose. If we keep staring at the subject as it moves — all those images start to blend together and we end up with a muddled montage in our minds. It would be better if we could isolate the chosen pose by momentarily looking at it intensely and then close our eyes or look away so that it doesn’t become adulterated by subsequent movements.

That is just one of the many reasons why quick sketching is so important for us to keep up. It sharpens our hand-eye reflexes, which is a valuable thing for an artist/actor/animator. (A new word should be concocted that would encompass all three of those — one for you who are not yet animators, but are included because you are studying all three of those subjects. My wife Dee came up with “artactanim” but we decided that sounded too much like a dinosaur.)

A camera could record all of those subtle nuances of Allen Chang’s warm-up exercises, but that isn’t our business. We want to be able to draw them — and fast. The best suggestion I could come up with was to sketch in the body first. This gives you a center (a home base) on which to connect all extremities. It establishes in a split second where to connect the head, arms, and legs, which, if considered separately and independently, would lead to (especially when in a hurry) panic and confusion. Also, when trying to record something in a hurry, we must stop trying to draw and start sketching. Most of you relied on your normal way of drawing sped up. It looked like one of those Keystone Cop movies where they cut out every other frame. The technique of keeping your pen or pencil on the paper most of the time as you sketch will be less taxing. Who cares if you end up with a few straggling lines wandering here and there? Your sketch will get done faster, with less effort, and it will be more organic; that is, it will be more like the living thing that you are sketching. And it will suggest movement, which is what you’re after anyway.

So in your “mind photograph,” you have already “named” the pose; that is, you have decided what is happening, spotted the over-all shape, the abstract, and in doing this you have picked the points which constitute and define the gesture. Those points will be the elbows and how they work with or against each other, likewise the shoulders, arms, hands, the knees and the feet. You connect those to the body and voila, a gesture drawing comes to life. Sound easy? Well, it is but you have to practice, practice, practice. So keep those sketchbooks within easy reach so you don’t ever have to confess that you photograph more than you sketch.

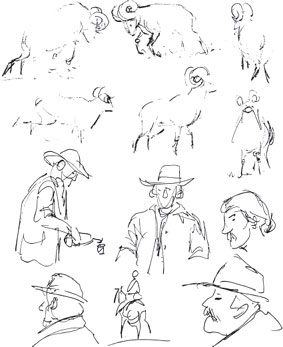

I had some minor surgery recently that forced me to get some physical rest. So I forced myself to watch television at least a couple of hours a day. I chose some shows that lent themselves to sketching. When you do this you realize how heartless the directors and film-cutters are, for you no sooner decide to sketch a scene and what you were honing in on, suddenly is on the cutting room floor. Here are a few examples (mind you, I’m not trying to impress you with my quick-sketches, I’m only trying to encourage you to form the habit of sketching — constantly).