We had mime, Ken Martin, as our model for a second time. In this session he lectured and posed at the same time, illustrating his talk with appropriate gestures. I taped his voice, but the buzzing of the overhead lights interfered badly. I will try to get it transcribed and made available through the research library. I transcribed a bit of it and have woven it into a handout.

Pantomime, the art of silence. Possibly it was the first language. Before the word was the gesture; before the gesture was the need. Everything starts with a need. All art begins with feeling. This need or urge or feeling as it evolves in the body becomes a gesture. Gestures define ideas. Ideas generate energy. This energy travels through the body and emerges from the body in a particular way depending on the idea, and the way you choose to express it much like music. The musician uses notes, tones. His ideas form themselves in his mind as tunes and melodies, which he puts down on paper to be eventually played by himself or by an orchestra. Other people’s needs emerge from their bodies in terms of painting or sculpture. The painter uses line, form, color, space … his ideas come out that way. The dancer uses his body in space. His feelings, needs, and urges come out in terms of rhythmic, physical movement. The writer expresses himself with words, putting his ideas into words — written so other people can read them. The mime uses only his body in space.

Ken said the mime’s job is to create a kind of outline, minus props and sets, and the audience fills in with their imagination. In contrast, the animator uses props, plus third dimensional backgrounds, plus dialog to convince the audience, leaving nothing to chance. But the artist should employ the mime’s techniques of body language and gesture. A good drawing or a good scene of animation should be easily “read” even without the props, background, and dialog.

The mime uses gestures, he uses attitudes of the body, and he uses illusion. Attitudes of the body suggest what the character is feeling. The mime has to show more than one thing: what the character is like, how he is involved, his traits, his environment, and what is motivating him. For instance, the attitude of his body should display what is going on in his mind by basic, universal gestural suggestions. The audience sympathizes with the actor because they recognize and understand (clearly) the gesture. The mime “magnifies” the truth — he doesn’t just exaggerate. This is an interesting concept, for we animators think of exaggeration when we caricature a character or an action. “Magnify” seems to be less mechanical, less surface adjustment. Character and feeling and ideas are from deep within, they are the truth of the character and therefore to magnify their truth seems more completely expressive.

In the olden days they used tableaus instead of acting out the scenes. Everything had to be “right on” to express what was going on (the story). There is a similar requirement for making a still drawing. It has to be “right on” or the meaning is lost. What worse fate can you think of than to have no meaning.

Ken acted out a character that comes on stage and is startled by something. He described with the body and facial expression that he was scared. Part of him wants to leave, post haste, and part of him is curious and wants to stay and see what it is. This is called an opposition.

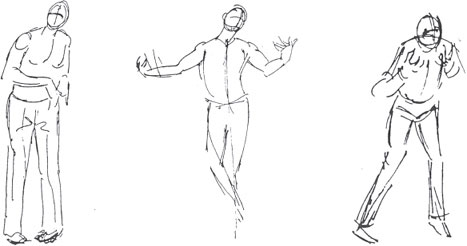

There are three great orders of movement the body is capable of doing.

1. There are oppositions where two parts of the body are trying to go in different directions at the same time. No sign of stress or stretch can be shown without them.

2. Then there are parallel moves (parallelisms), two parts go in the same direction, not necessarily a strong movement, but (sometimes) decorative.

3. Then there are successive movements where one part follows another. In animation this would be called overlapping action.

He said the strongest thing a mime can show on the stage is a straight line. Take a straight line and bend it — all kinds of things begin to happen — feelings and ideas are suggested.

The mime has to show two kinds of energy, inner and outside. These are forces that are manufactured inside the body, and forces that control his body from the outside. The mime has to understand where the source of energy is coming from to be truthful to it.

Francis Delsarte (The Delsarte Method) said the body is divided into three basic centers. First the intellect, (the head) where all the intellectual energy goes to and comes from. (By gestures we can tell when someone is thinking.) The torso is the emotional center containing aesthetics, feelings, falling in love, etc. Energy flows out from that area. The physical center is in the hips and pelvis area and from there down. Gut feelings, sexual feelings, and anger are expressed with that area.

Even random parts of the body seem to express certain emotions. For instance, the insides of the arms are the emotional parts of the arms. Those are what you expose when praying or when you embrace a loved one. The elbows and shoulders are the more aggressive parts. Delsarte said the shoulders and the elbows are the thermometer of the will. The eyes are the emotional part of the head; the mouth and lower jaw are the physical parts.

Delsarte categorizes not only the gestures of the body, but also the space around the body. We as artists are also concerned with the space around the body — not just the silhouette, but the third dimensional space that in a real sense becomes the boundaries within which our characters act. We, like the mime, use body language and gesture to illustrate our stories, but we have to create the illusion of depth — something the mime is blessed with by merely being on the stage.

Drawings courtesy of Ed Gutierrez.