We were most fortunate and privileged to have Judith Harding, mime and storyteller, for our model recently. It was very stimulating to see how she was able to do in her posing, things that animators are constantly called upon to do. “With a flick of the wrist,” as the old saying goes, but actually with all parts of her mind and body, she displayed truly classical ballet poses, traditional and abstract mime poses, and demonstrated her new art form — telling stories, using body gestures. She could also switch to a bashful, comical, almost “cutsey” character. It gave us a chance to study all of those styles in one evening.

Judith is well acquainted with the solid/flexible make-up of the body. She would turn her chest area to the right, her head to the left, lean her body one way, and tilt her head the other way, while her feet seemed to be walking away from it all. For that, she used the term, “opposition” — things working against each other causing a feeling of movement, life, and conflict. But hear! Conflict does not mean, necessarily, strife or warfare. Even a pose in the attitude of prayer can contain opposition. The face and eyes pointed hopefully to heaven, while the hands push downward at the end of straight, tense arms, seeming to signify a rejection of earth and all it stands for. Opposition in a pose tells us that the person is living, thinking, and deciding — wrestling with a problem, real or fictitious. There has to be options or there can be no life.

In animation, a classic example of opposing forces is “anticipation.” When a character wants to rush off stage to the right, he first leans to the left to gather his forces, holds it until the audience gets the picture, then he zips off in the opposite direction. That’s opposition in a linear sense. It accents the move. A still drawing can have movement too, if it contains some opposition.

For example, when a hip is protruding, it’s because it is being thrust out in opposition to the centerline of the body. Feel that thrust as you draw it. Don’t think of it as a hip just sticking out — think of it as a hip thrust out there by the character in the drawing. There must be some indication that it took some conscious, physical effort to get that hip out there. Make the hip look so much like it is being thrust out, that your viewers will inadvertently shift their hip — like when you yawn and someone sees you they yawn, too. Here are some suggestions I made in class in regards to thrusting the hips out. The rule applies to every part of the body like the neck, shoulders, elbows, knees, feet, even the eyes, nose, ears, etc.

When people see a good actor doing his thing, they may be unskilled in the art of gesture, but will know what is being portrayed and will be able to empathize with the actor. To a degree, they experience the gestures vicariously, feeling it is actually happening to them. In drawing you have to convince the audience they are experiencing the meaning of that pose, so they will say, “Oh, that’s great,” because through your skill you have persuaded them to enter into it as a personal experience. It allows everyone to get involved.

Georgia O’Keefe felt “invaded” because her works were misunderstood. “Critics wrote their own fixations or autobiographies into hers” (quoted from her current exhibit catalog). And because of that she did make an attempt to be a little more objective in her paintings. Abstract art is subject to personal interpretation and that is one of the charming things about it. In animation there is little room for the abstract. The audience must get the artwork pretty well interpreted for them by the artist or it will be hard for them to follow the story. Even the gestures that we recognize as “universal” vary from culture to culture, so a thorough study and knowledge of body language is indispensable for animation artists. I think that is one of the fun things about drawing — capturing a clear depiction of a gesture. When I paint abstracts or write certain kinds of poetry, I try to leave much room for multiple interpretations, but when sketching or drawing, I try to “go for the throat.”

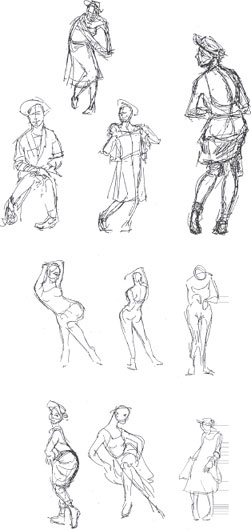

I confiscated a few sketches of Judith from Roger Chiasson and James Fujii, which are reproduced here in that order. Their techniques are different but each artist captured the poses well. A good model helps in that respect, inspiring artists to bring out the best in themselves. The ability is there, a good model just helps you prove it.

P.S. At the expense of being accused of “overkill,” allow me to explain the verb thrust, not in an “English” sense, but in a “drawing” sense. It means “to push with sudden force,” or “continuous pressure” (Webster). There is an overtone of movement suggested. A drawing should have that overtone in it. Go back to the drawings made by Roger and James and study them for opposition and thrust. Notice how the hips are thrust out, even when they are hidden behind clothing. Notice how some heads have been thrust out, up, or down. Go through them again and check the elbows for thrust — notice how the elbows work against each other (opposition). Check out the knees. In many instances they are forced together. When that happens, there is a tendency for the heel to be (‘scuse me — here it is again) thrust out. When the legs are spread apart, the toe has a tendency to thrust itself out farther. Notice how when the left knee is pushed to the right the face looks in the opposite direction. These are excellent poses and they are excellent drawings.