In Alexander Dobkin’s book Principles of Figure Drawing, there is a chapter on methods of drawing. He begins the chapter by suggesting that by experimenting with different ways of drawing, you will learn which way is best for you. He suggests, however, that no “good artist” abandons all other methods after choosing one particular way, for he may find different methods will be appropriate for different needs or problems. He also suggests that artists are always searching for a better way of saying what they mean. Dobkin lists four methods:

1. Contour drawing. It outlines the form in line. He says the beauty of this method is in its spontaneity. There are no erasures or renderings.

2. Rapid indication of form. I’m going to quote him in full here because it is my belief that this method is most suitable for animation. “Rapid indication of form involves a different kind of observation. Here the artist observes the main direction of a body and indicates it as completely as he can. He then goes back and finishes every part to his satisfaction, taking his time (well…not too much time), for even if the model can no longer hold her pose or is no longer there, the lines of her movement have already been indicated.” I interpret the “different kind of observation” to be the kind we are striving for in class — the ability to see action/gesture in our minds before we start to draw. In the drawing class, I call this “getting a good first impression.” Most of my “handouts” and class suggestions have to do with this approach.

3. Finishing one part at a time. Here the artist usually starts with the head, finishing it before going on to another part of the body. He suggests, but I don’t wish you to be tempted by this, that this is the best way to work from the model. However, he says, many artists feel this method teaches the artist to be careful and observant. So perhaps there is merit in it for study purposes.

Let me suggest, since you have to start somewhere, to start with the body, for the body is the foundation upon which all the appendages are attached and are dependent upon for positioning. If you locate the body, gesture-wise, you have somewhere to connect the neck, arms, and legs, eliminating the need to shift the foundation because you built the kitchen too far to the west.

4. Trial-and error-method. This is enjoyed by the largest number of artists. But this is for the artist who does not have a prerequisite, an idea of what he wants to end up with. “The drawing glides along,” Dobkin says, “and is conditioned partly by the artist’s concept, which may be incompletely formulated, and partly by what he already has on the paper. Often the lines themselves will suggest an entirely different picture from the original conceived in one’s mind…. It’s worth lies primarily in the possibilities it opens up for inventiveness and experimentation.”

In working from the model (and I would add sketching) there is a danger of becoming dependent on it. Also it may stifle the imagination. On the other hand, the artist who refuses to “look at reality” is apt to formalize or stylize his way of seeing and drawing. The solution to that problem is to practice both methods. I think a judicial blend of all these methods will keep us “on our toes.” But certainly, since in animation there is a preconceived story that you have to illustrate, you can’t rely on a method that arrives at drawings through happenstance. Actually, I don’t recommend getting too involved in methods of drawing. I think if you can form a good concept of what you want to portray then it will suggest the means to its accomplishment.

Here are some drawings from the last drawing class that may help us explore some of these points.

This is a drawing of an artist’s concept of what a hat looks like on a man’s head. It was a preconceived idea. He had seen hundreds of heads with hats on them and this is how he learned to see them. However, the model had pulled his hat lower down than “usual” or “normal” so that it became a gesture. The practice of drawing something the way you have learned to see it from past observation can sometimes be stifling. You may end up with an anatomy chart or a blueprint. That’s okay for study purposes, but when drawing gesture you are in another element, one that transcends “normal” left-brain knowledge. You have to think gesture, think caricature, think exaggeration, think of manipulating the study chart into an expressive gesture.

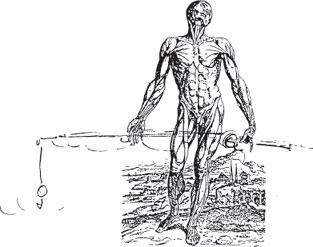

Here is another drawing where the artist is obviously intrigued with muscles and human structure. He was so enamored with the facts of anatomy that he neglected to interpret the pose. He may not be a person who goes around straightening pictures on walls, but he certainly straightened up this pose and made an anatomical chart out of it:

Here are two views of the same pose. Both artists seemed to have been more involved with the parts of the body than the gesture. Again, there is a tendency to straighten things up and a fear of using angles. I used very little so-called anatomy in my sketch but concentrated on having the figure lean on something. With that information, I can check the anatomy books later for details, if necessary, but there is not really enough gestural information in those other sketches to finish off the drawing at a later date.

A gesture drawing should go all the way. You have to look for squashes and stretches, angles, tensions, balance, silhouette, overall shape, dramatics, and especially, directing attention to the center of interest.

If you are going fishing, you’ll have to get the hook and bait out where the fish are, no matter what shape you’re in.

You won’t catch any fish acting like an anatomy chart.