5 Designing Marketing Programs to Build Brand Equity

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

-

Identify some of the new perspectives and developments in marketing.

-

Describe how marketers enhance product experience.

-

Explain the rationale for value pricing.

-

List some of the direct and indirect channel options.

-

Summarize the reasons for the growth in private labels.

Part of John Deere’s success is its well-conceived and executed product, pricing, and channel strategies.

Source: Eric Schlegel/The New York Times/Redux Pictures

Preview

This chapter considers how marketing activities in general—and product, pricing, and distribution strategies in particular—build brand equity. How can marketers integrate these activities to enhance brand awareness, improve the brand image, elicit positive brand responses, and increase brand resonance?

Our focus is on designing marketing activities from a branding perspective. We’ll consider how the brand itself can be effectively integrated into the marketing program to create brand equity. Of necessity, we leave a broader perspective on marketing activities to basic marketing management texts.1 We begin by considering some key developments in designing marketing programs. After reviewing product, pricing, and channel strategies, we conclude by considering private labels in Brand Focus 5.0.

New Perspectives on Marketing

The strategy and tactics behind marketing programs have changed dramatically in recent years as firms have dealt with enormous shifts in their external marketing environments. As outlined in Chapter 1, changes in the economic, technological, political–legal, sociocultural, and competitive environments have forced marketers to embrace new approaches and philosophies. Some of these changes include:2

-

Rapid technological developments

-

Greater customer empowerment

-

Fragmentation of traditional media

-

Growth of interactive and mobile marketing options

-

Channel transformation and disintermediation

-

Increased competition and industry convergence

-

Globalization and growth of developing markets

-

Heightened environmental, community, and social concerns

-

Severe economic recession

These changes, and others such as privatization and regulation, have combined to give customers and companies new capabilities with a number of implications for the practice of brand management (see Figure 5-1). Marketers are increasingly abandoning the mass-market strategies that built brand powerhouses in the twentieth century to implement new approaches for a new marketing era. Even marketers in staid, traditional categories and industries are rethinking their practices and not doing business as usual.

Consumers

Can wield substantially more customer power.

Can purchase a greater variety of available goods and services.

Can obtain a great amount of information about practically anything.

Can more easily interact with marketers in placing and receiving orders.

Can interact with other consumers and compare notes on products and services.

Companies

Can operate a powerful new information and sales channel with augmented geographic reach to inform and promote their company and its products.

Can collect fuller and richer information about their markets, customers, prospects, and competitors.

Can facilitate two-way communication with their customers and prospects, and facilitate transaction efficiency.

Can send ads, coupons, promotion, and information by e-mail to customers and prospects who give them permission.

Can customize their offerings and services to individual customers.

Can improve their purchasing, recruiting, training, and internal and external communication.

Figure 5-1 The New Capabilities of the New Economy

CLIF Bar

Started in 1990 by avid cyclist Gary Erickson and named to honor his father, CLIF® Bar set out to offer a better-tasting energy bar with wholesome ingredients. With very little advertising support, it grew in popularity through the years via word-of-mouth and PR. The CLIF Bar product line also grew to include dozens of flavors and varieties, some formulated especially for kids and women, and for energy, healthy snacking, and sports nutrition. Behind CLIF Bar products is a strong socially and environmentally responsible corporate message. The company is active in its local community and known for its passionate employees, who are allowed to do volunteer work on company time. It uses extensive organic ingredients, relies on biodiesel-powered vehicles, and supports the constructions of farmer- and Native American–owned wind farm through carbon offsets. Its nontraditional marketing activities focus on athletic sponsorships and public events. To broaden its appeal, it launched its “Meet the Moment™”campaign in the summer of 2011, in which participants provided stories and photos of inspirational athletic adventures. The integrated marketing campaign featured a fully interactive Web site and mobile applications for iPhone and Android systems. All these marketing efforts have paid off: CLIF Bar was the number one breakaway brand in a survey by Forbes magazine and Landor Associates measuring brand momentum from 2006 to 2009.

CLIF Bar has adopted modern marketing practices to build a highly successful twenty-first-century brand.

Source: Clif Bar & Company

The new marketing environment of the twenty-first century has forced marketers to fundamentally change the way they develop their marketing programs. Integration and personalization, in particular, have become increasingly crucial factors in building and maintaining strong brands, as companies strive to use a broad set of tightly focused, personally meaningful marketing activities to win customers.

Integrating Marketing

In today’s marketplace, there are many different means by which products and services and their corresponding marketing programs can build brand equity. Channel strategies, communication strategies, pricing strategies, and other marketing activities can all enhance or detract from brand equity. The customer-based brand equity model provides some useful guidance to interpret these effects. One implication of the conceptualization of customer-based brand equity is that the manner in which brand associations are formed does not matter—only the resulting awareness and strength, favorability, and uniqueness of brand associations.

In other words, if a consumer has an equally strong and favorable brand association from Rolaids antacids to the concept “relief,” whether it’s based on past product experiences, a Consumer Reports article, exposure to a “problem-solution” television ad that concludes with the tag line “R-O-L-A-I-D-S spells relief,” or knowledge that Rolaids has sponsored the “Rolaids Relief Man of the Year” award to the best relief pitchers in major league baseball since 1976, the impact in terms of customer-based brand equity should be identical unless additional associations such as “advertised on television” are created, or existing associations such as “speed or potency of effects” are affected in some way.3

Thus, marketers should evaluate all possible means to create knowledge, considering not just efficiency and cost but also effectiveness. At the center of all brand-building efforts is the actual product or service. Marketing activities surrounding that product, however, can be critical, as is the way marketers integrate the brand into them.

Consistent with this view, Schultz, Tannenbaum, and Lauterborn conceptualize one aspect of integrated marketing, integrated marketing communications, in terms of contacts.4 They define a contact as any information-bearing experience that a customer or prospect has with the brand, the product category, or the market that relates to the marketer’s product or service. According to these authors, a person can come in contact with a brand in numerous ways:

For example, a contact can include friends’ and neighbors’ comments, packaging, newspaper, magazine, and television information, ways the customer or prospect is treated in the retail store, where the product is shelved in the store, and the type of signage that appears in retail establishments. And the contacts do not stop with the purchase. Contacts also consist of what friends, relatives, and bosses say about a person who is using the product. Contacts include the type of customer service given with returns or inquiries, or even the types of letters the company writes to resolve problems or to solicit additional business. All of these are customer contacts with the brand. These bits and pieces of information, experiences, and relationships, created over time, influence the potential relationship among the customer, the brand, and the marketer.

In a similar vein, Chattopadhyay and Laborie develop a methodology for managing brand experience contact points.5

The bottom line is that there are many different ways to build brand equity. Unfortunately, there are also many different firms attempting to build their brand equity in the marketplace. Creative and original thinking is necessary to create fresh new marketing programs that break through the noise in the marketplace to connect with customers. Marketers are increasingly trying a host of unconventional means of building brand equity.

Moosejaw Mountaineering

Targeting a young college-age demographic, offbeat outdoor apparel and gear retailer Moosejaw Mountaineering has found success with a marketing strategy it calls “Love the Madness.” Founded by two former wilderness guides, the company has adopted the motto, “We sell the best outdoor gear in the world and have the most fun doing it.” Selling most major brands of snowboarding, rock climbing, hiking, and camping products—as well as its own private label—through nine stores in Michigan, Illinois, Colorado, and Massachusetts as well as a catalog and Web site, the retailer succeeds because of the way it sells. Virtually any consumer touchpoint with Moosejaw has an irreverent side. As co-founder Robert Wolfe says, “We have the great product, but then we put some stupid little twist to it that makes us stand out from everybody else.” In Moosejaw’s “Operation Sale,” store customers were invited to play the old electronic board game at checkout. Picking up the charley horse without setting off the buzzer brought the customer 20 percent off! The company launched a “Break-Up Service” in which it volunteered to make the difficult call to help customers seeking to end relationships. Text messages from the store offer discounts for replies. One text challenged customers to a digital version of the popular “Rock, Paper, Scissors” game with a 20 percent discount for winners. When the company added a single line to its catalog asking readers to send their best illustration of “crying tomatoes,” 300 people replied. All these different efforts have had a payoff: company market research shows that the 40 percent of customers who can be classified as “highly engaged” with the brand place at least four orders with the company, more than the norm.6

Moosejaw Mountaineering’s unconventional branding approach has created much engagement and loyalty with customers.

Source: Moosejaw Mountaineering

Creativity must not sacrifice a brand-building goal, however, and marketers must orchestrate programs to provide seamlessly integrated solutions and personalized experiences for customers that create awareness, spur demand, and cultivate loyalty.

Personalizing Marketing

The rapid expansion of the Internet and continued fragmentation of mass media have brought the need for personalized marketing into sharp focus. Many maintain that the modern economy celebrates the power of the individual consumer. To adapt to the increased consumer desire for personalization, marketers have embraced concepts such as experiential marketing and relationship marketing.

Experiential Marketing

Experiential marketing promotes a product by not only communicating a product’s features and benefits but also connecting it with unique and interesting consumer experiences. One marketing commentator describes experiential marketing this way: “The idea is not to sell something, but to demonstrate how a brand can enrich a customer’s life.”7

Pine and Gilmore, pioneers on the topic, argued over a decade ago that we are on the threshold of the “Experience Economy,” a new economic era in which all businesses must orchestrate memorable events for their customers.8 They made the following assertions:

-

If you charge for stuff, then you are in the commodity business.

-

If you charge for tangible things, then you are in the goods business.

-

If you charge for the activities you perform, then you are in the service business.

-

If you charge for the time customers spend with you, then and only then are you in the experience business.

Citing a range of examples from Disney to AOL, they maintain that saleable experiences come in four varieties: entertainment, education, aesthetic, and escapist.

Columbia University’s Bernd Schmitt, another pioneering expert on the subject, notes that “experiential marketing is usually broadly defined as any form of customer-focused marketing activity, at various touchpoints, that creates a sensory-emotional connection to customers.”9 Schmitt details five different types of marketing experiences that are becoming increasingly vital to consumers’ perceptions of brands:

-

Sense marketing appeals to consumers’ senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell).

-

Feel marketing appeals to customers’ inner feelings and emotions, ranging from mildly positive moods linked to a brand (e.g., for a noninvolving, nondurable grocery brand or service or industrial product) to strong emotions of joy and pride (e.g., for a consumer durable, technology, or social marketing campaign).

-

Think marketing appeals to the intellect in order to deliver cognitive, problem-solving experiences that engage customers creatively.

-

Act marketing targets physical behaviors, lifestyles, and interactions.

-

Relate marketing creates experiences by taking into account individuals’ desires to be part of a social context (e.g., to their self-esteem, being part of a subculture, or a brand community).

Victoria’s Secret has been praised for its success in creating an experiential brand.

Source: Louis Johnny/SIPA/Newscom

He also describes how various “experience providers” (such as communications, visual/verbal identity and signage, product presence, co-branding, spatial environments, electronic media, and salespeople) can become part of a marketing campaign to create these experiences. In describing the increasingly more demanding consumer, Schmitt writes, “Customers want to be entertained, stimulated, emotionally affected and creatively challenged.”

Figure 5-2 displays a scale developed by Schmitt and his colleagues to measure experiences and its dimensions. Their study respondents rated LEGO, Victoria’s Secret, iPod, and Starbucks as the most experiential brands.10

Meyer and Schwager describe a customer experience management (CEM) process that involves monitoring three different patterns: past patterns (evaluating completed transactions), present patterns (tracking current relationships), and potential patterns (conducting inquiries in the hope of unveiling future opportunities).11 The Science of Branding 5-1 describes how some marketers are thinking more carefully about one particularly interesting aspect of brand experiences—brand scents!

Relationship Marketing

Marketing strategies must transcend the actual product or service to create stronger bonds with consumers and maximize brand resonance. This broader set of activities is sometimes called relationship marketing and is based on the premise that current customers are the key to long-term brand success.12 Relationship marketing attempts to provide a more holistic, personalized brand experience to create stronger consumer ties. It expands both the depth and the breadth of brand-building marketing programs.

SENSORY |

This brand makes a strong impression on my visual sense or other senses. I find this brand interesting in a sensory way. This brand does not appeal to my senses. |

AFFECTIVE |

This brand induces feelings and sentiments. I do not have strong emotions for this brand. This brand is an emotional brand. |

BEHAVIORAL |

I engage in physical actions and behaviors when I use this brand. This brand results in bodily experiences. This brand is not action oriented. |

INTELLECTUAL |

I engage in a lot of thinking when I encounter this brand. This brand does not make me think. This brand stimulates my curiosity and problem solving. |

Figure 5-2 Brand Experience Scale

Source: Based on J. Joško Brakus, Bernd H. Schmitt, and Lia Zarantonello, “Brand Experience: What Is It? How Is It Measured? Does It Affect Loyalty?,” Journal of Marketing 73 (May 2009): 52–68.

Here are just a few of the basic benefits relationship marketing provides:13

-

Acquiring new customers can cost five times as much as satisfying and retaining current customers.

-

The average company loses 10 percent of its customers each year.

-

A 5 percent reduction in the customer defection rate can increase profits by 25–85 percent, depending on the industry.

-

The customer profit rate tends to increase over the life of the retained customer.

We next review three concepts that can be helpful with relationship marketing: mass customization, one-to-one marketing, and permission marketing.

Mass Customization

The concept behind mass customization, namely making products to fit the customer’s exact specifications, is an old one, but the advent of digital-age technology enables companies to offer customized products on a previously unheard-of scale. Going online, customers can communicate their preferences directly to the manufacturer, which, by using advanced production methods, can assemble the product for a price comparable to that of a noncustomized item.

In an age defined by the pervasiveness of mass-market goods, mass customization enables consumers to distinguish themselves with even basic purchases. The online jeweler Blue Nile lets customers design their own rings. Custom messenger-bag maker Rickshaw Bagworks lets customers design their own bags before they are made to order. Sportswear vendor Shortomatic lets customers upload their own images and overlay them on a pair of custom-designed shorts. Land’s End also allows customization of certain styles of pants and shirts on its Web site to allow for a better fit.14

Mass customization is not restricted to products. Many service organizations such as banks are developing customer-specific services and trying to improve the personal nature of their service experience with more service options, more customer-contact personnel, and longer service hours.15

Mass customization can offer supply-side benefits too. Retailers can reduce inventory, saving warehouse space and the expense of keeping track of everything and discounting leftover merchandise.16 Mass customization has its limitations, however, because not every product is easily customized and not every product demands customization. Returns are also more problematic for a customized product that may not have broader appeal.

With the advent of social media, customers can now share with others what they have co-created with firms. For example, Nike enables customers to put their own personalized message on a pair of shoes with the NIKEiD program. At the NIKEiD Web site, visitors can make a customized shoe by selecting the size, width, and color scheme and affixing an eight-character personal ID to their creation. Then they can share it with others for them to admire.17

One-to-One Marketing

Don Peppers and Martha Rogers popularized the concept of one- to-one marketing, an influential perspective on relationship marketing.18 The basic rationale is that consumers help add value by providing information to marketers; marketers add value, in turn, by taking that information and generating rewarding experiences for consumers. The firm is then able to create switching costs, reduce transaction costs, and maximize utility for consumers, all of which help build strong, profitable relationships.

One-to-one marketing is thus based on several fundamental strategies:

-

Focus on individual consumers through consumer databases—“We single out consumers.”

-

Respond to consumer dialogue via interactivity—“The consumer talks to us.”

-

Customize products and services—“We make something unique for him or her.”

Another tenet of one-to-one marketing is treating different consumers differently because of their different needs, and their different current and future value to the firm. In particular, Peppers and Rogers stress the importance of devoting more marketing effort to the most valuable consumers.

With NIKEiD, customers can customize their shoes and share their creations with others online.

Source: Getty Images/Getty Images for Nike

Peppers and Rogers identified several examples of brands that have practiced one-to-one marketing through the years, such as Avon, Owens-Corning, and Nike.19 They note how Ritz-Carlton hotels use databases to store consumer preferences, so that if a customer makes a special request in one of its hotels, it is already known when he or she stays in another.

Peppers and Rogers also provide an example of a localized version of one-to-one marketing. After having ordered flowers at a local florist for his or her mother, a customer might receive a postcard “reminding him that he had sent roses and star lilies last year and that a phone call would put a beautiful arrangement on her doorstep again for her birthday this year.” Although such online or offline reminders can be helpful, marketers must not assume that customers always want to repeat their behaviors. For example, what if the flowers were a doomed, last-chance attempt to salvage a failing relationship? Then a reminder under such circumstances may not be exactly welcome!

An example of a highly successful relationship marketing program comes from Tesco, the United Kingdom’s largest grocer.

Tesco

Celebrating its fifteenth anniversary in 2010, Tesco Clubcard is one of the world’s most successful retail loyalty schemes. Each of the 10 million members in the program has a unique “DNA profile” based on the products he or she buys. Products themselves are classified on up to 40 dimensions—such as package size, healthy, own label, ecofriendly, ready-to-eat, and so on—to facilitate this customer categorization. In exchange for providing their purchase information and basic demographic information, members receive a variety of purchase benefits across a wide range of products and services beyond what is sold in their stores. Tracking customers’ purchases in the program, in turn, helps Tesco uncover price elasticities, offer targeted promotions, and improve marketing efficiency. By also strengthening customer loyalty, the Clubcard program has been estimated to generate cumulative savings to Tesco of over £350 million. The range of products, the nature of merchandising, and even the location of Tesco’s convenience stores all benefit from the use of this customer data to develop tailored solutions. Tesco has introduced a number of Clubcard program innovations through the years, including key fobs and newly designed cards issued in 2008.20

Tesco’s Clubcard is the centerpiece of one of the world’s most successful retail loyalty programs.

Source: Tesco Stores Ltd.

Permission Marketing

Permission marketing, the practice of marketing to consumers only after gaining their express permission, was another influential perspective on how companies can break through the clutter and build customer loyalty. A pioneer on the topic, Seth Godin, has noted that marketers can no longer employ “interruption marketing” or mass media campaigns featuring magazines, direct mail, billboards, radio and television commercials, and the like, because consumers have come to expect—but not necessarily appreciate—these interruptions.21 By contrast, Godin asserts, consumers appreciate receiving marketing messages they gave permission for: “The worse the clutter gets, the more profitable your permission marketing efforts become.”

Given the large number of marketing communications that bombard consumers every day, Godin argues that if marketers want to attract a consumer’s attention, they first need to get his or her permission with some kind of inducement—a free sample, a sales promotion or discount, a contest, and so on. By eliciting consumer cooperation in this manner, marketers might develop stronger relationships with consumers so that they desire to receive further communications in the future. Those relationships will only develop, however, if marketers respect consumers’ wishes, and if consumers express a willingness to become more involved with the brand.22

With the help of large databases and advanced software, companies can store gigabytes of customer data and process this information in order to send targeted, personalized marketing e-mail messages to customers. Godin identifies five steps to effective permission marketing:

-

Offer the prospect an incentive to volunteer.

-

Offer the interested prospect a curriculum over time, teaching the consumer about the product or service being marketed.

-

Reinforce the incentive to guarantee that the prospect maintains his or her permission.

-

Offer additional incentives to get more permission from the consumer.

-

Over time, leverage the permission to change consumer behavior toward profits.

In Godin’s view, effective permission marketing works because it is “anticipated, personal, and relevant.” A recent consumer research study provides some support: 87 percent of respondents agreed that e-mail “is a great way for me to hear about new products available from retail companies”; 88 percent of respondents said a retailer’s e-mail has prompted them to download/print out a coupon; 75 percent said it has led them to buy a product online; 67 percent said it has prompted an offline purchase; and 60 percent have been moved to “try a new product for the first time.”23 Amazon.com has successfully applied permission marketing on the Web for years.24

Amazon

With customer permission, online retailer Amazon uses database software to track its customers’ purchase habits and send them personalized marketing messages. Each time a customer purchases something from Amazon.com, he or she can receive a follow-up e-mail containing information about other products that might interest him or her based on that purchase. For example, if a customer buys a book, Amazon might send an e-mail containing a list of titles by the same author, or of titles also purchased by customers who bought the original title. With just one click, the customer can get more detailed information. Amazon also sends periodic e-mails to customers informing them of new products, special offers, and sales. Each message is tailored to the individual customer based on past purchases and specified preferences, according to customer wishes. Amazon keeps an exhaustive list of past purchases for each customer and makes extensive recommendations.

Permission marketing is a way of developing the “consumer dialogue” component of one-to-one marketing in more detail. One drawback to permission marketing, however, is that it presumes that consumers have some sense of what they want. In many cases, consumers have undefined, ambiguous, or conflicting preferences that might be difficult for them to express. Thus, marketers must recognize that consumers may need to be given guidance and assistance in forming and conveying their preferences. In that regard, participation marketing may be a more appropriate term and concept to employ, because marketers and consumers need to work together to find out how the firm can best satisfy consumer goals.25

Reconciling the Different Marketing Approaches

These and other different approaches to personalization help reinforce a number of important marketing concepts and techniques. From a branding point of view, they are particularly useful means of both eliciting positive brand responses and creating brand resonance to build customer-based brand equity. Mass customization and one-to-one and permission marketing are all potentially effective means of getting consumers more actively engaged with a brand.

According to the customer-based brand equity (CBBE) model, however, these different approaches emphasize different aspects of brand equity. For example, mass customization and one-to-one and permission marketing might be particularly effective at creating greater relevance, stronger behavioral loyalty, and attitudinal attachment. Experiential marketing, on the other hand, would seem to be particularly effective at establishing brand imagery and tapping into a variety of different feelings as well as helping build brand communities. Despite potentially different areas of emphasis, all four approaches can build stronger consumer–brand bonds.

One implication of these new approaches is that the traditional “marketing mix” concept and the notion of the “4 Ps” of marketing—product, price, place (or distribution), and promotion (or marketing communications)—may not fully describe modern marketing programs, or the many activities, such as loyalty programs or pop-up stores, that may not necessarily fit neatly into one of those designations. Nevertheless, firms still have to make decisions about what exactly they are going to sell, how (and where) they are going to sell it, and at what price. In other words, firms must still devise product, pricing, and distribution strategies as part of their marketing programs.

The specifics of how they set those strategies, however, have changed considerably. We turn next to these topics and highlight a key development in each area, recognizing that there are many other important areas beyond the scope of this text. With product strategy, we emphasize the role of extrinsic factors; with pricing strategy, we focus on value pricing; and with channel strategy, we concentrate on channel integration.

Product Strategy

The product itself is the primary influence on what consumers experience with a brand, what they hear about a brand from others, and what the firm can tell customers about the brand. At the heart of a great brand is invariably a great product.

Designing and delivering a product or service that fully satisfies consumer needs and wants is a prerequisite for successful marketing, regardless of whether the product is a tangible good, service, or organization. For brand loyalty to exist, consumers’ experiences with the product must at least meet, if not actually surpass, their expectations.

After considering how consumers form their opinions of the quality and value of a product, we consider how marketers can go beyond the actual product to enhance product experiences and add additional value before, during, and after product use.

Perceived Quality

Perceived quality is customers’ perception of the overall quality or superiority of a product or service compared to alternatives and with respect to its intended purpose. Achieving a satisfactory level of perceived quality has become more difficult as continual product improvements over the years have led to heightened consumer expectations.26

Much research has tried to understand how consumers form their opinions about quality. The specific attributes of product quality can vary from category to category. Nevertheless, consistent with the brand resonance model from Chapter 2, research has identified the following general dimensions: primary ingredients and supplementary features; product reliability, durability and serviceability; and style and design.27 Consumer beliefs about these characteristics often define quality and, in turn, influence attitudes and behavior toward a brand.

Product quality depends not only on functional product performance but on broader performance considerations as well, like speed, accuracy, and care of product delivery and installation; the promptness, courtesy, and helpfulness of customer service and training; and the quality of repair service.

Brand attitudes may also depend on more abstract product imagery, such as the symbolism or personality reflected in the brand. These “augmented” aspects of a product are often crucial to its equity. Finally, consumer evaluations may not correspond to the perceived quality of the product and may be formed by less thoughtful decision making, such as simple heuristics and decision rules based on brand reputation or product characteristics such as color or scent.

Aftermarketing

To achieve the desired brand image, product strategies should focus on both purchase and consumption. Much marketing activity is devoted to finding ways to encourage trial and repeat purchases by consumers. Perhaps the strongest and potentially most favorable associations, however, result from actual product experience—what Procter & Gamble calls the “second moment of truth” (the “first moment of truth” occurs at purchase).

Unfortunately, too little marketing attention is devoted to finding new ways for consumers to truly appreciate the advantages and capabilities of products. Perhaps in response to this oversight, one notable trend in marketing is the growing role of aftermarketing, that is, those marketing activities that occur after customer purchase. Innovative design, thorough testing, quality production, and effective communication—through mass customization or any other means—are without question the most important considerations in enhancing product consumption experiences that build brand equity.

In many cases, however, they may only be necessary and not sufficient conditions for brand success, and marketers may need to use other means to enhance consumption experiences. Here we consider the role of user manuals, customer service programs, and loyalty programs.

User Manuals

Instruction or user manuals for many products are too often an afterthought, put together by engineers who use overly technical terms and convoluted language. Online help forums put the consumer at the mercy of other equally ignorant users or so-called experts who may not understand or appreciate the obstacles the average consumer faces.

As a result, consumers’ initial product experiences may be frustrating or, even worse, unsuccessful. Even if consumers are able to figure out how to make the product perform its basic functions, they may not learn to appreciate some of its more advanced features, which are usually highly desirable and possibly unique to the brand.

To enhance consumers’ consumption experiences, marketers must develop user manuals or help features that clearly and comprehensively describe both what the product or service can do for consumers and how they can realize these benefits. With increasing globalization, writing easy-to-use instructions has become even more important because they often require translation into multiple languages.28 Manufacturers are spending more time designing and testing instructions to make them as user friendly as possible.

User manuals increasingly may need to appear in online and multimedia formats to most effectively demonstrate product functions and benefits. Intuit, makers of the Quicken personal finance management software package, routinely sends researchers home with first-time buyers to check that its software is easy to install and to identify any sources of problems that might arise. Corel software adopts a similar “Follow Me Home” strategy and also has “pizza parties” at the company where marketing, engineering, and quality assurance teams analyze the market research together, so that marketing does not just hand down conclusions to other departments.29

Customer Service Programs

Aftermarketing, however, is more than the design and communication of product instructions. As one expert in the area notes, “The term ‘aftermarketing’ describes a necessary new mind-set that reminds businesses of the importance of building a lasting relationship with customers, to extend their lifetimes. It also points to the crucial need to better balance the allocation of marketing funds between conquest activities (like advertising) and retention activities (like customer communication programs).”30

Creating stronger ties with consumers can be as simple as creating a well-designed customer service department. Research by Accenture in 2010 found that two in three customers switched companies in the past year due to poor customer service.31 In the auto industry, after-sales service from the dealer is a critical determinant of loyalty and repeat buying of a brand. Routine maintenance and unplanned repairs are an opportunity for dealers to strengthen their ties with customers.32

Aftermarketing can include the sale of complementary products that help make up a system or in any other way enhance the value of the core product. Printer manufacturers such as Hewlett-Packard derive much of their revenue from high-margin postpurchase items such as ink-jet cartridges, laser toner cartridges, and paper specially designed for PC printers. The average owner of a home PC printer spends much more on consumables over the lifetime of the machine than on the machine itself.33

Aftermarketing can be an important determinant of profitability. For example, roughly three-quarters of revenue for aerospace and defense providers comes from aftermarket support and related sales. Aftermarket sales are strongest when customers are locked in to buying from the company that sold them the primary product due to service contracts, proprietary technology or patents, or unique service expertise.34

HP makes much more money selling printer cartridges than from selling the printer itself.

Source: Brown Adrian/SIPA/Newscom

Loyalty Programs

Loyalty or frequency programs have become one popular means by which marketers can create stronger ties to customers.35 Their purpose is “identifying, maintaining, and increasing the yield from a firm’s ‘best’ customers through long-term, interactive, value-added relationships.”36 Firms in all kinds of industries—most notably the airlines—have established loyalty programs through different mixtures of specialized services, newsletters, premiums, and incentives. Often they include extensive co-branding arrangements or brand alliances.

American Airlines

In 1981, American Airlines founded the first airline loyalty program, called AAdvantage. This frequent-flier program rewarded the airline’s top customers with free trips and upgrades based on mileage flown. By recognizing customers for their patronage and giving them incentives to bring their business to American Airlines, the airline hoped to increase loyalty among its passengers. The program was an instant success, and other airlines quickly followed suit. These days, members can earn miles at more than 1,000 participating companies, which include over 35 hotel chains representing more than 75 brands, more than 20 airlines, eight car rental companies, and approximately 25 major retail/financial companies. In addition, members can earn miles when making purchases with one of more than 60 affinity card products in 30 countries. Today, scores of frequent-traveler programs exist, but American Airlines is still one of the largest, with membership of over 67 million in 2011.37

Many businesses besides airlines introduced loyalty programs in the intervening years because they often yield results.38 As one marketing executive said, “Loyalty programs reduce defection rates and increase retention. You can win more of a customer’s purchasing share.” The value created by the loyalty program creates switching costs for consumers, reducing price competition among brands.

To get discounts, however, consumers must typically hand over personal data, raising privacy concerns. When the loyalty program is tied into a credit card, as is sometimes the case, privacy concerns are even more acute. Nevertheless, the lure of special deals can be compelling to consumers, and in 2011, there were more than 2 billion memberships in loyalty programs, with an average value of $622 points issues per household. A third of these rewards, however, remain unredeemed.39

The appeal to marketers is clear too. Fifteen percent of a retailer’s most loyal customers can account for as much as half its sales, and it can take between 12 and 20 new customers to replace a lost loyal customer.40 Some tips for building effective loyalty programs follow:41

-

Know your audience: Most loyalty marketers employ sophisticated databases and software to determine which customer segment to target with a given program. Target customers whose purchasing behavior can be changed by the program.

-

Change is good: Marketers must constantly update the program to attract new customers and prevent other companies in their category from developing “me-too” programs. “Any loyalty program that stays static will die,” said one executive.

-

Listen to your best customers: Suggestions and complaints from top customers deserve careful consideration, because they can lead to improvements in the program. Because they typically represent a large percentage of business, top customers must also receive better service and more attention.

-

Engage people: Make customers want to join the program. Make the program easy to use and offer immediate rewards when customers sign up. Once they become members, make customers “feel special,” for example, by sending them birthday greetings, special offers, or invitations to special events.

Summary

The product is at the heart of brand equity. Marketers must design, manufacture, market, sell, deliver, and service products in a way that creates a positive brand image with strong, favorable, and unique brand associations; elicits favorable judgments and feelings about the brand; and fosters greater degrees of brand resonance.

Product strategy entails choosing both tangible and intangible benefits the product will embody and marketing activities that consumers desire and the marketing program can deliver. A range of possible associations can become linked to the brand—some functional and performance-related, and some abstract and imagery-related. Perceived quality and perceived value are particularly important brand associations that often drive consumer decisions.

Because of the importance of loyal customers, relationship marketing has become a branding priority. Consequently, consumers’ actual product experiences and aftermarketing activities have taken on increased importance in building customer-based brand equity. Those marketers who will be most successful at building CBBE will take the necessary steps to make sure they fully understand their customers and how they can deliver superior value before, during, and after purchase. A company doing just that is CVS.

CVS

Drugstore chain leader CVS has taken a number of steps to ensure customer loyalty. Data from its ExtraCare loyalty program is used to tailor offerings to its 67 million plus members. Interactive ExtraCare Coupon Centers in the stores let shoppers scan their loyalty cards to receive targeted offers before checking out, based on past purchases. Coupon Centers can also check product prices and dispense ExtraBucks rewards. In addition to coupons, the program offers customers 2 percent cash back on every dollar spent. The company notes that the average purchase by ExtraCare customers is higher (averaging 4.5 items for $15) than by non-ExtraCare customers (averaging 3.6 items for $12). CVS’s rewards program set it apart from rival Walgreens, which did not originally have a loyalty card. Within five years, the ExtraCare card became associated with 60 percent of front-store transactions.42

CVS has found that its ExtraCare loyalty program creates more profitable customers.

Source: CVS

Pricing Strategy

Price is the one revenue-generating element of the traditional marketing mix, and price premiums are among the most important benefits of building a strong brand. This section considers the different kinds of price perceptions that consumers might form, and different pricing strategies that the firm might adopt to build brand equity.

Consumer Price Perceptions

The pricing strategy can dictate how consumers categorize the price of the brand (as low, medium, or high), and how firm or how flexible they think the price is, based on how deeply or how frequently it is discounted.

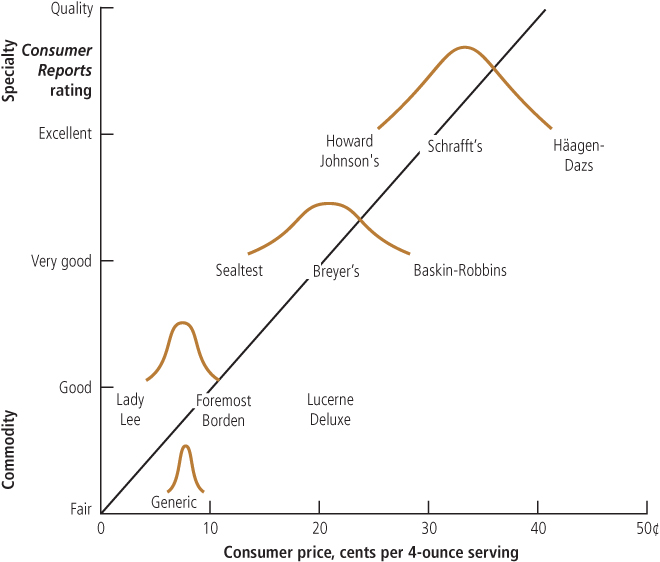

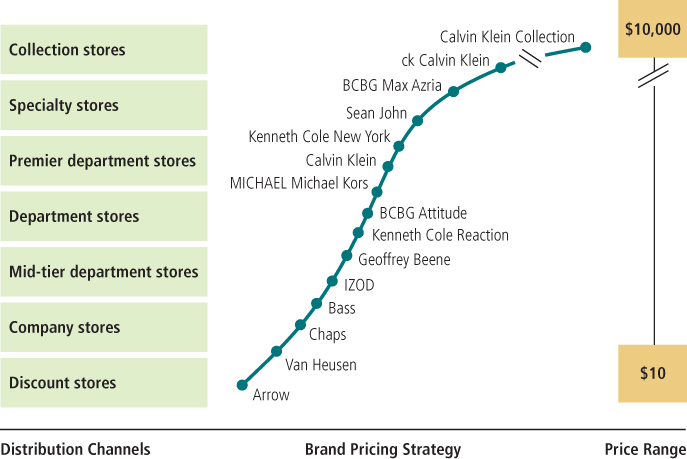

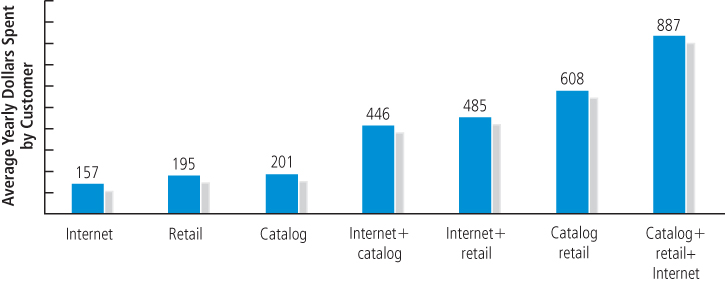

Consumers often rank brands according to price tiers in a category.43 For example, Figure 5-3 shows the price tiers that resulted from a study of the ice cream market.44 In that market, as the figure shows, there is also a relationship between price and quality. Within any price tier, there is a range of acceptable prices, called price bands, that indicate the flexibility and breadth marketers can adopt in pricing their brands within a tier. Some companies sell multiple brands to better compete in multiple categories. Figure 5-4 displays clothing offerings from Phillips Van Huesen that at one time covered a wide range of prices and corresponding retail outlets.45

Besides these descriptive “mean and variance” price perceptions, consumers may have price perceptions that have more inherent product meaning. In particular, in many categories, they may infer the quality of a product on the basis of its price and use perceived quality and price to arrive at an assessment of perceived value. Costs here are not restricted to the actual monetary price but may reflect opportunity costs of time, energy, and any psychological involvement in the decision that consumers might have.46

Consumer associations of perceived value are often an important factor in purchase decisions. Thus many marketers have adopted value-based pricing strategies—attempting to sell the right product at the right price—to better meet consumer wishes, as described in the next section.

In short, price has complex meaning and can play multiple roles to consumers. The Science of Branding 5-2 provides insight into how consumers perceive and process prices as part of their shopping behavior. Marketers need to understand all price perceptions that consumers have for a brand, to uncover quality and value inferences, and to discover any price premiums that exist.

Figure 5-3 Price Tiers in the Ice Cream Market

Figure 5-4 Phillips Van-Heusen Brand Price Tiers

Setting Prices to Build Brand Equity

Choosing a pricing strategy to build brand equity means determining the following:

-

A method for setting current prices

-

A policy for choosing the depth and duration of promotions and discounts

There are many different approaches to setting prices, and the choice depends on a number of considerations. This section highlights a few of the most important issues as they relate to brand equity.47

Factors related to the costs of making and selling products and the relative prices of competitive products are important determinants in pricing strategy. Increasingly, however, firms are placing greater importance on consumer perceptions and preferences. Many firms now are employing a value-pricing approach to setting prices and an everyday-low-pricing (EDLP) approach to determining their discount pricing policy over time. Let’s look at both.

Value Pricing

The objective of value pricing is to uncover the right blend of product quality, product costs, and product prices that fully satisfies the needs and wants of consumers and the profit targets of the firm. Marketers have employed value pricing in various ways for years, sometimes learning the hard way that consumers will not pay price premiums that exceed their perceptions of the value of a brand. Perhaps the most vivid illustration was the legendary price cut for Philip Morris’s leading cigarette brand, Marlboro, described in Branding Brief 5-1.48

Walmart’s “Save Money. Live Better” slogan succinctly summarizes its strong value positioning.

Source: Beth Hall/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Two important and enduring branding lessons emerged from the Marlboro episode. First, strong brands can command price premiums. Once Marlboro’s price entered a more acceptable range, consumers were willing to pay the still-higher price, and sales of the brand started to increase. Second, strong brands cannot command an excessive price premium. The clear signal sent to marketers everywhere is that price hikes without corresponding investments in the value of the brand may increase the vulnerability of the brand to lower-priced competition. In these cases, consumers may be willing to “trade down” because they no longer can justify to themselves that the higher-priced brand is worth it. Although the Marlboro price discounts led to short-term profitability declines, they also led to regained market share that put the brand on a stronger footing over the longer haul.

In today’s challenging new climate, several firms have been successful by adopting a value-pricing strategy. For example, Walmart’s slogan, “Save Money. Live Better,” describes the pricing strategy that has allowed it to become the world’s largest retailer. Southwest Airlines combined low fares with no-frills—but friendly—service to become a powerful force in the airline industry. The success of these and other firms has dramatized the potential benefits of implementing a value-pricing strategy.

As you might expect, there are a number of opinions regarding the keys for success in adopting a value-based pricing approach. In general, however, an effective value-pricing strategy should strike the proper balance among three key components:

-

Product design and delivery

-

Product costs

-

Product prices

In other words, as we’ve seen before, the right kind of product has to be made the right way and sold at the right price. We look at each of these three elements below. Meanwhile, a brand that has experienced much success in recent years balancing this formula is Hyundai.

Hyundai

Taking a page from the Samsung playbook, Korean upstart automaker Hyundai is trying to do to Toyota and Honda what Samsung successfully did to Sony—provide an affordable alternative to a popular market leader. Like Samsung, Hyundai has adopted a well-executed value pricing strategy that combines advanced technology, reliable performance, and attractive design with lower prices. As the head of U.S. design noted in discussing the 2011 Sonata sedan and revamped Tucson crossover, “The basic idea is a car that looks like a premium car, but not at a premium price. We’re looking to pull people out of Camrys and Accords and give them something different.” Hyundai’s 10-year or 100,000 mile power train warranty programs and positive reviews from car analysts such as J. D. Power provided additional reassurance to potential buyers of the quality of the products and the company’s stability. To maintain momentum during the recession, Hyundai’s “Assurance” program, featuring a highly publicized Super Bowl TV spot, allowed new buyers to return their Hyundai vehicles if they lost their job. All these efforts were met with greater customer acceptance: the number of potential U.S. buyers who say they would “definitely” consider a Hyundai tripled from 2000 to 2009. Hyundai’s current Assurance program is centered on a new Trade-in Value Guarantee that preserves the market value of a new Hyundai by guaranteeing to customers at the time of purchase exactly how much it would be worth, two, three, or four years from now.49

Hyundai has a strong value proposition, anchored by its 10-year or 100,000-mile warranty.

Source: Hyundai Motor America

Product Design and Delivery

The first key is the proper design and delivery of the product. Product value can be enhanced through many types of well-conceived and well-executed marketing programs, such as those covered in this and other chapters of the book . Proponents of value pricing point out that the concept does not mean selling stripped-down versions of products at lower prices. Consumers are willing to pay premiums when they perceive added value in products and services.

Some companies actually have been able to increase prices by skillfully introducing new or improved “value-added” products. Some marketers have coupled well-marketed product innovations and improvements with higher prices to strike an acceptable balance to at least some market segments. Here are two examples of Procter & Gamble brands that used that formula to find marketplace success in the midst of the deep recession of 2008–2010.

-

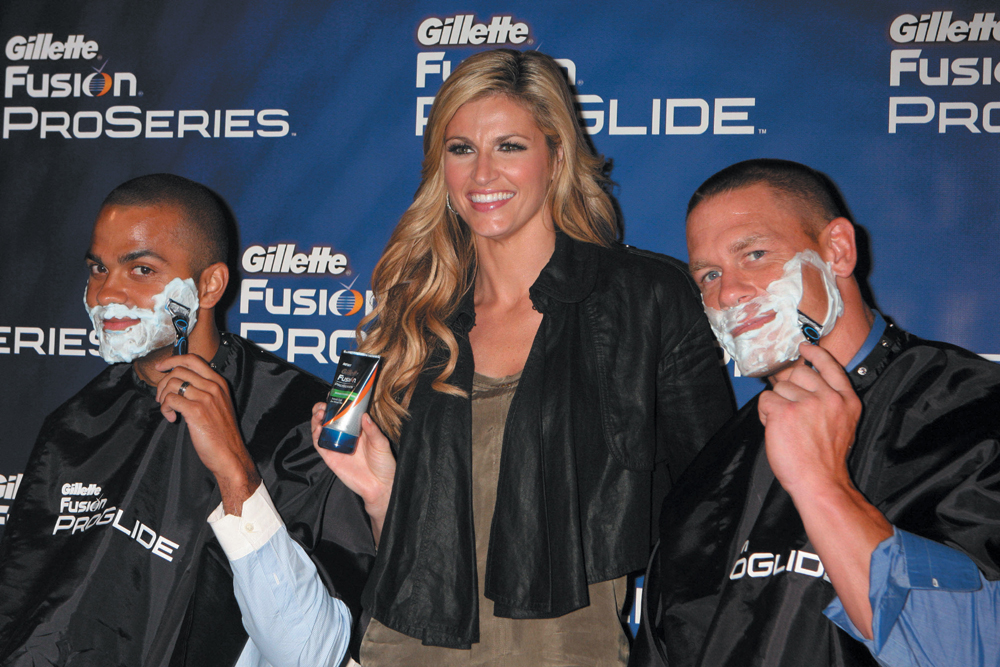

P&G introduced its most expensive Gillette razor ever, the Fusion ProGlide, by combining an innovative product with strong marketing support. Its “Turning Shaving into Gliding and Skeptics into Believers” campaign for Fusion ProGlide gave sample razors to bloggers and ran ads online and on TV showing men outside their homes given impromptu shaves with the new razor.50

-

P&G’s Pepto-Bismol stomach remedy liquid was able to command a 60 percent price premium over private labels through a blend of product innovation (new cherry flavors) and an engaging advertising campaign that broke copy-testing research records for the brand (“Coverage” featuring a headset-wearing, pink-vested “Pepto Guy” fielding calls and offering humorous advice to gastrointestinally challenged callers).51

With the advent of the Internet, many critics predicted that customers’ ability to perform extensive, assisted online searches would result in only low-cost providers surviving. In reality, the advantages of creating strong brand differentiation have led to price premiums when brands are sold online just as much as when sold offline. For example, although undersold by numerous book and music sellers online, Amazon.com was able to maintain market leadership, eventually forcing low-priced competitors such as Books.com and others out of business.52

Product Costs

The second key to a successful value-pricing strategy is to lower costs as much as possible. Meeting cost targets invariably requires finding additional cost savings through productivity gains, outsourcing, material substitution (less expensive or less wasteful materials),

Famous athletes and celebrities—such as NBA player Tony Parker, WWE wrestler John Cena, and TV sportscaster Erin Andrews—have promoted Gillette’s latest Fusion ProGlide razor and its innovative performance features.

Source: mZUMA Press/Newscom

product reformulations, and process changes like automation or other factory improvements.53 As one marketing executive once put it:

The customer is only going to pay you for what he perceives as real value-added. When you look at your overhead, you’ve got to ask yourself if the customer is really willing to pay for that. If the answer is no, you’ve got to figure out how to get rid of it or you’re not going to make money.54

To reduce its costs to achieve value pricing, Procter & Gamble cut overhead according to four simple guidelines: change the work, do more with less, eliminate work, and reduce costs that cannot be passed on to consumers. P&G simplified the distribution chain to make restocking more efficient through continuous product replenishment. The company also scaled back its product portfolio by eliminating 25 percent of its stock-keeping units.

Firms have to be able to develop business models and cost structures to support their pricing plans. Taco Bell reduced operating costs enough to lower prices for many items on the menu to under $1, sparking an industry-wide trend in fast foods. Unfortunately, many other fast food chains found it difficult to lower their overhead costs enough or found that their value menu cannibalized more profitable items.55

Cost reductions certainly cannot sacrifice quality, effectiveness, or efficiency. Toyota and Johnson & Johnson’s Tylenol both experienced brand crises due to product problems, which analysts and even some of the management of the two firms attributed to overly zealous cost reductions. When H&R Block cut costs as it moved into new areas outside tax preparation, customer service suffered and customers began to complain about long wait times and rudeness.56

Product Prices

The final key to a successful value-pricing strategy is to understand exactly how much value consumers perceive in the brand and thus to what extent they will pay a premium over product costs.57 A number of techniques are available to estimate these consumer value perceptions. Perhaps the most straightforward approach is to directly ask consumers their perceptions of price and value in different ways.

The price suggested by estimating perceived value can often be a starting point for marketers in determining actual marketplace prices, adjusting by cost and competitive considerations as necessary. For example, to halt a precipitous slide in market share for its flagship 9-Lives brand, the pet products division of H. J. Heinz took a new tack in its pricing strategy. The company found from research that consumers wanted to be able to buy cat food at the price of “four cans for a dollar,” despite the fact that its cat food cost between 29 and 35 cents per can. As a result, Heinz reshaped its product packaging and redesigned its manufacturing processes to be able to hit the necessary cost, price, and margin targets. Despite lower prices, profits for the brand doubled.

Communicating Value

Combining these three components in the right way to create value is crucial. Just delivering good value, however, is necessary but not sufficient for achieving pricing success—consumers have to actually understand and appreciate the value of the brand. In many cases, that value may be obvious—the product or service benefits are clear and comparisons with competitors are easy. In other cases, however, value may not be obvious, and consumers may too easily default to purchasing lower-priced competitors. Then marketers may need to engage in marketing communications to help consumers better recognize the value. In some cases, the solution may simply require straightforward communications that expand on the value equation for the brand, such as stressing quality for price. In other cases, it may involve “framing” and convincing consumers to think about their brand and product decisions differently.

For example, take a premium-priced brand such as Procter & Gamble’s Pantene. It faces pressure from many competing brands, but especially private-label and store and discount brands that may cost much less. In tough times, even small cost savings may matter to penny-pinching consumers. Assume a bottle of Pantene cost a $1 more than its main competitors but could be used for up to 100 shampoos. In that case, the price difference is really only one cent per shampoo. By framing the purchase decision in terms of cost per shampoo, P&G could then advertise, “Isn’t it worth a penny more to get a better-looking head of hair?”

Price Segmentation

At the same time, different consumers may have different value perceptions and therefore could—and most likely should—receive different prices. Price segmentation sets and adjusts prices for appropriate market segments. Apple has a three-tier pricing scheme for iTunes downloads—a base price of 99 cents, but $1.29 for popular hits and 69 cents for oldies-but-not-so-goodies.58 Starbucks similarly has raised the prices of some of its specialty beverages while charging less for some basic drinks.59

In part because of wide adoption of the Internet, firms are increasingly employing yield management principles or dynamic pricing, such as those adopted by airlines to vary their prices for different market segments according to their different demand and value perceptions. Here are several examples:

-

Allstate Insurance embarked on a yield management pricing program, looking at drivers’ credit history, demographic profile, and other factors to better match automobile policy premiums to customer risk profiles.60

-

To better compete with scalpers and online ticket brokers such as StubHub, concert giant Ticketmaster has begun to implement more efficient variable pricing schemes based on demand that charge higher prices for the most sought-after tickets and lower prices for less-desirable seats for sporting events and concerts.61

-

The San Francisco Giants now uses a software system that allows the team to look at different variables such as current ticket sales, weather forecasts, and pitching matchups to determine whether it should adjust prices—right up until game day. The software allows the team to take the price-tier strategy baseball has traditionally used and make it more dynamic.62

-

New start-up Village Vines offers a demand-management solution to restaurants that allows them to effectively price discriminate by offering deal-prone customers the option of making reservations for 30 percent off the entire bill on select (less desirable) days and times.63

Everyday Low Pricing

Everyday low pricing (EDLP) has received increased attention as a means of determining price discounts and promotions over time. EDLP avoids the sawtooth, whiplash pattern of alternating price increases and decreases or discounts in favor of a more consistent set of “everyday” base prices on products. In many cases, these EDLP prices are based on the value-pricing considerations we’ve noted above.

The P&G Experience

In the early 1990s, Procter & Gamble made a well-publicized conversion to EDLP.64 By reducing list prices on half its brands and eliminating many temporary discounts, P&G reported that it saved $175 million in 1991, or 10 percent of its previous year’s profits. Advocates of EDLP argue that maintaining consistently low prices on major items every day helps build brand loyalty, fend off private-label inroads, and reduce manufacturing and inventory costs.65

The San Francisco Giants have used yield pricing at their AT&T Park home, basing prices for any seat at any game on a number of different factors.

Source: Aurora Photos/Alamy

Even strict adherents of EDLP, however, see the need for some types of price discounts over time. When P&G encountered some difficulties in the late 1990s, it altered its value-pricing strategy in some segments and reinstated selected price promotions. More recently, P&G has adopted a more fluid pricing strategy in reaction to market conditions.66 Although P&G lowered prices in 2010 to try to gain market share in the depths of a severe recession, the company actually raised some prices to offset rising commodity costs in 2011. Management felt confident about the strength of some of the firm’s popular premium-priced brands—such as Fusion ProGlide, Crest 3-D products, and Old Spice body wash—where demand had actually even exceeded supply.

As Chapter 6 will discuss, well -conceived, timely sales promotions can provide important financial incentives to consumers and induce sales. As part of revenue-management systems or yield-management systems, many firms have been using sophisticated models and software to determine the optimal schedule for markdowns and discounts.67

Reasons for Price Stability

Why then do firms seek greater price stability? Manufacturers can be hurt by an overreliance on trade and consumer promotions and the resulting fluctuations in prices for several reasons.

For example, although trade promotions are supposed to result in discounts on products only for a certain length of time and in a certain geographic region, that is not always the case. With forward buying, retailers order more product than they plan to sell during the promotional period so that they can later obtain a bigger margin by selling the remaining goods at the regular price after the promotional period has expired. With diverting, retailers pass along or sell the discounted products to retailers outside the designated selling area.

From the manufacturer’s perspective, these retailer practices created production complications: factories had to run overtime because of excess demand during the promotion period but had slack capacity when the promotion period ended, costing manufacturers millions. On the demand side, many marketers felt that the seesaw of high and low prices on products actually trained consumers to wait until the brand was discounted or on special to buy it, thus eroding its perceived value. Creating a brand association to “discount” or “don’t pay full price” diminished brand equity.

Summary

To build brand equity, marketers must determine strategies for setting prices and adjusting them, if at all, over the short and long run. Increasingly, these decisions will reflect consumer perceptions of value. Value pricing strikes a balance among product design, product costs, and product prices. From a brand equity perspective, consumers must find the price of the brand appropriate and fair given the benefits they feel they receive by the product and its relative advantages with respect to competitive offerings, among other factors. Everyday low pricing is a complementary pricing approach to determine the nature of price discounts and promotions over time that maintains consistently low, value-based prices on major items on a day-to-day basis.

There is always tension between lowering prices on the one hand and increasing consumer perceptions of product quality on the other. Academic researchers Lehmann and Winer believe that although marketers commonly use price reductions to improve perceived value, in reality discounts are often a more expensive way to add value than brand-building marketing activities.68 Their argument is that the lost revenue from a lower margin on each item sold is often much greater than the additional cost of value-added activities, primarily because many of these costs are fixed and spread over all the units sold, as opposed to the per unit reductions that result from lower prices.

Channel Strategy

The manner by which a product is sold or distributed can have a profound impact on the equity and ultimate sales success of a brand. Marketing channels are defined as “sets of interdependent organizations involved in the process of making a product or service available for use or consumption.”69 Channel strategy includes the design and management of intermediaries such as wholesalers, distributors, brokers, and retailers. Let’s look at how channel strategy can contribute to brand equity.70

Channel Design

A number of possible channel types and arrangements exist, broadly classified into direct and indirect channels. Direct channels mean selling through personal contacts from the company to prospective customers by mail, phone, electronic means, in-person visits, and so forth. Indirect channels sell through third-party intermediaries such as agents or broker representatives, wholesalers or distributors, and retailers or dealers.

Increasingly, winning channel strategies will be those that can develop “integrated shopping experiences” that combine physical stores, Internet, phone, and catalogs. For example, consider the wide variety of direct and indirect channels by which Nike sells its shoes, apparel, and equipment products:71

-

Branded Niketown stores: Over 500 Niketown stores, located in prime shopping avenues in metropolitan centers around the globe, offer a complete range of Nike products and serve as showcases for the latest styles. Each store consists of a number of individual shops or pavilions that feature shoes, clothes, and equipment for a different sport (tennis, jogging, biking, or water sports) or different lines within a sport (there might be three basketball shops and two tennis shops). Each shop develops its own concepts with lights, music, temperature, and multimedia displays. Nike is also experimenting with newer, smaller stores that target specific customers and sports (a running-only store in Palo Alto, CA; a soccer-only store in Manchester, England).

-

NikeStore.com: Nike’s e-commerce site allows consumers to place Internet orders for a range of products or to custom-design some products through NIKEiD, which surpassed $100 million in sales in 2010.

-

Outlet stores: Nike’s outlet stores feature discounted Nike merchandise.

-

Retail: Nike products are sold in retail locations such as shoe stores, sporting goods stores, department stores, and clothing stores.

Nike uses a variety of different channels for different purposes. Its Niketown stores have been very useful as a brand-building tool.

Source: AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez

-

Catalog retailers: Nike’s products appear in numerous shoe, sporting goods, and clothing catalogs.

-

Specialty stores: Nike equipment from product lines such as Nike Golf is often sold through specialty stores such as golf pro shops.

Much research has considered the pros and cons of selling through various channels. Although the decision ultimately depends on the relative profitability of the different options, some more specific guidelines have been proposed. For example, one study for industrial products suggests that direct channels may be preferable when product information needs are high, product customization is high, product quality assurance is important, purchase lot size is important, and logistics are important. On the other hand, this study also suggests that indirect channels may be preferable when a broad assortment is essential, availability is critical, and after-sales service is important. Exceptions to these generalities exist, especially depending on the market segments.72

From the viewpoint of consumer shopping and purchase behaviors, we can see channels as blending three key factors: information, entertainment, and experiences.

-

Consumers may learn about a brand and what it does and why it is different or special.

-

Consumers may also be entertained by the means by which the channel permits shopping and purchases.

-

Consumers may be able to participate in and experience channel activities.

It is rare that a manufacturer will use only a single type of channel. More likely, the firm will choose a hybrid channel design with multiple channel types.73 Marketers must manage these channels carefully, as Tupperware found out.

Tupperware

In the 1950s, Tupperware pioneered the plastic food-storage container business and the means by which the containers were sold. With many mothers staying at home and growth in the suburbs exploding, Tupperware parties with a local neighborhood host became a successful avenue for selling. Unfortunately, with more women entering the workforce and heightened competition from brands such as Rubbermaid, Tupperware sales closed out the twentieth century with a 15-year decline. Sales turned around only with some new approaches to selling, including booths at shopping malls and a move to the Internet. The decision to place products in all 1,148 Target stores, however, was a complete disaster. In-store selling was difficult given the very different retail environment. Moreover, because the product was made more widely available, interest in traditional in-home parties plummeted. Frustrated, many salespeople dropped out and fewer new ones were recruited. Although the products were yanked from the stores, the damage was done and profit plunged almost 50 percent. As one key distributor commented, “We just bit off more than we could chew.”74

Tupperware made a serious mistake revising its channel strategy to sell through Target.

Source: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

The risk in designing a hybrid channel system is having too many channels (leading to conflict among channel members or a lack of support), or too few channels (resulting in market opportunities being overlooked). The goal is to maximize channel coverage and effectiveness while minimizing channel cost and conflict.

Because marketers use both direct and indirect channels, let’s consider the brand equity implications of the two major channel design types.

Indirect Channels

Indirect channels can consist of a number of different types of intermediaries, but we will concentrate on retailers. Retailers tend to have the most visible and direct contact with customers and therefore have the greatest opportunity to affect brand equity. As we will outline in greater detail in Chapter 7, consumers may have associations to any one retailer on the basis of product assortment, pricing and credit policy, and quality of service, among other factors. Through the products and brands they stock and the means by which they sell, retailers strive to create their own brand equity by establishing awareness and strong, favorable, and unique associations.

At the same time, retailers can have a profound influence on the equity of the brands they sell, especially in terms of the brand-related services they can support or help create. Moreover, the interplay between a store’s image and the brand images of the products it sells is an important one. Consumers make assumptions such as “this store only sells good-quality, high-value merchandise, so this particular product must also be good quality and high value.”

Push and Pull Strategies

Besides the indirect avenue of image transfer, retailers can directly affect the equity of the brands they sell. Their methods of stocking, displaying, and selling products can enhance or detract from brand equity, suggesting that manufacturers must take an active role in helping retailers add value to their brands. A topic of great interest in recent years in that regard is shopper marketing.

Though defined differently by different people, at its core shopper marketing emphasizes collaboration between manufacturers and retailers on in-store marketing like brand-building displays, sampling promotions, and other in-store activities designed to capitalize on a retailer’s capabilities and its customers. Vlasic is a brand that has ramped up its shopper marketing program.

Vlasic

Although many homes keep a jar of pickles in their refrigerator, too often it ends up in the back of a shelf, where it is forgotten. When summer barbecue season rolls along, pickle consumption increases, although still not as much as market leader Vlasic would like. Company research revealed that about 80 percent of pickles consumed in U.S. homes accompany a hamburger or other sandwich, but only 3 percent of all sandwiches consumed are served with pickles. Compounding the consumption problem is a shopping obstacle. Pickles typically are stocked in the center aisles of stores, where only about 20 percent of shoppers turn on any given trip, compared with the produce or deli aisles on the perimeter of the store, where about 60 percent shop. Vlasic did have one advantage with which to work. Through the years, its iconic brand character—a stork with a Groucho Marx look and personality—had become widely recognizable from all its advertising appearances. For the 2011 summer selling season, Vlasic decided to pull all those factors together to try something different in its marketing. In-store ad cutouts with the stork began to appear in sections of the supermarket away from where pickles were stocked. In the meat section, for example, an ad was placed that included a speech balloon near the stork’s beak proclaiming: “Pro tip: Serve your burgers with a Vlasic pickle. Amateur tip: Don’t.” Similar type ads appeared near the hamburger buns in the bread aisle and all through the cheese aisles. The ads also appeared on shopping carts and on vinyl ads on the supermarket floor. To provide further marketing support outside the store, print ads for the brand stating “Bring On the Bite” appeared in magazines and on Web sites.75

Vlasic’s concerted shopper marketing program paid off nicely in the marketplace.

Source: Pinnacle Foods Group LLC

Such collaborative efforts can spur greater sales of a brand. Yet, at the same time, much conflict has also emerged in recent years between manufacturers and the retailers making up their channels of distribution. Because of greater competition for shelf space among what many retailers feel are increasingly undifferentiated brands, retailers have gained power and are now in a better position to set the terms of trade with manufacturers. Increased power means that retailers can command more frequent and lucrative trade promotions.

One way for manufacturers to regain some of their lost leverage is to create strong brands through some of the brand-building tactics described in this book , for example, by selling innovative and unique products—properly priced and advertised—that consumers demand. In this way, consumers may ask or even pressure retailers to stock and promote manufacturers’ products.

By devoting marketing efforts to the end consumer, a manufacturer is said to employ a pull strategy, since consumers use their buying power and influence on retailers to “pull” the product through the channel. Alternatively, marketers can devote their selling efforts to the channel members themselves, providing direct incentives for them to stock and sell products to the end consumer. This approach is called a push strategy, because the manufacturer is attempting to reach the consumer by “pushing” the product through each step of the distribution chain.

Although certain brands seem to emphasize one strategy more than another (push strategies are usually associated with more selective distribution, and pull strategies with broader, more intensive distribution), the most successful marketers—brands like Apple, Coca-Cola, and Nike—skillfully blend push and pull strategies.

Marketing research |

Gathering information necessary for planning and facilitating interactions with customers |

Communications |

Developing and executing communications about the product and service |

Contact |

Seeking out and interacting with prospective customers |

Matching |

Shaping and fitting the product/service to the customer’s requirements |