11 Designing and Implementing Brand Architecture Strategies

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

-

Define the key components of brand architecture.

-

Outline the guidelines for developing a good brand portfolio.

-

Assemble a basic brand hierarchy for a brand.

-

Describe how a corporate brand is different from a product brand.

-

Explain the rationale behind cause marketing and green marketing.

Honda adopted an alphanumeric-based brand architecture for its Acura brand—including the Acura TL shown here—to better compete in the luxury automobile market.

Source: American Honda Motor Co., Inc.

Preview

Parts II, III, and IV of this book text examined strategies for building and measuring brand equity. Part V takes a broader perspective and considers how to sustain, nurture, and grow brand equity under various situations and circumstances.

The successful launch of new products and services is of paramount importance to firms’ long-term financial prosperity. Firms must maximize brand equity across all the different brands and products and services they offer. Their brand architecture strategy determines which brand elements they apply across all their new and existing products and services and is the means by which they help consumers understand those products and services and organize them in their minds.

Many firms employ complex brand architecture strategies. For example, brand names may consist of multiple brand-name elements (Toyota Camry XLE) and may be applied across a range of products (Toyota cars and trucks). What is the best way to characterize a firm’s brand architecture strategy? What guidelines exist for choosing the right combinations of brand names and other brand elements to best manage brand equity across the entire range of a firm’s products?

We begin by outlining a three-step process to develop an effective brand architecture strategy. We next describe two important strategic tools—brand portfolios and brand hierarchies—which, by defining various relationships among brands and products, help characterize and formulate brand architecture strategies. We then consider corporate branding strategies. After outlining corporate image dimensions, we examine three specific issues in managing a corporate brand: corporate social responsibility, corporate image campaigns, and corporate name changes. Brand Focus 11.0 devotes special attention to the topics of cause marketing and green marketing.

Developing a Brand Architecture Strategy

The firm’s brand architecture strategy helps marketers determine which products and services to introduce, and which brand names, logos, symbols, and so forth to apply to new and existing products. As we describe below, it defines both the brand’s breadth or boundaries and its depth or complexity. Which different products or services should share the same brand name? How many variations of that brand name should we employ? The role of brand architecture is twofold:

-

To clarify brand awareness: Improve consumer understanding and communicate similarity and differences between individual products and services.

-

To improve brand image: Maximize transfer of equity between the brand and individual products and services to improve trial and repeat purchase.

Developing a brand architecture strategy requires three key steps: (1) defining the potential of a brand in terms of its “market footprint,” (2) identifying the product and service extensions that will allow the brand to achieve that potential, and (3) specifying the brand elements and positioning associated with the specific products and services for the brand. Although we introduce all three topics here, this chapter concentrates on insights and guidelines into the first and third. Chapter 12 exclusively focuses on the second topic and how to launch successful brand extensions. The Science of Branding 11-1 describes a useful tool to help depict brand architecture strategies for a firm.

Step 1: Defining Brand Potential

The first step in developing an architecture strategy is to define the brand potential by considering three important characteristics: (1) the brand vision, (2) the brand boundaries, and (3) the brand positioning.

Articulating the Brand Vision

Brand vision is management’s view of the brand’s long-term potential. It is influenced by how well the firm is able to recognize the current and possible future brand equity. Many brands have latent brand equity that is never realized because the firm is unable or unwilling to consider all that the brand could and should become.

On the other hand, many brands have transcended their initial market boundaries to become much more. Waste Management is in the process of transforming itself from a “trash company” to a “one-stop, green, environmental services shop” that does a lot more than just collect and dispose of garbage. Its new tag line, “Think Green,” signals the direction it is taking to find ways to extract value from the waste stream through materials-recovery facilities (MRFs) that enable “single-stream recycling.”1 Google is clearly in the process of being much more than a search engine as it offers more and more services. Another brand that has already transcended its traditional boundaries is Crayola.

Waste Management is transforming itself from a “trash company” to a “one-stop, green, environmental services shop.”

Source: Waste Management

Crayola

Crayola, known for its crayons, first sought to expand its brand meaning by making some fairly direct brand extensions into other drawing and coloring implements, such as markers, pencils, paints, pens, brushes, and chalk. The company further expanded beyond coloring and drawing into arts and crafts, with extensions such as Crayola Chalk, Crayola Clay, Crayola Dough, Crayola Glitter Glue, and Crayola Scissors. These extensions established a new brand meaning for Crayola as “colorful arts and crafts for kids.” Crayola says its brand essence is to find the “what if” in each child:

“We believe in unleashing, nurturing and celebrating the colorful originality in every child. We give kids an invitation that ignites, colors that inspire, and tools that transform original thoughts into visible form. We give colorful wings to the invisible things that grow in the hearts of children. Because we believe that creatively alive kids grow into inspired adults.”

Subsequent category extensions allowed kids to use their imagination to create colorful jewelry, glow-in-the-dark animation, and comic books.2

Without a clear understanding of its current equity, however, it is difficult to understand what the brand could be built on. A good brand vision has a foot in both the present and the future. Brand vision obviously needs to be aspirational, so the brand has room to grow and improve in the future, yet it cannot be unobtainable. The trick is to strike the right balance between what the brand is and what it could become, and to identify the right steps to get it there.

Fundamentally, brand vision relates to the “higher-order purpose” of the brand, based on keen understanding of consumer aspirations and brand truths. It transcends the brand’s physical product category descriptions and boundaries. P&G’s legendary former CMO Jim Stengel maintains that successful brands have clear “ideals”—such as “eliciting joy, enabling connection, inspiring exploration, evoking pride or impacting society”—and a strong purpose of building customer loyalty and driving revenue growth.3 The Science of Branding 11-2 describes one perspective on how firms can maximize a brand’s long-term value according to their vision of its potential.

Defining the Brand Boundaries

Some of the world’s strongest brands, such as GE, Virgin, and Apple, have been stretched across multiple categories. Defining brand boundaries thus means—based on the brand vision and positioning—identifying the products or services the brand should offer, the benefits it should supply, and the needs it should satisfy.

Although many product categories may seem to be good candidates for a brand extension, as we will develop in greater detail in Chapter 12, marketers would be wise to heed the “Spandex Rule” espoused by Scott Bedbury, former VP-Advertising for Nike and VP-Marketing for Starbucks: “Just because you can . . . doesn’t mean you should!” Marketers must evaluate extending their brand carefully and launch new products selectively.

A “broad” brand is one with an abstract positioning that is able to support a higher-order promise relevant in multiple product settings. It often has a transferable point-of-difference, thanks to a widely relevant benefit supported by multiple reasons-to-believe or supporting attributes. For example, Delta Faucet Company has taken its core brand associations of “stylish” and “innovative” and successfully expanded the brand from faucets to a variety of kitchen and bathroom products and accessories.

Nevertheless, all brands have boundaries. It would be very difficult for Delta to introduce a car, tennis racquet, or lawnmower. Japanese carmakers Honda, Nissan, and Toyota chose to introduce their luxury brands in North America under new brand names, Acura, Infiniti, and Lexus, respectively. Even considering its own growth, Nike chose to purchase Cole Haan to sell into the dressier, more formal shoe market. Some brands have struggled to stretch into new markets, as did VW Phaeton.

VW Phaeton

Auto industry insiders were surprised when VW chose to introduce the $85,000 VW Phaeton luxury sedan in 2002. Named after the son of the Greek god Helios, the vehicle racked up more than $1.3 billion in development costs. Although VW also owned Audi, management wanted to make the VW brand more upscale to better compete with BMW and Mercedes. But after Phaeton failed to meet sales goals in the United States—selling only 2,253 cars from 2004 to 2006—the brand was pulled from the market in 2006. After continuing to experience annual losses in the highly competitive U.S. market, VW announced in 2011 that it would relaunch a newly redesigned Phaeton at a later date, with a higher-quality interior, renewed front and rear exterior, and new engine choices. VW sees a strong presence in the U.S. luxury car segment as vital to its goals of tripling its share in the United States and surpassing Toyota worldwide in sales and profitability.4

VW has struggled to successfully extend its brand upward in the U.S. luxury car market with its Phaeton sub-brand.

Source: Laurent Gillieron/EPA/Newscom

To improve market coverage, companies target different segments with multiple brands in a portfolio. They have to be careful to not over-brand, however, or attempt to support too many brands. The trend among many top marketing companies in recent years has been to focus on fewer, stronger brands. Each should be clearly differentiated and appeal to a sizable enough market segment to justify its marketing and production costs.

Crafting the Brand Positioning

Brand positioning puts some specificity into a brand vision. Chapter 2 reviewed brand positioning considerations in detail; the four key ingredients are: (1) competitive frame of reference, (2) points-of-difference, (3) points-of-parity, and (4) brand mantra. The brand mantra in particular can be very useful in establishing product boundaries or brand “guardrails.” It should offer rational and emotional benefits and be sufficiently robust to permit growth, relevant enough to drive consumer and retailer interest, and differentiated enough to sustain longevity.

Step 2: Identifying Brand Extension Opportunities

Determining the brand vision, boundaries, and positioning in Step 1 helps define the brand potential and provides a clear sense of direction for the brand. Step 2 is to identify new products and services to achieve that potential through a well-designed and implemented brand extension strategy.

A brand extension is a new product introduced under an existing brand name. We differentiate between line extensions, new product introductions within existing categories (Tide Total Care laundry detergent), and category extensions, new product introductions outside existing categories (Tide Dry Cleaners retail outlets).

It is important to carefully plan the optimal sequence of brand extensions to achieve brand potential. The key is to understand equity implications of each extension in terms of points-of-parity and points-of-difference. By adhering to the brand promise and growing the brand carefully through “little steps,” marketers can ensure that brands cover a lot of ground.

For example, through a well-planned and well-executed series of new product introductions in the form of category extensions over a 25-year period, Nike evolved from a company selling running, tennis, and basketball shoes to mostly males between the ages of 12 and 29 in North America in the mid-1980s, to a company now selling athletic shoes, clothing, and equipment across a range of sports to men and women of all ages in virtually all countries.

Launching a brand extension is harder than it might seem. Given that the vast majority of new products are extensions and the vast majority of new products fail, the clear implication is that too many brand extensions fail. An increasingly competitive marketplace will be even more unforgiving to poorly positioned and marketed extensions in the years to come. To increase the likelihood of success, marketers must be rigorous and disciplined in their analysis and development of brand extensions. Chapter 12 provides detailed guidelines for successful brand extension strategies.

Step 3: Branding New Products and Services

The final step in developing the brand architecture is to decide on the specific brand elements to use for any particular new product or service associated with the brand. New products and services must be branded in a way to maximize the brand’s overall clarity and understanding to consumers and customers. What names, looks, and other branding elements are to be applied to the new and existing products for any one brand?

One way we can distinguish brand architecture strategies is by looking at whether a firm is employing an umbrella corporate or family brand for all its products, known as a “branded house,” or a collection of individual brands all with different names, known as a “house of brands.”

-

Firms largely employing a branded house strategy include many business-to-business industrial firms, such as Siemens, Oracle, and Goldman Sachs.

-

Firms largely employing a house of brands strategy include consumer product companies, such as Procter & Gamble, Unilever, and ConAgra.

The reality is that most firms adopt a strategy somewhere between these two end points, often employing various types of sub-brands. Sub-brands are an extremely popular form of brand extension in which the new product carries both the parent brand name and a new name (Apple iPad, Ford Fusion, and American Express Blue card).

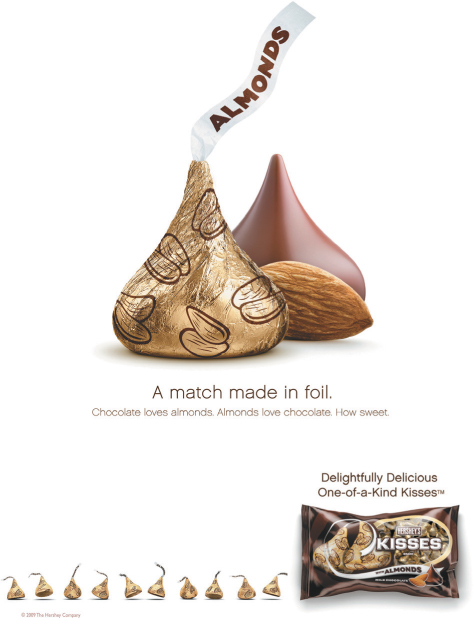

A good sub-branding strategy can tap associations and attitudes about the company or family brand as a whole, while also allowing for the creation of new brand beliefs to position the extension in the new category. For example, Hershey’s Kisses taps into the quality, heritage, and familiarity of the Hershey’s brand but at the same time has a much more playful and fun

An ideal sub-brand, Hershey’s Kisses adds a fun, playful dimension to Hershey’s well-regarded brand image.

Source: ©The Hershey Company

brand image. An iconic brand, Hershey’s Kisses ranked number one in the Harris Interactive EquiTrend brand equity study for 2010.5

Sub-brands play an important brand architecture role by signaling to consumers to expect similarities and differences in the new product. To realize these benefits, however, sub-branding typically requires significant investments and disciplined and consistent marketing to establish the proper brand meanings with consumers. In the absence of such financial commitments, marketers may be well advised to adopt the simplest brand hierarchy possible, such as using a branded house–type approach with the company or a family brand name with product descriptors. Marketers should employ sub-branding only when there is a distinctive, complementary benefit; otherwise, they should just use a product descriptor to designate the new product or service.

Summary

The three steps we outlined provide a careful and well-grounded approach to developing a brand architecture strategy. To successfully execute this process, marketers should use brand portfolio analysis for Step 1 and determining brand potential, and brand hierarchy analysis for Steps 2 and 3 and branding particular products and services. We describe both tools next.

Brand Portfolios

A brand portfolio includes all brands sold by a company in a product category. We judge a brand portfolio by its ability to maximize brand equity: Any one brand in the portfolio should not harm or decrease the equity of the others. Ideally, each brand maximizes equity in combination with all other brands in the portfolio.

Why might a firm have multiple brands in the same product category? The primary reason is market coverage. Although multiple branding was originally pioneered by General Motors, Procter & Gamble is widely recognized as popularizing the practice. P&G became a proponent of multiple brands after introducing its Cheer detergent brand as an alternative to its already successful Tide detergent, resulting in higher combined product category sales.

Firms introduce multiple brands because no one brand is viewed equally favorably by all the different distinct market segments the firm would like to target. Multiple brands allow a firm to pursue different price segments, different channels of distribution, different geographic boundaries, and so forth.6

In designing the optimal brand portfolio, marketers must first define the relevant customer segments. How much overlap exists across segments, and how well can products be cross-sold?7 Branding Brief 11-1 describes how Marriott has introduced different brands and sub-brands to attack different markets.

Other reasons for introducing multiple brands in a category include the following:8

-

To increase shelf presence and retailer dependence in the store

-

To attract consumers seeking variety who may otherwise switch to another brand

-

To increase internal competition within the firm

-

To yield economies of scale in advertising, sales, merchandising, and physical distribution

Marketers generally need to trade off market coverage and these other considerations with costs and profitability. A portfolio is too big if profits can be increased by dropping brands; it is not big enough if profits can be increased by adding brands. Brand lines with poorly differentiated brands are likely to be characterized by much cannibalization and require appropriate pruning.9

The basic principle in designing a brand portfolio is to maximize market coverage so that no potential customers are being ignored, but minimize brand overlap so that brands aren’t competing among themselves to gain the same customer’s approval. Each brand should have a distinct target market and positioning.10

For example, over the last 10 years or so, Procter & Gamble has sought to maximize market coverage and minimize brand overlap by pursuing organic growth from existing core brands rather than introducing a lot of new brands. The company has focused its innovation efforts on its core “billion dollar” brands—those with more than $1 billion in revenue. Numerous successful market-leading brand extensions followed, such as Crest whitening products, Pampers’ training diapers, and Mr. Clean Magic Eraser products.11

Besides these considerations, brands can play a number of specific roles as part of a brand portfolio. Figure 11-4 summarizes some of them, which we review next.

Flankers

Certain brands act as protective flanker or “fighter” brands.12 The purpose of flanker brands typically is to create stronger points-of-parity with competitors’ brands so that more important (and more profitable) flagship brands can retain their desired positioning. In particular, as we noted in Chapter 5, many firms are introducing discount brands as flankers, to better compete with store brands and private labels and to protect their higher-priced brand companions. In Australia, Qantas launched Jetstar airlines as a discount fighter brand to compete with the recently introduced low-priced Virgin Blue airlines—which was meeting with much success—and to protect its flagship premium Qantas brand.13

To attract a particular market segment not currently being covered by other brands of the firm

To serve as a flanker and protect flagship brands

To serve as a cash cow and be milked for profits

To serve as a low-end entry-level product to attract new customers to the brand franchise

To serve as a high-end prestige product to add prestige and credibility to the entire brand portfolio

To increase shelf presence and retailer dependence in the store

To attract consumers seeking variety who may otherwise have switched to another brand

To increase internal competition within the firm

To yield economies of scale in advertising, sales, merchandising, and physical distribution

Figure 11-3 Possible Special Roles of Brands in the Brand Portfolio

In other cases, firms have repositioned existing brands in their portfolio to play that role. The one-time “champagne of bottled beer,” Miller High Life, was relegated to a discount brand in the 1990s to protect premium-priced Miller Genuine Draft and Miller Lite. Similarly, P&G repositioned its one-time top-tier Luvs diaper brand to serve as a price fighter against private labels and store brands to protect the premium Pampers brand.

In designing fighter brands, marketers walk a fine line. Fighters must not be so attractive that they take sales away from their higher-priced comparison brands or referents. At the same time, if they are connected to other brands in the portfolio in any way (say, through a common branding strategy), they must not be designed so cheaply that they reflect poorly on these other brands.

Cash Cows

Some brands may be kept around despite dwindling sales because they still manage to hold on to a sufficient number of customers and maintain their profitability with virtually no marketing support. Marketers can effectively milk these “cash cows” by capitalizing on their reservoir of existing brand equity. For example, while technological advances have moved much of the market to its newer Fusion brand of razors, Gillette still sells its older Trac II, Atra, Sensor, and Mach3 brands. Because withdrawing these may not necessarily switch customers to another Gillette brand, the company may profit more by keeping than discarding them.

Low-End, Entry-Level or High-End, Prestige Brands

Many brands introduce line extensions or brand variants in a certain product category that vary in price and quality. These sub-brands leverage associations from other brands while distinguishing themselves on price and quality. In this case, the end points of the brand line often play a specialized role.

The role of a relatively low-priced brand in the brand portfolio often may be to attract customers to the brand franchise. Retailers like to feature these traffic builders because they often are able to “trade up” customers to a higher-priced brand. For example, Verizon wireless plans allow customers to upgrade their old, sometimes cheaper cell phones to newer versions that are more expensive but still cheaper than retail.

Many of Gillette’s older brands like Trac II, Atra, Sensor, and Mach III are cash cows in that they continue to sell reasonably well without any significant marketing support.

Source: Keri Miksza

BMW introduced certain models into its 3-series automobiles in part as a means of bringing new customers into its brand franchise, with the hope of moving them up to higher-priced models when they traded their cars in. As the 3-series gradually moved up-market, BMW introduced the 1-series in 2004, which was built on the same production line as the 3-series and priced between the 3-series and the MINI.

On the other hand, the role of a relatively high-priced brand in the brand family is often to add prestige and credibility to the entire portfolio. For example, one analyst argued that the real value to Chevrolet of its Corvette high-performance sports car was “its ability to lure curious customers into showrooms and at the same time help improve the image of other Chevrolet cars. It does not mean a hell of a lot for GM profitability, but there is no question that it is a traffic builder.”14 Corvette’s technological image and prestige cast a halo over the entire Chevrolet line.

Summary

Multiple brands can expand coverage, provide protection, extend an image, or fulfill a variety of other roles for the firm. In all brand portfolio decisions, the basic criteria are simple, even though their application can be quite complicated: to minimize overlap and get the most from the portfolio, each brand-name product must have (1) a well-defined role to fulfill for the firm and, thus, (2) a well-defined positioning indicating the benefits or promises it offers consumers. As Chapter 12 reveals, many firms find that due to product proliferation through the years, they now can cut the number of brands and product variants they offer and still profitably satisfy consumers.

Brand Hierarchies

A brand hierarchy is a useful means of graphically portraying a firm’s branding strategy by displaying the number and nature of common and distinctive brand elements across the firm’s products, revealing their explicit ordering. It’s based on the realization that we can brand a product in different ways depending on how many new and existing brand elements we use and how we combine them for any one product.

For example, a Dell Inspiron 17R notebook computer consists of three different brand name elements, “Dell,” “Inspiron,” and “17R.” Some of these may be shared by many different products; others are limited. Dell uses its corporate name to brand many of its products, but Inspiron designates a certain type of computer (portable), and 17R identifies a particular model of Inspiron (designed to maximize gaming performance and entertainment and including a 17-inch screen).

We can construct a hierarchy to represent how (if at all) products are nested with other products because of their common brand elements. Figure 11-5 displays a simple characterization of ESPN’s brand hierarchy. Note that ESPN is owned by Walt Disney Company and functions as a distinct family brand in that company’s brand portfolio. As the figure shows, a brand hierarchy can include multiple levels.

There are different ways to define brand elements and levels of the hierarchy. Perhaps the simplest representation from top to bottom might be:

-

Corporate or company brand (General Motors)

-

Family brand (Buick)

-

Individual brand (Regal)

-

Modifier (designating item or model) (GS)

-

Product description (midsize luxury sport sedan automobile)

Levels of a Brand Hierarchy

Different levels of the hierarchy have different issues, as we review in turn.

Corporate or Company Brand Level

The highest level of the hierarchy technically always consists of one brand—the corporate or company brand. For simplicity, we refer to corporate and company brands interchangeably, recognizing that consumers may not necessarily draw a distinction between the two or know that corporations may subsume multiple companies.

Figure 11-5 ESPN Brand Hierarchy

For legal reasons, the company or corporate brand is almost always present somewhere on the product or package, although the name of a company subsidiary may appear instead of the corporate name. For example, Fortune Brands owns many different companies, such as Jim Beam whiskey, Courvoisier cognac, Master Lock locks, and Moen faucets, but it does not use its corporate name on any of its lines of business.

For some firms like General Electric and Hewlett-Packard, the corporate brand is virtually the only brand. Conglomerate Siemens’s varied electrical engineering and electronics business units are branded with descriptive modifiers, such as Siemens Transportation Systems. In other cases, the company name is virtually invisible and, although technically part of the hierarchy, receives virtually no attention in the marketing program. Black & Decker does not use its name on its high-end DeWalt professional power tools.

As we detail below, we can think of a corporate image as the consumer associations to the company or corporation making the product or providing the service. Corporate image is particularly relevant when the corporate or company brand plays a prominent role in the branding strategy.

Family Brand Level

At the next-lower level, a family brand, also called a range brand or umbrella brand, is used in more than one product category but is not necessarily the name of the company or corporation. For example, ConAgra’s Healthy Choice family brand appears on a wide spectrum of food products, including packaged meats, soups, pasta sauces, breads, popcorn, and ice cream. Some other notable family brands for companies that generate more than $1 billion in sales include Purina and Kit Kat (Nestlé); Mountain Dew, Doritos, and Quaker Foods (PepsiCo); and Oreo, Cadbury, and Maxwell House (Kraft).

Because a family brand may be distinct from the corporate or company brand, company-level associations may be less salient. Most firms typically support only a handful of family brands. If the corporate brand is applied to a range of products, then it functions as a family brand too, and the two levels collapse to one for those products.

Marketers may apply family brands instead of corporate brands for several reasons. As products become more dissimilar, it may be harder for the corporate brand to retain any product meaning or to effectively link the disparate products. Distinct family brands, on the other hand, can evoke a specific set of associations across a group of related products.15

Family brands thus can be an efficient means to link common associations to multiple but distinct products. The cost of introducing a related new product can be lower and the likelihood of acceptance higher when marketers apply an existing family brand to a new product.

On the other hand, if the products linked to the family brand and their supporting marketing programs are not carefully considered and designed, the associations to the family brand may become weaker and less favorable. Moreover, the failure of one product may hurt other products sold under the same brand.

Individual Brand Level

Individual brands are restricted to essentially one product category, although multiple product types may differ on the basis of model, package size, flavor, and so forth. For example, in the “salty snack” product class, Frito-Lay offers Fritos corn chips, Doritos tortilla chips, Lays and Ruffles potato chips, and Rold Gold pretzels. Each brand has a dominant position in its respective product category within the broader salty snack product class.

The main advantage of creating individual brands is that we can customize the brand and all its supporting marketing activity to meet the needs of a specific customer group. Thus, the name, logo, and other brand elements, as well as product design, marketing communication programs, and pricing and distribution strategies, can all focus on a certain target market. Moreover, if the brand runs into difficulty or fails, the risk to other brands and the company itself is minimal. The disadvantages of creating individual brands, however, are the difficulty, complexity, and expense of developing separate marketing programs to build sufficient levels of brand equity.

Modifier Level

Regardless of whether marketers choose corporate, family, or individual brands, they must often further distinguish brands according to the different types of items or models. A modifier is a means to designate a specific item or model type or a particular version or configuration of the product. Land O’Lakes offers “whipped,” “unsalted,” and “regular” versions of its butter. Yoplait yogurt comes as “light,” “custard style,” and “original” flavors.

Adding a modifier often can signal refinements or differences between brands related to factors such as quality levels (Johnnie Walker Red Label, Black Label, and Gold Label Scotch whiskey), attributes (Wrigley’s Spearmint, Doublemint, Juicy Fruit, and Winterfresh flavors of chewing gum), function (Dockers Relaxed Fit, Classic Fit, Straight Fit, Slim Fit, and Extra Slim Fit pants), and so forth.16 Thus, one function of modifiers is to show how one brand variation relates to others in the same brand family.

Modifiers help make products more understandable and relevant to consumers or even to the trade. They can even become strong trademarks if they are able to develop a unique association with the parent brand—only Uncle Ben has “Converted Rice,” and only Orville Redenbacher sells “Gourmet Popping Corn.”17

Product Descriptor

Although not considered a brand element per se, the product descriptor for the branded product may be an important ingredient of branding strategy. The product descriptor helps consumers understand what the product is and does and also helps define the relevant competition in consumers’ minds.

In some cases, it may be hard to describe succinctly what the product is, a new product with unusual functions or even an existing product that has dramatically changed. Public libraries are no longer about checking out books or taking a preschooler to story time. A full-service modern public library serves as an educational, cultural, social, and recreational community center.

In the case of a truly new product, introducing it with a familiar product name may facilitate basic familiarity and comprehension, but perhaps at the expense of a richer understanding of how the new product is different from closely related products that already exist.

Designing a Brand Hierarchy

Given the different possible levels of a brand hierarchy, a firm has a number of branding options available, depending on whether and how it employs each level. Designing the right brand hierarchy is crucial. Branding Brief 11-2 describes the firestorm Netflix encountered when it attempted to make a significant change to its brand hierarchy.

Decide on which products are to be introduced.

Principle of growth: Invest in market penetration or expansion vs. product development according to ROI opportunities.

Principle of survival: Brand extensions must achieve brand equity in their categories.

Principle of synergy: Brand extensions should enhance the equity of the parent brand.

Decide on the number of levels.

Principle of simplicity: Employ as few levels as possible.

Principle of clarity: Logic and relationship of all brand elements employed must be obvious and transparent.

Decide on the levels of awareness and types of associations to be created at each level.

Principle of relevance: Create abstract associations that are relevant across as many individual items as possible.

Principle of differentiation:Differentiate individual items and brands.

Decide on how to link brands from different levels for a product.

Principle of prominence: The relative prominence of brand elements affects perceptions of product distance and the type of image created for new products.

Decide on how to link a brand across products.

Principle of commonality: The more common elements products share, the stronger the linkages.

Figure 11-6 Guidelines for Brand Hierarchy Decisions

Brand elements at each level of the hierarchy may contribute to brand equity through their ability to create awareness as well as foster strong, favorable, and unique brand associations and positive responses. The challenge in setting up a brand hierarchy is to decide:

-

The specific products to be introduced for any one brand.

-

The number of levels of the hierarchy to use.

-

The desired brand awareness and image at each level.

-

The combinations of brand elements from different levels of the hierarchy, if any, to use for any one particular product.

-

The best way to link any one brand element, if at all, to multiple products.

The following discussion reviews these five decisions. Figure 11-6 summarizes guidelines in each of these areas to assist in the design of brand hierarchies.

Specific Products to Introduce

Consistent with discussions in other chapters about what products a firm should introduce for any one brand, we can note three principles here.

The principle of growth maintains that investments in market penetration or expansion versus product development for a brand should be made according to ROI opportunities. In other words, firms must make cost–benefit calcuations for investing resources in selling more of a brand’s existing products to new customers versus launching new products for the brand.

In seeing its traditional networking business slow down, Cisco decided to bet big on new Internet video products. Although video has become more pervasive in almost all media (cell phones, Internet, etc.), the bulky size of files creates transmission challenges. Cisco launched Telepresence technology to permit high-definition videoconferencing for its corporate customers and is infusing its entire product line with greater video capabilities through its medianet architecture.18

The other two principles address the dynamics of brand extension success, as developed in great detail in Chapter 12. The principle of survival states that brand extensions must achieve brand equity in their categories. In other words, “me too” extensions must be avoided. The prin ciple of synergy states that brand extensions should also enhance the equity of the parent brand.

Number of Levels of the Brand Hierarchy

Given product boundaries and an extension strategy in place for a brand, the first decision to make in defining a branding strategy is, broadly, which level or levels of the branding hierarchy to use. Most firms choose to use more than one level, for two main reasons. Each successive branding level allows the firm to communicate additional, specific information about its products. Thus, developing brands at lower levels of the hierarchy allows the firm flexibility in communicating the uniqueness of its products. At the same time, developing brands at higher levels of the hierarchy is obviously an economical means of communicating common or shared information and providing synergy across the company’s operations, both internally and externally.

As we noted above, the practice of combining an existing brand with a new brand is called sub-branding, because the subordinate brand is a means of modifying the superordinate brand. A sub-brand, or hybrid branding, strategy can also allow for the creation of specific brand beliefs. Pepsi is working hard to create a number of sub-brands for its Gatorade brand.

Gatorade

First created by researchers at the University of Florida in the mid-1960s—whose nickname for its sports teams the “Gators” gave the product its name—Gatorade was a carbohydrate-electrolyte beverage designed to replace what the school’s athletes would lose from sweating in the intense Gainsville heat. Pioneering the sports drink market, Gatorade became an on-court and off-court staple for athletes everywhere. PepsiCo bought Quaker Oats and the brand in 2000, but after a decade of ownership, sales began to slump. A slew of new water and energy drink competitors helped erode Gatorade’s sales. The “What is G?” ad campaign failed to reignite sales in 2009. That year, Pepsi marketers decided to launch the innovative new “G series” to reconnect with competitive athletes and to ensure that Gatorade was not seen as “the sports drink of my father.” The G series was designed to “fuel the body before, during, and after practice, training and competition.” It consisted of three product groupings:

-

Prime 01, pregame fuel in the form of four-ounce beverage pouches packed with carbohydrates, sodium, and potassium to be consumed before athletic activity.

-

Perform 02, the traditional Thirst Quencher and G2 beverage lines used to hydrate and refresh during periods of heavy exertion, exercise, or competition.

-

Recover 03, a protein-packed beverage to aid hydration and muscle recovery after exercise.

Other versions of G Series were also launched. G Series Pro was initially available only for professional athletes but was later broadened to target the more serious amateur; G Series Natural contained natural ingredients like sea salt, fruit flavors, and natural sweetners. G Series Fit was a healthier and low-calorie version of the product line to be used before, during, and after personal workouts.19

Gatorades’s dramatic repositioning included a completely new G Series brand architecture.

Source: Jarrod Weaton/Weaton Digital, Inc.

Sub-branding thus creates a stronger connection to the company or family brand and all the associations that come along with that. At the same time, developing sub-brands also allows for the creation of brand-specific beliefs. This more detailed information can help customers better understand how products vary and which particular product may be the right one for them.

Sub-brands also help organize selling efforts so that salespeople and retailers have a clear picture of how the product line is organized and how best to sell it. For example, one of the main advantages to Nike of continually creating sub-brands in its basketball line with Air Max Lebron, Air Zoom Hyperdunk, and Hyperfuse, as well as the very popular Jordan line, is to generate retail interest and enthusiasm. Ninety-two of the top-100-selling basketball shoes in 2010 were sold by Nike.20

Marketers can employ a host of brand elements as part of a sub-brand, including name, product form, shape, graphics, color, and version. By skillfully combining new and existing brand elements, they can effectively signal the intended similarity or fit of a new extension with its parent brand.

The principle of simplicity is based on the need to provide the right amount of branding information to consumers—no more and no less. The desired number of levels of the brand hierarchy depends on the complexity of the product line or product mix, and thus on the combination of shared and separate brand associations the company would like to link to any one product.

With relatively simple low-involvement products—such as light bulbs, batteries, and chewing gum—the branding strategy often consists of an individual or perhaps a family brand combined with modifiers that describe differences in product features. For example, GE has three main brands of general-purpose light bulbs (Edison, Reveal, and Energy Smart) combined with designations for basic functionality (Standard, Reader, and three-way), aesthetics (soft white and daylight), and performance (40, 60, and 100 watts).

A complex set of products—such as cars, computers, or other durable goods—requires more levels of the hierarchy. Thus, Sony has family brand names such as Cyber-Shot for its cameras, Bravia for TVs, and Handycams for its camcorders.21 A company with a strong corporate brand selling a relatively narrow set of products, such as luxury automobiles, can more easily use nondescriptive alphanumeric product names because consumers strongly identify with the parent brand, as Acura found out.

Acura

Honda grew from humble origins as a motorcycle manufacturer to become a top automobile import competitor in the United States. Recognizing that future sales growth would come from more upscale customers, it set out in the early 1980s to compete with European luxury cars. Since Honda’s image of dependable, functional, and economical cars did not have the cachet to appeal to this segment, the company created the new Acura division. After meeting initial success, however sales began to drop. Research revealed part of the problem: Acura’s Legend, Integra, and Vigor sub-brand names did not communicate luxury and order in the product line as well as the alphanumeric branding scheme of competitors BMW, Mercedes, Lexus, and Infiniti. Honda decided that the strength of the brand should lie in the Acura name. Thus, despite the fact that it had spent nearly $600 million on advertising Acura sub-brands over the previous eight years to build their equity, the firm announced a new alphanumeric branding scheme in the winter of 1995: the 2.5 TL and 3.2 TL (for Touring Luxury) sedan series, the 3.5 RL, the 2.2 CL, and 3.0 CL, and the RSX series. Acura spokesperson Mike Spencer said, “It used to be that people said they owned or drove a Legend.... Now they say they drive an Acura, and that’s what we wanted.” Introducing new models with new names paid off and sales subsequently rose. Although Acura solved its branding problems, a perceived lack of styling has plagued the brand, and in recent years the company has struggled to keep up with its luxury compatriots.22

It’s difficult to brand a product with more than three levels of brand names without overwhelming or confusing consumers. A better approach might be to introduce multiple brands at the same level (multiple family brands) and expand the depth of the branding strategy.

Desired Awareness and Image at Each Hierarchy Level

How much awareness and what types of associations should marketers create for brand elements at each level? Achieving the desired level of awareness and strength, favorability, and uniqueness of brand associations may take some time and call for a considerable change in consumer perceptions. Assuming marketers use some type of sub-branding strategy for two or more brand levels, two general principles—relevance and differentiation—should guide them at each level of the brand knowledge creation process.

The principle of relevance is based on the advantages of efficiency and economy. Marketers should create associations that are relevant to as many brands nested at the level below as possible, especially at the corporate or family brand level. The greater the value of an association in the firm’s marketing, the more efficient and economical it is to consolidate this meaning into one brand linked to all these products.23 For example, Nike’s slogan (“Just Do It”) reinforces a key point-of-difference for the brand—performance—that is relevant to virtually every product it sells.

The more abstract the association, the more likely it is to be relevant in different product settings. Thus, benefit associations are likely to be extremely advantageous because they can cut across many product categories. For brands with strong product category and attribute associations, however, it can be difficult to create a brand image robust enough to extend into new categories.

For example, Blockbuster struggled to expand its meaning from “a place to rent videos” to “your neighborhood entertainment center” in hopes of creating a broader brand umbrella with greater relevance to more products. It eventually declared bankruptcy before being acquired via auction by satellite television provider Dish Network in April 2011.24

The principle of differentiation is based on the disadvantages of redundancy. Marketers should distinguish brands at the same level as much as possible. If they cannot easily distinguish two brands, it may be difficult for retailers or other channel members to justify supporting both, and for consumers to choose between them.

Although new products and brand extensions are critical to keeping a brand innovative and relevant, marketers must introduce them thoughtfully and selectively. Without restraint, brand variations can easily get out of control.25

A grocery store can stock as many as 40,000 items, which raises the question: Do consumers really need nine kinds of Kleenex tissues, Eggo waffles in 16 flavors, and 72 varieties of Pantene shampoo, all of which have been available at one point in time? To better control its inventory and avoid brand proliferation, Colgate-Palmolive began to discontinue one item for each product it introduces.

Although the principle of differentiation is especially important at the individual brand or modifier levels, it’s also valid at the family brand level. For example, one of the criticisms of marketing at General Motors was that the company had failed to adequately distinguish its family brands of automobiles, perhaps ultimately leading to the demise of the Oldsmobile, Pontiac, and Saturn brands.

The principle of differentiation also implies that not all products should receive the same emphasis at any level of the hierarchy. A key issue in designing a brand hierarchy is thus choosing the relative emphasis to place on the different products in it. If a corporate or family brand is associated with multiple products, which product should be the core or flagship product? What product should represent “the brand” to consumers?

A flagship product is one that best represents or embodies the brand to consumers. It is often the first product by which the brand gained fame, a widely accepted best seller, or a highly admired or award-winning product. For example, although other products are associated with their brands, flagship products might be soap for Ivory, credit cards for American Express, and cake mix for Betty Crocker.26

Flagship products play a key role in the brand portfolio in that marketing them can have short-term benefits (increased sales), as well as long-term benefits (improved brand equity). Chrysler put a lot of marketing effort behind its 300 models when they were hot sellers even though they made up only 22 percent of the brand’s total sales, because the 300 also appeared to provide a halo over the rest of the Chrysler line. At a time when General Motors sales were declining by 4 percent, Chrysler’s sales shot up 10 percent.27

Combining Brand Elements from Different Levels

If we combine multiple brand elements from different levels of the brand hierarchy, we must decide how much emphasis to give each. For example, if we adopt a sub-brand strategy, how much prominence should we give individual brands at the expense of the corporate or family brand?

Principle of Prominence

The prominence of a brand element is its relative visibility compared with other brand elements. Prominence depends on several factors, such as order, size, and appearance, as well as semantic associations. A name is generally more prominent when it appears first, is larger, and looks more distinctive. Assume PepsiCo has adopted a sub-branding strategy to introduce a new vitamin-fortified cola, combining its corporate family brand name with a new individual brand name, say, “Vitacola.” We could make the Pepsi name more prominent by placing it first and making it bigger: PEPSI Vitacola. Or we could make the individual brand more prominent by placing it first and making it bigger: Vitacola by pepsi.

The principle of prominence states that the relative prominence of the brand elements determines which become the primary one(s) and which the secondary one(s). Primary brand elements should convey the main product positioning and points-of-difference. Secondary brand elements convey a more restricted set of supporting associations such as points-of-parity or perhaps an additional point-of-difference. A secondary brand element may also facilitate awareness.

For example, with the Droid by Motorola series of smartphones, the primary brand element is the Droid name, which connotes its use of Google’s Android operating system. The Motorola name, on the other hand, is a secondary brand element that ideally conveys credibility, quality, and professionalism. According to the principle of prominence, the more prominent a brand element, the more emphasis consumers will give it in forming their brand opinions. The relative prominence of the individual and the corporate brands will therefore affect perceptions of product distance and the type of image created for a new product.

Consumers are very literal. If the corporate or family brand is made more prominent, then its associations are more likely to dominate. If the individual brand is made more prominent, on the other hand, then it should be easier to create a more distinctive brand image. “Marriott’s Courtyard” would be seen as much more of a Marriott hotel than “Courtyard by Marriott” by virtue of having the corporate name first. In “Courtyard by Marriott,” the position of the corporate or family brand is signaling to consumers that the new product is not as closely related to its other products that share that name. As a result, consumers should be less likely to transfer corporate or family brand associations. At the same time, because of the greater perceived distance, the success or failure of the new product should be less likely to affect the image of the corporate

Branding for the Droid by Motorola emphasizes Google’s Android operating system more than it does the Motorola corporate name.

Source: AP Photo/David Duprey

or family brand. With a more prominent corporate or family brand, however, feedback effects are probably more likely to be evident.

In some cases, the brand elements may not be explicitly linked at all. In a brand endorse ment strategy, a brand element—often the corporate brand name or logo—appears on the package, signage, or product appearance in some way but is not directly included as part of the brand name. The brand endorsement strategy presumably establishes the maximum distance between the corporate or family brand and the individual brands, suggesting that it would yield the smallest transfer of brand associations to the new product but, at the same time, minimize the likelihood of any negative feedback effects.

For example, General Mills places its “Big G” logo on its cereal packages but retains distinct brand names such as Cheerios, Wheaties, and Lucky Charms. Kellogg, on the other hand, adopts a sub-brand strategy that combines the corporate name with individual cereal brands, for instance Kellogg’s Corn Flakes and Kellogg’s Special K. Through its sub-branding strategy and marketing activities, Kellogg should be more effective than General Mills in connecting its corporate name to its products and, as a result, in creating favorable associations to its corporate name.

Branding Strategy Screen

Marketers can use the branding strategy screen displayed in Figure 11-7 to “dial up” or “dial down” different brand elements. If a potential new product or service is strongly related to the parent brand such that there is a high likelihood of parent brand equity carryover, and if there is little equity risk, a product descriptor or parent-brand-first sub-brand may make sense.28

On the other hand, if a potential new product or service is more removed from the parent brand such that there is a lower likelihood of parent brand equity carryover or if there is higher equity risk, then a parent-brand-second sub-brand or even a new brand may be more appropriate. In these latter cases, the parent brand may just be used as an endorser.

These pros and cons help determine whether a “branded house” or “house of brands” is the more appropriate strategy. What consumers know about and want from the brand, and how they will actually use it, is also important. Although offering multiple sub-brands as part of a detailed brand family may seem to provide more descriptive details, it can easily backfire if taken too far.

For example, when one-time technology hotshot Silicon Graphics named its new 3-D work station “Indigo2 Solid Impact,” customers chose to simplify the name by calling it simply “Solid.” Creating equity for a low-level brand modifier (Solid) would certainly not be called good branding practice. Brand equity ideally resides at the highest level of the branding hierarchy possible, where it can benefit more products and services.

Linking Brand Elements to Multiple Products

So far, we’ve highlighted how to apply different brand elements to a particular product—the “vertical” aspects of the brand hierarchy. Next, we consider how to link any one brand element to multiple products—the “horizontal” aspects. The principle of commonality states that the more common brand elements products share, the stronger the linkages between them.

Figure 11-7 Branding Strategy Screen

The simplest way to link products is to use the brand element “as is” across them. Adapting the brand, or some part of it, offers additional possibilities for making the connection.

-

Hewlett-Packard capitalized on its highly successful LaserJet computer printers to introduce a number of new products using the “Jet” suffix, for example, the DeskJet, PaintJet, ThinkJet, and OfficeJet printers.

-

McDonald’s has used its “Mc” prefix to introduce a number of products, such as Chicken McNuggets, Egg McMuffin, and the McRib sandwich.

-

Donna Karan’s DKNY brand, Calvin Klein’s CK brand, and Ralph Lauren’s Double RL brand rely on initials.

We can also create a relationship between a brand and multiple products with common symbols. For example, corporate brands like Nabisco often place their corporate logo more prominently on their products than their name, creating a strong brand endorsement strategy.

Finally, it’s often a good idea to logically order brands in a product line, to communicate how they are related and to simplify consumer decision making. We can communicate the order though colors (American Express offers Red, Blue, Green, Gold, Platinum, and “Black” or Centurion cards), numbers (BMW offers its 3-, 5-, and 7-series cars), or other means. This strategy is especially important in developing brand migration pathways for customers to switch among the brands offered by the company. The relative position of a brand within a brand line may also affect consumer perceptions and preferences.29

Corporate Branding

Given its fundamental importance in brand architecture, we will go into greater detail on corporate branding. A corporate brand is distinct from a product brand in that it can encompass a much wider range of associations. As detailed below, a corporate brand name may be more likely to evoke associations of common products and their shared attributes or benefits, people and relationships, programs and values, and corporate credibility.

These associations can have an important effect on the brand equity and market performance of individual products. For example, one research study revealed that consumers with a more favorable corporate image of DuPont were more likely to respond favorably to the claims made in an ad for Stainmaster carpet and therefore actually buy the product.30

Building and managing a strong corporate brand, however, can necessitate that the firm keep a high public profile, especially to influence and shape some of the more abstract types of associations. The CEO or managing director, if associated with a corporate brand, must also be willing to maintain a more public profile to help communicate news and information, as well as perhaps provide a symbol of current marketing activities. At the same time, a firm must also be willing to subject itself to more scrutiny and be extremely transparent in its values, activities, and programs. Corporate brands thus have to be comfortable with a high level of openness.

A corporate brand offers a host of potential marketing advantages, but only if corporate brand equity is carefully built and nurtured—a challenging task. Many marketing winners in the coming years will therefore be those firms that properly build and manage corporate brand equity. Branding Brief 11-3 describes a closely related concept—corporate reputation—and how we can look at it from the perspective of consumers and other firms.31

Corporate brand equity is the differential response by consumers, customers, employees, other firms, or any relevant constituency to the words, actions, communications, products, or services provided by an identified corporate brand entity. In other words, positive corporate brand equity occurs when a relevant constituency responds more favorably to a corporate ad campaign, a corporate-branded product or service, a corporate-issued PR release, and so on than if the same offering were attributed to an unknown or fictitious company.

A corporate brand can be a powerful means for firms to express themselves in a way that isn’t tied to their specific products or services. The Science of Branding 11-3 describes one approach to defining corporate brand personality.

Corporate Image Dimensions

A corporate image will depend on a number of factors, such as the products a company makes, the actions it takes, and the manner in which it communicates to consumers. This section highlights some of the different types of associations that are likely to be linked to a corporate brand and that can affect brand equity (see Figure 11-9).32

Common Product Attributes, Benefits, or Attitudes

Like individual brands, a corporate or company brand may evoke in consumers a strong association to a product attribute (Hershey with “chocolate”), type of user (BMW with “yuppies”), usage situation (Club Med with “fun times”), or overall judgment (Sony with “quality”).

Common Product Attributes, Benefits, or Attitudes

Quality

Innovativeness

People and Relationships

Customer orientation

Values and Programs

Concern with environment

Social responsibility

Corporate Credibility

Expertise

Trustworthiness

Likability

Figure 11-9 Some Important Corporate Image Associations

If a corporate brand is linked to products across diverse categories, then some of its strongest associations are likely to be those intangible attributes, abstract benefits, or attitudes that span each of the different product categories. For example, companies may be associated with products or services that solve particular problems (Black & Decker), bring excitement and fun to certain activities (Nintendo), are built with the highest quality standards (Motorola), contain advanced or innovative features (Rubbermaid), or represent market leadership (Hertz).

Two specific product-related corporate image associations—high quality and innovation—deserve special attention.

A high-quality corporate image association creates consumer perceptions that a company makes products of the highest quality. A number of different organizations like J.D. Power, Consumer Reports, and various trade publications for automobiles rate products. The Malcolm Baldrige award is one of many that distinguishes companies on the basis of quality. Quality is one of the most important, if not the most important, decision factors for consumers.

An innovative corporate image association creates consumer perceptions of a company as developing new and unique marketing programs, especially with respect to product introductions or improvements. Keller and Aaker experimentally showed how different corporate image strategies—being innovative, environmentally concerned, or involved in the community—could affect corporate credibility and strategically benefit the firm by increasing the acceptance of brand extensions.33 Interestingly, consumers saw a company with an innovative corporate image as not only expert but also trustworthy and likable. Being innovative is seen in part as being modern and up-to-date, investing in research and development, employing the most advanced manufacturing capabilities, and introducing the newest product features.

An image priority for many Japanese companies—from consumer product companies such as Kao to more technically oriented companies such as Canon—is to be perceived as innovative.34 Perceived innovativeness is also a key competitive weapon and priority for firms in other countries. Michelin (“A Better Way Forward”) describes how its commitment to the environment, security, value, and driving pleasure has been spurring innovation. Branding Brief 11-4 describes how 3M has developed an innovative culture and image.

People and Relationships

Corporate image associations may reflect characteristics of the employees of the company. Although focusing on employees is a natural positioning strategy for service firms like Southwest Airlines, Avis car rental, and Ritz-Carlton hotels as well as retailers like Walmart, manufacturing firms like DuPont and others have also used it in the past. Their rationale is that the traits that employees exhibit will directly or indirectly influence consumers about the products the firm makes or the services it provides.

Consumers may themselves form more abstract impressions of a firm’s employees, especially in a services setting. One major public utility company was described by customers as “male, 35–40 years old, middle class, married with children, wearing a flannel shirt and khaki pants, who would be reliable, competent, professional, intelligent, honest, ethical, and business-oriented.” On the downside, these same customers also described the utility as “distant, impersonal, and self-focused,” suggesting an important area for improvement in its corporate brand image.

Retail stores also derive brand equity from their employees. For example, from its origins as a small shoe store, Seattle-based Nordstrom has become one of the nation’s leading fashion specialty retailers through a commitment to quality, value, selection, and, especially, service. Legendary for its “personalized touch” and willingness to go to extraordinary lengths to satisfy its customers, Nordstrom creates brand equity largely through the efforts of its salespeople and the relationships they develop with customers.

Thus, a customer-focused corporate image association creates consumer perceptions of a company as responsive to and caring about its customers. Consumers believe their voice will be

heard and that the company has their best interests in mind. Often this philosophy is reflected throughout the marketing program and communicated through advertising.

Values and Programs

Corporate image associations may reflect company values and programs that do not always directly relate to the products. Firms can run corporate-image ad campaigns to describe to consumers, employees, and others their philosophy and actions with respect to organizational, social, political, or economic issues.

For example, many recent corporate advertising campaigns have focused on environmental issues and social responsibility. A socially responsible corporate image association portrays the company as contributing to community programs, supporting artistic and social activities, and generally attempting to improve the welfare of society as a whole. An environmentally concerned corporate image association projects a company whose products protect or improve the environment and make more effective use of scarce natural resources. We consider corporate responsibility in more detail below, and Brand Focus 11.0 looks at the broader issue of cause marketing, in which British Airways has been a pioneer.

British Airways

An innovative cause marketer, British Airways has successfully introduced several noteworthy cause programs. It first partnered with UNICEF in 1994 for the cleverly titled Change for Good campaign, based on a very simple idea: foreign coins are particularly difficult to exchange at banks and currency exchanges. So passengers were asked to place any surplus coins—or bills, for that matter—in envelopes provided by British Airways, which donated them directly to UNICEF. British Airways advertised the program on the backs of seat cards, during an in-flight video, and with in-flight announcements with such success that fellow international carriers in the Oneworld Alliance began to participate. In June 2010, the program was replaced with the Flying Start program. This new program was a partnership with Comic Relief UK, a successful charity started by comedians whose aim is to “bring about positive and lasting change in the lives of poor and disadvantaged people.” To publicize the new program, the airlines teamed up with Guinness World Records for the “Highest Stand-Up Comedy Gig in the World.” Three comedians entertained 75 lucky passengers for a two-and-a-half-hour champagne flight. Flying Start was structured like Change for Good—donations were collected in-flight as well as online and at Travelex currency exchange locations in UK airports—but had a stronger local angle. The program raised almost $3 million in its first year, with a goal of raising $20 million by 2013 to “improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of children living in the UK and in some of the poorest countries across the world.”35

Corporate Credibility

A particularly important set of abstract brand associations is corporate credibility. As defined in Chapter 2, corporate credibility measures the extent to which consumers believe a firm can design and deliver products and services that satisfy their needs and wants. It is the reputation the firm has achieved in the marketplace. Corporate credibility—as well as success and leadership—depend on three factors:

-

Corporate expertise: The extent to which consumers see the company as able to competently make and sell its products or conduct its services

-

Corporate trustworthiness: The extent to which consumers believe the company is motivated to be honest, dependable, and sensitive to customer needs

-

Corporate likability: The extent to which consumers see the company as likable, attractive, prestigious, dynamic, and so forth

While consumers who perceive the brand as credible are more likely to consider and choose it, a strong and credible reputation can offer additional benefits.36 L.L. Bean is a company with much corporate credibility.

L.L. Bean

A brand seen as highly credible, outdoors-product retailer L.L. Bean attempts to earn its customers’ trust every step of the way—by providing prepurchase advice, secure transactions, best-in-class delivery, and easy returns and exchanges. Founded in 1912, L.L. Bean backs its efforts with a 100-percent satisfaction guarantee as well as its Golden Rule: “Sell good merchandise at a reasonable profit, treat your customers like human beings and they will always come back for more.” Now a billion-dollar brand celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2012, the company retains its original image of being passionate about the outdoors and believing profoundly in honesty, product quality, and customer service.37

L.L. Bean’s popular roving Bootmobile was a clever way to create awareness and engagement around its 100th anniversary.

Source: AP Photo/L.L. Bean, Lincoln Benedict

A highly credible company may be treated more favorably by other external constituencies, such as government or legal officials. It also may be able to attract better-qualified employees and motivate existing employees to be more productive and loyal. As one Shell Oil employee remarked as part of some internal corporate identity research, “If you’re really proud of where you work, I think you put a little more thought into what you did to help get them there.”

A strong corporate reputation can help a firm survive a brand crisis and avert public outrage that could otherwise depress sales or block expansion plans. As Harvard’s Stephen Greyser notes, “Corporate reputation . . . can serve as a capital account of favorable attitudes to help buffer corporate trouble.”

Summary

Many intangible brand associations can transcend the physical characteristics of products, providing valuable sources of brand equity and serving as critical points-of-parity or points-of-difference.38 Companies have a number of means—indirect or direct—of creating these associations. But they must “talk the talk” and “walk the walk” by communicating to consumers and backing up claims with concrete programs consumers can easily understand or even experience.

Managing the Corporate Brand

A number of specific issues arise in managing a corporate brand. Here we consider three: corporate social responsibility, corporate image campaigns, and corporate name changes.

Corporate Social Responsibility

Some marketing experts believe consumers are increasingly using their perceptions of a firm’s role in society in their purchase decisions. For example, consumers want to know how a firm treats its employees, shareholders, local neighbors, and other stakeholder or constituents.39 As the head of a large ad agency put it: “The only sustainable competitive advantage any business has is its reputation.”40

Consistent with this reasoning, 91 percent of respondents in a large global survey of financial analysts and others in the investment community agreed that a company that fails to look after its reputation will endure financial difficulties. Moreover, 96 percent said the CEO’s reputation was fairly, very, or extremely important in influencing their ratings.41

The realization that consumers and others may be interested in issues beyond product characteristics and associations has prompted much marketing activity to establish the proper corporate image.42 Some firms are putting corporate social responsibility at the very core of their existence.43 Ben & Jerry’s has created a strong association as a “do-gooder” by using Fair Trade ingredients and donating 7.5 percent of its pretax profits to various causes. Its annual Social and Environmental Assessment Report details the company’s main social mission goals and spells out how it is attempting to achieve them.

TOMS Shoes used cause marketing to launch its brand.

Toms Shoes

When entrepreneur and former reality-show contestant Blake Mycoskie visited Argentina in 2006, he saw masses of children who suffered health risks and interrupted schooling due to a simple lack of shoes. Once home, Mycoskie started TOMS Shoes, whose name conveys “Shoes for a Better Tomorrow” and whose One for One program delivers a free pair of shoes to a needy child for each pair sold. The shoes themselves are based on the classic alpargata style found in Argentina. They’re sold online and through top retailers such as Whole Foods, Nordstrom, and Neiman Marcus. TOMS’s donated shoes—black, unisex canvas slip-ons with a sturdy sole—can now be found on the feet of more than 2 million kids in developing countries such as Argentina and Ethiopia. TOMS has a strong social media presence with almost a million Facebook friends. In 2011, Mycoskie launched TOMS Eyewear, using a similar One for One model in which for every pair of glasses sold, a child in need will receive either medical care, prescription glasses, or sight-saving surgery.44

Founder Blake Mycoskie put social responsibility at the heart of his TOMS Shoes business.

Source: AP Images/PRNewsFoto/TOMS Shoes

Brand Focus 11.0 outlines the advantages of cause marketing, the obstacles they face, and how to successfully design a successful campaign, with particular emphasis on green marketing.

Corporate Image Campaigns

Corporate image campaigns are designed to create associations to the corporate brand as a whole; consequently, they tend to ignore or downplay individual products or sub-brands.45 As we would expect, some of the biggest spenders on these kinds of campaigns are well-known firms that use their company or corporate name prominently in their branding strategies, such as GE, Toyota, British Telecom, IBM, Novartis, and Deutsche Bank.

Corporate image campaigns have been criticized as an ego-stroking waste of time, and they can be easy for consumers to ignore. However, a strong campaign can provide invaluable marketing and financial benefits by allowing the firm to express itself and embellish the meaning of its corporate brand and associations for its individual products, as Philips did.

Philips

To reposition itself as a more consumer-friendly brand, Philips Consumer Electronics launched a global corporate advertising campaign in 2004 that ran for a number of years. Centered on the company’s new tagline, “Sense and Simplicity,” which replaced the nine-year-old “Let’s Make Things Better,” the ads showcased innovative Philips products like the Flat TV with Ambilight, the HDRW720 DVD recorder with built-in hard disk, and the Sonicare Elite toothbrush fitting in effortlessly with users’ sophisticated lifestyles. Philips president and CEO Gerard Kleisterlee described the repositioning campaign by saying, “Our route to innovation isn’t about complexity—it’s about simplicity, which we believe will be the new cool.”46

To maximize the probability of success, however, marketers must clearly define the objectives of a corporate image campaign and carefully measure results against them.47 A number of different objectives are possible in a corporate brand campaign:48

-

Build awareness of the company and the nature of its business.

-

Create favorable attitudes and perceptions of company credibility.

-

Link beliefs that can be leveraged by product-specific marketing.

-

Make a favorable impression on the financial community.

-

Motivate present employees and attract better recruits.

-

Influence public opinion on issues.

In terms of building customer-based brand equity, the first three objectives are particularly critical. A corporate image campaign can enhance awareness and create a more positive image of the corporate brand that will influence consumer evaluations and increase the equity associated with individual products and any related sub-brands. In certain cases, however, the latter three objectives can take on greater importance.49

A corporate image campaign may be useful when mergers or acquisitions transform the company. Consolidation in the financial services industry has caused firms like Zurich and UBS to develop and implement strong corporate branding strategies.

UBS