6 Integrating Marketing Communications to Build Brand Equity

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

-

Describe some of the changes in the new media environment.

-

Outline the major marketing communication options.

-

Describe some of the key tactical issues in evaluating different communication options.

-

Identify the choice criteria in developing an integrated marketing communication program.

-

Explain the rationale for mixing and matching communication options.

Ford launched its new Fiesta model in the United States with a combination of events, traditional media, and a heavy dose of social media.

Source: Ford Motor Company

Preview

The preceding chapter described how various marketing activities and product, price, and distribution strategies can contribute to brand equity. This chapter considers the final and perhaps most flexible element of marketing programs. Marketing communications are the means by which firms attempt to inform, persuade, and remind consumers—directly or indirectly—about the brands they sell. In a sense, marketing communications represent the voice of the brand and are a means by which the brand can establish a dialogue and build relationships with consumers. Although advertising is often a central element of a marketing communications program, it is usually not the only element—or even the most important one—for building brand equity. Figure 6-1 displays some of the common marketing communication options for the consumer market.

Designing marketing communication programs is a complex task. We begin by describing the rapidly changing media landscape and the new realities in marketing communications. To provide necessary background, we next evaluate how the major communication options contribute to brand equity and some of their main costs and benefits. We conclude by considering how to mix and match communication options—that is, how to employ a range of communication options in a coordinated or integrated fashion—to build brand equity. We consider some of what we have learned about advertising in Brand Focus 6.0. For the sake of brevity, we will not consider specific marketing communication issues such as media scheduling, budget estimation techniques, and research approaches or the topic of personal selling.1

Media advertising

TV

Radio

Newspaper

Magazines

Direct response advertising

Mail

Telephone

Broadcast media

Print media

Computer-related

Media-related

Place advertising

Billboards and posters

Movies, airlines, and lounges

Product placement

Point of purchase

Point-of-purchase advertising

Shelf talkers

Aisle markers

Shopping cart ads

In-store radio or TV

Trade promotions

Trade deals and buying allowances

Point-of-purchase display allowances

Push money

Contests and dealer incentives

Training programs

Trade shows

Cooperative advertising

Consumer promotions

Samples

Coupons

Premiums

Refunds and rebates

Contests and sweepstakes

Bonus packs

Price-offs

Interactive

Web sites

E-mails

Banner ads

Rich media ads

Search

Videos

Message boards and forums

Chat rooms

Blogs

Facebook

Twitter

YouTube

Event marketing and sponsorship

Sports

Arts

Entertainment

Fairs and festivals

Cause-related

Mobile

SMS & MMS messages

Ads

Location-based services

Publicity and public relations

Word-of-mouth

Personal selling

Figure 6-1 Marketing Communications Options

The New Media Environment

Although advertising and other communication options can play different roles in the marketing program, one important purpose they all serve is to contribute to brand equity. According to the customer-based brand equity model, marketing communications can contribute to brand equity in a number of different ways: by creating awareness of the brand; linking points-of-parity and points-of-difference associations to the brand in consumers’ memory; eliciting positive brand judgments or feelings; and facilitating a stronger consumer–brand connection and brand resonance. In addition to forming the desired brand knowledge structures, marketing communication programs can provide incentives eliciting the differential response that makes up customer-based brand equity.

The flexibility of marketing communications comes in part from the number of different ways they can contribute to brand equity. At the same time, brand equity helps marketers determine how to design and implement different marketing communication options. In this chapter, we consider how to develop marketing communication programs to build brand equity. We will assume the other elements of the marketing program have been properly put into place. Thus, the optimal brand positioning has been defined—especially in terms of the desired target market—and product, pricing, distribution, and other marketing program decisions have largely been made.

Complicating the picture for marketing communications programs, however, is that fact that the media environment has changed dramatically in recent years. Traditional advertising media such as TV, radio, magazines, and newspapers seem to be losing their grip on consumers due to increased competition for consumer attention. The digital revolution offers a host of new ways for consumers to learn and talk about brands with companies or with each other.

This changing media landscape has forced marketers to reevaluate how they should best communicate with consumers.2 Consider how Ford defied convention in launching a new vehicle.

Fiesta

The Ford Fiesta was a vital new product introduction for the company, given the tough economic times and financial challenges faced by the auto industry. Its success was due, in part, to a comprehensive, carefully integrated marketing communications program. Before the U.S. launch took place in April 2010, 150 Fiestas toured the country for test drives, and 100 were given to bloggers for six months to allow them to share their experiences. People were chosen based on their online experience with blogging and social-media friends and a video they submitted testifying to their desire for adventure. After six months, the campaign had 4.3 million YouTube views, over 500,000 Flickr views, over 3 million Twitter impressions, and 50,000 interested potential customers, 97 percent of whom didn’t already own a Ford. After launch, more traditional advertising and other forms of promotion kicked in, but a second phase of the social media campaign was also introduced. Twenty pairs of agents selected from 1,000 applicants were assigned to a major market where they tweeted messages and promoted the Fiesta virally via a series of online and local challenges.3

Challenges in Designing Brand-Building Communications

The new media environment has further complicated marketers’ perennial challenge to build effective and efficient marketing communication programs. The Fiesta example illustrates the creativity and scope of what will characterize successful twenty-first century marketing communication programs. Skillfully designed and implemented marketing communications programs require careful planning and a creative knack. Let’s first consider a few useful tools to provide some perspective.

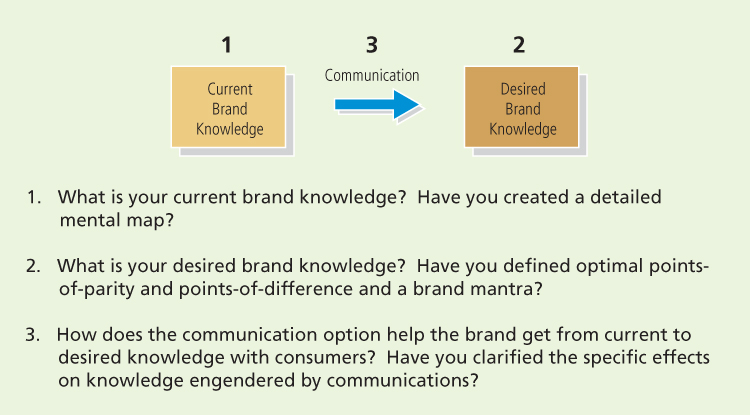

Perhaps the simplest—but most useful—way to judge any communication option is by its ability to contribute to brand equity. For example, how well does a proposed ad campaign contribute to brand awareness or to creating, maintaining, or strengthening certain brand associations? Does a sponsorship cause consumers to have more favorable brand judgments and feelings? To what extent does an online promotion encourage consumers to buy more of a product? At what price premium? Figure 6-2 displays a simple three-step model for judging the effectiveness of advertising or any communication option to build brand equity.

Figure 6-2 Simple Test for Marketing Communication Effectiveness

Information Processing Model of Communications

To provide some perspective, let’s consider in more depth the process by which marketing communications might affect consumers. A number of different models have been put forth over the years to explain communications and the steps in the persuasion process—recall the discussion on the hierarchy of effects model from Brand Focus 2.0. For example, for a person to be persuaded by any form of communication (a TV advertisement, newspaper editorial, or blog posting), the following six steps must occur:4

-

Exposure: A person must see or hear the communication.

-

Attention: A person must notice the communication.

-

Comprehension: A person must understand the intended message or arguments of the communication.

-

Yielding: A person must respond favorably to the intended message or arguments of the communication.

-

Intentions: A person must plan to act in the desired manner of the communication.

-

Behavior: A person must actually act in the desired manner of the communication.

You can appreciate the challenge of creating a successful marketing communication program when you realize that each of the six steps must occur for a consumer to be persuaded. If there is a breakdown or failure in any step along the way, then successful communication will not result. For example, consider the potential pitfalls in launching a new advertising campaign:

-

A consumer may not be exposed to an ad because the media plan missed the mark.

-

A consumer may not notice an ad because of a boring and uninspired creative strategy.

-

A consumer may not understand an ad because of a lack of product category knowledge or technical sophistication, or because of a lack of awareness and familiarity about the brand itself.

-

A consumer may fail to respond favorably and form a positive attitude because of irrelevant or unconvincing product claims.

-

A consumer may fail to form a purchase intention because of a lack of an immediate perceived need.

-

A consumer may fail to actually buy the product because he or she doesn’t remember anything from the ad when confronted with the available brands in the store.

To show how fragile the whole communication process is, assume that the probability of each of the six steps being successfully accomplished is 50 percent—most likely an extremely generous assumption. The laws of probability suggest that the likelihood of all six steps successfully occurring, assuming they are independent events, is 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5, which equals 1.5625 percent. If the probability of each step’s occurring, on average, were a more pessimistic 10 percent, then the joint probability of all six events occurring is .000001. In other words, only 1 in 1,000,000! No wonder advertisers sometimes lament the limited power of advertising.

One implication of the information processing model is that to increase the odds for a successful marketing communications campaign, marketers must attempt to increase the likelihood that each step occurs. For example, from an advertising standpoint, the ideal ad campaign would ensure that:

-

The right consumer is exposed to the right message at the right place and at the right time.

-

The creative strategy for the advertising causes the consumer to notice and attend to the ad but does not distract from the intended message.

-

The ad properly reflects the consumer’s level of understanding about the product and the brand.

-

The ad correctly positions the brand in terms of desirable and deliverable points-of-difference and points-of-parity.

-

The ad motivates consumers to consider purchase of the brand.

-

The ad creates strong brand associations to all these stored communication effects so that they can have an effect when consumers are considering making a purchase.

Clearly, marketers need to design and execute marketing communication programs carefully if they are to have the desired effects on consumers.

Role of Multiple Communications

How much and what kinds of marketing communications are necessary? Economic theory suggests placing dollars into a marketing communication budget and across communication options according to marginal revenue and cost. For example, the communication mix would be optimally distributed when the last dollar spent on each communication option generated the same return.

Because such information may be difficult to obtain, however, other models of budget allocation emphasize more observable factors such as stage of brand life cycle, objectives and budget of the firm, product characteristics, size of budget, and media strategy of competitors. These factors are typically contrasted with the different characteristics of the media.

For example, marketing communication budgets tend to be higher when there is low channel support, much change in the marketing program over time, many hard-to-reach customers, more complex customer decision making, differentiated products and nonhomogeneous customer needs, and frequent product purchases in small quantities.5

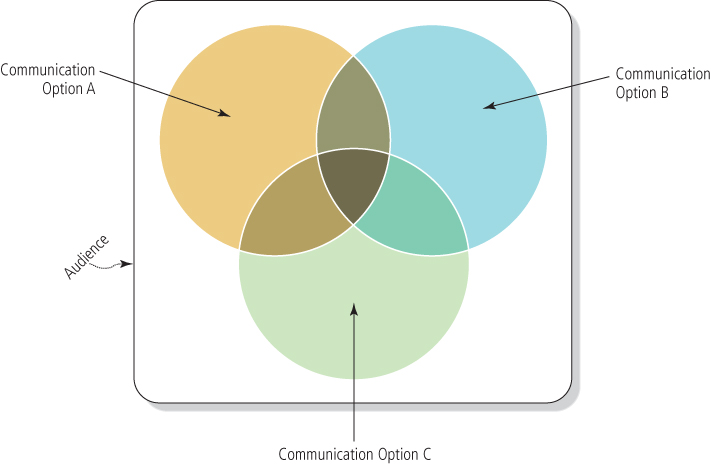

Besides these efficiency considerations, different communication options also may target different market segments. For example, advertising may attempt to bring new customers into the market or attract competitors’ customers to the brand, whereas promotions might attempt to reward loyal users of the brand.

Invariably, marketers will employ multiple communications to achieve their goals. In doing so, they must understand how each communication option works and how to assemble and integrate the best set of choices. The following section presents an overview and critique of four major marketing communication options from a brand-building perspective.

Four Major Marketing Communication Options

Our contention is that in the future there will be four vital ingredients to the best brand-building communication programs: (1) advertising and promotion, (2) interactive marketing, (3) events and experiences, and (4) mobile marketing. We consider each in turn.

Advertising

Advertising is any paid form of nonpersonal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or services by an identified sponsor. Although it is a powerful means of creating strong, favorable, and unique brand associations and eliciting positive judgments and feelings, advertising is controversial because its specific effects are often difficult to quantify and predict. Nevertheless, a number of studies using very different approaches have shown the potential power of advertising on brand sales. As Chapter 1 noted, the latest recession provided numerous examples of brands benefiting from increased advertising expenditures. A number of prior research studies are consistent with that view.6

Given the complexity of designing advertising—the number of strategic roles it might play, the sheer number of specific decisions to make, and its complicated effect on consumers—it is difficult to provide a comprehensive set of detailed managerial guidelines. Different advertising media clearly have different strengths, however, and therefore are best suited to play certain roles in a communication program. Brand Focus 6.0 provides some empirical generalizations about advertising. Now we’ll highlight some key issues about each type of advertising medium in turn.

Television

Television is a powerful advertising medium because it allows for sight, sound, and motion and reaches a broad spectrum of consumers. Virtually all U.S. households have televisions, and the average hours viewed per person per week in the United States in 2010 was 34 hours, an all-time high.7 The wide reach of TV advertising translates to low cost per exposure.

Pros & Cons

From a brand equity perspective, TV advertising has two particularly important strengths. First, it can be an effective means of vividly demonstrating product attributes and persuasively explaining their corresponding consumer benefits. Second, TV advertising can be a compelling means for dramatically portraying user and usage imagery, brand personality, emotions, and other brand intangibles.

On the other hand, television advertising has its drawbacks. Because of the fleeting nature of the message and the potentially distracting creative elements often found in a TV ad, consumers can overlook product-related messages and the brand itself. Moreover, the large number of ads and nonprogramming material on television creates clutter that makes it easy for consumers to ignore or forget ads. The large number of channels creates fragmentation, and the widespread existence of digital video recorders gives viewers the means to skip commercials.

Another important disadvantage of TV ads is the high cost of production and placement. In 2010, for example, a 30-second spot to air during the popular American Idol on FOX ran between $360,000 and $490,000. A 30-second spot on even a new network show typically costs over $100,000.8 Although the price of TV advertising has skyrocketed, the share of the prime time audience for the major networks has steadily declined. By any number of measures, the effectiveness of any one ad, on average, has diminished.

Nevertheless, properly designed and executed TV ads can affect sales and profits. For example, over the years, one of the most consistently successful TV advertisers has been Apple. The “1984” ad for the introduction of its Macintosh personal computer—portraying a stark Orwellian future with a feature film look—ran only once on TV, but is one of the best-known ads ever. In the years that followed, Apple advertising successfully created awareness and image for a series of products, more recently with the acclaimed “Get a Mac” global ad campaign.9

Apple

Apple Computer’s highly successful “Get a Mac” ad campaign—also known as “Mac vs. PC”—featured two actors bantering about the merits of their respective brands: one is hip looking (Apple), the other nerdy looking (PC). The campaign quickly went global. Apple, recognizing its potential, dubbed the ads for Spain, France, Germany, and Italy; however, it chose to reshoot and rescript for the United Kingdom and Japan—two important markets with unique advertising and comedy cultures. The UK ads followed a similar formula but used two well-known actors in character and tweaked the jokes to reflect British humor. The Japanese ads avoided direct comparisons and were more subtle in tone. Played by comedians from a local troupe called the Rahmens, the two characters were more similar in nature but represented work (PC) versus home (Mac). Creative but effective in any language, the ads helped provide a stark contrast between the two brands, making the Apple brand more relevant and appealing to a whole new group of consumers.

Guidelines.

In designing and evaluating an ad campaign, marketers should distinguish the message strategy or positioning of an ad (what the ad attempts to convey about the brand) from its creative strategy (the way the ad expresses the brand claims). Designing effective advertising campaigns is both an art and a science: The artistic aspects relate to the creative strategy of the ad and its execution; the scientific aspects relate to the message strategy and the brand claim information the ad contains. Thus, as Figure 6-3 describes, the two main concerns in devising an advertising strategy are as follows:

-

Defining the proper positioning to maximize brand equity

-

Identifying the best creative strategy to communicate or convey the desired positioning

DEFINE POSITIONING TO ESTABLISH BRAND EQUITY

Competitive frame of reference

Nature of competition

Target market

Point-of-parity attributes or benefits

Category

Competitive

Correlational

Point-of-difference attributes or benefits

Desirable

Deliverable

Differentiating

IDENTIFY CREATIVE STRATEGY TO COMMUNICATE POSITIONING CONCEPT

Informational (benefit elaboration)

Problem–solution

Demonstration

Product comparison

Testimonial (celebrity or unknown consumer)

Transformational (imagery portrayal)

Typical or aspirational usage situation

Typical or aspirational user of product

Brand personality and values

Motivational ("borrowed interest" techniques)

Humor

Warmth

Sex appeal

Music

Fear

Special effects

Figure 6-3 Factors in Designing Effective Advertising Campaigns

Source: Based in part on an insightful framework put forth in John R. Rossiter and Larry Percy, Advertising and Promotion Management, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997).

Chapter 3 described a number of issues with respect to positioning strategies to maximize brand equity. Creative strategies tend to be either largely informational, elaborating on a specific product-related attribute or benefit, or largely transformational, portraying a specific non-product-related benefit or image.10 These two general categories each encompass several different specific creative approaches.

Regardless of which general creative approach marketers take, however, certain motivational or “borrowed interest” devices can attract consumers’ attention and raise their involvement with an ad. These devices include cute babies, frisky puppies, popular music, well-liked celebrities, amusing situations, provocative sex appeals, and fear-inducing threats. Many believe such techniques are necessary in the tough new media environment characterized by low-involvement consumer processing and much competing ad and programming clutter.

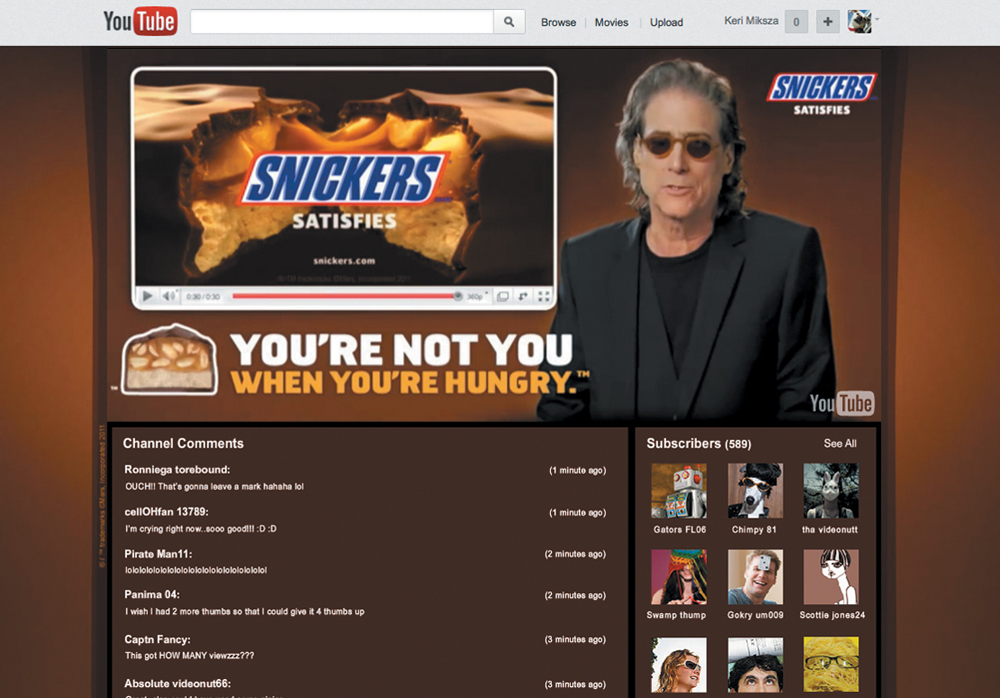

Unfortunately, these attention-getting tactics are often too effective and distract from the brand or its product claims. Thus, the challenge in arriving at the best creative strategy is figuring out how to break through the clutter to attract the attention of consumers but still deliver the intended message. Consider how the SNICKERS® candy bar achieved that.

Snickers® Brand

Facing slumping sales, SNICKERS® needed to build on its key point-of-difference as a deliciously filling hunger-satisfier to extend its reach beyond its core audience of young males. With a campaign theme of “You’re Not You When You’re Hungry®,” humorous ads were created that showed everyday people acting like—and literally becoming—different people in different situations because of their hunger. Only when they eat a SNICKERS® bar do they snap back to reality and become themselves again. In the high-profile 2010 Super Bowl launch ad for the U.S. market, a guy in a playground football game is snidely told he is playing like famed comedienne Betty White—who actually is shown playing—until he gets his bite of SNICKERS®. In a follow-up spot, one of four guys on a road trip is told he is acting like a diva in the form of legendary soul singer Aretha Franklin until he is given a SNICKERS® bar. Strong PR, complementary print, and extensive digital activation and Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter presence all further reinforced the message. The well-conceived and executed campaign received an EFFIE award from the American Marketing Association in recognition of its marketplace sales success.11

Humorous ads for SNICKERS® have reinforced its value as a hunger satisfier.

Source: SNICKERS® is a registered trademark of Mars, Incorporated and its affiliates. This trademark is used with permission. Mars, Incorporated is not associated with Pearson Education, Inc. The SNICKERS® advertisement is printed with permission of Mars, Incorporated.

What makes an effective TV ad?12 Fundamentally, a TV ad should contribute to brand equity in some demonstrable way, for example, by enhancing awareness, strengthening a key association or adding a new association, or eliciting a positive consumer response. Earlier, we identified six broad information-processing factors as affecting the success of advertising: consumer targeting, the ad creative, consumer understanding, brand positioning, consumer motivation, and ad memorability.

Although managerial judgment using criteria such as these can and should be employed in evaluating advertising, research also can play a productive role. Advertising strategy research is often invaluable in clarifying communication objectives, target markets, and positioning alternatives. To evaluate the effectiveness of message and creative strategies, copy testing is often conducted, in which a sample of consumers is exposed to candidate ads and their reactions are gauged in some manner.

Unfortunately, copy-testing results vary considerably depending on exactly how tests are conducted. Consequently, the results must be interpreted as only one possible data point that should be combined with managerial judgment and other information in evaluating the merits of an ad. Copy testing is perhaps most useful when managerial judgment reveals some fairly clear positive and negative aspects to an ad and is therefore somewhat inconclusive. In this case, copy-testing research may shed some light on how these various conflicting aspects “net out” and collectively affect consumer processing.

Regardless, copy-testing results should not be seen as a means of making a “go” or “no go” decision; ideally, they should play a diagnostic role in helping to understand how an ad works. As an example of the potential fallibility of pretesting, consider NBC’s experiences with the popular TV series Seinfeld.

Seinfeld

In October 1989, The Seinfeld Chronicles, as it was called then, was shown to several groups of viewers in order to gauge the show’s potential, like most television pilot projects awaiting final network approval. The show tested badly—very badly. The summary research report noted that “no segment of the audience was eager to watch the show again.” The reaction to Seinfeld himself was “lukewarm” because his character was seen as “powerless, dense, and naïve.” The test report also concluded that “none of the supports were particularly liked and viewers felt that Jerry needed a better back-up ensemble.” Despite the weak reaction, NBC decided to go ahead with what became one of the most successful television shows of the 1990s. Although NBC also changed its testing methods, this experience reinforces the limitations of testing and the dangers of relying on single numbers.13

Future Prospects.

In the new Internet era, the future of television and traditional mass marketing advertising is uncertain as top marketers weigh their new communication options. Some “New Year’s Resolutions” drafted for 2010 reveal their changing mind-set:14

-

Richard Gerstein, senior VP of marketing at Sears: “Stay focused on creating personalized digital relationships with our customers by meeting their individual needs in an integrated way through our stores, Web sites, call center, and innovative mobile shopping sites.”

-

Keith Levy, VP of marketing at Anheuser-Busch: “To find the next Facebook or Twitter phenomenon . . . making sure we’re in the places our consumers are increasingly headed and being there in an authentic way.”

Although digital has captured the imagination of marketers everywhere, at least for some, the power of TV ads remains. In a series of interviews in 2011, many CMOs also continued to show their support for TV advertising. Procter & Gamble CMO Marc Pritchard put it directly when he said, “TV will continue to be an essential part of our marketing mix to reach people with our brands.”15 TV spending is forecast to continue to make up almost 40 percent of all U.S. ad spending through 2015.

Radio

Radio is a pervasive medium: 93 percent of all U.S. consumers 12 years and older listen to the radio daily and, on average, for over 15 hours a week, although often only in the background.16 Perhaps the main advantage to radio is flexibility—stations are highly targeted, ads are relatively inexpensive to produce and place, and short closings allow for quick responses.

Radio is a particularly effective medium in the morning and can effectively complement or reinforce TV ads. Radio also enables companies to achieve a balance between broad and localized market coverage. Obvious disadvantages of radio, however, are the lack of visual image and the relatively passive nature of consumer processing that results. Several brands, however, have effectively built brand equity with radio ads.

Motel 6

One notable radio ad campaign is for Motel 6, the nation’s largest budget motel chain, which was founded in 1962 when the “6” stood for $6 a night. After finding its business fortunes hitting bottom in 1986 with an occupancy rate of only 66.7 percent, Motel 6 made a number of marketing changes, including the launch of a radio campaign of humorous 60-second ads featuring folksy contractor-turned-writer Tom Bodett. Containing the clever tag line “We’ll Leave the Light on for You,” the campaign is credited with a rise in occupancy and a revitalization of the brand that continues to this day.17

Using the clever slogan, “We’ll Leave the Light on for You,” radio—complemented by magazine ads like this—has been a highly effective brand-building medium for Motel 6.

Source: Accor North America

What makes an effective radio ad?18 Radio has been less studied than other media. Because of its low-involvement nature and limited sensory options, advertising on radio often must be fairly focused. For example, the advertising pioneer David Ogilvy believed four factors were critical:19

-

Identify your brand early in the commercial.

-

Identify it often.

-

Promise the listener a benefit early in the commercial.

-

Repeat it often.

Nevertheless, radio ads can be extremely creative. Some see the lack of visual images as a plus because they feel the clever use of music, sounds, humor, and other creative devices can tap into the listener’s imagination in a way that creates powerfully relevant and liked images.

Print media has taken a huge hit in recent years as more and more consumers choose to collect information and seek entertainment online. In response, publishers are doing their own digital innovation in the form of iPad apps and a stronger Web presence.

Print media does offer a stark contrast to broadcast media. Most importantly, because they are self-paced, magazines and newspapers can provide detailed product information. At the same time, the static nature of the visual images in print media makes it difficult to provide dynamic presentations or demonstrations. Another disadvantage of print advertising is that it can be a fairly passive medium.

Pros & Cons.

The two main print media—magazines and newspapers—have many of the same advantages and disadvantages. Magazines are particularly effective at building user and usage imagery. They can also be highly engaging: one study showed that consumers are more likely to view magazine ads as less intrusive, more truthful, and more relevant than ads in other media and are less likely to multitask while reading.20

Newspapers, however, are more timely and pervasive. Daily newspapers are read by 30 percent of the population—although that number has been declining for years as more consumers go online to get their news—and tend to be used for local (especially retailer) advertising.21 On the other hand, although advertisers have some flexibility in designing and placing newspaper ads, poor reproduction quality and short shelf life can diminish some of the possible impact of newspaper advertising. These are disadvantages that magazine advertising usually doesn’t share.

Although print advertising is particularly well suited to communicate product information, it can also effectively communicate user and usage imagery. Fashion brands such as Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, and Guess have also created strong nonproduct associations through print advertising. Some brands attempt to communicate both product benefits and user or usage imagery in their print advertising, for example, car makers such as Ford, Volkswagen, and Volvo or cosmetics makers such as Maybelline and Revlon.

One of the longest-running and perhaps most successful print ad campaigns ever is for Absolut vodka.22

Absolut

In 1980, Absolut was a tiny brand, selling 100,000, nine-liter cases a year. Research pointed out a number of liabilities for the brand: the name was seen as too gimmicky; the bottle shape was ugly, and bartenders found it hard to pour; shelf prominence was limited; and there was no credibility for a vodka brand made in Sweden. Michel Roux, president of Carillon (Absolut’s importer), and TBWA (Absolut’s New York ad agency) decided to use the oddities of the brand—its quirky name and bottle shape—to create brand personality and communicate quality and style in a series of creative print ads. Each ad in the campaign visually depicted the product in an unusual fashion and verbally reinforced the image with a simple, two-word headline using the brand name and some other word in a clever play on words. For example, the first ad showed the bottle prominently displayed, crowned by an angel’s halo, with the headline “Absolut Perfection” appearing at the bottom of the page. Follow-up ads explored various themes (seasonal, geographic, celebrity artists) but always attempted to put forth a fashionable, sophisticated, and contemporary image. By 2001, Absolut had become the leading imported vodka in the United States, and by 2006, it was the third-largest premium spirits brand in the world, with sales of 9.8 million nine-liter cases. Facing slowing sales in 2007, however, the firm launched its first new campaign in 25 years, “In an Absolut World.” The goal of the campaign was to focus on the uniqueness of the brand by showing a fantasy world where lying leaders are exposed by their Pinocchio noses, protesters and the police wage street fights with feather pillows, nice Manhattan apartments cost $300 a month, and it takes only one lap in a pool to turn fat into muscle. Later ads expanded the meaning of an “Absolut World” to include special, offbeat, or unusual events, people, and things by including celebrities such as Kate Beckinsale and Zooey Deschanel. In 2011, a new multimedia campaign, ABSOLUT BLANK, was launched with the tag line, “It All Starts with an Absolute Blank.” Twenty artists—from drawing, painting, and sculpting to film making and digital art—used the iconic Absolut bottle as a blank canvas and creatively filled it with their artistic expression.

Absolut’s new print ad campaign has returned to a creative strategy that emphasizes the product’s packaging and appearance. This ad featured artist Dave Kinsey.

Source: © The Absolut Company AB. Used under permission from The Absolut Company AB.

Guidelines.

What makes an effective print ad? The evaluation criteria we noted earlier for television advertising apply, but print advertising has some special requirements and rules. For example, research on print ads in magazines reveals that it is not uncommon for two-thirds of a magazine audience to not even notice any one particular print ad, or for only 10 percent or so of the audience to read much of the copy of any one ad. Many readers only glance at the most visible elements of a print ad, making it critical that an ad communicate clearly, directly, and consistently in the ad illustration and headline. Finally, many consumers can easily overlook the brand name if it is not readily apparent. We can sum the creative guidelines for print ads in three simple criteria: clarity, consistency, and branding.

Direct Response

In contrast to advertising in traditional broadcast and print media, which typically communicates to consumers in a nonspecific and nondirective manner, direct response uses mail, telephone, Internet, and other contact tools to communicate with or solicit a response from specific customers and prospects. Direct response can take many forms and is not restricted to solicitations by mail, telephone, or even within traditional broadcast and print media.

Direct mail still remains popular, with U.S. businesses generating $571 billion in sales from direct mail in 2010.23 Marketers are exploring other options, though. One increasingly popular means of direct marketing is infomercials, formally known as direct response TV marketing.24 In a marketing sense, infomercials attempt to combine the sell of commercials with the draw of educational information and entertainment. We can therefore think of them as a cross between a sales call and a television ad. According to Infomercial DRTV, a trade Web site, infomercials are typically 28 minutes and 30 seconds long with an average cost in the $150,000–250,000 range (although production can cost as little as $75,000 and as much as $500,000).25

Starting with infomercials, although now moving online and also employing social media, Guthy-Renker enjoys about $800 million in revenue from its Proactiv acne treatment, endorsed by celebrities Justin Bieber, Jennifer Love-Hewitt, Katy Perry, Avril Lavigne, and Jenna Fischer. Many infomercial products are now showing up in stores carrying little “As Seen on TV” signs. Telebrands has sold 35 million of the PedEgg used to smooth rough feet and generates 90 percent of sales of all its products from major retailers such as CVS and Target. By 2014, direct-response TV marketing is expected to drive sales of $174 billion—a 30% increase from 2010 levels.26

Guidelines.

The steady growth of direct marketing in recent years is a function of technological advances like the ease of setting up toll-free numbers and Web sites; changes in consumer behavior, such as the increased demand for convenience; and the needs of marketers, who want to avoid wasteful communications to nontarget customers or customer groups. The advantage of direct response is that it makes it easier for marketers to establish relationships with consumers.

Direct communications through electronic or physical newsletters, catalogs, and so forth allow marketers to explain new developments with their brands to consumers on an ongoing basis as well as allow consumers to provide feedback to marketers about their likes and dislikes and specific needs and wants. By learning more about customers, marketers can fine-tune marketing programs to offer the right products to the right customers at the right time. In fact, direct marketing is often seen as a key component of relationship marketing—an important marketing trend we reviewed in Chapter 5. Some direct marketers employ what they call precision marketing—combining data analytics with strategic messages and compelling colors and designs in their communications.27

As the name suggests, the goal of direct response is to elicit some type of behavior from consumers; given that, it is easy to measure the effects of direct marketing efforts—people either respond or they do not. The disadvantages to direct response, however, are intrusiveness and clutter. To implement an effective direct marketing program, marketers need the three critical ingredients of (1) developing an up-to-date and informative list of current and potential future customers, (2) putting forth the right offer in the right manner, and (3) tracking the effectiveness of the marketing program. To improve the effectiveness of direct marketing programs, many marketers are embracing database marketing, as highlighted by The Science of Branding 6-1.

Place

The last category of advertising is also often called “nontraditional,” “alternative,” or “support” advertising, because it has arisen in recent years as a means to complement more traditional advertising media. Place advertising, also called out-of-home advertising, is a

broadly defined category that captures advertising outside traditional media. Increasingly, ads and commercials are showing up in unusual spots, sometimes as parts of experiential marketing programs.

The rationale is that because traditional advertising media—especially television advertising—are becoming less effective, marketers are better off reaching people in other environments, such as where they work, play, and, of course, shop. Out-of-home advertising picked up as the economy started to pick up in 2010, when it was estimated that $6.1 billion was spent.28 Some of the options include billboards and posters; movies, airlines, lounges, and other places; product placement; and point-of-purchase advertising.

Billboards and Posters.

Billboards have a long history but have been transformed over the years and now employ colorful, digitally produced graphics, backlighting, sounds, movement, and unusual—even three-dimensional—images to attract attention. The medium has improved in terms of effectiveness (and measurability), technology (some billboards are now digitized), and provide a good opportunity for companies to sync their billboard strategies with mobile advertising.

Billboard-type poster ads are now showing up everywhere in the United States each year to increase brand exposure and goodwill. Transit ads on buses, subways, and commuter trains—around for years—have now become a valuable means to reach working women. Street furniture (bus shelters, kiosks, and public areas) has also become a fast-growing area. In Japan, cameras and sensors are being added to signs and electronic public displays so that—combined with cell-phone technology—they can become more interactive and personalized.29

Billboards do not even necessarily have to stay in one place. Marketers can buy ad space on billboard-laden trucks that are driven around all day in marketer-selected areas. Oscar Mayer sends seven “Wienermobiles” traveling across the country each year. New York City became the

Oscar Meyer’s Weinermobile, with its two Hotdoggers drivers, tour the country and make appearances at various events.

Source: ZUMA Press/Newscom

first major city to allow its taxi cabs to advertise via onboard television screens. Between 2009 and 2010, the number of taxi advertisers doubled, and included brands such as AOL, Citibank, and Sprint. Research has shown that passengers keep the TVs on 85 percent of the time.30

Advertisers can now buy space in stadiums and arenas and on garbage cans, bicycle racks, parking meters, airport luggage carousels, elevators, gasoline pumps, the bottom of golf cups, airline snacks, and supermarket produce in the form of tiny labels on apples and bananas. Leaving no stone unturned, advertisers can even buy space in toilet stalls and above urinals, which, according to research studies, office workers visit an average of three to four times a day for roughly four minutes per visit. At Chicago O’Hare airport, digital commercials are now being shown in 150 bathroom mirrors above lavatory sinks.31 Figure 6-4 displays some of the most successful outdoor advertisers.

Movies, Airlines, Lounges, and Other Places.

Increasingly, advertisers are placing traditional TV and print ads in unconventional places. Companies such as Whittle Communication and Turner Broadcasting have tried placing TV and commercial programming in classrooms, airport lounges, and other public places. Airlines now offer media-sponsored audio and video programming that accepts advertising (USA Today Sky Radio and National Geographic Explorer) and include catalogs in seat pockets for leading mail-order companies (SkyMall magazine). Movie theater chains such as Loews Cineplex now run 30-, 60-, or 90-second ads on 2,000-plus screens. Although the same ads that appear on TV or in magazines often appear in these unconventional places, many advertisers believe it is important to create specially designed ads for these out-of-home exposures to better meet consumer expectations.

Chick-fil-A (2006)

Walt Disney Company (2007)

Altoids (2008)

Absolut (2009)

MINI Cooper (2010)

Cracker Barrel Old Country Store (2011)

Figure 6-4 Obie Hall of Fame Winners (as selected by the Outdoor Advertising Association of America)

Product Placement.

Many major marketers pay fees of $50,000–100,000 and even higher so their products can make cameo appearances in movies and on television, with the exact fee depending on the amount and nature of the brand exposure. This practice got a boost in 1982 when—after Mars declined an offer for use of its M&M’s brand—sales of Reese’s Pieces increased 65 percent after the candy appeared prominently in the blockbuster movie E.T.: The Extraterrestrial.32

More recently, many brands such as Chase, Hilton, AT Cross, and Heineken have paid to be featured in the popular TV series Mad Men.33 Marketers combine product placements with special promotions to publicize a brand’s entertainment tie-ins and create “branded entertainment.” For example, BMW complemented product placement in the James Bond film Goldeneye with an extensive direct mail and advertising campaign to help launch its Z3 roadster.

Some firms benefit from product placement at no cost by either supplying their product to the movie company in return for exposure or simply because of the creative demands of the storyline. Mad Men has also prominently featured such iconic brands as Cadillac, Kodak, and Utz potato chips for free because of plot necessities. To test the effects of product placement, marketing research companies such as CinemaScore conduct viewer exit surveys to determine which brands were actually noticed during movie showings.

Point of Purchase.

Myriad possibilities have emerged in recent years as ways to communicate with consumers at the point of purchase. In-store advertising includes ads on shopping carts, cart straps, aisles, or shelves as well as promotion options such as in-store demonstrations, live sampling, and instant coupon machines. Point-of-purchase radio provides FM-style programming and commercial messages to thousands of food stores drugstores nationwide. Programming includes a store-selected music format, consumer tips, and commercials. The Walmart Smart Network is beamed to over 2,700 of the retail giant’s stores and is a mixture of information content and advertising.34

The appeal of point-of-purchase advertising lies in the fact that, as numerous studies have shown, consumers in many product categories make the bulk of their final brand decisions in the store. In-store media are designed to increase the number and nature of spontaneous and planned buying decisions. One company placing ads on the entryway security panels of major retail chains reported that the advertised brands experienced an average increase in sales of 20 percent over the four-week period in which their ads appeared.35

Guidelines.

Nontraditional or place media present some interesting options for marketers to reach consumers in new ways. Ads now can appear virtually any place where consumers have a

Mad Men has been popular not just with viewers—a number of marketers have paid for product placement for their brands.

Source: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy

few spare minutes or even seconds and thus enough time to notice them. The main advantage of nontraditional media is that they can reach a very precise and captive audience in a cost-effective and increasingly engaging manner.

Because the audience must process out-of-home ads quickly, however, the message must be simple and direct. In fact, outdoor advertising is often called the “15-second sell.” In noting how out-of-home aligns with twenty-first century consumers, one commentator observed that with people on-the-go and wanting content in short bursts, “Billboards are the original tweets—you get a quick image or piece of knowledge than move on.”36 In that regard, strategically, out-of-home advertising is often more effective at enhancing awareness or reinforcing existing brand associations than at creating new ones.

The challenge with nontraditional media is demonstrating their reach and effectiveness through credible, independent research. Another danger of nontraditional media is consumer backlash against overcommercialization. Perhaps because of the sheer pervasiveness of advertising, however, consumers seem to be less bothered by nontraditional media now than in the past.

Consumers must be favorably affected in some way to justify the marketing expenditures for nontraditional media, and some firms offering ad placement in supermarket checkout lines, fast-food restaurants, physicians’ waiting rooms, health clubs, and truck stops have suspended business at least in part because of lack of consumer interest. The bottom line, however, is that there will always be room for creative means of placing the brand in front of consumers—the possibilities are endless.

Promotion

Although they do very different things, advertising and promotion often go hand-in-hand. Sales promotions are short-term incentives to encourage trial or usage of a product or service.37 Marketers can target sales promotions to either the trade or end consumers. Like advertising, sales promotions come in all forms. Whereas advertising typically provides consumers a reason to buy, sales promotions offer consumers an incentive to buy. Thus, sales promotions are designed to do the following:

-

Change the behavior of the trade so that they carry the brand and actively support it

-

Change the behavior of consumers so that they buy a brand for the first time, buy more of the brand, or buy the brand earlier or more often

Analysts maintain that the use of sales promotions grew in the 1980s and 1990s for a number of reasons. Brand management systems with quarterly evaluations were thought to encourage short-term solutions, and an increased need for accountability seemed to favor communication tools like promotions, whose behavioral effects are more quickly and easily observed than the often “softer” perceptual effects of advertising. Economic forces worked against advertising effectiveness as ad rates rose steadily despite what marketers saw as an increasingly cluttered media environment and fragmented audience. Consumers were thought to be making more in-store decisions, and to be less brand loyal and more immune to advertising than in the past. Many mature brands were less easily differentiated. On top of it all, retailers became more powerful.

For all these reasons, some marketers began to see consumer and trade promotions as a more effective means than advertising to influence the sales of a brand. There clearly are advantages to sales promotions. Consumer sales promotions permit manufacturers to price discriminate by effectively charging different prices to groups of consumers who vary in their price sensitivity. Besides conveying a sense of urgency to consumers, carefully designed promotions can build brand equity through information or actual product experience that helps to create strong, favorable, and unique associations. Sales promotions can encourage the trade to maintain full stocks and actively support the manufacturer’s merchandising efforts.

On the other hand, from a consumer behavior perspective, there are a number of disadvantages of sales promotions, such as decreased brand loyalty and increased brand switching, decreased quality perceptions, and increased price sensitivity. Besides inhibiting the use of franchise-building advertising or other communications, diverting marketing funds into coupons or other sales promotion sometimes has led to reductions in research and development budgets and staff. Perhaps most importantly, the widespread discounting arising from trade promotions may have led to the increased importance of price as a factor in consumer decisions, breaking down traditional brand loyalty patterns.

Another disadvantage of sales promotions is that in some cases they may merely subsidize buyers who would have bought the brand anyway. Interestingly, the more affluent, educated, suburban, and ethnically Caucasian a household is, the more likely it is to use coupons, mainly because

Some consumers have created Web sites to share their expertise in using coupons and promotions with others.

Source: Gina Lincicum/Moneywise Moms

its members are more likely to read newspapers where the vast majority of coupons appear. Sales promotions also may just subsidize “coupon enthusiasts” who use coupons frequently and broadly (on as many 188 items a year and up). Eighty-one percent of the products purchased using manufacturer coupons in the first half of 2009 came from just 19 percent of U.S. households. One “extreme” couponer prides herself on the fact that she saves 40–60 percent off her weekly grocery trips and even hosts a blog ( www.MoneyWiseMoms.com) to share her couponing tips.38

Another drawback to sales promotions is that new consumers attracted to the brand may attribute their purchase to the promotion and not to the merits of the brand per se and, as a result, may not repeat their purchase when the promotional offer is withdrawn. Finally, retailers have come to expect and now demand trade discounts. The trade may not actually provide the agreed-upon merchandising and take advantage of promotions by engaging in nonproductive activities such as forward buying (stocking up for when the promotion ends) and diversion (shipping products to areas where the promotion was not intended to go).39

Promotions have a number of possible objectives.40 With consumers, objectives may target new category users, existing category users, and/or existing brand users. With the trade, objectives may center on distribution, support, inventories, or goodwill. Next, we consider some specific issues related to consumer and trade promotions.

Consumer Promotions

Consumer promotions are designed to change the choices, quantity, or timing of consumers’ product purchases. Although they come in all forms, we distinguish between customer franchise building promotions like samples, demonstrations, and educational material, and noncustomer franchise building promotions such as price-off packs, premiums, sweepstakes, and refund offers.41 Customer franchise building promotions can enhance the attitudes and loyalty of consumers toward a brand—in other words, affect brand equity.

For example, sampling is a means of creating strong, relevant brand associations while also perhaps kick-starting word-of-mouth among consumers. Marketers are increasingly using sampling at the point of use, growing more precise about where and how they deliver samples to maximize brand equity. For a $10 monthly subscription, one new firm, Birchbox, sends consumers a box of deluxe-size samples from such notable beauty brands as Benefit, Kiehl’s, and Marc Jacobs. Members can go to the Web site to collect more information, provide feedback, and earn points for full-sized products. The beauty brands like the selectivity and customer involvement of the promotion.42

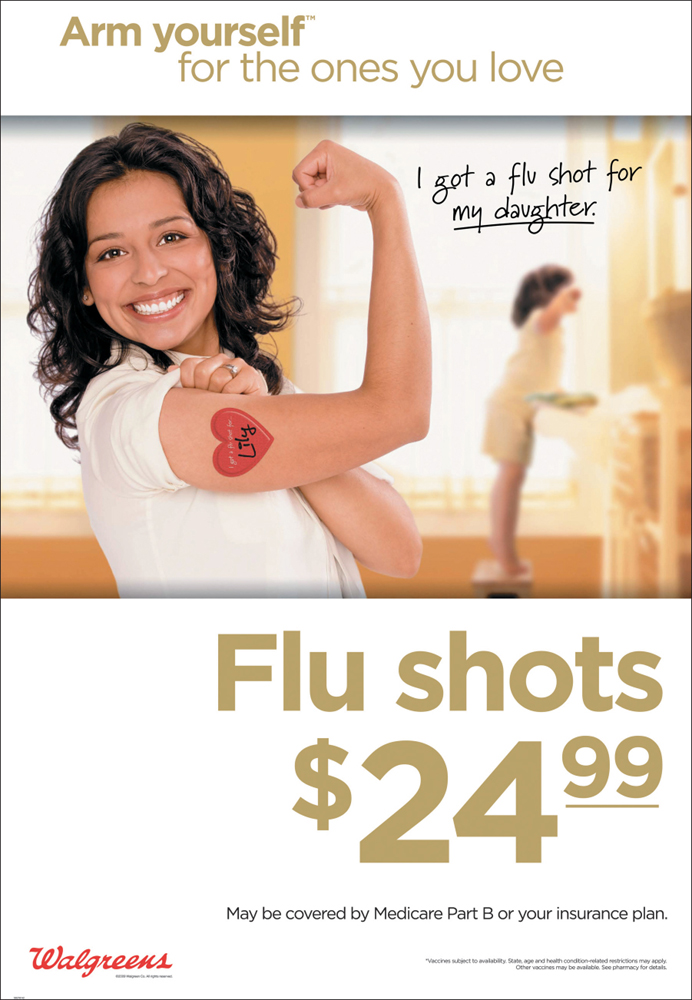

Thus, marketers increasingly judge sales promotions by their ability to contribute to brand equity as well as generate sales. Creativity is as critical to promotions as it is to advertising or any other form of marketing communications. The Promotion Marketing Association (PMA) bestows Reggie awards to recognize “superior promotional thinking, creativity, and execution across the full spectrum of promotional marketing.” In 2011, Walgreens won the Super Reggie award for its highly integrated promotional program.

Walgreens

The main objective of Walgreens’s “Arm Yourself for the Ones You Love” campaign was to convince 5 million people to get their flu shots at Walgreens in the winter of 2010. Research uncovered a subset of untapped consumers most receptive to getting a flu shot at Walgreens: “Well-Intender Moms” were 15–18 percent of the female population who had every intention of getting a flu shot the previous year but did not follow through. Busy doing things for others (including making sure their family got flu shots), they gave less priority to getting a shot for themselves. The campaign aimed to show these moms that getting their shot was a real priority and just as important to the health and well-being of their families. Walgreens’s ad agency employed a holistic communication approach, using a range of communication options from broadcast media seen at home to the Web, circulars, outdoor ads, and in-store displays. The centerpiece was an “I got my flu shot for _____” bandage/sticker so people could proudly display that they had gotten their flu shots to protect themselves and a loved one. Here are some notable activation tactics:

-

Thousands of photos of employees “showing their hearts” were used to kick off the campaign in Times Square.

-

Walgreens pharmacists appeared on national TV (MSNBC, CNN, etc.) and popular shows like The Dr. Oz Show, administering flu shots to anchors and discussing the benefits.

-

Zoned in-store messaging let shoppers know how and where they could “arm themselves.”

-

Regional print ads showcased local heroes “arming themselves.”

-

Digital and social media allowed people to show their love with their network of family and friends.

-

Street-level outdoor media ads were placed where people were most likely to be thinking about getting exposed to the flu (bus stops, airports, and hospitals).

-

“Arm Yourself” commercials brought the message to TV.

The “Arm Yourself for the Ones You Love” campaign far exceeded its goal, inspiring 5.4 million people to get their flu shot in just five weeks.43

Walgreen’s award-winning “Arm Yourself for the Ones You Love” campaign used a variety of different communication options.

Source: Walgreens

Promotion strategy must reflect the attitudes and behavior of consumers. The percentage of coupons consumers redeem dropped steadily for years—in part due to the clutter of coupons that were increasingly being distributed—before experiencing an uptick more recently: redemption rates peaked in 1992 but fell for the next 15 years until experiencing an increase in the tough economic climate of late 2008. Almost 90 percent of all coupons appear in free-standing inserts (FSIs) in Sunday newspapers.

One area of promotional growth is in-store coupons, which marketers have increasingly turned to given that their redemption rates far exceed those of traditional out-of-store coupons. Another growing area is digital coupons, whose redemption rate (6 percent) is the highest of all types of coupons and 10 times higher than for newspaper coupons. Groupon created a clever promotional scheme that has met with some apparent success; the firm also turned down a $6 billion purchase offer from Google in 2010.44

Groupon

Groupon launched in 2008 as a company offering a new marketing vehicle to businesses. By leveraging the Internet and e-mail, the company helps businesses use promotions as a form of advertisement. Specifically, Groupon maintains a large base of subscribers who receive a humorously worded daily deal—a specific percentage or dollar amount off the regular price—for a specific branded product or service. Through these e-mail discounts, Groupon offers three benefits to businesses: increased consumer exposure to the brand, the ability to price discriminate, and the creation of a “buzz factor.” For these benefits, Groupon takes a 40–50 percent cut in the process. Many promotions are offered on behalf of local retailers such as spas, fitness centers, and restaurants, but Groupon also manages deals on behalf of national brands such as Gap, Southwest Airlines, and FTD. In 2010, Groupon expanded from 1 to 35 countries, grew its subscriber base from 2 million to over 50 million, partnered with 58,000 local businesses to promote over 100,000 deals, and saved consumers over $1.5 billion. Although some businesses complain that Groupon just attracts deal-seekers and is not as effective in converting regular customers, its 2011 revenue was reported to be between $3 billion and $4 billion. Groupon now faces several competitors in the market it helped create, including LivingSocial, Bloomspot, and Buywithme. Partly in response, Groupon Now was launched. Leveraging its massive sales force to sell Groupon Now, Groupon enlists local businesses to offer time and location-specific deals that customers can obtain via the Web or their smartphone. The iPhone app for the new service has two buttons, “I’m Bored” and “I’m Hungry” to trigger possible deals in real time. For businesses, the service is a way to boost traffic at otherwise slow times. Even a popular restaurant might still consider some midday and midweek discounts knowing the place is rarely full then.

Groupon devised a completely new way to send timely promotions to consumers by digital means.

Source: Groupon Inc.

Trade Promotions

Trade promotions are often financial incentives or discounts given to retailers, distributors, and other channel members to stock, display, and in other ways facilitate the sale of a product through slotting allowances, point-of-purchase displays, contests and dealer incentives, training programs, trade shows, and cooperative advertising. Trade promotions are typically designed either to secure shelf space and distribution for a new brand, or to achieve more prominence on the shelf and in the store. Shelf and aisle positions in the store are important because they affect the ability of the brand to catch the eye of the consumer—placing a brand on a shelf at eye level may double sales over placing it on the bottom shelf.45

Because of the large amount of money spent on trade promotions, there is increasing pressure to make trade promotion programs more effective. Many firms are failing to see the brand-building value in trade promotions and are seeking to reduce and eliminate as much of their expenditures as possible.

Online Marketing Communications

The first decade of the twenty-first century has seen a headlong rush by companies into the world of interactive, online marketing communications. With the pervasive incorporation of the Internet into everyday personal and professional lives, marketers are scrambling to find the right places to be in cyberspace. The main advantages to marketing on the Web are the low cost and the level of detail and degree of customization it offers. Online marketing communications can accomplish almost any marketing communication objective and are especially valuable in terms of solid relationship building.

Leading trade publication Advertising Age’s 2010 Media Vanguard Awards for innovative uses of technology in media planning showed the wide range of online applications that exist. Among the winners were Martha Stewart for her “multimedia vision,” Financial Times for successfully managing its free Web site alongside its paid online product, Kmart for showcasing a series of online videos to promote merchandising in its stores, and Allstate’s relaunch of its Teen Driver Web site to better “speak” in teen language and use interactive games and features to engage them.

Reviewing all the guidelines for online marketing communications is beyond the scope of this text.46 Here, we’ll concentrate on three particularly crucial online brand-building tools: (1) Web sites, (2) online ads and videos, and (3) social media.

Web Sites

One of the earliest and best-established forms of online marketing communications for brands is company-created Web sites. By capitalizing on the Web’s interactive nature, marketers can construct Web sites that allow any type of consumer to choose the brand information relevant to his or her needs or desires. Even though different market segments may have different levels of knowledge and interest about a brand, a well-designed Web site can effectively communicate to consumers regardless of their personal brand or communications history.

Because consumers often go online to seek information rather than be entertained, some of the more successful Web sites are those that can convey expertise in a consumer-relevant area. For example, Web sites such as P&G’s www.pampers.com and General Mills’s www.cheerios.com offer baby care and parenting advice. Web sites can store company and product information, press releases, and advertising and promotional information as well as links to partners and key vendors. Web marketers can collect names and addresses for a database and conduct e-mail surveys and online focus groups.

Brand-building is increasingly a collaborative effort between consumers and brand marketers. As part of this process, there will be many consumer-generated Web sites and pages that may include ratings, reviews, and feedback on brands. Many consumers also post opinions and reviews or seek advice and feedback from others at commercial sites such as Yelp, TripAdvisor, and Epinions. As will be discussed in greater detail below, marketers must carefully monitor these different forums and participate where appropriate.

In creating online information sources for consumers at company Web sites, marketers must provide timely and reliable information. Web sites must be updated frequently and offer as much customized information as possible, especially for existing customers. Designing Web sites requires creating eye-catching pages that can sustain browsers’ interest, employing the latest technology and effectively communicating the brand message. Web site design is crucial, because if consumers do not have a positive experience, it may be very difficult to entice them back in the highly competitive and cluttered online world.

Online Ads and Videos

Internet advertising comes in a variety of forms—banner ads, rich-media ads, and other types of ads. Advertising on the Internet has grown rapidly—in 2010 it totaled $26 billion in the United States, surpassing newspaper advertising ($22.8 billion) to rank second behind TV advertising ($28.6 billion).47

A number of potential advantages exist for Internet advertising: It is accountable, because software can track which ads went to which sales; it is nondisruptive, so it doesn’t interrupt consumers; and it can target consumers so that only the most promising prospects are contacted, who can then seek as much or as little information as they desire. Online ads and videos also can extend the creative or legal restrictions of traditional print and broadcast media to persuasively communicate brand positioning and elicit positive judgments and feelings.

Unfortunately, there are also many disadvantages. Many consumers find it easy to ignore banner ads and screen them out with pop-up filters. The average click-through rate for a standard banner ad in the United States was 0.08 percent in 2010, although that number increased to 0.14 percent for an expandable rich media banner. Similar percentages could be found in European and Latin American countries. Even in ad categories drawing exceptional interest from consumers, the percentages barely increased (to 1.02 percent for auto in Italy, 1.9 percent for health and beauty in Poland, and the biggest percentage, almost 8 percent for restaurants in Belgium).48

Increasingly, Web messages like streaming ads are drawing closer to traditional forms of television advertising. Videos take that one step further by virtually becoming short films. BMW, one of the pioneers, created a series of highly successful made-for-the-Web movies using well-known directors such as Guy Ritchie and actors such as Madonna. The advantage of videos is the enormous potential pass-along that exists if an imaginative video strikes a chord with consumers, as was the case for Coke.49

Coke’s “Happiness Machine”

Coca-Cola’s “Open Happiness” global brand slogan and platform lends itself to many different creative ideas and executions. Besides its usual iconic ads, the company decided it also wanted to activate the idea digitally in an equally inspired way. To do so, Coca-Cola rigged up a special vending machine at St. John’s University in Queens, New York, dubbed the “Happiness Machine.” The back of the machine was connected to a storeroom filled with all the people and props necessary to execute the stunt. When unsuspecting students started to use the machine, they first just received Cokes, but after that, all kinds of goodies began to appear—a bouquet of sunflowers, balloon animals, six-foot subs, and even a hot pepperoni pizza. Their astonished and gleeful reactions were caught by hidden cameras and fed into YouTube videos that received millions of hits and even became the basis of a 30-second TV spot shown all over the world.

Coca-Cola’s “Happiness Machine” was a clever brand-building stunt that was seen virally all over the world.

Source: Photographed by Lauren Nicole Maddox

As suggested by the Coke example, the Google-owned YouTube video-sharing Web site has become an especially important vehicle for distributing videos and initiating dialogue and cultivating a community around a brand.

With Internet-connected HDTV sales climbing, video opportunities for brand building can only continue to grow.50 Any size brand can benefit. Tipp-Ex’s “A Hunter Shoots a Bear” campaign became a viral YouTube sensation with millions and millions of views. In the video, a hunter finds a bear approaching his tent but decides not to shoot it. Using Tipp-Ex, he whites out the verb “shoot” and invites viewers to add their own verbs. For each inserted verb, a stored video response is played to humorously depict the action.51

As a manifestation of permission marketing, e-mail ads in general—often including advanced features such as personalized audio messages, color photos, and streaming video—have increased in popularity. E-mail ads often receive response rates of 20–30 percent at a cost less than that of banner ads. Tracking these response rates, marketers can fine-tune their messages. The key, as with direct marketing, is to create a good customer list.

Another alternative to banner ads that a great many marketers employ is search advertising, in which users are presented with sponsored links relevant to their search words alongside unsponsored search results. Since these links are tied to specific keywords, marketers can target them more effectively than banner ads and thus generate higher response rates. Almost half of all Internet advertising in 2010 (over $12 billion) was devoted to search.52

Google pioneered search advertising and helped make it a cost-effective option for online advertisers by offering “cost-per-click” pricing, wherein advertisers were charged based on the number of times a sponsored link was actually clicked. Companies have developed extensive search advertising strategies, based, for example, on how much to bid for keywords.

Social Media

Social media is playing an increasingly important brand communication role due its massive growth. Social media allows consumers to share text, images, audio, and video online with each other and—if they choose—with representatives from companies. Social media comes in many forms, but six key options are: (1) message boards and forums, (2) chat rooms, (3) blogs, (4) Facebook, (5) Twitter, and (6) YouTube.

The numbers associated with social media are truly staggering. In November 2010, nearly one in four page views in the United States took place on Facebook. One forecast projected that by 2014, roughly two-thirds of U.S. Internet users will be regular visitors to social media networks.53

Social media offers many benefits to marketers. It allows brands to establish a public voice and presence on the Web. It complements and reinforces other communication activities. It helps promote innovation and relevance for the brand. By permitting personal, independent expression, message boards, chat rooms, and blogs can create a sense of community and foster active engagement.

Some social networks, such as Sugar and Gawker, provide an easy means for consumers to learn from and express attitudes and opinions to others. They also permit feedback that can improve all aspects of a brand’s marketing program. Dr. Pepper has an enormous 8.5 million fan base on Facebook. Careful tracking and testing with Facebook users who state that they the “like” the brand has allowed the brand to fine-tune its marketing messages. With consumers increasingly avoiding surveys, many marketing researchers are excited about the potential of social networks to yield market insights.54

Social media clearly offers enormous opportunities for marketers to connect with consumers in ways that were not possible before. Although some marketers were uncertain as to whether they should engage in social media, many have come to realize that online conversations will occur whether they want them to or not, so the best strategy seems to be to determine how to best participate and be involved. Accordingly, many companies now have official Twitter handles and Facebook pages for their brands.

Different social media can accomplish different objectives. Landor’s Allen Adamson views the chief role of Twitter—with its 140 character text-based limit for posting—as an “early warning system” so marketers know exactly what is happening in the marketplace and how to respond at any one point in time. For example, when a customer tweeted about a bad customer experience with Zappos, because the company was monitoring social media, it was able to immediately send an explanation, apology, and coupon.55

Facebook, on the other hand, is more about long-term relationship building and can be used to engage consumers and delve more deeply into their interests and passions. As popular as Facebook is, it is not the only game in town. Special-interest community sites such as GoFISHn, with over 150,000 loyal anglers, and Dogster, with over 600,000 dog lovers, present even more focused targets.56

Some brands have fully embraced social media. Lego has always involved lead users and fans in its brand marketing activities, so it is no surprise it has thousands of YouTube videos and Flickr photos. Even top executives of some brands, such as Virgin’s Richard Branson and Zappos’s Tony Hsieh, weigh in with their comments. When companies choose to engage in social media, speed of response and the proper tone is critical.

There is no question that some consumers are choosing to become engaged with a brand at a deeper and broader level, and marketers must do everything they can to encourage them to do so. P&G invested heavily in 2010 to expand its Facebook presence with its brands. Fifteen of its brands quickly gained over 100,000 followers, and Pringles and Old Spice gained 9 million and 1.3 million, respectively. Its “Mean Girls Stink” antibullying Facebook app for Secret deodorant was downloaded more than 250,000 times.57

As exciting as these kinds of prospects are, marketers must also bear in mind that not everyone actively participates in social media. Only some of the consumers want to get involved with only some of the brands and, even then, only some of the time. Understanding how to best market a brand given such diversity in consumer backgrounds and interests is crucially important and will separate digital marketing winners and losers in the years to come.

Putting It All Together

Interactive marketing communications work well together. Attention-getting online ads and videos can drive consumers to a brand’s Web sites, where they can learn and experience more about the brand. Company-managed bulletin boards and blogs may then help create more engagement. Interactive marketing communications reinforces other forms of marketing communications as well.

Many experts maintain that a successful digitally based campaign for a brand often skillfully blends three different forms of media: paid, owned, and earned media. Paid media is all the various forms of more traditional advertising media described above, including TV and print. Owned media are those media channels the brand controls to some extent—Web sites, e-mails, social media, etc. Earned media are when consumers themselves communicate about the brand via social media, word-of-mouth, etc. It should be recognized that the lines sometimes blur, and communications can perform more than one function. For example, YouTube costs marketers to maintain, is under their control, but is also importantly social.

The interplay between the three forms of media is crucial. As one critic noted, “Paid media jump starts owned; owned sustains earned; and earned drives costs down and effectiveness up.”58 Procter & Gamble’s highly successful “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” starring ex-football player Isaiah Mustafa started with humorous tongue-in-cheek ads (paid media) that migrated online to YouTube, Facebook, and a brand microsite (owned media) before gaining heightened public attention via word-of-mouth, media reports, and social network interactions (earned media).

It is important to track all form of social media formally and informally. A number of firms have popped up to assist firms in this pursuit. For its Gatorade brand, PepsiCo actually created its own “Mission Control” where four full-time employees monitor social-media posts 24 hours a day. Any mention of Gatorade on Twitter, Facebook, or elsewhere is flagged, allowing the company to join conversations when needed and appropriate, such as when a Facebook poster incorrectly noted that Gatorade contains high-fructose corn syrup.59

Marketers have become more thoughtful about how to measure social media and classify interactive marketing success. The fact is, no matter how many they are, Facebook fans and Twitter followers will not matter if they are not engaged with the brand. Popular viral videos—like Burger King’s “Subservient Chicken”—will mean little if they don’t help to drive sales in some way.60

Events and Experiences

As important as online marketing is to brand management, events and experiences play an equally important role. Brand building in the virtual world must be complemented with brand building in the real or physical world. Events and experiences range from an extravagant multimillion dollar sponsorship of a major international event to a simple local in-store product demonstration or sampling program. What all these different kinds of events and experiences share is that, one way or another, the brand engages the consumers’ senses and imagination, changing brand knowledge in the process.