Advice the Best Organisations Give Us

The lessons and their implications

But we’re different! – organisational context

The advice in this chapter is based on a benchmarking exercise undertaken by the author, coupled with his own experience of working within a number of major organisations.

‘Example moves the world more than doctrine.’

HENRY MILLER

The study

The problems outlined in the previous chapter are significant and far reaching. Finding solutions you can trust and have confidence in, is itself difficult. The advice in this chapter is based on a benchmarking study undertaken by the author, coupled with his own experience of working within several major organisations across a number of industries.

The benchmarking questions were not directly related to project management but to ‘product development’. In a business context, a project is a project, regardless of whether it is technology based, for cultural change, complex change, or whatever. As the development and launching of new products and services touches almost every part of an organisation, projects in this field are an excellent medium for learning about complex, cross-functional projects and how organisations address them. If an organisation cannot develop new products and services efficiently, it is probable that it cannot tackle any other form of cross-functional project effectively either. The full set of questions is on the CD-ROM. The study had the following characteristics:

- It covered a wide range of industries.

- It was predominantly qualitative with only a few quantitative questions added to obtain such ‘hard data’ as were available. It was considered more important to find out how people worked rather than collect statistics. Even today, obtaining statistics which are truly comparable across different organisations and sectors is very difficult.

The objective was to ‘learn from the best’, hence the inclusion of a number of industries, both rich and poor, in the study:

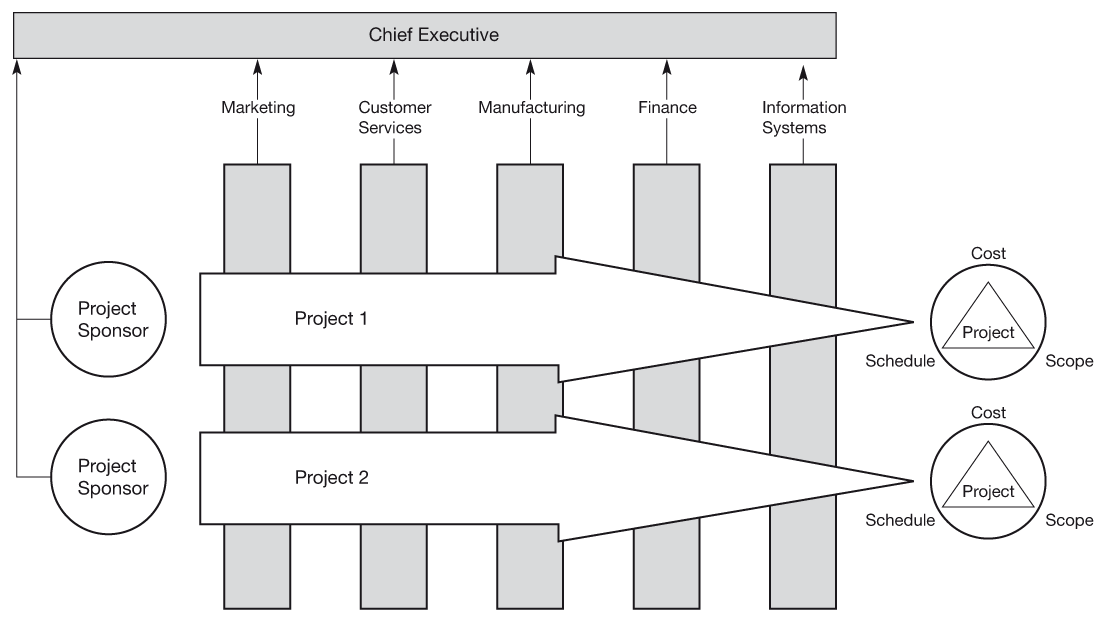

The organisations chosen for the study were those which had clearly demonstrated success in their own fields and markets. Despite the diverse industries, we found a marked similarity in approach taken by all those organisations interviewed. They are all using or currently implementing a ‘staged’, ‘cross-functional’ framework within which to manage their product development projects (Figure 2.1). The number of stages may differ from organisation to organisation, but all have the characteristic of investing a certain amount of the organisation’s resources to obtain more information across the full range of activities which impact a project and its outcome, namely:

- market;

- operational;

- technical;

- commercial and financial.

The additional finding was that some of the organisations did not confine their approach to product development only, but applied it to business change projects generally, i.e. to everything they did that created change in the organisation. In other words, they had a common business-led project framework for managing change generally.

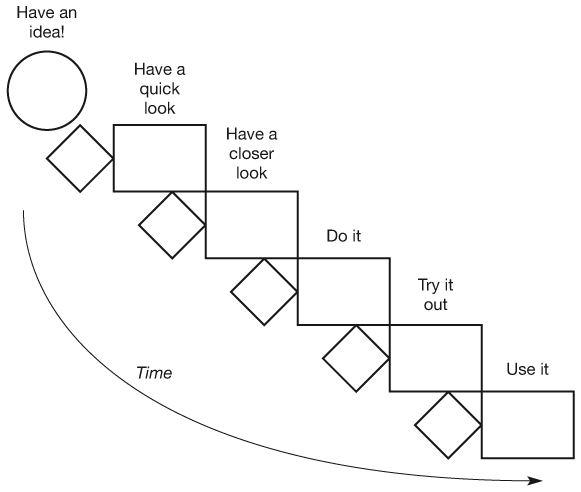

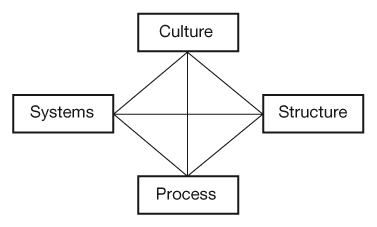

There, however, the similarities between organisations end as the individual culture and the nature of the different industries take over. Figure 2.2 illustrates that any process (including project management) sits within a context of culture, systems and organisation structure; alter any one and it will affect the others.

Figure 2.1 A typical staged project process framework

A staged approach to projects starts with a preliminary look at the objectives and possible solutions and results, via a more detailed investigation, development and trial, and the release of the outputs into the business’ operational environment. You should not start any stage without meeting the prescribed criteria at the preceding gate. This includes checks on strategic fit and ‘do-ability’ as well as financial considerations.

Figure 2.2 The organisational context for project management and other processes

No process sits in isolation. How you are organised, the systems you use to support the process and the prevailing culture of the organisation, all affect how well any process works.

This single observation means that although project management processes in many organisations may be similar in principle, the culture and behaviours which makes them work are different. Logically, if an already proven process appears to break down, the fault may lie outside the process itself in one of the other aspects of the organisation. One CEO told me, ‘We know our process is logical; if it isn’t working we look first at the people trying to make it work rather than at the process itself.’ This company had a well-established project management process in which it had a very high degree of confidence. However, it still maintained the good practice of continually improving its processes by promoting feedback and having quarterly performance reviews. Another organisation had a very effective gating process (see Chapter 3), which totally failed when a new management team took over the programme. This observation also means that a process which works fine in one organisation will not necessarily work in every organisation.

Also notable was that certain industries were excellent in particular aspects of managing projects as a result of the nature of their business. Often, they took this for granted. For example:

‘Concentrate on the early stages’ was a message which came across loud and clear, but it was the organisations that relied on bids or tenders for their business which really put the effort in up front as the effect of failure was immediately obvious – they lost business or won unprofitable business. In organisations where ‘bidding’ is not the rule, the effects of poor upfront work are not so immediately obvious and may take a long time to become apparent. Too long.

‘Manage risks’ was another message. The only company to tell me, unprompted, that it was excellent in risk management was in avionics, where the consequences of failure can be painfully obvious – aircraft fall out of the sky. Interestingly enough, the company does not claim to use very sophisticated risk-management techniques, but rather has designed its whole approach with a risk-management bias. It cites its staged process as a key part of this.

‘Measure everything you do.’ Organisations which need to keep a track of man hours in order to bill their customers (e.g. consultants, system development houses) also have the most comprehensive cost and resource planning and monitoring systems. These provide not only a view of each individual project, but also enable them to collate and summarise the current status for all their projects, giving them a quantum leap in management information which most other organisations do not have.

The lessons and their implications

The lessons are summarised below and are described more fully on the following pages. The quotations are taken from the study notes.

The first seven lessons apply throughout the life of a project:

| 1 | Make sure your projects are driven by benefits which support your strategy. |

| 2 | Use the same, simple and well-defined framework, with a staged approach, for all projects in all circumstances. |

| 3 | Address and revalidate the marketing, commercial, operational and technical viability of the project throughout its life. |

| 4 | Incorporate stakeholders into the project to understand their current and future needs. |

| 5 | Build excellence in project management techniques and controls across the organisation. |

| 6 | Break down functional boundaries by using cross-functional teams. |

| 7 | Use dedicated resources for each category of development and prioritise within each category. |

| The next three lessons apply to particular stages in the project: | |

| 8 | THE START Place high emphasis on the early stages of the project. |

| 9 | THE MIDDLE Build the business case into the company’s forward plan as soon as the project has been formally approved. |

| 10 | THE END Close the project formally to build a bridge to the future, to learn any lessons and to ensure a clean handover. |

1 Make sure your projects are driven by benefits which support your strategy

‘If you don’t know why you want to do a project, don’t do it!’

All the organisations were able to demonstrate explicitly how each project they undertook fitted their business strategy. The screening out of unwanted projects as soon as possible was key. At the start, there is usually insufficient information of a financial nature to make a decision regarding the viability of the project. However, strategic fit should be assessable from the beginning. Not surprisingly, those organisations which had clear strategies were able to screen more effectively than those which didn’t. Strategic fit was often assessed by using simple questions such as:

- Will this product ensure we maintain our leadership position?

- Will the results promote a long-term relationship with our customers?

The less clear the strategy, the more likely projects are to pass the initial screening: so there will be more projects competing for scarce resources resulting in the company losing focus and jeopardising its overall performance.

2 Use the same, simple and well-defined framework, with a staged approach, for all projects in all circumstances

‘Our usual process is our fast-track process.’

As discussed earlier, use of a staged framework was found to be well established. Rarely is it possible to plan a project in its entirety from start to finish; there are simply too many unknowns. By using defined project stages, it is possible to plan the next stage in detail, with the remaining stages planned in summary. As you progress through the project from stage to stage, your end-point becomes clearer and your confidence in delivery increases. It was apparent that organisations were striving to make their project frameworks as simple as possible, minimising the number of stages and cutting down the weight of supporting documentation. Further, the same generic stages were used for all types of project (e.g. for a new plastic bottle and for a new manufacturing line; for a project of £1,000 cost to one of £10m cost).

This makes the use and understanding of the framework very much easier and avoids the need for learning different frameworks and processes for different types of project. This is particularly important for those sponsoring projects or who are infrequently involved in projects. By having one basic framework they are able to understand their role within it and do not have to learn a new language and approach for each situation.

What differs is the work content of each project, the level of activity, the nature of the activity, the degree of risk, the resources required, and the stakeholders and decision makers needed.

A common criticism is that a staged approach slows projects down. This was explored in the interviews and found not to be the case. In contrast, a staged approach was believed to speed up desirable projects. One relevant point is the nature of the gates. Some organisations used them as ‘entry’ points to the next stage rather than the more traditionally accepted ‘exit’ point from a previous stage. This simple principle has the effect of allowing a stage to start before the previous stage has been completed. In this way stages can overlap without increasing the risk to the business, provided the gate criteria are met.

The existence of so-called ‘fast-track’ processes to speed up projects was also investigated. In all cases, the organisations said that their ‘usual process’ was the fast track. Doing anything else, such as skipping stages or going ahead without fully preparing for each stage, increases the risk of the project failing. The message from the more mature organisations was that ‘going fast’ by missing essential work actually slowed the project down; the amount of rework required was nearly always much greater than the effort saved. When people talk of fast tracking, what they usually mean is raising the priority of a project so it is not slowed down by lack of resources.

3 Address and revalidate the marketing, commercial, operational and technical viability of the project throughout its life

‘We are very good at slamming on the brakes very quickly if we see we cannot achieve our goals.’

All the organisations address all aspects throughout the life of a project. No single facet is allowed to proceed at a greater pace than the others as, for example, there is little point in:

- having an excellent technological product which has no adequate market rationale relating to it and cannot be economically produced;

- developing a superb new staff appraisal system if there are no processes to administer it and make it happen.

As the project moves forward, the level of knowledge increases and hence the level of risk should decrease. The only exception is where there is a particularly large area of risk and this work may be brought forward in order to understand the problems and manage the consequences as part of a planned risk-management strategy.

Coupled with this, the ability of organisations to stop (terminate) projects was seen to be important. Some expressed themselves to be experts at this. A problem in any one aspect of the project (e.g. market, operations, technology, finance) can lead to termination. For example, one company, which has a product leadership strategy, killed a new product just prior to launch as a competitor had just released a superior product. It was better to abort the launch and work on the next generation product, than to proceed with releasing a new product which could be seen, by the market, as inferior. If the company had done so, its strategy of product leadership would have been compromised, with the technical press rubbing their hands with glee!

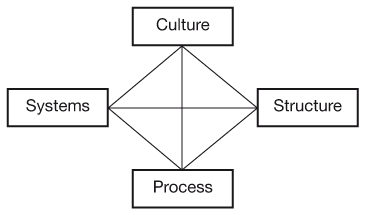

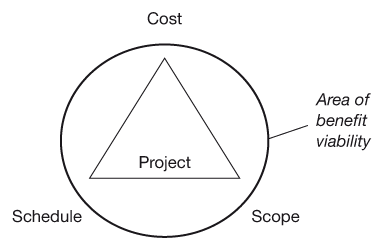

Naturally, the gates prior to each stage are the key checkpoints for revalidating a project. The best organisations also monitor the validity of the project between gates and are prepared to stop it if their business objectives are not likely to be met. At all times, the project schedule, cost, scope and benefits must be kept in balance (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 The project balance

A project comprises a defined scope (deliverables), to be delivered in an agreed timescale, at an agreed cost. These must be combined in such a way to ensure that the project is always viable and will realise the expected benefits. If any one of these falls outside the area of benefit viability, the others should be changed to bring the project back on target. If this cannot be done the project should be terminated.

4 Incorporate stakeholders into the project to understand their current and future needs

‘The front line customer interface has been and is our primary focus.’

The involvement of stakeholders, such as users and customers, in projects was seen to add considerable value in all stages of a project. Usually, the earlier they are involved, the better the result.

The more ‘consultancy-oriented’ organisations must, by the nature of the work they do, talk to customers to ascertain their needs. But even these organisations said they often misinterpreted the real needs of the customer despite great efforts to avoid this. Where project teams are more removed from their users or customers, there is even greater scope for error.

Many innovative ways have been used to obtain this involvement including:

- focus groups;

- facilitated workshops;

- early prototyping;

- simulations.

Involving the stakeholders is a powerful mover for change, while ignoring them can lead to failure. When viewed from a stakeholder’s perspective, your project may be just one more that the stakeholder has to cope with as well as fulfilling his or her usual duties; it may even appear irrelevant or regressive. If the stakeholders’ consent is required to make things happen, you ignore them at your peril!

5 Build excellence in project management techniques and controls across the organisation

‘Never see project management as an overhead.’

All the organisations I interviewed see good project management techniques and controls as prerequisites to effecting change. Project management skills are still most obvious in the engineering-based organisations, particularly those which have a project/line matrix management structure. However, other organisations had taken, or were taking, active steps to improve this discipline across all parts of the business.

There must be project management guidance, training and support for all staff related to projects, including senior managers who sponsor projects or make project-related decisions. Core control techniques identified in the organisations included planning and managing risk, issues, scope changes, schedule, costs and reviews.

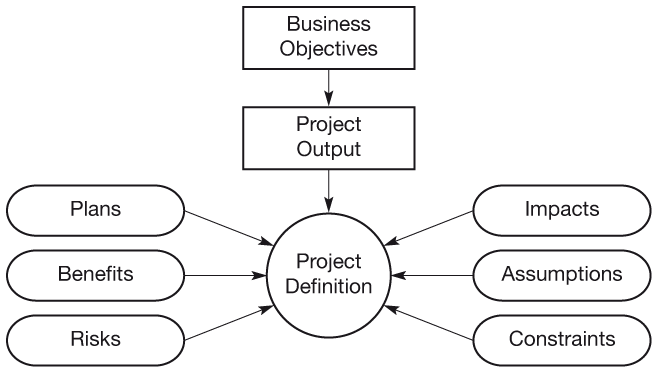

Planning as a discipline is seen as essential. If you have no definition of the project and no plan, you are unlikely to be successful. It is virtually impossible to communicate your intentions to the project team and stakeholders. Further, if there is no plan, phrases such as ‘early’, ‘late’ and ‘within budget’ have no real meaning. Planning should be seen to be holistic, encompassing schedule, cost, scope and benefits refined in light of resource constraints and business risk (Figure 2.4).

Risk was particularly mentioned: using a staged approach is itself a risk-management technique with the gates acting as formal review points where risk is put in the context of the business benefits and cost of delivery. Projects are risky and it is essential to analyse the project, determine which are the inherently risky parts and take action to reduce, avoid or, in some cases, insure against those risks.

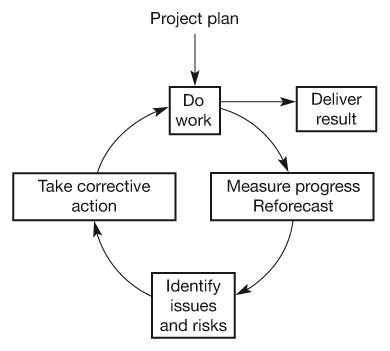

Despite good planning things will not always go smoothly. Unforeseen issues do arise which, if not resolved, threaten the success of the project. Monitoring and forecasting against the agreed plan is a discipline which ensures events do not take those involved in the project by surprise. This is illustrated by the ‘project control cycle’ in Figure 2.5. The appropriate frequency for the cycle depends on the project, its stage of development and inherent risk. Monthly is considered the most appropriate by many of the organisations although in certain circumstances this is increased to weekly.

Figure 2.4 Planning

Planning should be seen to be holistic, encompassing schedule, cost, scope and benefits refined in light of resource constraints and business risk.

Figure 2.5 Project control cycle

The project control cycle comprises doing the work as set out in your plan, measuring progress against that plan, identifying any risks, opportunities or issues and taking corrective action to keep the project on track. From time to time, results, in the form of deliverables, are generated. (Copyright © PA Consulting Group, London)

Such monitoring should focus more on future benefits and performance than on what has actually been completed. Completion of activities is evidence of progress but not sufficient to predict that milestones will continue to be met. The project manager should be continually checking to see that the plan is still fit for its purpose and likely to realise the business benefits on time. Here, the future is more important than the past.

It is a sad fact that many projects are late, or never reach completion. One of the reasons for this is ‘scope creep’. More and more ideas are incorporated into the project scope resulting in higher costs and late delivery. Controlling change is critical to ensuring that benefits are achieved and that the project is not derailed by ‘good ideas’ or ‘good intentions’. Changes are a fact of life and cannot be avoided. Good planning and a staged approach reduce the potential for major change but cannot prevent it. Changes, even beneficial ones, must be controlled to ensure that only those which enable the project benefits to be realised are accepted. Contracting industries are particularly good at controlling change as their income is directly derived from projects – doing ‘that bit more’ without checking its impact on their contractual obligations is not good business. Why should it be any less so when dealing with ‘internal projects?’

6 Break down functional boundaries by using cross-functional teams

‘No one in this company can consider themselves outside the scope and influence of projects.’

The need for many projects to draw on people from a range of functions means that a cross-functional team approach is essential. Running ‘projects’ in functional parts with coordination between them always slows down progress, produces less satisfactory results and increases the likelihood of errors. All the organisations in the study recognise this and have working practices which encourage lateral cooperation and communication rather than hierarchical (Figure 2.6). In some cases this goes as far as removing staff from their own departmental locations and grouping them in project team work spaces. In others, departments which frequently work together are located as close as practical in the company’s premises. Generally, the closer people work, the better they perform. Although this is not always practical, closeness can be compensated for by frequent meetings and good communication.

Cross-functional team working, however, is not the only facet. It was also seen that decision making has to be on a cross-functional basis. Decision making and the associated processes was an area where some of the organisations were less than satisfied with their current position. Either decision makers took too narrow a view or insufficient information was available.

Another requirement of cross-functional working is to ensure that both corporate and individual objectives are not placed in conflict. For example, one company found that team members on the same project received different levels of bonuses merely because they belonged to different departments.

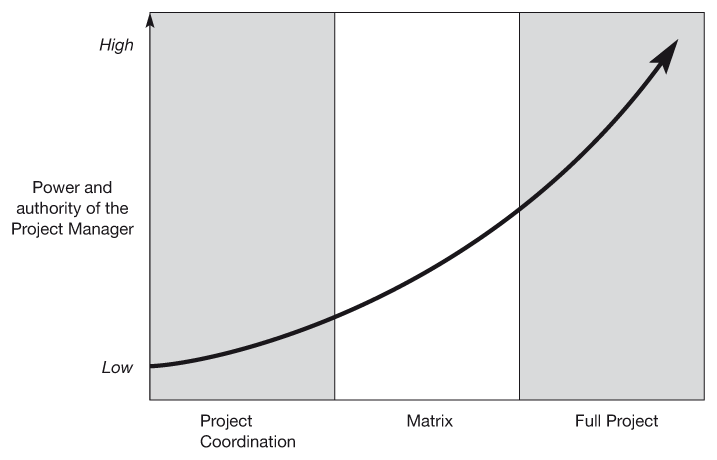

The more functionally structured an organisation is, the more difficult it is to implement effective project management. This is because project management, by its nature, crosses functional boundaries. To make projects succeed, the balance of power usually needs to be tipped toward the project and away from line management (see Figure 2.11). For a ‘traditional’, functionally led company, this is often a sacrifice its leaders refuse to make … at the expense of overall business performance.

THE FULL PROJECT ENVIRONMENT

Lesson 5 says use ‘good project management tools and techniques’, BUT it is only one of ten findings which provide the full environment for projects to work. Is this why some organisations say ‘we do project management, but it doesn’t work for us’?

7 Use dedicated resources for each category of development and prioritise within each category

‘We thought long and hard about ring fencing (dedicating) resources and decided, for us, it was the best way to minimise internal conflict.’

The management and allocation of resources was acknowledged by many organisations to be a problem. There is often continual competition for scarce resources between projects. One company said that at one time this had reached such a level that it was proving destructive. The impact was often that too many projects were started and few were finished.

I discovered that this problem was dealt with in two separate ways, both of which have their merits.

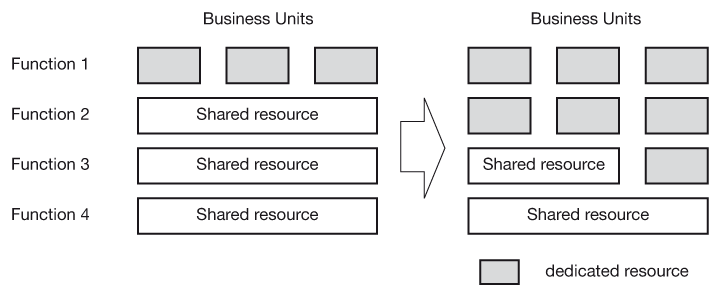

The first (Figure 2.7) is to apply dedicated (separate) resources for each category of project (say, aligned around a business unit) and take this principle as deep as possible into the organisation. In this way the potential conflicts are limited and the decisions and choices are more localised. In fact, the more separate and dedicated you make your resources, the more local your decision making can be, providing a project only needs to draw resource from that single pool. The down side of such an approach is that you will have to continually reorganise and resize your resource pools to meet demand. In a fast-moving industry this can mean you may have the right number of people but they may be deployed in the wrong places. It can lead to continual, expensive reorganisations. Most traditional, functionally based organisations follow this approach.

Figure 2.7 Apply dedicated resource to each project portfolio (e.g. by strategic business unit, market sector) as deeply as possible

Some organisations, as a result of their organisational structure, share most of their resources across a number of categories. This allows them to deploy the most appropriate people to any project regardless of where they are in the organisation. It also ensures that there is little duplication of functions within the organisation. Other organisations separate their resources to a greater extent and confine them to working on a single business unit’s projects. This allows quicker and more localised resource management but can lead to duplication of functional capabilities.

The second extreme is to have all staff in a single pool (shared) and to use effective matrix management support tools for resource allocation and forecasting (Figure 2.8). This method was adopted by the consulting and engineering organisations. In one case a person may work on up to ten projects in a week and there may be 300 projects in progress at any one time. It is very effective, conceptually simple and totally flexible. Major reorganisations are less frequent but it is also the most difficult to implement in a company which has a strong functional management bias.

In practice, a hybrid between the two extremes will provide the simplicity of purely functionally based organisations with the flexibility of full matrix-managed organisations. The implication is, however, that the resource management and accounting systems must be able to view the company in a consistent way from both perspectives.

Figure 2.8 Resources from all functions are applied anywhere, to best effect

In this model anyone from any function can work on any project. It is the most flexible way of organising but, without good control systems, is the most complex.

8 Place high emphasis on the early stages of the project

‘Skipping the first stage is a driver for failure.’

All organisations see the early stages of a project as fundamental to success. Some could not stress this enough. High emphasis for some meant that between 30 and 50 per cent of the project life is spent on the investigative stages before any final deliverable is physically built. One American company had research data explicitly stating that this emphasis significantly decreased time to completion. Good investigative work means clearer objectives and plans; work spent on this is rarely wasted. Decisions taken in the early stages of a project have a far reaching effect and set the tone for the remainder of the project. In the early stages, creative solutions can slash delivery times in half and cut costs dramatically. However, once development is under way, it is rarely possible to effect savings of anything other than a few per cent. Good upfront work also reduces the likelihood of change later, as most changes on projects are actually reactive to misunderstandings over requirements and approach rather than proactive decisions to change the project for the better. The further you are into the project the more costly change becomes.

Despite this, there is often pressure, for what appear to be all the right commercial reasons, to skip the investigative stages and ‘get on with the real work’ as soon as possible (so-called fast tracking, see Lesson 2). Two organisations interviewed had found through bitter experience that you can’t go any faster by missing out essential work. One told me that ‘skipping the investigative stages led to failure’; the other: ‘Whenever we’ve tried to leave a bit out for the sake of speed, we’ve always failed and had to do more extensive rework later which cost us far in excess of anything we might have saved.’

9 Build the business case into the organisation’s forward plan as soon as the project has been formally approved

‘Once it is authorised, pin it down!’

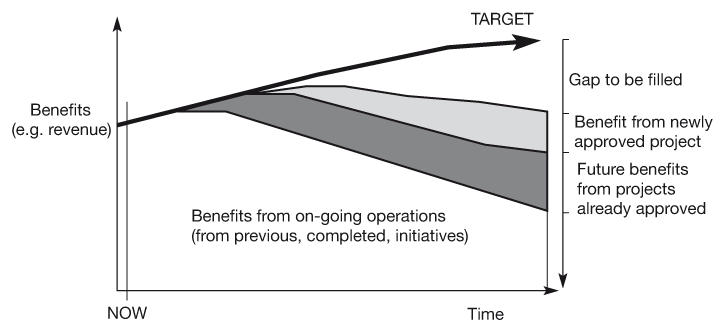

Projects are the vehicles for implementing future strategic change and revenue generation for a company. The best organisations are always sure that the projects they are undertaking will produce what they need and that they fit the company’s wider objectives. In all cases, organisations had far more proposals for projects than they could handle. It is, therefore, essential to know what future resources (cash, manpower, etc.) have already been committed and what benefits (revenues, cost savings, etc.) are expected. Unless this is done the ‘gap’ between where the company is now and where it wants to be is not known and so the choice of projects to fill the gap is made more difficult (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9 Build the project into your business plan as soon as it is authorised

The figure shows the revenue which will be generated by the organisation if no new projects are started. It then shows the revenue which will be generated by projects which are currently in progress. The gap between the sum of these and the target revenue needs to be filled. This can be by starting off new projects which will cause this to be generated or/and by starting initiatives in the line which will deliver the extra revenue to fill the gap.

Organisations handle this by having set points in the project life cycle at which cost and benefit streams are built into the business plan usually at the Development Gate (see Figures 3.6 and 3.7).

Clearly, financial planning and resource systems must be able to be updated at any time as projects do not recognise fiscal periods as relevant to start or finish dates. Also, any such project systems must be seen as a part of the business and not be seen as an ‘add-on’ outside the usual pattern of planning, forecasting and accounting.

10 Close the project formally to build a bridge to the future, to learn any lessons and to ensure a clean handover

‘We close projects quickly to prevent any left-over budget from being wasted.’

Closing projects formally is for some organisations essential. For example, low margin organisations must close the project accounts down to ensure that no more time is spent working on projects which are finished, no matter how interesting! Their tight profit margins simply won’t allow this luxury. Similarly, component products in an aircraft can be in service long after the project team has dispersed or even well after some team members have retired! Not to have full records (resurrection documents) on these critical components for times of need is unthinkable.

All the organisations interviewed either have a formal closure procedure or were actively implementing one. This usually takes the form of a closure report which highlights any outstanding issues, ensures explicit handover of accountabilities and makes it clear to those who need to know that the project is finished.

Another key reason given for formal closure was that it provides an opportunity for learning lessons and improving the processes and workings of the company. One company left ‘closure’ out of its process in the original design, but soon realised it was vital and added it in. It simply found that if it did not close projects, the list of projects it was doing was just growing by the day.

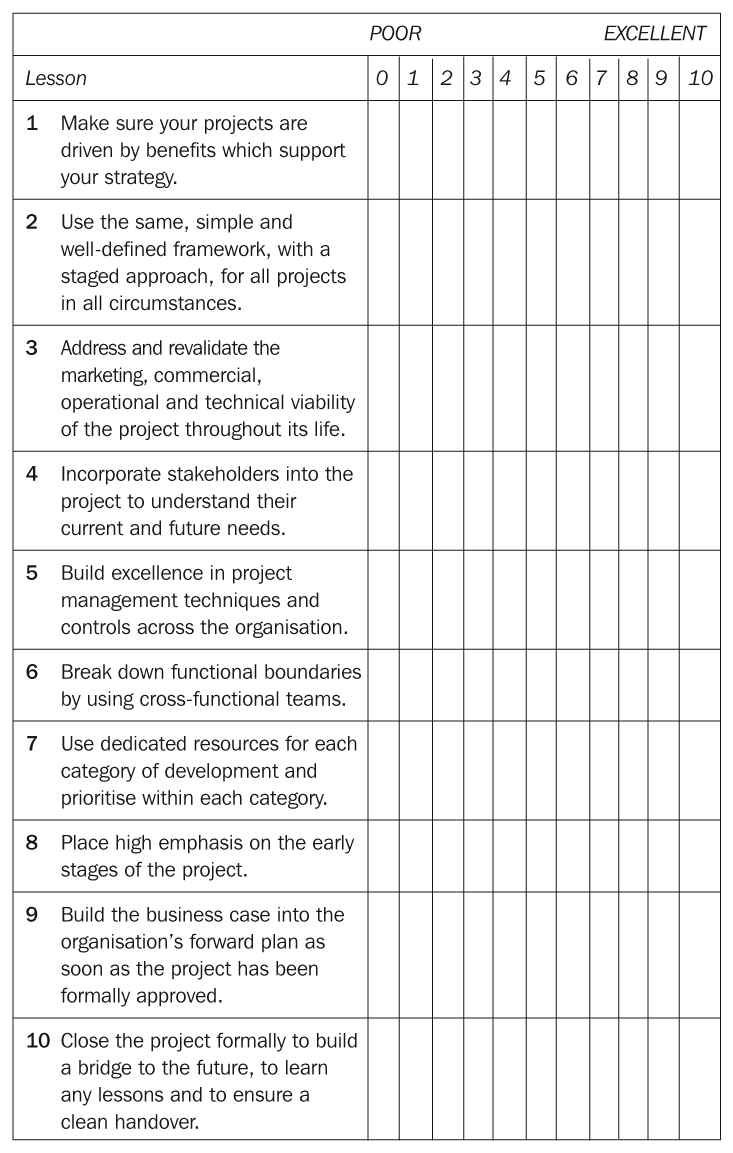

2.1 REVIEW OF THE TEN LESSONS

- As a management team for the business, review the ten lessons given in this chapter and ask yourself how well you apply them in your organisation at present. Agree a mark out of 10 and mark the relevant column in the table on p. 33 with an ‘X.’

10 = we currently apply this lesson fully across our organisation and can demonstrate this with ease.

0 = this is not applied at all. - Ask the project managers of, say, five of your projects to answer the same questions. Plot their answers with ‘P’.

- Ask the line managers of a number of your functions to answer the same questions. Plot their answers with ‘L’.

- Discuss, as a management team, the responses. Compare the answers you receive from the different stakeholder groups. Are there differences? If so, why do you think this is? Which lessons are not being applied? Why not?

- What do you propose to do about this?

But we’re different! – organisational context

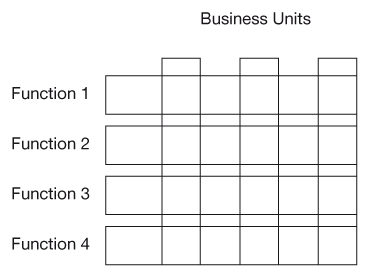

Project processes only work if they are supported by compatible accountabilities, culture and systems (Figure 2.10). The previous sections in this chapter described how many organisations use or are moving toward a staged project framework, but that the environments in which they operate are entirely different. So, when you hear the plaintive cry of ‘this won’t work here, we’re different!’, you can confidently answer ‘yes, we are different but we can make it work if we really want to.’

The following sections describe some of the wide range of approaches taken by different organisations.

Figure 2.10 The organisational context for project management and other processes

Ensure all your bases are covered. Culture sets out how we behave toward each other, top to bottom and side to side. Structure sets the accountabilities and relationships. Process provides consistency where consistency adds value. Systems make what we do easier, quicker, more reliable and cheaper. Change any one of these and it will impact the others.

Structure and accountabilities

Organisation structures vary from pure project to pure functional; this impacts the ease of cross-functional working and project management. Figure 2.11 shows the range of organisation shapes and the effect they tend to have on project management. In heavily functionally driven organisations, project managers are generally very weak, disempowered and at the mercy of the functional heads of department. They are often called ‘project coordinators’, which is very apt. In full project organisations, the project managers have greater power and influence over and above heads of department. In the middle is matrix management. This is a much maligned structure but one that can be very effective in organisations which require a relatively stable functional structure but still need to have the advantages of a cross-functional project approach. It has often been said ‘matrices don’t work, they just confuse’. Yes, that’s probably true if they are attempted in an environment with no suitable controls and incompatible line and project accountabilities and processes. Generally, those organisations which have moved the balance of power away from the line and towards the project, have found project management and cross-functional working more effective and reap greater rewards.

The acceptance of clear definitions of roles, accountabilities and relationships for the key players are most apparent with those organisations which are comfortable with their processes. Further, the separation of ‘role’ from job description is seen as crucial to maintaining simplicity, as in cross-functional, project environments, the role a person takes (e.g. as project sponsor or project manager) is more important than the job title or position in the functional hierarchy.

Figure 2.11 Project organisations

Organisations can structure themselves with differing emphasis on line and project management authority. When the most power is invested in line management, project managers are reduced to a ‘coordination’ role. In full project structures, the project manager has greater power than the line manager.

Some organisations set up cross-functional groups to undertake particular tasks on an on-going basis. The most obvious are those groups which undertake the screening of proposals prior to entry to the project process. In this way the structures created match the process (rather than leading or following the process). This must also apply to any review or decision-making bodies which are created. The one most commonly found to be adrift is that relating to financial authorisations. Many organisations have almost parallel financial processes shadowing their project processes, demanding similar but different justifications and descriptions of projects. This is usually found where finance functions have disproportionate power and act as controllers rather than in an assurance or business partner mode. The better organisations ensured that there was little divergence between decisions required for finance and those relating to strategy. They make certain that financial expertise is built into the project in the same way as any other discipline, with finance people being included on the project team.

Projects are ‘temporary’ and cease to exist once completed. Clear accountability for on-going management of the outputs in the line ensures that the right people are involved in the project and that the handover is clean and explicit. Career progression and continuity of employment for people involved in projects must be a top consideration. Projects are about change and about the future of your organisation. Good organisations ensure that the people who create these changes are retained and that projects are not seen as career limiting and the fast track to redundancy. You need your best people to create your future organisation, not the ‘leftovers’ from running yesterday’s organisation.

A large, global company was having difficulty ensuring its people worked cooperatively across department and functional boundaries (typical silo behaviour). This had been raised on a number of occasions at senior team level. One day, the chief executive officer told me he had fixed the problem. ‘How?’ I asked. ‘I’ve put all problem functions under Andy,’ he replied. ‘How does an extra management tier and the creation of an even bigger silo solve the problem?’ I asked. There was silence lasting for a full minute. ‘Well, that’s what I’ve done,’ he eventually said.

Clearly, this chief executive officer had not fully understood the problem and was merely offloading it onto someone else. Further, he was using a structural solution in an attempt to solve a cultural problem. (You will recall Figure 2.10.)

Culture

Culture is probably the least reproducible facet of an organisation and the most intangible. It does, however, have a very significant impact on how projects are carried out and how project management is implemented.

For example, the corporate attitude to risk and the way an organisation behaves if high-risk projects have to be stopped will have far reaching effects on the quality of the outputs produced. In avionics the ‘least risk’ approach is generally preferred to the ‘least cost’ despite being within an industry in which accepting the lowest tender is a primary driver.

One company interviewed explicitly strives to make its own products obsolete as it clearly sees itself as a product leader. It is forever initiating new projects to build better products quicker and more frequently than the competition. This same company focuses its rewards on teams, not individuals, and takes great care to ensure its performance measurement systems avoid internal conflict. Another company admitted that its bonus schemes were all based on functional performance and not team performance despite 60 per cent of the staff working cross-functionally. An example was given of a staff member who received no bonus for his year’s work, but all his colleagues on the the same project (in a different department!) had large bonuses. This was not seen as ‘fair’, and was the result of basing bonuses on something that could be counted easily rather than on something that actually counted!

Another company has no bonus scheme below senior management level but provides ‘Well Done’ awards (financial) for individuals whom they consider merit them. These are given almost immediately after the event which prompted the award and are well appreciated. This same company also has 100 per cent employee ownership and salesmen who are not commissioned.

Most of the organisations interviewed encouraged direct access to decision makers as it improves the quality of decisions. Project roles, rather than ‘job descriptions’, promote this. Functional hierarchies tend to have a greater ‘power distance’ and decision makers become remote from the effects of their actions or the issues involved.

As a paradox, those organisations which have the most comprehensive control systems (project accounting, resource management, time sheeting, etc.) are able to delegate decision making lower in the organisation. Senior management does not lose sight of what is happening and always knows who is accountable.

A major producer of project scheduling software confided in me that when it came to managing its own internal business projects, all the good practice and advice the company advocated as essential to its customers was ignored. The culture of the company’s management simply does not fit the product it sells. Organisations can be very successful without any rational approach to business projects but are unlikely to remain successful for long.

2.2 WHAT HAPPENS TO PROJECT MANAGERS IN YOUR ORGANISATION WHEN THE PROJECT IS FINISHED?

| (a) | They are kept on the payroll and assigned to a manager for ‘pay and rations’ until a new project or suitable alternative work is found. |

| (b) | They are put on a redeployment list and then made redundant if no suitable opening is found for them within x months. |

| (c) | They leave the organisation straightaway if no suitable opening is found for them. |

| (d) | They leave the organisation. |

| (e) | I don’t have this problem as they are all contracted in when needed. |

If you answered (b) to (d) you are probably very functionally driven and projects tend to be difficult to undertake.

If you answered (e) you may be in a very fortunate position to be able to source such key people OR you are in the same situation as (b) to (d).

If you answered (a) you are probably in a good position to reap the rewards of project working or are already doing so!

Debate with your colleagues: what motivates your staff to work on projects?

If you answered (b) to (d), do you really expect to have your best people volunteering to work on projects?

Systems and tools

A number of organisations stated that the accounting systems must serve to integrate process, project and line management. Projects must not be seen as an ‘add-on’.

Resource management and allocation was found to be a problem for many organisations. Those which found least difficulty centrally managed their entire resource across all their departments so that the departments and the projects used the same core system; only the reporting emphasis was different.

Other organisations had developed systems to cope with what they saw as their particular needs; for example, risk management or action tracking.

The American organisations had acquired the practice of constantly validating their processes and systems through benchmarking.

Conclusion

The benchmarking study confirmed that:

- The staged framework is widely used for business change projects and is delivering better value than more traditional functionally based processes. This is discussed further in Part Two of the book.

- A cross-functional, project management-based approach is essential. This is discussed further in Part Four of the book.

What is apparent is that the infrastructure which makes projects work varies considerably, in particular the level of information that decision makers have to support them. For example, it is usually relatively easy to decide if a project in isolation is viable or not. However, if you are to decide which of a number of projects should go ahead based on relative benefits, answers to the following questions are needed:

- What overall business objectives is the project driving toward?

- On what other projects does this project depend?

- What other projects depend on this project?

- When will we have the capacity to undertake the project (in terms of people and other resources)?

- Can the business accept this change together with all the other changes being imposed? If so, when?

- Do we have enough cash to carry out the project?

- After what length of time will the project cease to be viable?

- How big is the overall risk of the full project portfolio with/without this project?

The challenge lies in having processes, systems, accountabilities and a culture which address these, both at a working level and at the decision-making level. If this is not addressed it will result in:

- the wrong projects being undertaken;

- late delivery;

- failure to realise the expected benefits.

This will be in spite of having excellent processes and tools at an individual project level. These questions are addressed in Part Three of this book.

In one company, it was not unusual to find directors reporting to graduates on projects. The directors are on the project teams to add their particular knowledge and skills and not to lead the project. This company saw nothing strange about this arrangement. The most appropriate people were being used in the most appropriate way.

ENEMIES WITHIN

Running a project is difficult enough, but we often make it more arduous than it need be by creating problems for ourselves. Here are a few examples:

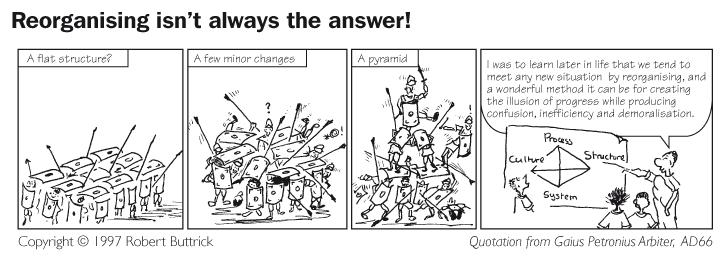

Reorganising – either the company or a part of it. Tinkering with your structure is usually NOT the solution to your problems, it just confuses people. The Romans realised this 2,000 years ago (see cartoon). If you are a senior executive, however, this is a great way to hide non-delivery!

Functional thinking – not taking the helicopter, the organisation-wide view. This often happens when executives’ or individuals’ bonuses are based on targets which are at odds with the organisation’s needs, e.g. sales bonus rewarded on revenue, regardless of profit or contribution.

Having too many rules – the more rules you have, the more sinners you create and the less happy your people become. Have you ever met a happy bureaucrat?

Disappearing and changing sponsors – without a sponsor there should be no project. Continual changing of the ‘driver’ will cause you to lose focus and forget WHY you are undertaking the project. Consider terminating such a project to see who really wants it!

Ignoring the risks – risks don’t go away, so acknowledge them and manage them. If I said that a certain aeroplane is likely to crash, would you fly on it? And yet, every day executives approve projects when a simple risk analysis shows they are highly likely to fail.

Dash in and get on with it! – if a project is that important, you haven’t the time NOT to plan your way ahead. High activity levels do not necessarily mean action or progress.

Analysis paralysis – you need to investigate, but only enough to gain the confidence to move on. This is the opposite to dash in and ignore the risks. It is also a ploy used to delay projects: ‘… I haven’t quite enough information to make a decision, just do some more study work.’

Untested assumptions – all assumptions are risks; treat them as such.

Forgetting what the project is for – if this happens, terminate the project. If it is that useful, someone will scream and remember why it is being done.

Executive’s ‘pet projects’ – have no exceptions. If an executive’s idea is really so good, it should stand up to the scrutiny that all the others go through. He or she may have a helicopter view, but might also have their head in the clouds.