The Project Framework: An Overview of its Gates and Stages

Projects as vehicles of change

Internal and customer-facing projects

How can I apply the framework?

Project management is still seen as a specialist discipline requiring special people who are difficult to find and to retain. While this is to a certain extent true, a scarcity of ‘project managers’ should not be a barrier to any organisation starting to develop a ‘projects’ approach to managing its own future.

‘The Golden Rule is that there is no golden rule.’

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

Projects as vehicles of change

‘Projects’ are rapidly becoming the way organisations should manage change and this applies not only to traditional activities such as large construction projects, but also to any change initiative aimed at putting a part of your business strategy into action. Projects, in the modern sense, are strategic management tools and you ignore the newly reborn discipline of enterprise-wide project management at your peril. It is fast becoming a core competence which many organisations require their employees and leaders to have. It is no longer the preserve of specialists and the engineering sector, but an activity for everyone. The problem is that most people simply do not have the right skills. Project management is still seen as a specialist discipline requiring special people who are difficult to find and to retain. While this is to a certain extent true, a scarcity of ‘project managers’ should not be a barrier to any organisation starting to develop a ‘projects’ approach to managing its future. Project management is simply applied common sense. All organisations say that their most important asset is their people (although the shareholders may be more interested in profit), but no organisation, however excellent, has a monopoly on ‘good people’; they are simply much better at getting ‘ordinary’ people to perform in an extraordinary way and their few ‘extraordinary’ people to perform beyond expectations. These organisations provide an environment which enables this to happen. Add to this a few, well-chosen project experts and you have a sound foundation for generating successful projects. Well-managed projects will enable you to react and adapt speedily to meet the challenges of your competitive environment, ensuring you drive toward an attainable, visible, corporate goal.

Most organisations are never short of good ideas for improvement and your own is probably no exception. Ideas can come from anywhere within the organisation or even outside it: from competitors, customers or suppliers. However, deciding which of all these good ideas you should actually spend time and money on is not easy. You must take care in choosing which projects you do, as:

- you probably don’t have enough money, manpower, or management energy to pursue all of your ideas;

- undertaking projects which you cannot easily reconcile with your organisation’s strategy will, almost certainly, create internal conflicts between projects, confuse the direction of the business and, ultimately, reduce the return on your company’s investment.

You should consider for selection only those projects which:

- have a firm root in your strategy (see p. 17).

- will realise real benefits;

- meet defined business needs;

- are derived from gaps identified in business plans;

Having created a shortlist of ‘possible projects’ it is important you work on them in the right order, recognising interdependencies, sharing scarce resources and bringing the benefits forward whenever possible.

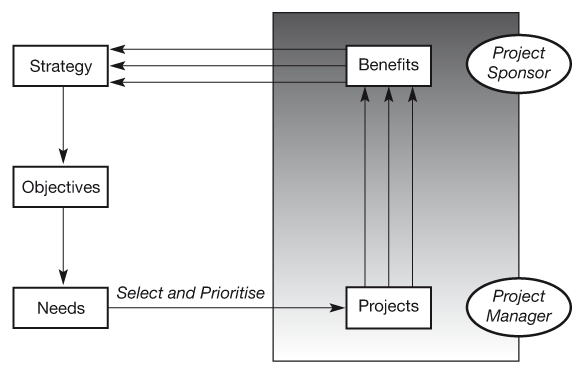

Figure 3.1 shows this in a diagram. Selecting the right projects will help you achieve your business objectives by realising benefits which support your strategy. Two key roles are associated with projects:

Figure 3.1 Select the right projects to support your strategy

Selecting the right projects will help you achieve your objectives by realising benefits which support your strategy.

(Copyright © PA Consulting Group, London. Adapted with kind permission)

The project manager is the person who manages the project on a day-today basis, ensuring that its deliverables are presented on time, at the right quality and to budget.

A simple illustration of these key project roles is that you may want to build an extension to your house that will give you a fully equipped den and/or home office. You want the benefits that will accrue. You and your family do not want all the dust, debris and inconvenience that construction will entail, but you accept this is the price (together with the monetary cost) you are willing to pay in order to obtain the benefits you seek. By the same token, the architect is more interested in designing and seeing constructed an elegant and appropriate solution that will meet your needs. As project manager, he/she is not fundamentally interested in the benefits you seek, but rather in the benefits received for carrying out the work (the fee). He/she must, however, understand your needs fully so that an appropriate solution can be delivered. In a good partnership, sponsorship and management are mutually compatible. Thus:

- the project sponsor is ‘benefits focused’;

- the project manager is ‘action and delivery focused.’

The framework for managing business-led projects is aimed at making the results of projects more predictable by:

- being benefits focused;

- building in quality;

- managing risks and exposure;

- exploiting the skill base of your organisation.

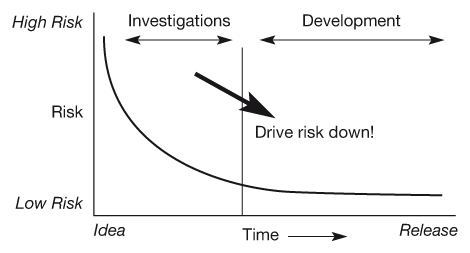

As a project proceeds over time, the amount of money invested in it increases. If none of this money is spent on reducing the risks associated with the project then it is poorly spent. Your objective is to ensure that risks are driven down as the project moves from being an idea to becoming a reality (see also pp. 18, 29).

Figure 3.2 demonstrates this. The investigative stages are crucial and you should hold back any development work until your investigations show you know what you are doing and have proved that the risks are acceptable.

Figure 3.2 Managing the risk

The investigative stages are crucial and you should hold back any development work until your investigations show you know what you are doing and have proved that the risks are acceptable.

You do this by using a staged approach where each stage serves as a launch pad for the subsequent stage. In this book I have used five stages, but other models are equally acceptable if they suit the environment and culture of your organisation.

Internal and customer-facing projects

Regardless of the organisational context, projects may be undertaken:

- Internally, to fulfil a need within an organisation, where the organisation undertakes a project for itself in order to achieve its business objectives and realise certain benefits. For example, a manufacturer may wish to build a new production plant to produce certain product lines efficiently.

- For customers, where an organisation (or supplier) undertakes a project, for payment. For example a civil engineering contractor would undertake a project for the construction of a bridge, but may have no interest in the bridge once it is handed over.

There are primarily two type of organisation commonly engaged on projects:

- Promoting organisations, which identify a business, strategic or political need, translate this into a set of objectives and, through project management, produce the outputs and changes to ensure those objectives are met. A promoting organisation may let out part of the project to a contracting organisation or supplier.

- Contracting organisations, which identify a project through an invitation to tender or similar sales channel, prepare a response and then, if successful, undertake the contracted work.

Note that a promoting organisation’s sublet ‘project’ may be a contracting organisation’s ‘customer project’. In both cases, the project has two distinct phases:

- The investigative stages, where the promoter determines how best to meet the objectives and the contractor determines the ‘bid design’, cost and price.

- The implementing stages, where the promoter and contractor undertake their planned work.

The distinction between promoting and contracting organisations is not always obvious, especially in the case where a contractor undertakes the operation of any outputs from the projects as part of an extended project life cycle. In more complex situations the distinctions should be clear within the contractual arrangements and formal authorities agreed between the parties.

Stages and gates

Stages

Stages are specific periods during which work on the project takes place. These are when information is collected and outputs created.

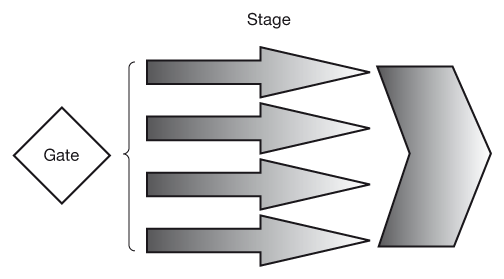

For each stage in the project, you should carry out the full range of work covering the entire scope of functional inputs required (Figure 3.3). These functions should not work on the project in isolation but in a continuous dialogue with each other, thus enabling the best overall solution to be developed. In this way your knowledge develops and increases on all fronts at a similar pace and solutions are designed, built and tested in an integrated way. No one area of work should advance ahead of the others. Your solution will not be what is merely optimal for one function alone but will be a pragmatic solution which is best for your organisation as a whole. This has the benefit of shortcutting the functional hierarchies, enabling the flat, lean structures we all seek to attain to work in practice as it forces people with different perspectives to work together, rather than apart. The business of the future, that is created and built using a cross-functional team, will find it much easier to run the all-encompassing cross-functional processes that business process re-engineers and the Theory of Constraints (see Chapter 21) tell us is the way forward. Further, you should limit the work undertaken in any stage to that which is needed at the next gate: there is little point in spending effort and money until you need to.

Figure 3.3 Address all aspects of the project in parallel

For each stage in the project, you should carry out the full range of work covering the entire scope of functional inputs required. In this way your knowledge develops and increases on all fronts at a similar pace and solutions are designed, built and tested in an integrated way.

RUNAWAY HORSES AND CATTLE DRIVES

A project is not a horse race, where the individual departments and functions are horses, each competing to see who can finish first. Projects are more like a cattle drive where all of the cattle must complete the run to market in tip top condition. Some cattle will be faster and stronger (better resourced), other cattle are yoked together (by process and functional hierarchy). As drivers, we must ensure that some cattle do not get too far ahead and that others do not lag behind. We must also ensure that they aren’t distracted by wolves (other projects) and scattered. But please don’t take the analogy too far and treat your people like cattle!

Figure 3.4 A typical stage

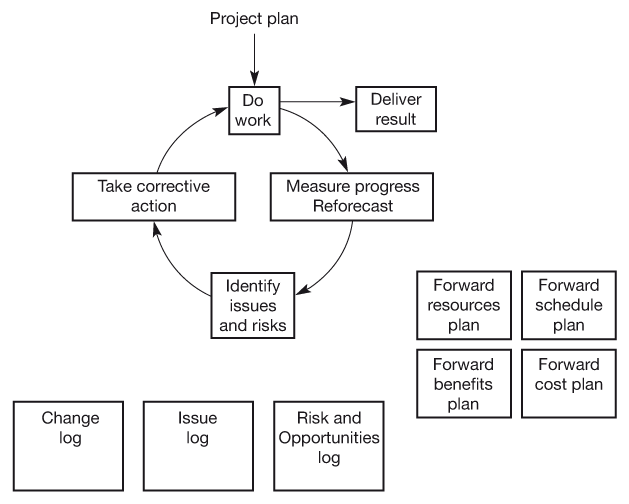

A stage may be represented by the project control cycle together with the key control tools you need to manage it (these are described in Part Four).

During each stage it is essential for the project manager to continuously forecast and reforecast the benefits, resources and costs needed to complete the project. He/she should always keep the relevant functions informed and check on behalf of the sponsor that the project still makes sound business sense. This is illustrated by the ‘project control cycle’ in Figure 3.4.

Before you start work on any stage, you should always know what you are going to do next in order to increase your confidence and decrease risks; you should have a project plan for at least the next stage in detail and for the full project in summary.

‘An unwatched pot boils immediately.’

H F ELLIS

Gates

Gates are the decision points which precede every stage. Unless specific criteria have been met, as evidenced by certain approved deliverables, the subsequent stage should not be started (see also p. 18). Gates serve as points to:

- check that the project is still required and the risks are acceptable;

- confirm its priority relative to other projects;

- agree the plans for the remainder of the project;

- make a go/no go decision regarding continuing the project.

You should not regard gates as ‘end of term exams’, but rather the culmination of a period of continual assessment with the gates acting as formal review points.

Gate criteria are often repeated in consecutive gates to ensure that the same strands of the project are followed through as the project progresses. You should expect a greater level of confidence in the responses to the criteria, the further into the project you move.

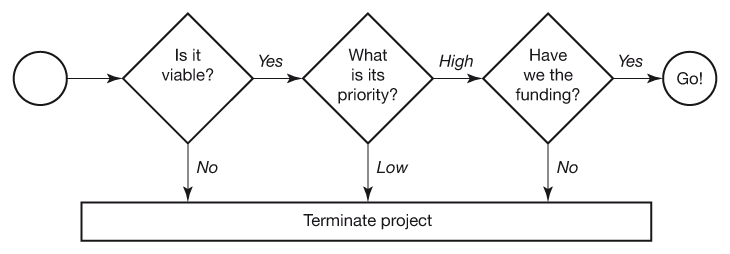

At each gate you will need to answer three distinct questions (Figure 3.5):

- Is there a real need for this project and, in its own right, is it viable?

- What is its priority relative to other projects?

- Do you have the funding to continue the project?

It is convenient to think in terms of these questions because, in many organisations, discrete people or groups are needed to address each of them.

Figure 3.5 The three decisions required at each gate

The first question concerns the viability of the project assuming no other constraints. Does it fit your strategy? Does it make business sense? Are the risks acceptable? You will see later on that this question is addressed by the ‘project sponsor’.

The second question (priority) concerns the project in its context. It may be a very worthy project but how does it measure against all the other projects you want to do or are currently doing? Are there more worthwhile projects to address? Is it just ‘one more risk too far,’ bearing in mind what you are already committed to? This question is dealt with in Part Three where I will propose a basic method of managing such decisions.

The third question involves funding. Traditionally, businesses have discrete and very formal rules concerning the allocation of funds and which are generally managed by a finance function. So, you might have a viable project, it may be the best of those proposed BUT have you the working capital to finance it? This question is also dealt with in Part Three. If your finance function is less dominant, the funding question(s) come before the question of priority.

Gates – an end or a beginning?

Gates have traditionally been defined as end-points to the preceding stage. The logic is that the work in the stage culminates in a review (viz. end of stage assessment) where a check is done to ensure everything is complete before starting the next stage.

However, due to time pressures, it is often necessary to start the next stage before everything in the previous stage has been fully finalised. For example, in the typical framework in Figure 3.6, we see that it is sound sense to undertake a trial operation of our new output before all the process, training and communication work is completed. What is essential is that we have sufficient work done to enable us to start the next stage with confidence. We are, therefore, left with the difficulty of having a traditional ‘rule’ that common sense encourages us to break.

The solution to this dilemma is to treat gates as entry points to the next stage. In this way you can start the next stage (provided relevant criteria and checks have been done) as soon as you are ready, regardless of whether or not the full work scope of the previous stage has been completed.

In this way, stages can overlap, reducing timescales, without increasing the risk associated with the project.

This approach also opens another powerful characteristic of the staged framework. Gates are compulsory, stages are not. In other words, provided you have done the work needed to pass into a stage, how you arrived there is immaterial. This allows you to follow the strict principles of the staged approach even if a stage is omitted. In Chapter 12, I will introduce the concept of ‘simple’ projects and show how this principle enables them to be accommodated.

The project framework

As we have learned, projects draw on many resources from a wide range of functions within an organisation. Ensuring these are focused on achieving specific, identified benefits for the organisation is your key management challenge. You can increase the likelihood of success for your projects, and hence of your business, by following a project framework which:

- is benefit driven;

- is user and customer focused;

- capitalises on the skills and resources in the organisation;

- builds ‘quality’ into the project deliverables;

- helps manage risk;

- allows many activities to proceed in parallel (hence greater velocity);

- is used by people across your whole organisation.

As we have already seen in Part One (p. 18), sound approaches to tackling projects achieve all these objectives by breaking each project into a series of generic stages and gates which form a framework within which every project in the organisation can be aligned.

This enables you to gain control of two key aspects of your business:

- You know that each project is being undertaken in a rational way with the correct level of checks and balances at key points in its life.

- You are able to view your entire portfolio of projects at a summary level and, by using the generic stage descriptions, know where each project is and the implication this has on risk and commitment.

The remainder of this part of the book concentrates on the ‘single’ project (point 1) and takes you step by step through a framework you can use on your projects. Part Three will describe the management of portfolios of projects (point 2).

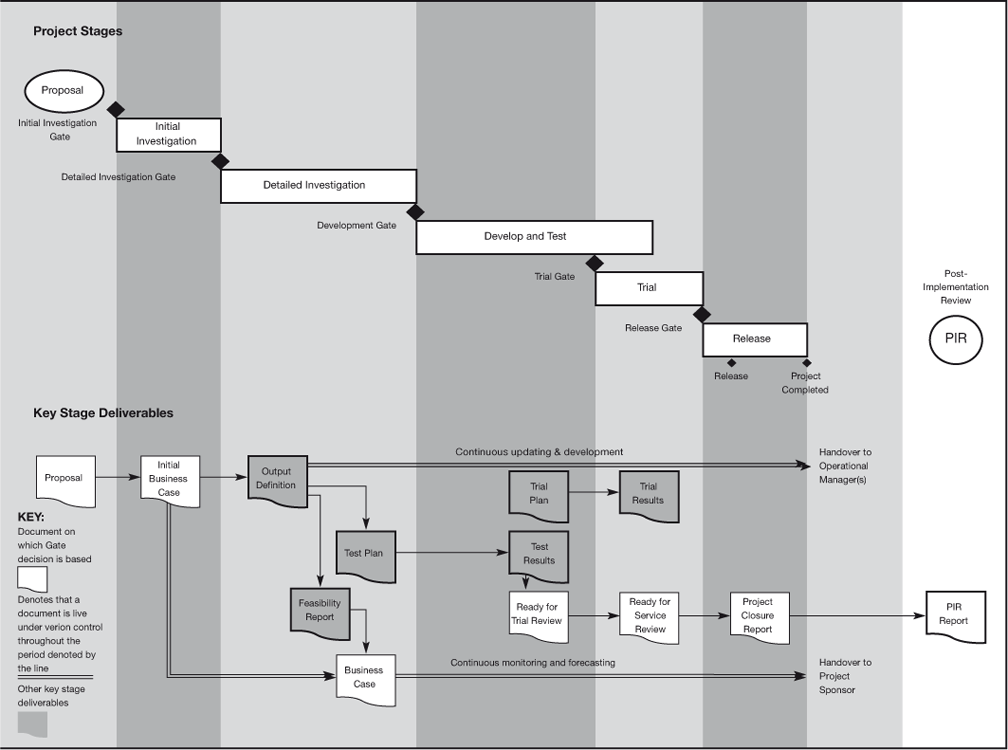

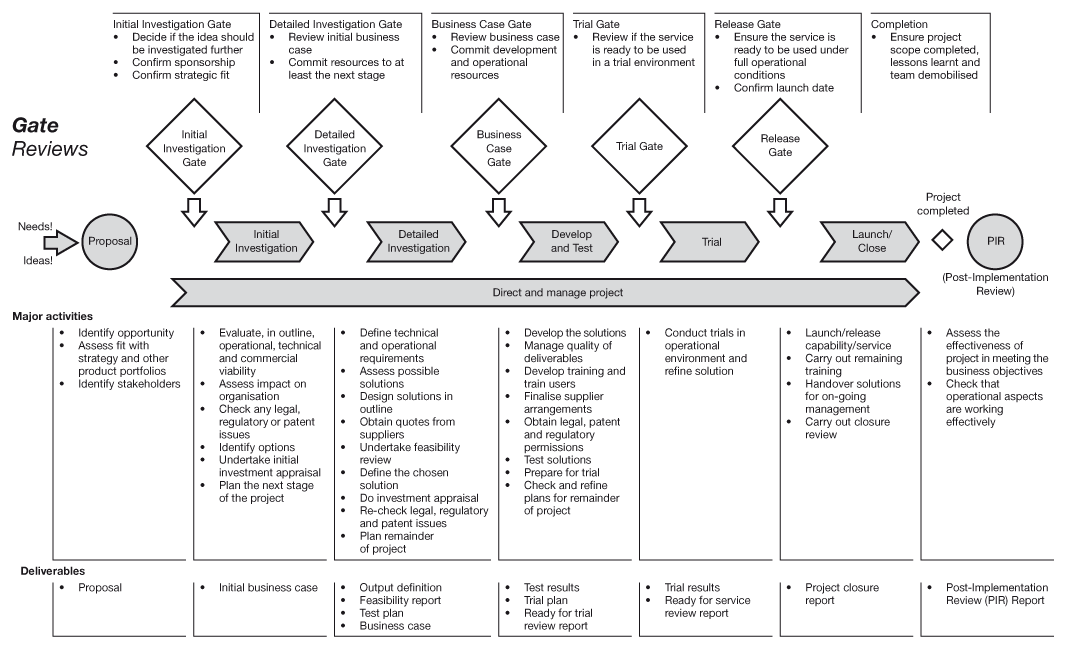

The project framework is shown in Figure 3.6 as a bar chart and in Figure 3.7 as a diagrammatic overview. The stages are, briefly, as follows:

Identify the need – Proposal: a need is first formally recognised by describing it (i.e. say why you want to initiate a project). If known, you should also describe what you believe the project will produce (i.e. its output) but don’t jump to conclusions too soon.

Have a quick look – Initial Investigation Stage: the first stage in the project – a quick study of the proposal, to outline the scope and make a rough assessment of the possible ways of meeting the need, benefits, resources and costs needed to complete it. At the end of this stage you should be sure of why you are doing it. You may also know what you are doing, although this may comprise a range of defined options. You will know how to go about at least the next stage, if not the full project.

Have a closer look – Detailed Investigation Stage: a feasibility study, definition and a full investment appraisal culminating in a decision to proceed with development work. At the end of this stage you will have high confidence in all aspects of the project and ‘What you wanted to do’ becomes ‘What you are going to do!’

Do it! – Develop and Test Stage: the actual development and implementation work.

Try it – Trial Stage: a trial of all aspects of the development in the users’ or customers’ operational and working environment. What has been created may work very well under ‘test conditions’, but does it work under normal operational conditions?

Use it – Release Stage: the last stage in the project, when you unleash your creation on the world. This is when products are launched, new computer systems used, new manufacturing plant goes into production, new organisation units start operating to the ‘new rules’, new processes are invoked, acquisitions sealed and disposals shed. The on-going operational aspects are embedded in the organisation and the project is formally recognised as complete.

About three to six months after completion, a check, known as a Post-Implementation Review, is done to see if the project is achieving its business objectives and its outputs are performing to the standards expected.

Figure 3.6 The project framework as a bar chart

The project framework is shown here in ‘bar chart format’ at the top, with the document deliverables for each stage shown below. These are described more fully in Chapters 5 to 11; see also the CD-ROM for more details on each document.

Figure 3.7 The project framework in diagrammatic form

The project framework is shown here in a format which clearly distinguishes between the gates and the stages. It also shows the activities and deliverables which relate to each stage.

PORTFOLIOS, PROGRAMMES, PHASES, STAGES and GATES

In this book I refer to STAGES and GATES as convenient descriptions for the periods when work is done and for the points in time when a check is made on the project prior to starting the next stage. Terminology often found in practice also includes:

For stage: Phase

For gate: Tollgate; Gateway; Quality Gate; Checkpoint; Assessment; Review

In this book, I reserve the use of the word ‘phase’ to describe a programme that is to be introduced or built with benefits designed to arrive in different time frames. For example, major roads projects are frequently introduced in phases so motorists can benefit from the first 20 miles built and do not have to wait for the full 80-mile stretch to be completed. Each phase is in fact a project in its own right and comprises a number of stages.

The word ‘programme’ is also problematic, much used and abused to the extent that it is often meaningless. For example I had a job title of ‘programme manager’, but I did not use it on my business cards as it did not tell anyone what I did; indeed it might even have misled them. Programmes are discussed more fully in Chapter 13 as a tightly aligned and tightly coupled set of projects. Note this does not conflict with the emerging view that programmes include the period of benefits realisation, as in the Project Workout, where all projects are business and benefit led.

The word ‘programme’ is frequently used to bundle any projects together for the convenience of reporting, planning, or other management purpose. In this book I refer to these as a ‘portfolio’. This is discussed further in Chapter 14 in relation to what I term ‘business programmes’. Just to keep you on your toes, ‘portfolio’ can also refer to bundles of programmes as well as projects.

In hierarchical terms the relationship is:

- the organisation’s portfolio(s) of programmes and projects;

- programme;

- project;

- stage.

The above terms can look confusing, mainly because there is no universal definition for them. Each organisation (or standards body) will choose its own definitions. The point therefore is for you, in your organisation, to choose what suits, visibly define the terms and use them consistently.

Some key questions

How many stages should I have?

Consider the types of project you undertake in your organisation. Do they fit the generic stages described earlier? Are there some modifications you would like to make? Some organisations have only four stages, others six or more. Generally, the fewer the better, but they must be meaningful to you and fit every project you are likely to do. My experience is that three is too few and five will fit most purposes, so if in doubt try five. Of the five stages used in this book, it is the Trial Stage which is often either left out (see ‘Is a trial really needed’ later in this chapter) or merged in with the Develop and Test Stage. I prefer to have the trial as a distinct stage to differentiate it from testing. Testing is very much an internal, ‘private’ activity. A trial on the other hand is ‘public’ involving real users and customers. You are therefore open to poor press comment and to hostile reactions from employees. By making the trial a distinct stage you force people to focus on whether they really are ready. There have been enough high profile cases of beta test failures of software and of premium automobiles receiving very poor press due to a poor state of market readiness to act as a warning to us all.

How do I decide what work is done in the investigative stages?

The investigative stages exist in order to reduce risk (see Figure 3.2). Therefore everything you do should have that aim. If any proposed activity does not reduce risk, you should consider postponing it to a later stage.

Avoiding looking foolish

A ‘wife’ is a ‘wife’ and a ‘husband’ is a ‘husband’. It would be ludicrous to call one a ‘husband-wife’ and the other a ‘wife-husband’! Similarly, a ‘stage’ is a ‘stage’ and a ‘gate’ is a ‘gate’; they are fundamentally different, so don’t make a fool of yourself and confuse others by using the nonsense term, ‘stage-gate’.

What should I call the stages and gates?

The stage and gate names I have chosen and used throughout this book have evolved over a number of years and are based on my experience of working in several organisations on different business projects. What you choose to call them is up to you but that decision is not trivial. Words are emotive and hence can be both very powerful movers for change or inhibitors of change. In all organisations there are words which:

- mean something particular to everyone;

- mean different things to different people.

You can build on the former by exploiting them in your project framework, provided the meaning is compatible with what you wish to achieve when using the words.

You should avoid the latter and choose different words, even making up new words if the dictionary cannot help you. For example, working in one company I found the word ‘concept’ problematic, despite its being very well defined and in the dictionary. ‘Concept’ to some people was a high level statement of an idea (the meaning I wanted to convey), but to others it meant a detailed assessment of what has been decided should be done (this was not what I wanted). Rather than try to re-educate people in their everyday language, I found a word (proposal) which had no strong linkages to current use of language. There were similar problems with the word ‘implement’: it has so many preconceived meanings that it is better not to use it at all! If you look at the list of possible names, you will notice that certain words appear in more than one place: this is a sure sign that they might be misunderstood.

The same issues apply to the naming of the gates. For these, however, it is better to name each one according to the stage it precedes. This emphasises the ‘gate as an entry point’ concept. An alternative approach is to name the gate after the document which is used as the control on the gate. You will see I have mixed these. Again this is your choice, but make the same terminology apply across the whole organisation.

I do, however, strongly suggest you do not refer to the stages and gates by a number or letter. It will cause difficulties later (including significant cost) if you need to revise your framework. You will not believe the number of times a ‘Gate 0’ or ‘Stage 0’ has had to be added to the front of a framework! Using proper names is simpler, more obvious and will not box you in for the future.

Where do people go wrong?

In designing their frameworks, I have found people make mistakes in two key areas, the front end and the back end.

All too often, I see frameworks with minimal start-up activity, immediately followed by the Develop and Test Stage. They have in effect gone from ‘idea’ to ‘do it’ in one small step. In all but the simplest projects such a leap is naive and may account for why so many projects are ill-defined and doomed to failure. By all means make it easy to start the project off (i.e. pass through the Intial Investigation Gate), but do ensure there is rigour in the actual investigations themselves. A project comprises both investigation and execution.

At the back end, people often confuse Project Closure with Post-Implementation Review. The former looks at project efficiency and delivery, whilst the latter looks at benefits realisation and operational effectiveness. These two views cannot be combined as the measurement points are entirely separated by time. Also note that ‘Proposal’ and ‘Post-Implementation Review’ are not stages of the project. They are activities which happen before and after the project, respectively; that is why they are shown as a circle and not an arrow in Figures 3.6 and 3.7.

Is a trial really needed?

‘I have already tested this rigorously. Surely I don’t really need to trial it all as well? Won’t this just delay the benefits?’

This is a very valid question. The answer, as always, is ‘yes and no’. Assume you have a choice of strategy from:

- product leadership;

- operational efficiency;

- customer intimacy.

- Under ‘product leadership’ you are developing and delivering innovative, new products and services; you must be sure they really work as intended. You are aiming to be first and best in your market.

- Under ‘operational efficiency’ you deliver what others deliver but more efficiently and at lower cost.

- Under ‘customer intimacy’ you provide an experience for your customers such that they want to do business with you.

Thus, if your strategy is to have any practical meaning you must be sure that anything you do does not compromise it. The choice of ‘to trial or not to trial’ comes down to risk. What is the likely impact on your business if this goes wrong? How confident are you that it won’t go wrong? With this in mind, you may choose to subject certain aspects to a trial more rigorously than others – balancing the speed to benefits realisation with the risks.

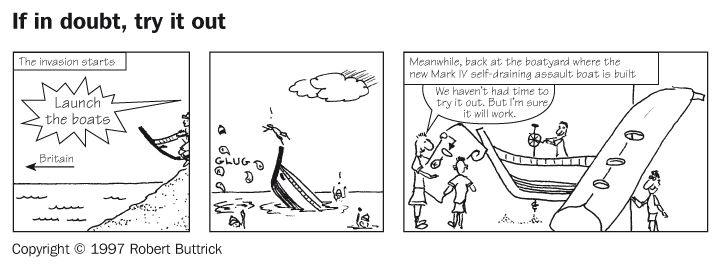

Always assume that you need a trial. Omit it only if you have proved to yourself and your stakeholders that it will not add any value to your project. Never skip the trial because you are in a hurry! If in doubt, try it out.

How can I apply the framework?

The staged approach is the framework for the management of any type of project, for any purpose. As such, it is flexible and provides project managers with the opportunity to tailor it to suit the requirements of their individual projects. This ensures an optimum path through the generic project framework rather than one which is tied by bureaucracy. Any such tailoring of the project must, however, be recorded as part of the project definition (see p. 298).

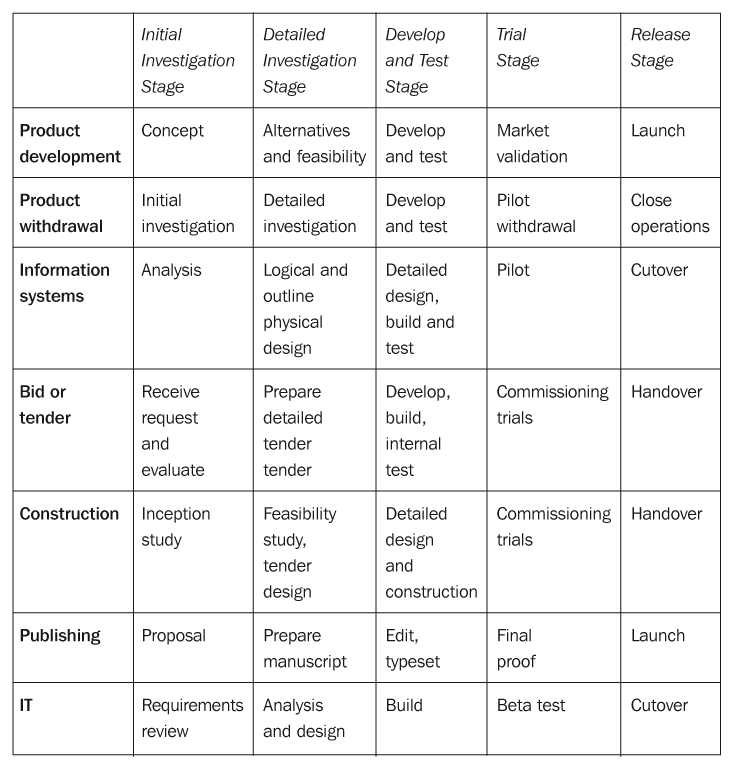

Particular types of project require their own methodologies and steps but, provided you know how they match the overall high level framework, they can be used with confidence and in an environment where the business also knows what is happening. A common project framework will ensure alignment between different parts of the organisation with clearer communication and understanding. The table opposite shows how a range of different projects can fit into the framework.

Chapters 5 to 11 of this book describe the key actions, deliverables and decisions for each stage and gate of the framework. Chapter 12 looks at how you can apply the framework to simple, complex, phased, rapid and other types of project.

3.1 TAILOR YOUR OWN FRAMEWORK

Consider the above list of different types of project. Do you recognise any from your own organisation? Can you add to the list? If so, reproduce Figure 3.7 with modified activities, deliverables and gate review criteria. You’ll find a blank template for this on the CD-ROM.

3.2 YOUR CURRENT BUSINESS PROJECTS

List the business projects you are undertaking at present in your organisation. Based on the simple descriptions just given, state which stage of the project life cycle each project is at. If you have completed Project Workout 3.1, use your own stage names; if not, use those in Figure 3.7.

Talking the stages

A product marketing manager is accosted in the corridor by an engineer:

Engineer: I just heard that you’ve got plans to muck about with my installation. You ignore me as usual. Why on earth wasn’t I told? It looks like a really big change!

Product Manager: But, Leigh, we only decided to start the initial investigation two days ago. I’ve told no one yet: the proposal goes out tomorrow.

Engineer: Sorry Bill. From what I heard, I assumed it was more advanced than that. I look forward to getting the proposal.

In this scenario, an interdepartmental conflict was diffused because, despite having totally different business backgrounds, they both understood the project framework for the organisation they worked in. If they had each talked in their own jargon (e.g. marketing concepts, pre-feasibility studies, inception reports) they would as likely as not have been none the wiser and continued their argument.