Managing What Might Go Wrong (Or Right): Risks and Opportunities

Considering possible risks and opportunities

Addressing risk at the start of the project

Addressing opportunities at the start of the project

Monitoring once the project is in progress

Tips on using the risk and opportunity log

More sophisticated risk evaluation techniques

Taking active steps to reduce the possible effects of risks is not indicative of pessimism, but is a positive indication of good project management.

‘It is certain because it is impossible.’

TERTULLIAN, c. AD 160–225

- Risk management starts when the project starts.

- Reduce the likelihood of threats materialising.

- Contingency plan in the event that threats do materialise.

- Focus on the ‘big ones’, but don’t lose sight of the others.

- Look for opportunities to increase benefits, but not at the cost of increasing risk.

- Plan for the most likely opportunities.

Considering possible risks and opportunities

Risk is any potential uncertainty, threat or occurrence which may prevent you from achieving your defined business objectives and benefits. It may affect timescale, cost, quality or benefits. All projects are exposed to risk in some form but the extent of this will vary considerably.

Opportunity is the possibility that your project may go better than you planned.

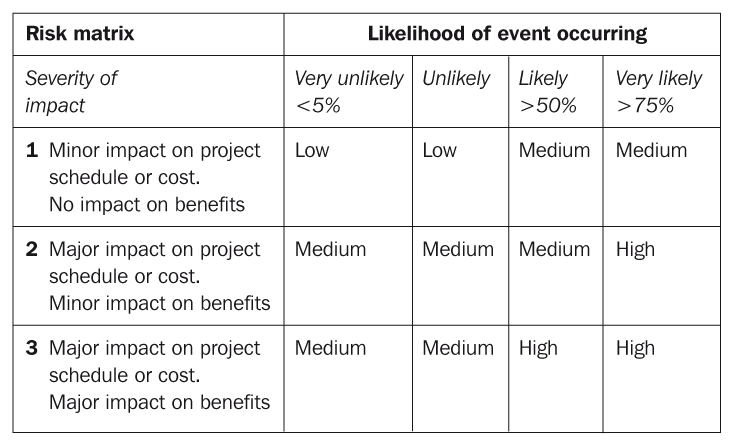

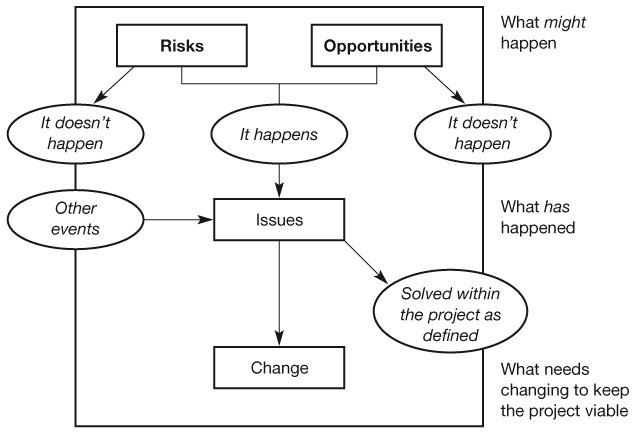

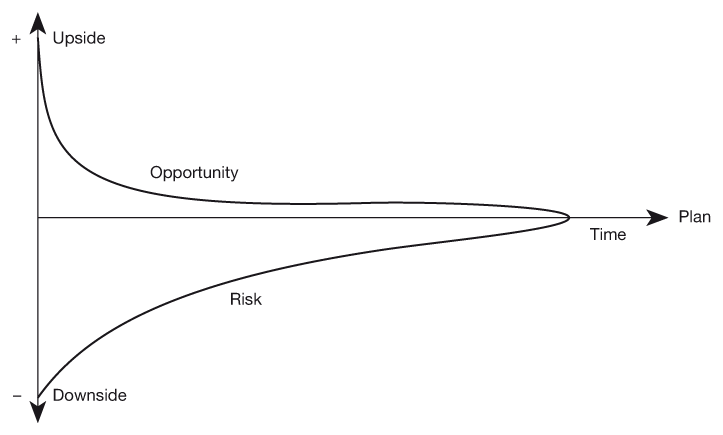

Figure 23.1 shows how risk and opportunity sit within the context of other project controls; a risk will become an issue if the event occurs. Issues can be resolved either within the scope of the project as currently defined or via a change to the project. An opportunity is similar to a risk but has a potentially beneficial impact rather than a negative impact. Like risk, an opportunity will become an issue if the event occurs. Figure 23.2 also shows that, once the project is well under way, the risk, or ‘down side’, is usually bigger than any ‘up side’ opportunities.

Figure 23.1 Risks, opportunities, issues and change

A risk or opportunity will become an issue if the event occurs. Issues can be resolved either within the scope of the project as currently defined or via a change to project.

Figure 23.2 Upside and downsides to a project

Once the project is well under way, the risk, or ‘downside’, is usually bigger than any upside opportunities. This is because people are usually optimistic.

The purpose of risk and opportunity management is to ensure that:

- risks and opportunities on projects are identified and evaluated in a consistent way;

- risks to the project’s success are recognised and addressed and significant opportunities are exploited without undue delay.

You cannot use risk management to eliminate risk altogether, but by careful planning you may be able to avoid it in some instances or minimise the disruption in others. But what if identified risks do not materialise? What if a new approach (opportunity!) comes about which will further your business objectives better than planned? You have two options:

- You can keep to the original plan, as something quite unexpected may still go wrong and eat into the time and money you’ve saved.

- You can build the new found opportunity into the project and ‘mine it’ for all it’s worth.

Traditionally, the former approach is the more prudent but that does not mean it makes the most business sense in all cases.

Addressing risk at the start of the project

You should address risk when the project is first being set up during the Initial Investigation Stage. Risk is an important section within the project definition; when a project sponsor approves a project he/she does so in full knowledge of the stated risks, accepting the consequences should things go wrong. It is important that the project sponsor accepts the risks as the person undertaking this role is the primary risk taker.

Often people are very good at identifying what might go wrong in terms of creating the deliverables, but less so at assessing what may go wrong in terms of benefits realisation. If your projects are truly business led, both are important. To ensure you do not forget this, think of your risks in terms of project risks and business risks. Project risks are those which impact delivery during the project, whereas business risks are those which will impact benefits realisation. Naturally a project risk, e.g. significant delay to the project, may also have an adverse effect on benefits. Don’t be too purist! The key is to recognise that there are some risks (often uncertainties), such as changes in exchange rate or competitor action, which are clearly not associated with project delivery, but with benefits (i.e. a business risk).

The steps are:

- Brainstorm all the risks that may jeopardise the success of the project. Remember to include those which are under the control of the project team (e.g. completeness of project scope, quality of technical solutions, competence of project team) as well as those which are largely outside the control of the team (e.g. legislative changes, competitor activity, economic climate). Use checklists to supplement the list after the brainstorm is complete.

- Review each risk in turn:

- assess the likelihood of the risk occurring;

- assess the severity of the impact on the project if it occurs.

- Use a risk matrix such as the one that follows to determine the ‘risk category’ (high, medium, low).

- For high risks, consider ways of preventing or avoiding the event, reducing the impact, or transferring the risk to someone else. Contingency planning is a last resort but, as the risk is high, consider making your ‘contingency plan’ the mainstream plan.

- For medium risks, take preventative, reduction or transfer measures. Failing that, prepare a contingency plan.

- For low risks, continue to monitor them as they may become more significant. Decide whether other action should be taken based on individual circumstances.

Taking active steps to reduce the possible effects of risks is not indicative of pessimism, but is a positive indication of good project management.

Many possible options exist for addressing risk, including:

Prevention – where countermeasures are put in place either to stop the threat or problem occurring or prevent its having any impact (avoidance).

Reduction – where the actions either reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring or limit the impact on the project to acceptable levels.

Transference – a specialist form of risk reduction where the impact of the risk is transferred to a third party such as a contractor or insurance organisation. Another form is where the risk is elevated to a higher level in the organisation, which effectively acts as an ‘insurer’ for a large number of projects. This approach is beneficial as it should lead to a reduction in the total amount of funds held in contingency.

Contingency – where actions are planned or organised which will come into force as and when the risk occurs.

Acceptance – where the organisation decides to go ahead and accept the possibility that the risk might occur and is willing to accept the consequences. (Not recommended, but all too often done!)

Consider also:

- bringing risky activities forward in the schedule to reduce the impact on the project outcome if they cause delays;

- modifying the project requirement to reduce aspects with inherently high risk, e.g. new, leading edge technologies;

- allowing appropriate time and cost contingencies;

- using prototypes and pilots to test the viability of new approaches.

Once past the Development Gate (see p. 66), a project should not usually contain any high risks. If it does, the project plan should be reconsidered to lower the overall risk by using an alternative approach or by introducing ways of reducing the likely impact.

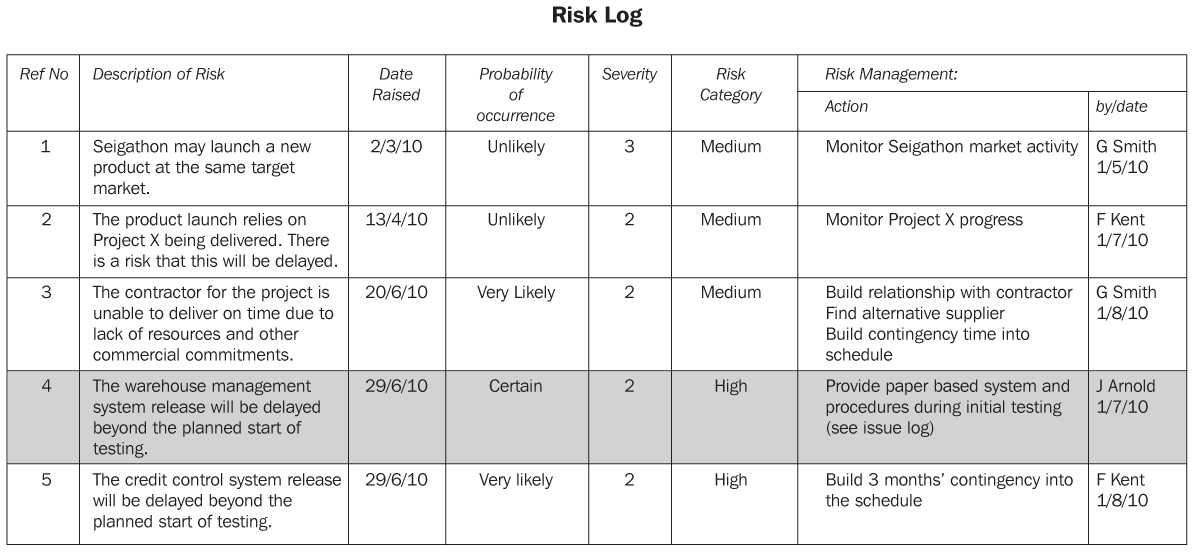

A convenient way of recording risk is in the form of a ‘log’ shown in Figure 23.3.

BEWARE THE DIFFICULTIES OF ‘RISK CONVERSATIONS’

To raise the subject of risk is not admitting failure. If the culture in your organisation is to see the discussion of risk as a failure, you must change it fast. Driving risk ‘underground’ is not the way to deal with it. If you are truly in control, there is every benefit in sharing risks and understanding the measures you can take to manage them. Research shows that addressing risk with your ‘eyes wide open’ is a significant factor in ensuring a successful project outcome.

Things still go wrong. Risk management is not infallible. Something may still happen which will destroy your project. For instance, irrational behaviour by individuals in your organisation, from competitors or from government cannot be predicted. Emotional actions and behaviours are often the most difficult to deal with.

Figure 23.3 A typical risk log

A risk log is used to record the risk, the date it was recognised, its category and risk management action (with accountability).

23.1 IDENTIFYING RISKS – 1

‘If a man begin with certainties, he shall end in doubt; but if he will be content to begin with doubts, he shall end in certainties.’

FRANCIS BACON, 1561–1626

This workout should be done with the project team.

- Use brainstorming or other creative methods to generate as many possible risks as you can. You should include anything that anyone wishes to raise. By involving the team you will start to develop an idea of where their concerns lie and what confidence they have in other team members or departments. In addition, group members will hear one another’s concerns and this also helps to form the team. Do not let anyone criticise or comment on any risk raised – just capture thoughts. Hint: look at any assumptions made and at any constraints (as listed in the project definition).

- Write each risk on a Post-It Note as it is called out; ask for clarification if the risk is not understood but otherwise do not allow comments.

- Put each Post-It Note on a board where everyone can see them. Carry on generating risks until the team have no more to offer.

- By inspection, cluster the risks into similar groups. This may be around technologies, people, legal, employee relations, funding, etc. Choose any clusters that ‘fit’ the situation.

- Rationalise the risks, combining some, clarifying or restating others; number each risk sequentially.

- Evaluate each risk using the matrix on p. 403 and plot all medium and high risks onto a flip chart.

- Take time for the team to review the output so far. Are there any themes noticeable in the risks or in the way they are clustered. Are there any particular aspects of the project which appear to be problematic?

- Begin with the high risks: start generating possible ways of dealing with them. Allow all options to be raised. Do not evaluate, just capture the possible risk management actions for later evaluation.

- Evaluate and agree which risk-management option should be followed and who is accountable for managing each particular risk.

Task – strive to eliminate any high risks.

- Avoid those risks you can, by using a different approach to the project for example.

- Build investigative work into your plan to drive out risks which result from having insufficient information.

- Capture your risks in a log (similar to Figure 23.3).

23.2 IDENTIFYING RISKS – 2

This workout should be done with the project team.

- Take the output from Project Workout 21.2 (the Post-It Notes network diagram) and display it on a wall.

- Start at the first Post-It Note and ask:

- What can go wrong with this?

- How likely is that to happen?

- What effect will that have on the timescale?

- Use the risk matrix to evaluate the risk category. Using a different coloured Post-It Note, mark up the risk and its category adjacent to the relevant part of the network.

- Repeat this until every Post-It Note in the network has been evaluated.

- Take time for the team to review the output so far. Are there any themes or noticeable streams of the project which appear to be problematic?

- Begin with the high risks: start generating possible ways of dealing with them. Allow all options to be raised. Do not evaluate, just capture the possible risk management actions for later evaluation.

- Evaluate and agree which risk-management options should be followed and who is accountable for managing each particular risk.

Task – strive to eliminate any high risks.

- Look for alternative way of approaching the work which avoids sequences of risks, creates contingency time, or brings risky elements forward.

- Replan the project around these risks putting your contingency (safety) where it counts.

- Capture your risks in a risk log (similar to Figure 23.3).

Addressing opportunities at the start of the project

You should address opportunities when the project is first being set up during the Initial Investigation Stage. Like ‘risk’, opportunities may influence your whole project strategy and plan. You should:

- Brainstorm all the opportunities that may potentially enhance the success of the project (some of these will be the converse of risks you have already identified).

- Review each opportunity in turn:

- assess the likelihood of each occurring;

- assess the impact on the project if it occurs.

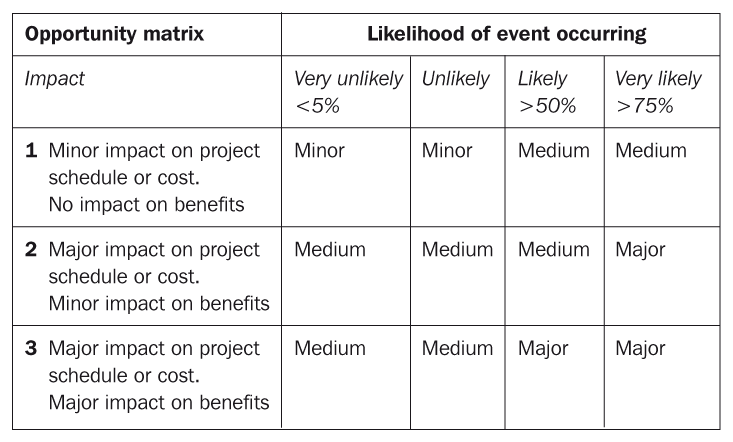

- Use an opportunity matrix, such as the one that follows, to determine the ‘opportunity category’ (major, medium, minor).

- For major opportunities, consider amending your baseline plan to build the opportunity in from the start.

- For medium opportunities, prepare an outline contingency plan you could use should it happen.

- For minor opportunities, take no immediate action; stay with your current plan.

There are many possible options for you to exploit, examples include:

- modifying the project timescale such that it is possible to bring the release date and hence benefits, forward should a risky aspect of the project proceed without undue problems;

- using time and money saved to incorporate outputs which originally had to be discarded (but make sure these really add benefit rather than are ‘nice to have’).

A convenient way of presenting opportunities is in the form of a ‘log’, similar to the risk log shown in Figure 23.3. This is very similar to the risk log and in practice you may choose to use the same log for both, marking them as a risk or opportunity, as appropriate.

23.3 OPPORTUNITY – 1

‘Probable impossibilities are to be preferred to improbable possibilities.’

ARISTOTLE, 384–322 BC

This workout should be done with the project team. Perhaps do this after the risk workout (Project Workout 23.1) to put a more positive light on the project.

Follow the instructions for Project Workout 23.1, but instead of concentrating on risks, look for opportunities.

Task – build all major opportunities into the base plan.

- Set yourself up to exploit opportunities by designing the project strategy and approach accordingly without compromising your risk-management strategy!

- Build into your plan investigative work to convert medium opportunities into major ones.

- Capture your opportunities in a log (similar to Figure 23.3).

23.4 OPPORTUNITY – 2

This workout should be done with the project team. Follow the instructions for Project Workout 23.2, but instead of concentrating on risks, look for opportunities.

Task – strive to exploit major opportunities.

- Look for alternative sequencing of the work which allows you exploit opportunities, should they arise, without compromising your risk-management strategy!

- Replan the project around these opportunities.

- Capture your opportunities in a log (similar to Figure 23.3).

An organisation had to upgrade some security features of its internal data network. This involved the upgrading of the software on two major associated computer systems as well as changes to a number of nodes within the network itself. Unfortunately, the upgrading of one computer system was seen as very risky due to its inherent instability and the number of other changes being made to it at the same time. The schedule showed a seven-month duration for the remainder of the project with the critical path passing through the problem software upgrade. No work on the network nodes could be started until this upgrade was done.

By following a sequence such as in Project Workouts 23.1 and 23.2 the project team identified that they could delink the network node work from the problematic software upgrade and allow it to proceed immediately (this involved a change to the upgrade specification in the second computer system). This simple change in the project approach resulted in the schedule plan of seven months having three months float in it; ample time to investigate and solve any problems on the computer system or to implement a manual alternative.

This exercise showed how team working produced a better result than any individual could – there was no one person who had the technical knowledge to devise the adopted solution. Further, the team formed a bond of understanding that stayed with them throughout the remainder of the project.

Monitoring once the project is in progress

Once the project has started, you should:

- Maintain a log of the risks and opportunities similar to the example given in Figure 23.3.

- Regularly monitor them with the team and reassess the likelihood of occurrence and seriousness of impact.

- Log, categorise and report new risks and opportunities together with the action being taken to deal with them.

- Report new, high risks in the regular project progress report (see Chapter 19) and highlight potential, significant opportunities.

During the course of a project, either of the following can happen:

- A risk or opportunity ‘event’ occurs – this should be noted in the ‘action’ column and a corresponding entry made on the issues log.

- A risk or opportunity event is passed, i.e. the project proceeds and the event does not occur. The category should be recorded as ‘none’.

In both cases, the log entry is ‘closed’ and the line in the log should be shaded to show that the event no longer requires management attention.

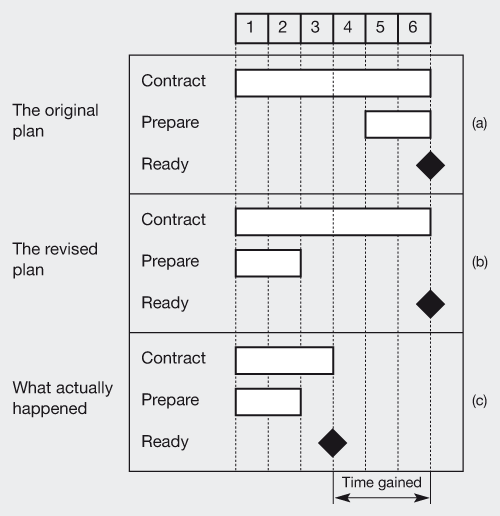

A major change project undertaken by an organisation relied on completing a contract with a third party for out-sourcing a part of their operations. The risk of being unable to sign a mutually beneficial contract was considered highly unlikely but it was considered that negotiations could be very long, at least four to six months.

The preparatory work for handover to the out-source organisation was expected to take two months and could take place in parallel with negotiations. Rather than delay starting this preparatory work, it was decided to proceed with it immediately so in the event of the contract being signed early the organisation would be in a position to bring forward the implementation date (Figure 23.4).

Figure 23.4 The effect of planning to create your own luck

In the original plan, (a), work would not start on preparation until the latest possible time in order to meet the required date. However, there was a possibility that the contract could be signed early and there was little risk of failing to sign. In plan (b) the preparatory work started as soon as possible. In fact, the situation that happened is represented by (c). The contract was signed early and the organisation was in a position to reap the rewards earlier.

Tips on using the risk and opportunity log

- Phrase each to fit the sentence ‘There is a risk (or opportunity) on this project that … caused by … resulting in …’

- Make sure your risks are truly ‘risks’ and not merely ‘worries’.

- Only have one risk or opportunity per ‘line’ – grouping can make managing them difficult.

- Do not add to existing entries, except to provide clarification.

- Cross-reference to the issues log when an event ‘happens’.

- Keep all risks and opportunities visible, even those which have been passed or have happened. This acts as a check in case others’ perception is different. Shading passed risks and opportunities makes it clear which are live and which are not.

RISK? OPPORTUNITIES? ISSUES? BUT WHAT DO I DO FIRST?

In managing a project you will always have to make choices about where to apply your time. Frequently there is not enough time or resources to manage every aspect of the project as fully or as rigorously as the ‘theory’ or the benefit of hindsight demands.

Having a framework within which you can deal with these aspects of project management helps ensure that they all have visibility and are not forgotten. When under time pressure you should concentrate on the ‘issues’ as they are now ‘facts on the ground’ and have to be dealt with. Delegate as many as you can, leaving the most critical for your own attention.

Next apply yourself to the risks. Your mission is to deliver the project according to the plan and keeping your eye on the future. Preempting future issues is part of that. Remember some risks are potentially more dangerous than issues. They are definitely more dangerous than opportunities.

Finally, look for the opportunities.

If, as part of the Initial and Detailed Investigation Stages, you have promoted a dialogue on risks and opportunities within your team (for example, by doing the workout exercises), the team itself will intuitively scan the environment for risks and opportunities on your behalf, thus sharing the workload. After all, what is a team for!

More sophisticated risk evaluation techniques

The basic approach to risk described so far in this chapter can be used by any person on any project. It requires no special tools, technical or statistical knowledge. In many cases it is the most powerful and effective approach, relying on the creativity and common sense of the team.

Nevertheless, there are occasions where other tools and techniques are very valuable for supplementing intuitive analyses.

Sensitivity and scenario analysis

So far we have looked at risk as a black and white occurrence. Either it happens or it doesn’t. In practice, however, there may be a range of outcomes, with impacts ranging from the disastrously negative to the unbelievably positive. You can identify such items easily; these are your assumptions. All assumptions are risks and should be treated as such. Examples are market rates, customer usage, plant efficiency, inflation, customer demand, cost forecasts and timing. For most projects, uncertainty will have a greater impact on the benefits than on project cost and schedule.

Sensitivity analysis is used to review the impact on the project of the possible range of values for each assumption made. In this way, you will be able to decide which assumptions are substantive to the case and need to be addressed further. The steps are:

- identify your assumptions;

- decide on a range of values for each assumption;

- rework your calculations (business model), using these values to see the effect on project viability on variations to that particular assumption;

- identify those assumptions which have most impact and log them as risks;

- decide on your response to these risks.

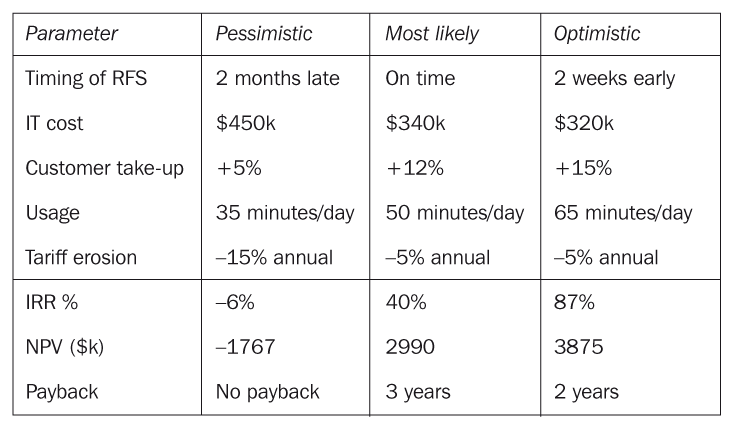

For example, in the following table, we see the project viability is more sensitive to percentage moves in tariff than costs.

Scenario analysis takes sensitivity analysis a step further by looking at alternative futures. A scenario comprises a set of compatible assumptions, chosen from the risk and sensitivity analysis, which describes the future. This often requires a model to be built so that the different assumptions can be used consistently, e.g. fewer customers may lead not only to less revenue, but also less cost of sales, while fixed costs may remain the same. Three scenarios should be investigated:

- optimistic;

- most likely;

- pessimistic.

Thus for a pessimistic scenario you may assume a late project completion date with a cost overrun with slower customer take-up and usage, with more severe downward price pressures than anticipated. This can be tabulated, for example:

As for sensitivity analysis, the aim is to provide decision makers with an objective view of what may be the consequences of continuing the project thus enabling them to balance the possible opportunities (up side) with the associated risks (down side).

Risk simulation

Risk simulation can be used to help analyse a project with respect to its most sensitive parameters and likely scenarios. It relies on the application of a range of durations, costs and benefits associated with a particular element in a project. This is input as:

- the lowest likely value;

- the most likely value;

- the highest probable value.

The simulation software will then analyse the network and calculate a range of likely costs and durations with a set of probabilities. The results are plotted on a chart such as that shown in Figure 23.5.

Figure 23.5 A typical output from a Monte Carlo analysis

The figure (created using Pertmaster Project Risk®) shows typical outputs you can expect from a Monte Carlo analysis. At the top is a histogram for costs, so you can place a percentage confidence measure on completing the project within a stated cost. The bottom screen is the same project, but shows the variation in schedule for a range of confidence percentages. In this example, we can be 85% confident the project will be completed by 21 October and for less than £9,200.

Software for critical chain scheduling (see p. 000) also includes risk and probability distributions to enable a rigorous plan to be built, tested and rolled out.

At the end of the 1990s a famous American hamburger restaurant chain decided to celebrate its birthday by providing cut-price offers on its leading product. The PR behind the event was superb. Not only did the advertising reach its target but also many news and magazine channels on radio and television as well as the press covered the forthcoming event. As it happened the consumer demand far outstripped supply to such an extent that many restaurants closed early and thousands of people had to be turned away. The event was dubbed by the press as ‘McBungle’. Was this a success? True, the advertising was effective, but what was the real cost to the organisation as its supply chain failed and its customers became angry? What of the financial cost in having to provide about four times as many cut-price meals as expected? What of the cost in lost revenue as the irate customers chose to use a competitor in future?

- How do you think the marketing executives viewed this campaign?

- How do you think the operations executives viewed the campaign?

- How did the hourly paid shop staff feel having worked harder and then had their day (and pay) cut short?

- What actions could have been taken to avoid the situation?

And remember, before you look at this with the benefit of hindsight, maybe they did do all the right things but Murphy’s Law proved too strong an adversary!