8

How to engage, evaluate and align employees

What you will learn in this chapter

- How to get employees more engaged (with your organisation)

- How to do a performance review that really means something

- How to align employees and figure out who does what

If you engage your employees, use performance reviews to help them develop their contributions and understand how these meet your overall objectives, and keep everyone clear about who does what in achieving these objectives, you will have achieved the management equivalent of walking on water. If this is you, read no further. For the rest of us, here are some ideas to help.

In my view, this is the single biggest management challenge we face. And many would suggest that we aren’t very good at it and are getting worse.1

Employee engagement

As with any buzzword, most of you will have heard of employee engagement. Many have a vague notion that it’s something to do with motivating and gaining employees’ commitment. Few actually practise it, and even fewer do it well. So what is it actually? The truth is there is no agreed definition, but employee engagement views the employer–employee relationship as one that is mutually beneficial for both parties. To quote one of the major reports on the topic:

A workplace approach designed to ensure that employees are committed to their organisation’s goals and values, motivated to contribute to organisational success, and are able at the same time to enhance their own sense of well-being.2

It sounds a bit soft and squidgy, but before you begin your eye-rolling, take a look at some of the evidence the same report presented:

- Performance A Gallup poll of 2006 found that the earnings per share (EPS) growth rate of organisations with high engagement scores was more than 2.5 times higher than those with below-average engagement scores.3

- Innovation CMI research from 2007 found that employee engagement had a significant association with innovation.4

- Absence Engaged employees take less sick leave, according to another Gallup poll.5

- Lower staff turnover According to the Corporate Leadership Council, engaged employees are 87 per cent less likely to leave the organisation than the disengaged.6

Arguably, engagement is even more important in recessionary times, when hiring freezes and cost-cutting make winning the hearts and minds of remaining employees even more vital. Without engagement, strategies cannot be well-executed, values are not brought to life and organisations can suffer from high turnover and inertia.

So how to go about engaging employees, and how is it measured? Here’s a simple seven-point checklist:

- Give staff clear information on the mission, strategy and purpose of the organisation.

- Help staff understand how their work objectives tie in with the organisation’s goals.

- Involve staff in decision-making (even if they don’t always get what they want).

- Enable people to have a certain amount of control and autonomy over their own work.

- Promote good relationships with managers, colleagues and a supportive working environment.

- Offer feedback on a regular basis constructively, including praise and support.

- Create opportunities for people to progress in their careers.

Other things, like open-plan offices, atriums or other places where employees can gather and communicate informally, and social intranets, can help boost engagement.

Typically, employee engagement is measured by staff questionnaires. Most involve selecting key questions from these questionnaires, using some sort of proprietary algorithm to create an engagement number, and then indexing this number compared with other organisations. If no one really understands the ingredients that make up the index, and nothing is ever done with it, it can become an end in itself rather than a useful means to an end.

Here is an example of the sorts of questions that comprise a typical engagement index:

- I am proud to say that I work for xxx.

- I would recommend xxx as an employer.

- I am willing to go the extra mile for xxx.

- I intend to be working for xxx in 12 months’ time.

- Overall I am satisfied working for xxx.

Measuring the index is one thing, doing something about it is far more important. One of the pitfalls of taking the questionnaire too seriously is that you pay more attention to getting a high score on the ‘right’ questions than creating actual engagement. I recall one organisation where the rumours were that every year the survey came round this particular manager locked his employees in a room and said their bonuses would be dependent upon their scores – something they then repeated with their employees. Little wonder the scores were top-notch. But were they real? At the other end of the spectrum, I have seen employees become very disenfranchised with such surveys because year after year they are done, often with mediocre results, and yet nothing ever happens to address the results. I have also seen organisations where the results are ‘edited’ before being presented to the Board.

None of those behaviours is going to improve engagement. So if you do surveys, take them seriously, share the results openly, and take action to improve the results, preferably by involving those who provided the feedback and committing to measure improvements. Finally, remember that it’s better to have a clear idea of what to do better, and that many things that will influence your scores, not least culture. Different cultures score differently when it comes to things like enthusiasm, pride and personal identification with goals.

exercise

Do you measure engagement in your organisation? If so, how? If not, why not? How do you benchmark your results? Why do you think that is, and what’s needed to improve? Dig out the last three years of surveys. Has anything moved? If not, why not?

Performance reviews that improve performance

Performance reviews are something that every organisation does, but astoundingly few, in my experience, do well. Indeed, maybe this is one area where technology has let us all down. There is little more disheartening than receiving loads of automated email messages that your annual performance reviews are now overdue. You then log in to a clunky system that administers the review, and makes it hard to see the data, crashes frequently, and makes reviewing people a terrible ‘tick-box’ chore. Little wonder they are frequently the subject of lots of headlines such as these, from the Management Innovation Exchange (http://www.mixprize.org/tags/performance):

“When Best Practices Aren’t Good Enough – Putting the Performance Review on Review”

“Blowing Up Performance Management 1.0 from the Inside: How One Manager Transformed His Company’s Approach to the Dreaded Performance Review”

Annual performance reviews are done in most places. However, the best way of managing performance is on an ongoing basis, every time you have a meeting with your employees. Immediate, consistent, specific and positive feedback is likely to be much more effective than a one-off review. Nonetheless, formal systems are required in most organisations so here’s how to get the best out of them.

Personally I think old-fashioned written reviews are much better than the online formats. The best performance reviews ask about your contribution to business objectives, to organisational objectives, your ability to interact effectively with others and develop people, your strengths, your development areas, and finish off with a personal development plan. There will usually be a five-point rating scale, with 1 being outstanding and 5 being unacceptable. Other features may be integrity, customer focus, values, exemplifying leadership, setting priorities, ability to collaborate, and so on. The review should also include a section for career goals and aspirations.

Ten steps to better performance reviews

You will have a more effective performance review if you follow these guidelines:

- Make sure you ask your direct reports to do their own. This ensures that they are thinking about their own contributions.

- Ask that everyone obtains 360 degree feedback – i.e. feedback not only from you, their boss, but also from people they manage and peers, which can be people they work closely with in other departments.

- Use the ‘Start–Stop–Continue’ framework – it is simple and effective: What should x continue doing to be more effective? Start doing? Stop doing?

- Schedule a face-to-face meeting to review what has been written. Start by listening to the employee’s own evaluation. What went well? What are they proud of? What went less well? Most people will be honest when they speak, even if they have over- or underrated themselves on the form. Then discuss.

- Emphasise the positive things, and discuss what they did to achieve these results. Encourage them to apply those behaviours to other areas. Make sure you end on a positive note.

- Be honest. The most common mistake is to overrate people! Someone who has missed every objective is rated as excellent, then, when it comes time to performance manage the person, they take action because they can cite a slew of glowing performance reviews.

- Use specific examples, not sweeping statements such as ‘you are too emotional’. Discuss how the person might have handled a situation differently. Equally, be specific with positive examples: ‘Your presentation to that client really captured their needs and how we could help. I’m sure it was a major factor in our win.’

- Draw up an action plan to improve the given areas. Make sure you try to draw on the employee’s strengths. For example, if someone is a great networker, but has difficulty sticking to priorities, encourage them to check with their colleagues and with you as to whether they are on track.

- Make sure you contribute to the action plan. What behaviour will they do differently? How will you help them? Draw up a plan to encourage both of you to help each other. Make sure your action plan addresses both performance and career goals.

- Feedback on progress frequently; weekly is not too often.

exercise

Plan to review your team’s performance weekly using the above approach for the next eight weeks. After two months, review the approach with each individual. Are you gaining better performance as a result?

Ideally, performance will affect both pay and promotion opportunities. However, there are some pitfalls. Many organisations used to have forced rankings, such as a certain number of employees in the top 10 per cent and firing those in the bottom 10 per cent. These have moved out of fashion, as it was found that over time the bottom 10 per cent became a political tool used to isolate people for personal rather than performance reasons. However, some sort of calibration on rankings is really important. Otherwise, you will find some departments where everyone is rated outstanding and others where everyone is rated average. If your pay is linked to performance, as it often is, this can be very discouraging.

Most organisations that manage talent well always distinguish between performance and potential. Someone may be a great performer, but be at the top of their level. Others will have loads of potential, but may be too inexperienced to be performing at a high level; so sending them a message that they are great is confusing, and will not help them realise their potential.

All performance reviews should indicate when the individual might be ready for promotion. To avoid creating undue expectations, the section on potential and promotion might be kept confidential.

Although everyone requires some degree of acknowledgement for a job well done, people are motivated by different ‘awards’: for example a bonus, instant thank-you, certificates or public announcements. Award ceremonies are often a good thing and many companies do these very well. It is especially effective if the employees do the nominating and the leaders judge the awards. They have the added advantage of forming ‘case-studies’ of success.

Beyond that, make sure you have the ability to recognise people on the job for the little things they do well. This can be by thanking them or with small rewards. In the end, nothing substitutes for a genuine and specific thank-you from managers and, when appropriate, from their managers.

Decision-making clarity

Life used to be simple. You worked for one person, and he or she sat in the office above you. If you were the boss, you had full responsibility for your site or business unit, department or country. Now, organisations are much more complicated, with multiple business units, countries, divisions, customer groups and functions. Departments and responsibilities are often shared by several stakeholders. This can result in lack of clarity over who does what, and who makes decision. Such ambiguity often results in conflict, inertia and poor performance. In my executive career, the ‘who decides what’ question has often been the major reason behind executive squabbles, power plays and intrigues. Dealing with decision rights is essential. Ultimately, this requires great leadership, because it’s about creating a culture where everyone feels that they want to move ahead, on the basis of common objectives and personal accountability rather than maximising their own power base. Poor leaders will ignore these conflicts and let them fester, maintaining that ‘big boys and girls’ will solve everything themselves. They won’t, and the organisation’s culture and performance will suffer.

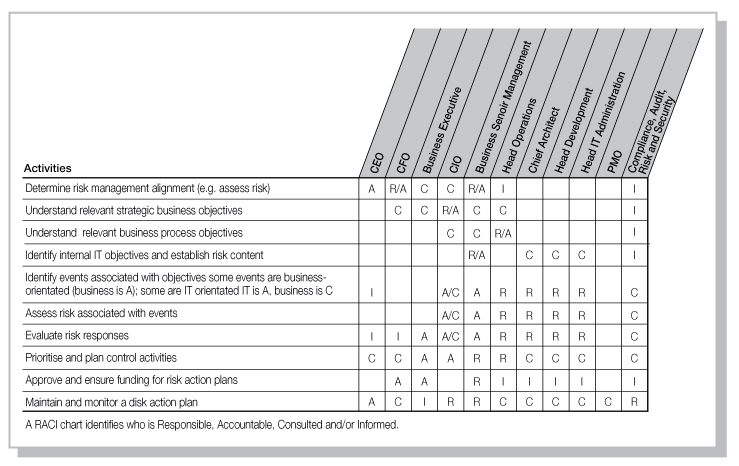

Tools can help, however. A useful one is the RACI model (see below). It is no substitute for a great culture – I once spent a weekend with colleagues trying to sort out a RACI, but no one wanted to collaborate, so it was a waste of time. So don’t use this tool until you are all ready to work together. And make sure the boss is there to take the call in the cases where people cannot agree.

The RACI tool

- Responsible This is the class of people who are ultimately responsible for getting the work done. This may refer to the individual workers who perform the given task or it could refer to the system if the task is automated.

- Accountable This is the class of people who are accountable to oversee that the work gets done. This usually means the immediate manager overseeing the work.

- Consulted These may be subject matter experts who need to be consulted when necessary, for example when an unanticipated scenario arises. These are the people who will recommend deviations from the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP).

- Informed This is the class of people who have some interest in the performance of a given task. This may be a manager trying to control the execution of the task at hand. Also this could be an input signal to the other process.

Basically, with the RACI tool, you map the people or functions that decide down one side and the activities or processes that need doing and deciding down the other. The output is shown in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1 The RACI matrix

Source: COBIT © 2007, IT Governance Institute. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Rules for using the RACI matrix

- Only one Responsible and Accountable Person Only one person should be assigned the R/A roles. Having more than one person responsible for the same task increases ambiguity and the chances of the work not being performed, and of duplication. Having more than one accountable person again leads to the same problem. However, having only one person accountable also leads to a problem. If the assigned person is incompetent the whole process fails. For this reason there is often a hierarchy of accountable people.

- Responsible-Accountable is mandatory The consult or inform roles are not mandatory for every activity. It is possible that some activities may not require them at all. But the Responsible-Accountable roles must be assigned.

- Communication with the consultant There must be a two-way channel of communication with the consultant. The important aspect is that the communication be two-way.

- Inform the required stakeholders This is a one-way channel of communication.

exercise

When your next big growth initiative or other project comes along, use the RACI model to plot out just exactly who is responsible for what before you begin. Then revisit every two months. Is the group sticking with the initially agreed responsibilities or are they shifting? Discuss as a team, including any adjustments to behaviours or realignments in RACI that need to be done.

The matrix doesn’t have to be your enemy

12 September 2012 Forbes.com

By Paul Rogers and Jenny Davis-Peccoud

It’s a world of multiple bosses, endless relationships, and – as this example shows – murky accountabilities. It’s also a world of frustrated managers and employees, people who feel that they can’t take effective action or deal with a customer without running into a series of organisational obstacles.

Some form of matrix – or organisational structure – is essential for running any large company. As companies grow, they become increasingly complex, especially in today’s world. When executives talk about crossing organisational boundaries, they usually mean not one or two boundaries but five or six, such as function, geographical region, process, product and customer.

To make this multifaceted system work . . . a company needs to focus on its decision-making processes, not its organisational chart.

Here are just a few of the steps your company can take to do that:

- Follow the money. High-performing companies know how each side of the business creates value and which decisions are key to unlocking that value. That helps them locate critical decisions at the appropriate points in the organisation.

- Align people around key priorities and principles. Most successful companies operate according to a set of core principles and priorities that supersede any matrix. These principles create a context enabling people anywhere in the organisation to make appropriate trade-offs.

- Assign clear decision roles. People can have more than one boss, but decisions can’t. The most common problem we find in matrix organisations is confusion over who should play which role in key decisions.

- Help leaders set the right tone. If leaders don’t make good decisions quickly, others are likely to dither. If leaders don’t collaborate across boundaries, others won’t either.

- Foster a performance culture. This is the holy grail of decision effectiveness: an environment in which people naturally take responsibility for cross-boundary cooperation. It’s critical for a smoothly functioning matrix as well.

Top tips, pitfalls and takeaways

Top tips

- Always have clarity over who makes the decisions.

- When managing someone, give constant and honest feedback on their performance; don’t just save it up for the formal review.

- The RACI tool for defining accountability has stood the test of time. It refers to being: Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Informed.

Top pitfalls

- Proceeding with a tool for accountability when the culture is weak and people don’t trust each other.

- Setting up employee questionnaires, but not acting on the findings.

Top takeaways

- Employee engagement is not a fuzzy thing: it can make a huge contribution to financial returns and better risk management.

- Face-to-face reviews, with regular follow-ups, can be far more effective than online once-a-year box-ticking versions.

1 Conference Board CEO Challenge Report, 7 June 2013.

2 Macleod Report, p. 9.

3 ‘Engagement predicts earnings per share’, Gallup Organisation, 2006.

4 Kumar, V. and Wilton, P., ‘Briefing note for the Macleod Review’, Chartered Management Institute, 2008.

5 Gallup, 2003, cited in Employee Engagement: How to Build a High Performance Workforce, Melcrum Research Report Executive Summary, Melcrum Publishing, 2005.

6 Corporate Leadership Council, Corporate Executive Board, ‘Driving performance and retention through employee engagement: a quantitative analysis of effective engagement strategies’, 2004.