1

What kind of manager are you?

What you will learn in this chapter

- What kind of personality and management style you have and why it matters

- Understanding and using your strengths to have a positive impact on others

- How to develop an ethical framework for taking management decisions

- How to handle stress and maintain a work–life balance

Who are you?

The answer to the question, ‘What kind of manager are you?’ begins with who you are as a person. Yet one of the most difficult tasks for a manager is developing self-awareness. That is why so much of modern management development focuses on psychological profiling to help managers better understand themselves.

The most widely used of these personality assessments is called Myers Briggs.1 Indeed, every organisation I have worked for has used this tool as part of its management development programme. It has been taken by over 50 million people and used by over 10,000 companies, 2,500 universities and 200 government agencies in the US alone.2 Originally developed to help women enter the workforce during World War II, it is based on the theories of Carl Jung and has sixteen distinct personality types.3 Which one you are is defined by four different areas:

- To recharge, do you spend time with people (Extrovert) or your thoughts (Introvert)?

- Do you perceive information more through your senses – tangible things you see and touch such as data and details – in the present (Sensing), or more through your gut-feeling, hunches and concepts with a view towards the future (Intuitive)?

- Do you make decisions primarily based on analysing situations (Thinking) or more on how your emotions are responding (Feeling)?

- Do you prefer to have a plan and act? (Judging) or stay open and adapt (Perceiving)?

The resulting four-letter combination defines your personality: for example, I am an ENTP (where N stands for intuitive).

Whether you use this or another personality assessment, understanding more the kind of person you are is a vital element to becoming a better manager.

The concept of being you at work is a powerful one. Suppose that you are a natural right-hander but you are forced to write with your left hand. You would find that awkward. Now imagine that you had to produce a book for work, and so had to write with your ‘wrong’ hand, day in day out, for hours at a time. The same is true for management. If we cannot be ourselves, and have to subvert or redirect who we really are, we quickly become more stressed and less effective. That is because too much of our energy is invested in suppressing who we naturally are and pretending to act in a way that we would not normally do.

Now imagine the opposite: you are totally in synch with yourself, doing what comes naturally, able to focus completely on the people and tasks around you without being self-conscious, achieving a great deal in what seems like very little time. That is called Flow. It leads to greater happiness and fulfilment, as well as increased productivity. Be yourself at work and ‘go with the Flow’.4

Management styles

As a manager, one of your key responsibilities will be to ensure your department, team or area of the business delivers its objectives. The way in which you deal with people will have a big impact on how successful you are as a manager. Therefore, becoming aware of your management style and its impact on others is really important.

There are many theories of management style. For me, the best of these deploy the simple idea of people and tasks. If you are focused on both the people and the task, you are going to get the best results. If you are focused on neither, you are going to get no results. If you are only focused on the task, you may get things done but risk harming relationships. If you are only focused on the people, they may like you but you probably won’t get much done.

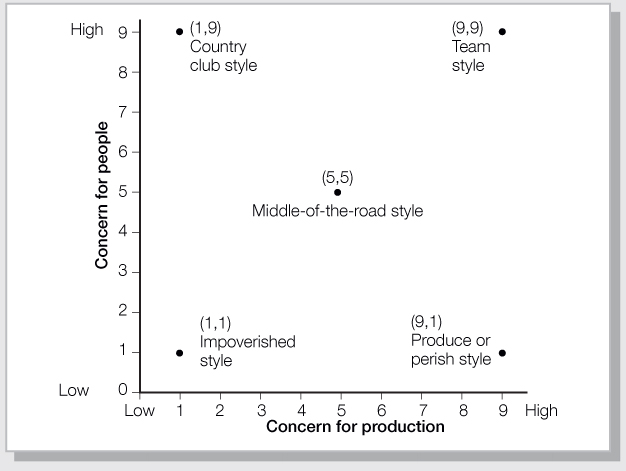

One summary of this is called the Management Grid, developed in the 1950s and 1960s by Robert Blake and Jane Moulton. It describes different management styles as follows:5

- Impoverished management Little concern for either the task or the people. This style involves little more than going through the motions, doing only enough to get by. These are called the ‘slackers’ or those who are ‘disengaged’.

- Authority-obedience High levels of concern for task and low for people. This represents a controlling style, close to the traditional ‘command and control’ approach, but runs the risk of damaging human relationships. If you are a nice guy, then this style can also be benevolent, autocratic or paternalistic.

- Country club leadership High levels of concern for people and low for task. This is seen as accommodating – it may create a warm and friendly working environment but at the cost of getting the job done efficiently. This is the guy or gal who takes all his or her reports out for endless team lunches, team-building days and drinks, but doesn’t really manage their output.

- Team management High levels of concern for both task and people. This is seen as the most effective style with the potential for high achievement. Of course, you also need to manage various individuals, as well as teams.

- Middle of the road management Moderate level of concern for task and people. This achieves a balance between task and performance but is likely to perpetuate the status quo rather than achieve notable success. It can also be quite bureaucratic and resistant to change.

I have seen all of these styles at work over the years. Do you recognise yourself and your colleagues?

exercise

Plot yourself on the graph in Figure 1.1. Then ask one peer, one direct report and your boss to do the same. Do the descriptions of your style match up? What are the key differences? Ask for specific examples and feedback to explain them.

Figure 1.1 The styles of management grid

Situational leadership

How you manage also depends on the situation, and you need to flex your style accordingly. Doing so is called situational leadership. If you are in a crisis, you may need to be more directive – you don’t want to ask people which fire exit they prefer or hold a vote on who should leave the burning building first. The style you apply can change over time, and, indeed, managers should change their style over time to reflect the shifting capabilities of their people and the organisation. The skill levels of people also matter, as does their motivation. If you are overseeing lots of unengaged, low-skilled people, then you will need to behave differently than if you are in charge of highly motivated and qualified people who have been working together a long time. Our One Minute Manager guru, Ken Blanchard, also thinks that how you manage others depends on who you are leading and their skill level and commitment, as he explains below:6

- A telling/directing style when they are both unwilling and unable.

- A selling/coaching style when there is some competence but a lack of commitment.

- A participating/supporting style where they are competent but unwilling or insecure.

- A delegating style where competence and commitment are both high.

Which style is most effective? The answer is it depends on both the situation and the context, but, generally speaking, high concern for both people and task will get the best results. This is a shift away from the ‘command and control’ or paternalistic styles that were very prevalent earlier. Sadly, however, the most common styles in the UK and US are still autocratic-bureaucratic. And we wonder why the economy isn’t growing.7 We will explore how to develop each of these styles more fully in Chapters 7 and 8.

Leading from strengths

We all have innate strengths, so one would think that we would rely very heavily on these in our role as managers. And yet we don’t. According to a Google lecture by Carolyn Foster, when Gallup, the famous opinion poll organisation, asked 1.7 million people all over the world whether they could use the things they were best at in their workplace every day, only 20 per cent said yes.8 When we do performance reviews, far too many of us focus on areas where we need to improve, and spend too much time trying to ‘fix’ weaknesses rather than grow strengths. We should focus on using the things we are good at, more effectively. We can use our strengths to mitigate our weaknesses.

Think about your talents – things that come naturally to you. Think, too, about talents that you do not use much but would like to develop. There’s a useful survey at http://www.viame.org/survey/Account/Register ‘Values In Action’, created by Dr Seligman.9 Any strength, however, taken to the extreme, becomes a weakness. For example, if your natural strength is to be able to seek harmony, this can lead you to shy away from taking difficult decisions. Try to use offsetting characteristics to keep your strengths from becoming too much of a good thing, and ask people for feedback to help you. It also helps to have diversity of strengths in teams as discussed in Chapter 9.

In addition to strengths that are uniquely yours, there are some ‘freebies’ – strengths we can all access if we choose, and which increase our levels of satisfaction in working and personal lives.10 These are:

- Zest This is about unbridled enthusiasm and vitality, fuelled by the ability to make a difference in our world.

- Curiosity Our intrinsic interest in our internal and external environments.

- Optimism Thinking that troubles are transient, limited and controllable.

- Gratitude Go thank someone. Write down three things to be grateful for twice a week – apparently this is the most effective discipline of all.

- Giving and receiving appreciation Remember, the absence of recognition is why people leave jobs. So this is vitally important.

Once you start to know your strengths, don’t try to do everything at once. Take it a step at a time. Otherwise you’ll be overwhelmed, as will those around you, and you may end up being less effective.

Be aware of impact

How you behave will have a great impact, and it is the simple things that matter. Saying ‘good morning’ and ‘thank you’ – sincerely – is crucial to getting people behind you. I learned this lesson early in my career as a brand manager. I was overseeing a major launch, and after two years we were ready. The $200 million factory had been built; over 50 million samples were ready to go, and the competitors were at our door with their versions of the product. It was tense and the stakes were high. I had become obsessed with getting this task executed perfectly. I had three young brand assistants working for me – all very different people. One day, they all came knocking at my door.

‘We need to speak to you’, they said, coming into my office and shutting the door behind them. ‘You never say “Hi” to us, or address us as people. Each day, you just storm into the office, head down, straight into your own office, and shut the door. It’s terrible. You make us feel like you don’t care. Like you don’t value us.’

That was a wake-up call. I changed my behaviour after that, and we went on to build a really strong team, and together launched one of Procter & Gamble’s most successful regional brands ever.

In today’s digital world, the human touch is arguably even more important. Recently I led a session at a company where the employees were not feeling engaged because the managers did not make them feel valued. At a workshop asking which behaviours could improve, the common element across all the groups was recognition – often in the form of simple everyday actions.

The importance of ethics and values

In 2013, we are still feeling the effects of a global financial crisis and a recession predicted to last another several years. What is its root cause? Bankers, insurers and government regulators all behaving badly, according to many people. Why and how did this happen? What can we do differently as managers to make sure we don’t slip into selfish, harmful ways? The answer is to develop a moral compass – and that means to develop ethics and values, and ensure we take them with us to work.

Ethics and values are about doing what’s right and having some form of principles alongside just profits or progress. But which principles are right and how should we decide? One approach to this very timely subject uses the concepts of ‘Ethicability and Moral DNA’. In his book, Ethicability, Roger Steare talks about three different forms of ethics: the Ethic of Obedience, the Ethic of Reason and the Ethic of Care.11

The Ethic of Obedience is about obeying rules of law or codes of conduct; the Ethic of Reason is about analysing what is wise and exercising self-discipline; and the Ethic of Care is about what is helping humanity, respecting human dignity and showing empathy for others. All of these ethical dimensions have been recognised by philosophers since Aristotle and Confucius, although what is new is what Steare does with them. He started testing people along all three dimensions, using an online tool he calls Moral DNA. Based on the results of over 50,000 people from all over the world, he makes some pretty interesting observations:

- We are different people at home than at work. At work we have more obedience, more reason and less care than at home.

- Women generally have higher levels of all three ethical dimensions than men; this is especially true of the ethic of care.

- As we get older, our ethic of care stays more or less constant, whilst our ethic of obedience declines and our ethic of reason increases.

Given that most of the bankers and executives involved in the financial crises were older males, it seems that it was very easy for them to be more selfish, less caring and to write their own rules. The UK Labour politician Harriet Harman MP famously said, ‘Financial crises might have been avoided if we’d have had Lehman Sisters.’

So how should we ensure we bring ethical decision-making back into our workplace?

Steare offers up something he calls the RIGHT12 acronym. It means we ask ourselves the following:

- What are the Rules?

- Are we acting with Integrity?

- Who is this Good for?

- Who could we Harm?

- What’s the Truth?

Steare’s work also suggests that if we behaved more authentically, more in tune with our ‘at rest’ selves with regards to ethics, we would make better, more ethical decisions. Companies sometimes try to bridge the gap between work and home by encouraging employees to use their personal values in making workplace decisions. Examples of this include encouraging employees to spend the companies’ money as if it were their own, and not cutting corners on quality, and introducing ‘buddy’ programmes to help new people on board. By bridging the gap between individual and corporate values, many companies feel they will be creating more ethical workplaces.

High standards of professional conduct and competence are at the heart of good ethics in management, wherever practised in the world. Being professional means that you behave appropriately for the culture and the situation. If you are new to a culture, ask someone who has worked there before to explain a few basic norms and expectations. How you present business cards and organise business dinners is different in Shanghai from in Chicago.

Of course, some good practices are universal. You should not bully or insult others or behave in a way that could be construed as harassment of any sort. Nor should you use email in the wrong way – whether it’s to boast of your colleagues’ sexual prowess or to ask everyone on the site if they have seen the sausages you put in the staff fridge. If you’re unsure whether your behaviour is professional, ask someone for feedback, or imagine what your grandmother would say! The Confucian interpretation of the golden rule is also helpful: do not do anything to anyone else that you wouldn’t want them to do to you.13

Trust is a fundamental element of any relationship between a manager and others. It can take a long time to establish, yet only moments to destroy. Establishing a working relationship that is based on trust goes a long way to improving morale, motivation and employee engagement, which in turn leads to increased productivity and performance.

There are two sides to trust within a relationship. There can be:

- trustworthy behaviour (i.e. responding to trust others place in you);

- trusting behaviour (i.e. putting your trust in others).

Trustworthy behaviour involves:

- communicating – keeping people informed;

- keeping promises;

- being honest;

- not misleading people;

- admitting when you are wrong;

- showing concern for others;

- keeping confidences;

- not talking behind others’ backs.

What to do when you are under pressure

Limited resources, time, training, money and equipment can add to stress levels. A certain level of pressure can be effective in keeping people motivated. However, when it gets beyond this level problems often arise and stress ensues. Recognising that you are pressurised before stress takes hold will enable you to assess your activities and processes with a clear head. Try to work smarter by streamlining processes and decide how better to manage time and resources. Eliminate ‘waste’. Accept the elements that are outside your control, and work on the problems you can change.

Consider the following steps for identifying and reducing the causes of stress and pressure:

- Recognise your symptoms Health, behaviour and attitude to work.

- Identify the sources What is making you feel pressured? This could be home life as well as work life.

- Know your response Knowing how to adapt and adjust.

- Identify the strategies that help you cope Such as breaking down a work task, removing or reducing outside pressure; taking a walk; taking a holiday.

- Begin to make the necessary changes To yourself, your relationships and your activities.14

The work environment

Once upon a time, industrial estates and office parks were bleak and faceless environments, showcased in series like The Office. But thank goodness, that’s starting to change. Increasingly, office parks are trying to create environments and programmes that help managers enjoy work. One such park, near where I live, has even made ‘Enjoy Work’ its credo, equipping office park staff with sunny yellow jackets, golf carts and umbrellas emblazoned with the slogan Enjoy Work. Built around a lovely setting with a bridge, waterfall, lake and birds and fish, there are constant activities that encourage people to mingle – everything from massages and Chinese tarot to soccer games, concerts, barbecues and fireworks. Outside seating areas and temporary ‘chillax’ zones provide plenty of places for enjoying nice weather. A health club and restaurants onsite complete the vibrant atmosphere. (Note: this complex just won an award for creating a first-class work environment!)

Keeping balance

Maintaining a work–life balance, and a workload balance, will significantly help to prevent stress and burn-out. Research shows that those who experience wellbeing at work are more productive, and work–life balance is an essential part of wellbeing. Find time to relax and unwind. Improve your own efficiency in such key areas as time and energy management, avoiding information overload, and delegation.

In today’s 24 × 7 world, managers’ stress increases as they are always accessible by Smartphone or iPad. In fact, experts say that this accessibility is increasing stress levels and diminishing productivity. So don’t expect your team to answer emails at all hours. And make sure your boss has reasonable expectations. A friend of mine quit her job as company President because her boss expected her to have her phone on by her bed every morning from 6.00 a.m. and every evening till midnight. Go on. Switch It Off!

Top tips: best ideas for work–life balance

- Focus on outcomes not office time.

- Encourage your employer to adopt flexi-time and flexible working.

- Take a walk break once an hour (‘Management by Walking Around’).

- Plan your week to balance family, work and fun activities.

- Put your health and family first.

If all else fails – try a career break. I recently took three years out from corporate life to help my family, moving continents to do so. Of course it was tough to re-enter the working world, but the time spent putting my family first gave me a valuable perspective and helped to re-frame my focus when I did return.

Top tips, pitfalls and takeaways

Top tips

- Know Yourself. Know Others. Know your Style.

Top pitfalls

- Forgetting the impact of your behaviour on others and its impact on the climate, morale and performance.

- Losing balance and effectiveness through burn-out.

Top takeaway

- Style matters. How we manage others at work has the biggest impact on their job satisfaction. People leave people, not jobs.

2 http://www.washingtonpost.com/leadership

3 Jung, C.G., Psychological Types, Collected Works, Vol. 6, Princeton University Press (1971 [1921]).

4 Csikszentmihaly, M., Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Harper Perennial, 1990.

5 Blake, R. and Mouton, J., The Managerial Grid: The Key to Leadership Excellence, Houston: Gulf Publishing Co., 1964.

7 http://www.managers.org.uk/workinglife2012

8 Carolyn Foster, ‘Leading from strength: making a difference as only you can’, Google Tech Talk, 29 Jan. 2008, citing Buckingham, Marcus and Clifton, Donald O., Now, Discover Your Strengths, Free Press, 2001.

9 Ibid.

10 Authentic happiness, in Foster, ‘Leading from strength: making a difference as only you can’.

11 http://www.ethicability.org/

12 Steare, R., Ethicability, Roger Steare Consulting Limited, 2011.

13 Confucius, Analects, 43, Aspen Institute Germany Seminar Readings, 2012 edn, p. 275.

14 Stress Management: Self First, CMI Checklist Series, no. 34, 2011.