14

How to manage change

What you will learn in this chapter

- How to identify when change is needed and anticipate its impact

- How to plan the different types and steps of change

- How to implement change in your organisation

- How to help people understand the impact of change

‘Be the change you want to see.’

Mahatma Gandhi

In 2012, over nine out of ten managers experienced change programmes in their organisation,1 yet only 30 per cent said that senior managers managed change well.2 We also know that it makes employees uncomfortable, with 70 per cent of managers saying that change decreased morale in their organisations.

Here are some of the reasons changes fail:

- Fad of the day Doing it because it’s in vogue rather than because it’s right for your organisation.

- Lacking in authenticity An autocratic leader sends everyone on an empowerment course but doesn’t go – or change their own style.

- Losing sight of the end-goal Becoming so obsessed with the process you forget what the output was supposed to be, as long as it’s on time and on budget.

- Cutting costs without changing culture Saying you want to flatten things to improve decision-making but really you are just cutting costs without changing the way you work to compensate.

- Systems/user gap Spending a lot of money installing new systems but not asking users for their input or training them on how to use them correctly.

All these elements are within the control of senior managers. I have been through major organisational changes in every single company I’ve worked for, and have led them as well as been led by them. Those that actually succeeded combined the approaches discussed in this chapter.

Spotting signs of change and anticipating their impact

The first thing to do is to recognise when change is required, and why. The top five reasons in 2012, according to one study, were:

- Organisational restructuring

- Cost reduction

- Voluntary redundancy

- Culture change programmes

- Changed employee terms and conditions

Change can also happen for external reasons, like changes in legislation or markets, but the most common reasons have negative consequences for employees. These can include decreased motivation, morale, loyalty, job security and well-being. Most employees see change as forcing them to work harder, faster and longer – especially when the change is driven by cost reduction. Many managers are also sceptical: over half thought decision-making wasn’t any faster and 45 per cent said their organisations were no more flexible as a result of change – nor did the majority think that profitability or productivity had increased.3

Planning change

Most changes today are evolutionary, rather than revolutionary. And most involve strategy as well as operations, and transformation as well as transactions. For all types of change, however, you need to plan. And given that most people will have inherently negative views on change, it pays to involve them in the process.

When planning change, think about the different forces at work. There will be forces for and against the change. Try to picture these – list the top three things that are driving the change, and the top three things that will get in the way. Don’t forget behavioural issues when you are considering your change programme. Often those will be the things most difficult to change!

Plan for change in the way you would for any major programme. Cover:

- Vision What is the ‘big idea’ behind the change? What is the organisation striving to achieve? This must be clear and compelling.

- Scope What needs to change to realise the vision? What processes and departments are involved and what outputs, products and services will be different when you are done? What ways of working and attitudes need to change?

- Time frame What will change when, and in what order? Radical change takes time, especially if attitude change is involved.

- People Who will be most affected by change and how? Who will play prominent roles in implementing change (the change agents)?

- Resources How much will the change cost? Will there be offsetting benefits?

- Communications Will you need new mechanisms and structures to communicate with employees, customers, suppliers and other stakeholders?

- Training have you allowed for the training of managers and front-line employees in both hard and soft skills associated with change?

It’s best to do this in a group. Try the power brainstorming technique described earlier in Chapter 9.

exercise

Look at change programmes in your organisation. Do you understand why the change is needed? Do you have a clear change plan? Do you understand the forces that are working in favour of, as well as those that are working against the change? Make sure you and your team are comfortable with all of these elements before you proceed to implement.

Implementing change

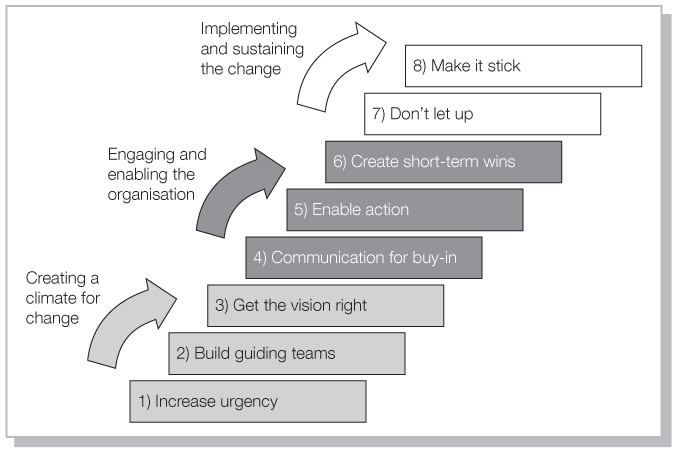

The best-known model for implementing change comes from John Kotter of the Harvard Business School. It involves an eight-step programme, illustrated in Figure 14.1, which builds on three phases: create a climate where change can occur; engage and enable your organisation; and implement and sustain the change.

Figure 14.1 Kotter’s eight-step programme for implementing change

Source: Kotter International (www.kotterinternational.com).

It is difficult in practice, although it works very well when you do it well. Most people fall down on the people aspects of change, rather than the business aspects. Here are some tips for how you can best engage people when it comes to implementing change.

Make sure you make a clear case for change that includes both business and cultural aspects. Why should you change? Are your costs growing faster than your income? Do you have a pension deficit to service? Is your business model under threat from new technologies? Thinking about tangible business reasons that everyone can grasp will help your case. But you’ll also need to think about cultural reasons. For example, if employees are not engaged, and the main reason is that they think directors don’t work together, then you can use the change to drive a more collaborative and participative culture.

The most difficult part of any change programme is convincing people of the need to do things differently. People will often take recommendations as a personal criticism, or have come to have very ingrained ways of doing things. Often people leave this task to outside consultants, but it is best owned by people within the organisation. Try getting a group together and asking them about things they do that could be done better. If the business isn’t growing, ask people what they think needs to be done differently. Most people understand that things need to change, but they are still fearful of it. Involving them lessens that.

About 80 per cent of changes involve organisational redesigns and restructurings. The best way to do this is to involve the people affected in the process, rather than leave it to HR and senior managers to draw up organisational charts behind closed doors. Even if you are making redundancies, you will get a much better organisation if you engage those who do the work in the design. Besides, it is virtually impossible for leaders to sit and design an entire organisation, from top to bottom. Involving people at the level of the changes and above in designing that part of the organisation will result in a better structure with fewer overlaps and greater ownership. Plus, involving people will help gain their commitment to the new roles, as well as stimulate their interest in applying for them.

Maximising your chances of making change successful: the change equation

Sometimes it can be helpful to consider change as an equation: C = A x B x D > X +Y

- C = the probability of change being successful

- A = the dissatisfaction with the status quo

- B = a clear statement of the desired future state

- D = concrete first steps towards achieving the desired future state

- X = the cost (not just financial) of the change

- Y = the inertia to be overcome

If you are dealing with organisations that have been doing things the same way for a long time, it may be easier to focus on B and D than on A, as it’s unlikely they will be keen to change the way things are done.

Source: Gateshead Council, Understanding and Managing Reactions to Change, 2009, p. 10

Ten tips for driving organisational and cultural change

Remember that attention to organisational design and culture (see Chapter 12) is necessary. Here are ten disciplines that help:

- Share information as widely as possible. If information is limited to top management, this will generate rumours and resentment.

- Allow for suggestions, input and differences from widespread participation. If possible have a cross-departmental representation and consultation committee.

- Break the change into manageable phases. Encourage the relevant people to be involved in each.

- Minimise surprises: make standards and requirements clear. If you don’t know the answer to something, say you don’t know. But try to say when you think you will know.

- Recognise prevalent value systems may need changing too. If people’s primary motivator is who they sit next to rather than their work contribution, try mixing things up so that everyone is sitting next to someone new.

- Expect – and deal positively with – conflict. Explain why decisions are made: even if they are not popular, most people will respect that you listened and explained.

- Create a blame-free culture of empowerment and push down decision-making – but clarify decision boundaries.

- Break down departmental barriers – make sure change teams are cross-departmental and functional. Involve many different people across the business in redesigning LEAN processes for example. Make it fun.

- Design better, more meaningful jobs, and ensure that some people are promoted internally as a result of the changes. Try to introduce popular policies like flexible working, or reward and recognition programmes alongside the new roles.

- Make sure you have a feedback system in place that monitors how well your change programme is being implemented. Celebrate every early success, and also admit it when you don’t get everything right.

The voice of the customer

‘Town hall’ type sessions that get customer-facing employees to contribute to better ways of doing things can often encourage change. In one organisation I worked in, the people manning the customer service lines knew that their time was not being well spent. They said they often spent time on the telephone with retired people who were no longer relevant for the services offered, and that they were mailing letters because we weren’t capturing email addresses. Listening to these examples informed and encouraged my grasp of the need for change by underpinning it with real examples. It also made them part of the programme. They became ‘front-line’ advocates for change.

Communicating change

This is the thing that most often goes wrong when managing change. People forget the very high and constant need for communication. It’s really not enough to announce a change programme and then expect everyone to ‘get on with it’. You will need to constantly repeat and position the reasons for change, and address people’s concerns.

Here are seven tips for managing the communication process:4

- Create a sense of urgency In a situation where employees are mistakenly feeling ‘fat and happy’ they need to be re-educated. Or when you are changing a strategy they will need to see how and why that needs to be done in order for you to keep the organisation sustainable. A shared sense of urgency comes from shared understanding of the threats as well as missed opportunities.

- Communicate the big picture Employees need to understand the business environment they are operating in. They will then understand the implications for themselves and their job and will be better equipped to make decisions. Try to link the communication to observations that employees have made themselves (see ‘The voice of the customer’ box).

- Share the thinking as openly as possible Change will not be properly implemented unless people understand why it is necessary. Commitment comes from a sense of ownership, and ownership comes from participation and engagement. Use this engagement to encourage more examples but also to raise concerns. Be as open as you can. In my experience, open change processes are much healthier than closed ones.

- Maximise the sense of continuity and stability If change is sold as ‘revolution’, employees may see it as violating their values and will resist. It helps to understand how people are feeling. What they really want is to maintain continuity where possible, and quickly re-establish equilibrium. Positioning change as evolutionary will reassure people and help the organisation retain existing strengths.

- Do not wait – communicate! Even in the most uncertain of situations, there is always something that can be communicated. Managers often mistakenly assume that they are in control of communication and can turn it on and off like a tap. Unfortunately, if management does not communicate, the grapevine will.

- Communicate probabilities and scenarios – but be honest Be truthful – don’t say no one will lose their job if it’s not true. While you cannot predict the future, you can talk about what might happen. People will speculate anyway, so you may as well give them real possibilities to think about. It is also helpful to give people a timescale of when you expect to be able to communicate specific information. This allows you to say something while you are still analysing and debating the way forward.

- Make face-to-face the main communication channel Research has shown that people prefer to receive information about change from their immediate manager, face-to-face. Line managers are often perceived as being ‘in the same boat’ as their teams. They can help their people ‘unpack’ information and link it to their own roles. If you communicate in this way, you will be better able to assess people’s concerns, correct misconceptions, gather feedback and minimise the chances of sensitive details leaking out. Combine the face-to-face with bigger sessions wherever possible so that messaging is consistent. And be sure managers are trained to emphasise the same key points in their communications.

exercise

What is your ongoing communication plan for your change? Ask people in different departments and different levels in your organisation about the change – are their answers consistent? If not, address. Also ask them to give you ideas of what’s going well, what’s going ‘OK’, and what is going badly in the change process and adjust your communication and plan accordingly.

Understanding resistance to change and the stages of change

Despite your best efforts to do everything right, you will always be faced with blockers. According to research, the way people respond to change is fairly consistent:

- 5% will champion change;

- 20% will be early adopters of it;

- 50% will adopt a ‘wait and see’ approach;

- 20% will resist until they have no choice but to change;

- 5% will never change.

The bottom 25 per cent are often referred to as the blockers or terrorists. They may actually actively try to sabotage the change efforts, or indeed pay lip service to them while undermining them in their own behaviours. Every organisation has these. When you are leading change, it is important to understand who is in which group. You will need to create a coalition of champions and early adopters at all levels. It’s important to recognise them and encourage them to be proactive, both in big groups but also back in their departments.

Equally, understanding the motivations of the wait and see types and the cynics is important. They are likely to be this way because of their own fears of disruption to the status quo. Understanding that people respond to change at different speeds is very important. The champions go through the process very quickly, while the cynics and blockers take much more time.

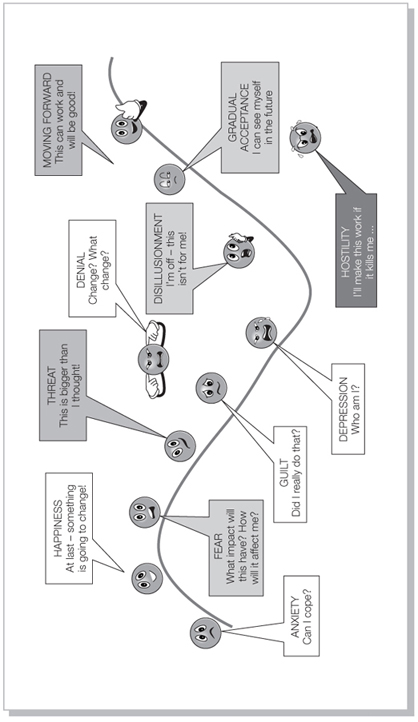

People go through common reactions and stages when dealing with change (Figure 14.2). These stages are as follows:5

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Fear

- Resignation/acceptance.

Often, the blockers and cynics will be behind the curve, to the left of the champions, who have moved very swiftly to the right. Understanding the issues people are facing at each stage of the change process will help you to manage them better.

Figure 14.2 Common reactions and stages when dealing with change

Source: From Fisher, J. M., ‘A Time for Change’, Human Resource International vol 8: 2 (2005). Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

exercise

For your area, plot out where you think everyone is on the path of change. Identify the champions and the blockers. Can you encourage the champions to help move people along and coach the blockers? If not, understand what the blockers’ concerns are and recognise how you might deal with them. Understanding and talking through their concerns will help them. By the end of the change we want people to reach a state of hope that this will be better in the future, and enthusiasm for the new way of working.

Top tips, pitfalls and takeaways

Top tips

- List the top three things that are driving the change, and the top three things that will get in the way.

- You need momentum, but don’t move too quickly. Involve people. Communicate constantly, honestly and specifically. Refer back to the consistent themes. Celebrate early successes. Get stuff wrong and correct quickly. Remember there will always be a rumour mill. Remember people value small stuff.

Top pitfalls

- Forgetting that cultural change underpins organisational and strategic change.

- Moving too fast or too slow.

- Keeping the reasons for change unclear or secret.

Top takeaways

- Most employees have negative experiences and expectations of change, but some of the key success factors are within the control of managers.

- Planning for change is a major undertaking and has to be treated as such.

1 http://www.managers.org.uk/workinglife2012, exec summary, p. 6.

2 http://www.managers.org.uk/workinglife2012, pp. 13 and 21.

3 http://www.managers.org.uk/workinglife2012, pp. 12, 13, 15.

4 Lucas, Erica, Riding the Change Roller-Coaster, Professional Manager, 2002.

5 Kübler-Ross, Elizabeth, On Death and Dying, Routledge, 1969.