10

Setting a strategy

What you will learn in this chapter

- How to identify what a strategy is and importantly what it isn’t

- How to set a strategy for your business area

- Tips for refining and improving your strategy

- How to use tools to help you set better strategies

- How to check whether your strategy is right – using stories

What is strategy?

Strategy is one of the most scary and misunderstood words in the management lexicon. People use it to confuse, threaten, condemn and otherwise torture their colleagues. It’s often used as a prelude for much complicated analysis and reams of PowerPoint slides and binders labelled ‘strictly confidential’. The truth is, strategy is a set of simple choices, and relevant, interrelated and prioritised activities based on those choices. It should be based on evidence, capability, as well as instinct. It should be short. It should be obvious, and expressed in simple language. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos has this down to a ‘t’. He doesn’t spend much time on strategy, he says, because it’s obvious. Amazon’s strategy is to offer the widest range at the lowest price and fastest delivery for every category in which they compete.1

Yet many smart people and smart companies do not understand this. I have participated in numerous strategic planning sessions that have produced tons of initiatives and charts and resulted in something that was too difficult to understand or communicate. I once sat in a day-long board meeting discussing a strategic plan we had worked on for weeks. At the end of the session, one of the newer non-executive directors, asked: ‘Maybe I’m missing something, but what exactly is the strategy here? All I’ve heard is a long list of initiatives from categories and geographies that don’t join up.’ She was right.

Equally, sometimes people misjudge obvious strategies because they are looking for something ‘deeper’ or ‘hidden’. For me, a clear example concerned a misunderstanding by analysts and business journalists of the decisions of Marjorie Scardino, the former CEO of the FT parent company Pearson. She had declared that sale of the Financial Times would only occur ‘over her dead body’. When she stepped down, commentators began clamouring for its sale, arguing that it didn’t fit the company strategy. Yet the mission of the company is to become the number one learning company globally, for people throughout their lives. As one of the most trusted brands in business education, the FT is a natural asset. The strategy had been logical and Scardino’s decisions supported it.

There are two more essential rules of successful strategies. These are perhaps the most important of all:

- No one ever sees the strategy – only the execution.

- Operational excellence is not a strategy.

Many companies flourish for a long time because they are operationally excellent, even if they don’t have clear strategies. Other companies perish, even though they had clear strategies, because they couldn’t execute them well; this is the more common.2 Here are two opposite examples to illustrate the points.

case study

Good strategy, shame about the execution

Company A was a very successful health and beauty retailer, which had diversified into clothing, food and other areas. The margins on health and beauty were good, so the chain decided to refocus on health and beauty retailing, and to add value by branching out into services, such as beauty care, massage, acupuncture and dentistry. Over thirty different new businesses were launched over two years, each fully staffed with marketing, operations, and so on, as well as a managing director. There were no test markets or milestones that were clearly defined. Executives became uneasy about admitting that they weren’t successfully executing the strategy. Long leases were signed, millions were spent on purchasing equipment and expensive staff were hired with advanced health qualifications. All before any business model was proven. The net result? £300 million of shareholder money was spent with no return. The CEO lost his job, and all the new businesses were shut down.

Operational excellence is not a strategy

Once there was a very successful company that sold telephone directories. It was extremely well run and twice won awards for operational excellence. It had successfully expanded into the US and UK. It had also entered the digital and mobile market places with new directory services. The internet began growing much more quickly than the print-based directory services. However, because the company had such operational excellence in sales and distribution of directories, it was reluctant to embrace the internet quickly. Also, because the internet offered such great untapped capabilities, the executives running it were reluctant to be associated with the directories and wanted their own sales forces, marketing, routes to market and product lines. Separate divisions were maintained; there was no integration and no cross-media platforms. The board decided to spend £2 billion buying more directory businesses rather than invest heavily in the internet or mobile. Today, the stock has been as low as 3p, the board and brand names have changed and the company is going bankrupt, with the banks swapping debt for equity.

- A simple clear set of choices.

- An integrated, relevant set of activities based on those choices.

- Obvious to everyone – you can tell it like a story.

- Based on evidence, instinct and capability.

- Something that constantly helps steer your business and organisation.

- Evolving to new market and environmental conditions.

What strategy isn’t:

- A headache.

- Death by PowerPoint, numbers, or binders.

- Too complicated, obscure, and/or not easily articulated in a story.

- A series of plans, initiatives, targets and budgets.

- A substitute for execution (but then nor is great execution a substitute for strategy).

Strategic storytelling3

This is a story that Herb Kelleher – one of the founders of Southwest Airlines in the United States and its former CEO and Chairman – used to tell as he visited his operations. He would say:

It’s funny; I get letters all the time from shareholders, and they’re often angry letters. They say ‘America West is flying between Los Angeles and Las Vegas for $149 one way and you, Herb Kelleher at Southwest, are pricing $79 for that same one-way ticket. Don’t you have the decency to at least kick your price up to $129? Why are you leaving so much on the table?’

Well, what I do is write back and reply, Thank you so much for your letter. However, you don’t really understand who we are, and you really don’t understand who our competition is. It’s the automobile; it’s not other airlines. And $79 is the price to drive, including maintenance, insurance and gasoline, from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. That’s how we price our tickets.

He would use that simple story to drive home what in many ways could be seen as the entire strategy of the organisation, vis-à-vis its competition. It was done in such a way that everyone at Southwest knew who the competitors were and why that ticket was priced the way it was.

So what makes an effective story?4 Douglas Ready has come up with the following elements. Effective stories are:

- context-specific;

- level appropriate;

- told by respective role models;

- have drama;

- have a high learning value.

More strategic stories

Punica

My first brand was Punica. This was a watery fruit drink – only 20–29% fruit juice. The rest was water. And many of the flavours were sugar free, sweetened with artificial sweetener. My first boss asked me to go away and write an analysis of the brand. I noticed that the segments Punica was in were growing – fruit-based drinks and sugar-free drinks; and it was sold in crates of six 1-litre returnable bottles alongside other soft drinks. But Punica had been promoted as a fruit drink, as it was perceived as a watery orange juice. Because of the wide- mouth 1-litre bottle, the low fruit-juice content, and being sugar free, Punica was a great thirst quencher. So we decided to reposition it as a premium soft drink rather than as a cheap orange juice. We needed to reframe the competitive set away from fruit drinks and towards sodas. We needed to complete the following: Like soft drinks, Punica is _____. Better than soft drinks, Punica is ______. We filled in the blanks thus: Like soft drinks, Punica quenches thirst. Better than soft drinks, Punica is full of fruit and sugar free. Sales doubled, it became a major success in Germany and was ultimately sold to Pepsi.

Always

Women could either use thin sanitary pads that were more comfortable but often failed, or they could wear thick pads that were uncomfortable but more absorbent, so didn’t fail. Always Ultra solved this trade off. A 1mm thin pad that absorbed like a thick pad. The problem was that women didn’t believe it. So we needed to turn the rules of the category upside-down to convince them. Instead of subtle imagery we did side-by-side product demos, and showed testimonials of ordinary women amazed at its powers. We sent out samples to over 400 million women in Europe, and even put a cut-out piece of a real pad in the leaflet inviting women to do their own demo at home. It worked, and Always became the market leader everywhere it launched in Europe in Year 1.

Whiskas pouches

The strategy for years had been to expand canned pet food in grocery. One of the owners had a favourite slogan: the profit is in the can. Canned pet food was sold at a premium, but contained a lot of water. Meanwhile, Mars had invented something that had less water, and was much easier to use and store than a can. It was a single-serve pouch, superior in taste, convenient, profitable – and also unique to Mars. So the strategy had to be to convert the market from cans to these new pouches. How to get people to switch? Convince the owners that their cats, notoriously finicky animals, preferred the taste of new pouches to the best of cans. This meant giving away samples and having cat owners compare Whiskas pouches to Whiskas cans. So we did. And Whiskas gained 12 share points.

Six tools to help you develop strategy

1. SWOT

This classic tool stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats. It’s a useful way of summarising information. But it’s not a strategy. It’s more like a frame of reference.

2. Michael Porter’s Five Strategic Forces

Working in the 1980s, Michael Porter identified five factors affecting the competitive position of a company. He argued that a company that wishes to improve its performance must take account of these five forces, before it can make a decision as to the best strategy for future success. The five forces identified by Porter are:

- The entry into the market of new competitors.

- The threat of substitutes – similar competing products.

- The bargaining power of buyers or customers.

- The bargaining power of suppliers.

- The level of competition from existing competitors.5

Porter’s model is designed to help companies choose the most promising strategy for their business. It does this by focusing attention on the competitive forces at work in the wider industry scene, not just the company’s internal resources and operational efficiency. In the 1980s, Porter identified three generic strategies: competing on price, differentiating products and services by offering something not offered by competitors, or focusing on a niche market; later he went on to consider the role of diversification and the impact of the internet. But he stresses that it is not enough just to gather information. Companies need to ask themselves how they can use competitive forces to their advantage and rewrite the rules of the industry.

3. The Four Cs

- What is your unique value to Consumers?

- Advantage over Competitors?

- Advantage for Customers or those who distribute or sell your products and services?

- How does your strategy reinforce your Company’s core strengths and competencies?

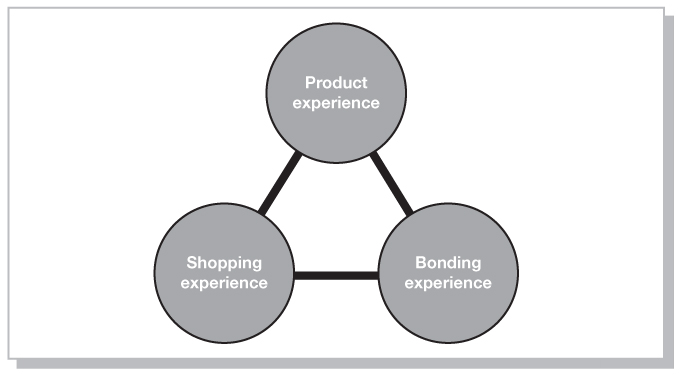

Figure 10.1 The activity system

4. Activity system

This was developed by Michael Porter of Monitor Consulting and used by a lot of companies.

All customers relate to your product in three ways (see Figure 10.1). They have a bonding experience with your brand based on how you communicate with them. They have a product or service experience of your offer. And they have a procurement, or shopping experience of how they get your offer. The trick is to come up with a set of activities that reinforces your unique proposition across the bonding, product and shopping experiences. Often, if you can reinforce these, you will develop an unassailable competitive position. IKEA does this really well – see an example on p. 132. So do Net a Porter, Lego and Starwood.

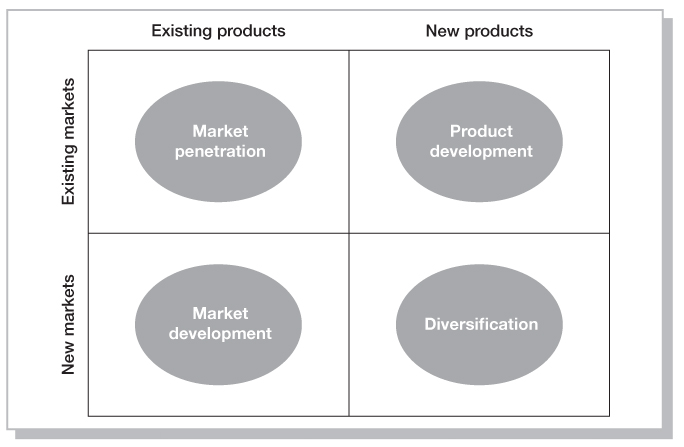

5. The Ansoff matrix

It is helpful to prioritise and class innovations and strategies with regard to new markets and new products versus existing ones. Remember it’s always hardest to go for new products and new markets simultaneously.

6. One-page strategy picture

A boss of mine at Mars used this – I think he and some others made it up. It’s a great tool for keeping strategy simple. See Chapter 11.

Figure 10.2 The Ansoff matrix

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission of Harvard Business Review, from ‘Strategies of Diversification’ by Ansoff, I., 1957. Copyright © 1957 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.

Six tips

- Solve a trade-off This can very often result in a breakthrough strategy, one where you will create a new category. Like Always Ultra, or Spanx or concierge services for busy professionals – or even Wal-Mart, which tries to help you to save money and live better at the same time.

- Redefine your competitive set Like Punica or Southwest Airlines (see above).

- Come up with a new creative use for something The weak glue that should have been a failure at 3M became the Post-It note. All because someone noticed that people were using the weak glue to mark up files.

- Don’t forget to do a business review Look at the four Cs, look at your customers, competitors, market and environment. What is it telling you in your gut? Also, what do you need to watch out for? And do you have the right capabilities to execute? If not, how will you get those?

- Invent a new category Invent an iPod or iPad rather than just another mobile or PC.

- Have a strategy day Often those in the company will have a tacit knowledge of what strategic direction they need to follow. Bring it out using a ‘power brainstorming’ approach to collective problem solving (see Chapter 9).

At P&G I was lucky enough to work with A.G. Lafley. He was and still is a great strategist. While I was writing this chapter, his new book came out, co-authored with Roger Martin.6 What they have to say on strategy is priceless: I am reprinting Martin’s blog7 here.

I must have heard the words ‘we need to create a strategic plan’ at least an order of magnitude more times than I have heard ‘we need to create a strategy’. This is because most people see strategy as an exercise in producing a planning document. In this conception, strategy is manifested as a long list of initiatives with timeframes associated and resources assigned. Somewhat intriguingly, at least to me, the initiatives are themselves often called ‘strategies’. That is, each different initiative is a strategy and the plan is an organized list of the strategies. But how does a strategic plan of this sort differ from a budget? Many people with whom I work find it hard to distinguish between the two and wonder why a company needs to have both. And I think they are right to wonder. The vast majority of strategic plans that I have seen over 30 years of working in the strategy realm are simply budgets with lots of explanatory words attached . . . . To make strategy more interesting – and different from a budget – we need to break free of this obsession with planning. Strategy is not planning – it is the making of an integrated set of choices that collectively position the firm in its industry so as to create sustainable advantage relative to competition and deliver superior financial returns. I find that once this is made clear to line managers they recognize that strategy is not just fancily-worded budgeting and they get much more interested in it . . . . That strategy is a singular thing; there is one strategy for a given business – not a set of strategies. It is one integrated set of choices: what is our winning aspiration; where will we play; how will we win; what capabilities need to be in place; and what management systems must be instituted? That strategy tells you what initiatives actually make sense and are likely to produce the result you actually want. Such a strategy actually makes planning easy . . . . This conception of strategy also helps define the length of your strategic plan. The five questions can easily be answered on one page and if they take more than five pages (i.e. one page per question) then your strategy is probably morphing unhelpfully into a more classical strategic plan . . . .

So if you pass the five-page mark it is time to ask: Are we answering the five key questions or are we doing something else and calling it strategy? If it is the latter: eject, eject!

Source: Roger Martin, ‘Don’t confuse strategy with planning’ (HBR Blog Network, 5 February 2013). Roger Martin (www.rogerlmartin.com) is the Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto in Canada. He is the co-author of Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works.

Lafley, A. G and Martin, R., Playing To Win: How Strategy Really Works, Harvard University Press, 2013.

Top tips, pitfalls and takeaways

Top tips

- If strategy is difficult to communicate clearly, it’s probably not well thought-through, or not really a strategy.

- Try to put your strategy on one page, using the example here – or another one.

- A SWOT analysis and Michael Porter’s five forces remain useful tools for deciding strategy.

Top pitfalls

- It is still common to have a good strategy, but be let down by poor execution.

- Lots of plans with budgets attached do not constitute a strategy.

- Don’t overcomplicate it!

- It’s no use having a strategy that no one understands or is tucked away in a binder marked ‘strictly confidential’.

Top takeaways

- Strategy is about clarity of the positioning of a company’s services. It should be simple, and clearly communicated.

- Strategies are more likely to fail because of poor implementation than because of poor concept.

- Strategic choice is essential, however; operational excellence is sometimes not enough as it could be in a dying business sector.

1 Kevin Roberts, 2013 talk at P&G reunion.

2 Centre for Creative Leadership, Leadership at the Peak Mars training course, 2001.

3 Conger, Jay, ‘The impact of strategic storytelling’, http://edls.com/50lessonsdemo/edls/433_ProfessorJayConger_TheImpactOfStrategicStorytelling.pdf

4 Ready, Douglas, ‘How storytelling builds next-generation leaders’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Summer 2002, Vol. 43, Issue 4, pp. 63–9.

5 Porter’s Five Forces, CMI Management Model.

6 Lafley, A.G. and Martin, Roger L., Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, Harvard Business Review Press, 2013.

7 http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2013/02/dont_let_strategy_become_plann.html