16

Managing stakeholders, with customers at the centre

What you will learn in this chapter

- To understand the importance of managing all stakeholders

- To become more customer-focused in your organisation and strategy

- To understand the importance of customer insight, value and segmentation

- To treat suppliers as partners to increase value and quality

- To grasp the basics of better buying

- To identify different stakeholders and understand why they’re important

- To use simple techniques to help analyse and manage stakeholders

- To encourage collaborative partnerships and other strategic alliances

‘The consumer is the boss.’

A.G. Lafley

Successful companies, and successful managers, adapt continually. They have an understanding of the contribution of all stakeholders – and, moreover, they continually monitor and manage their relationships with key stakeholders. This chapter explains how this discipline is essential for effective change management, with a deliberate emphasis on the ultimate stakeholder: the customer.

A ‘stakeholder’ is anyone who is affected by your work. Stakeholder management is therefore essential, but it must retain a commercial focus, and not become simply an end in itself. I once held a performance review with a member of my team who was responsible for stakeholder management. When I asked him what he’d accomplished, he proudly told me that he was in forty conversations with stakeholders. When I asked him what the outcomes and objectives of these ‘conversations’ were, he looked at me blankly. He hadn’t really thought about that bit. So, I mused, I’m paying you £2,000 per conversation? We ended up making his position redundant.

At the other end of the scale, failing to manage stakeholder relationships can be disastrous. I recall when the environmental debate started happening on disposable diapers (nappies in the UK) when I was a young brand assistant. Suddenly, there was a European-wide call for a boycott and many key environmental and women’s groups were saying that the bleach used represented a health risk. Prior to this, P&G had been largely reactive to such pressure groups. Following this incident the company began to engage with them. We switched the formulae to unbleached pulp, and began dialogues and environmental projects and partnerships. Pampers survived this difficult period. Another manufacturer that refused to engage with these stakeholders ended up going bankrupt. The concept of ‘critical friend’ – of engaging with people who have very different, often opposing views and values, regularly inviting them to critique policy and practice, and acting on their observations – is now a common practice in multinational firms.

Identifying different stakeholders

As a stakeholder is anyone who is affected by your work, it can end up being many people. There are the obvious ones – your boss, your employees, your colleagues, your customers and your suppliers. But there are also many more removed external stakeholders. These include shareholders, investors, lenders, government groups, activist groups, partners, the media, volunteers, donors, trade associations, unions, national interest groups and the local community.

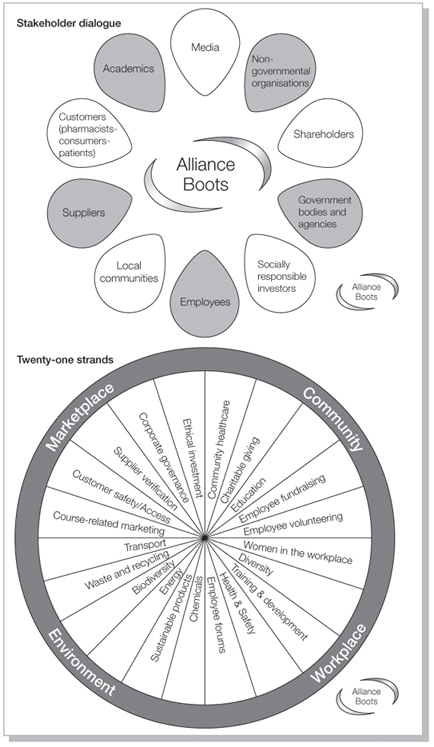

Sometimes it helps to show stakeholders in a diagram (figure 16.1). You can then map out how you will approach them for certain activities such as CSR. Alliance Boots, which has an outstanding CSR programme, uses this method very successfully. It uses stakeholder mapping to identify twenty-one different CSR work streams across the four major CSR areas of community, workplace, marketplace and environment. It then sets up programmes, sponsors and quarterly KPIs for each. One of the reasons it is so successful is that delivering CSR for stakeholders is everyone’s job – not just the CSR department! Figure 16.1 shows Alliance Boots’ approach to stakeholders, stakeholder mapping and CSR work streams.

Figure 16.1 Stakeholder mapping

Source: Richard Ellis, Corporate CSR Director, Alliance Boots, used by permission.

Managing stakeholders

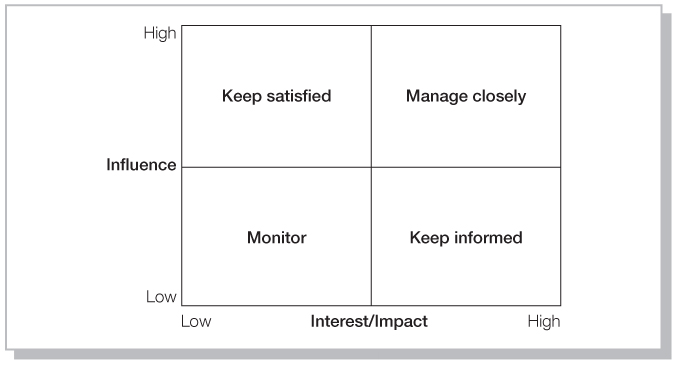

Once you have identified who your stakeholders are, it is important to analyse their relative positions and understand how best to engage with them. One widely used way of doing this is to group stakeholders according to their degree of interest in your project or work, and their degree of influence over your project or work. This matrix also gives you the main strategic challenge of how to manage the various stakeholders. For example, those who hold a lot of influence over your work and have a high degree of interest in it are the stakeholders you need to manage closely (see Figure 16.2).

Figure 16.2 Matrix for managing the various shareholders

Source: Cambridge Technology Partners (CTP).

- High Interest, High Influence These are the ones you need to manage closely and ensure they are onboard, engaged and supportive. Frequent involvement and communication with them, as well as reflecting their needs, is important.

- High Interest, Low Influence These people can be very useful advisers as they have a good degree of knowledge and are likely to give honest opinions and help, as they have little influence over outcomes. You should consult regularly with them.

- High Influence, Low Interest These people can be important in helping to win over others as they have influence, but they aren’t particularly interested and are therefore viewed as non-biased. They make good ambassadors in the external world as they are likely to be well connected. Keep them informed, but not overly so, as they aren’t that into you.

- Low Influence, Low Interest Keep abreast of their activities, but don’t over-communicate or over-manage them. However, if they suddenly target your project or work, their influence could change, rapidly, so don’t ignore them.

exercise

Map the stakeholders you identified in the first exercise on this matrix. What does it tell you about how you should be approaching different stakeholders?

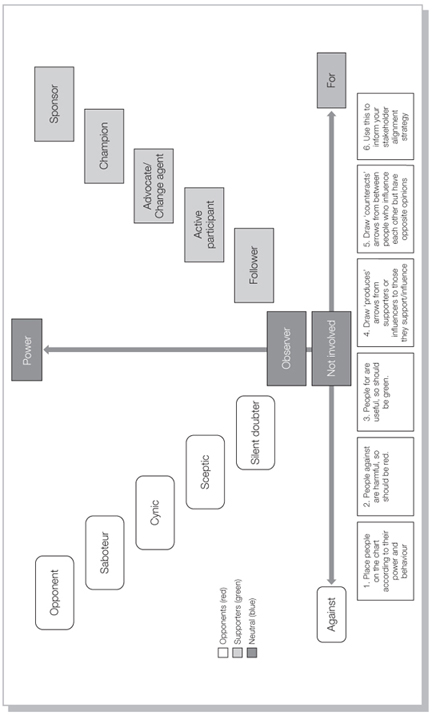

Once you’ve identified and mapped your stakeholders you need to figure out where they stand on your work. Label your supporters in green and your opponents in red. Put the neutral ones in blue. You’ll end up with a map that looks like Figure 16.3 (called the Southbeach Notation Model).

Figure 16.3 Stakeholder map

Source: Adapted from the Southbeach Notation Model (www.southbeachinc.com).

Ask yourself: how can you engage your sponsor to help gain broader support for your work? How can advocates and champions be used to successfully lobby others who may be opposed? Who influences your opponents and cynics? How can you work with them to ensure they have good information about your work? How can you manage opposition to your proposal if you cannot win them around to support your work? How can you limit or prevent the impact of saboteurs?

For each of the main stakeholder groups, set a plan to manage them. Assign a member of your team to be responsible for keeping them informed. If all of this sounds incredibly calculated and political, that’s because it is! It’s part of management.

The fundamental principles of stakeholder management concern anticipation, understanding and then engagement with people who will be affected by your work – beyond the obvious ones. Being taken by surprise by disappointed stakeholders can stymie the best of plans.

The ultimate stakeholder: becoming a customer-centric organisation

Most organisations claim they put their customer at the heart of what they do. In my executive career, I have often been surprised at how little many businesses, including large successful firms, have understood about their customers. I have often had to lobby hard to create customer intelligence functions. Many senior executives comment that the sales force’s feedback is enough for them, alongside financial metrics. But the best success stories include an understanding of the customer, linked to strategy development.

There are three elements of a customer-driven strategy: understanding the customer; responsiveness to customer needs; and value for money. Customer strategy should be linked to competitor strategy: Why might they prefer your company or service?

This focus on the customer will require time and effort, as well as financial investment. But remember that being a customer-focused organisation is almost always the key to success.

Who owns the customer?

Everyone throughout your organisation needs to take responsibility for the customer experience. But what does this mean? In many organisations, departments are based on products, technologies, business units, geographies or other internal needs of the organisation, rather than the external needs of the customer. A customer-led organisation:

- encourages boundary spanning efforts and cooperation – reward staff for cooperating between departments and creating customer-centric solutions;

- makes sure that people in departments such as accounts or HR which are not normally customer-facing get to interact with customers;

- invests in training that aims to break through silos and gives people information on different kinds of customers rather than just product-based training. Trains sales people how to recognise and ‘spot’ different customer types;

- joins forces with suppliers or other companies to share information or offer higher-value propositions for certain desirable customer groups that will engender loyalty;

- restructures the organisation with the customer in mind, sweeping away traditional silos.1 Consider organising your business by customer segment.

If you and your colleagues engage with customers it is much easier to value their importance than it is if they remain abstract invoices or research reports. Customer engagement is everyone’s responsibility, and it is now a lot easier to do with online tools.

The following actions are good starting points:

- Hold a customer engagement summit This should involve people at all levels of the organisation. Unilever India did this, requiring everyone in the organisation to spend 50 hours with customers, put their ideas in a database and then discuss how to act on them.2

- Create a customer engagement council This should act as an ongoing forum for focusing the attention of management on customer engagement. At Yell, such a body reduced customer complaints by 70 per cent over 18 months.

- Create a listening centre You can monitor, and respond, where appropriate. At O2, the CEO met with customer-facing call centre staff weekly to hear directly what customers were saying.

Customer insight and value

Customer insight means that you understand who your customers are, how they behave, and increasingly why they behave as they do. It consists of both qualitative and quantitative intelligence. It is also in some degree predictive as well as prescriptive: good customer insight helps to understand and define customer patterns so that you can better predict how they will behave, what will influence their behaviour, and how you might get them to change their behaviour in your favour.

There are many different ways you can increase your customer insight. Start by understanding the basics.

exercise

Try analysing your customer data with your sales transactions to understand the following:

- Who are your customers?

- How many do you have?

- Is your customer base growing or declining?

- How many do you gain each year?

- Lose each year?

- What is the retention rate?

- What is the average revenue per customer?

- Is it growing?

Repeat the analysis by product line and geography. Then look at the data by product, by industry sector, by size of customer. Identify those who buy more than one product. You will see some behaviours emerging.

It is very likely the behaviours will look like this:

- If your total customer numbers aren’t growing, you may be losing more customers out the back door, who are more valuable, than you are gaining through the front door.

- Your retention rates and average spends will improve the more products customers purchase from you – retention will be up to 10 points higher and customers will spend up to 10 times more!

- You will have a small number of high-value customers and a large number of low-value customers. Typically the high-value customers will buy more than one product, may buy in more than one geography, and will be with you longer.

- There will be certain industry sectors where you are more popular than others – the top three may be over half your business; equally, other metrics such as size of business or location may be important as drivers of customer value.

- Products will also have differing take-ups, values and retention rates, with many likely to be very low.

There are likely to be some uncomfortable truths when you delve into customer data. At least one ‘sacred cow’ will be challenged. That’s why the trick is to make it look and feel as simple as possible. Even if the underlying data is complicated – the insight shouldn’t be! In fact, insights need to be actionable as well as relevant. It’s best to overlay any quantitative data with stories about the relevant customer groups.

Once you have customer intelligence, certain patterns emerge. Finding real-life stories can help to uncover the potential meaning and use for your insights. Many organisations are very sophisticated at using customer insights well – P&G, Tesco and O2, for example:

- Tesco Clubcard Tesco former CEO Terry Leahy rightly credits Tesco’s Clubcard for its meteoric rise from also-ran UK supermarket to global retailing powerhouse. Tesco collected, analysed and gained insights from their customer database, so that they were able to understand and influence customer behaviour to guide their stores’ selection and managers’ behaviours. If you are a regular online shopper and suddenly stop, they will send you a huge incentive to rejoin.

- O2 Customer Reward Mobile phone companies typically focused on acquisition rather than retention. O2 realised this and rewarded customers for staying, building their affinity for the brand and identifying customers who might lapse and preventing them from doing so. It was a bold gamble that paid off, as they gained up to sixty times more in value by not losing the customers than they spent in rewarding their loyalty.3

- P&G Says P&G North American President Melanie Healey: ‘Our mantra in North America is “just one more and a healthy core”. If I take the 8 to 9 per cent of households in North America that have 10 or 11 P&G brands, what if I got the 8 to 9 per cent to 10 to 11 per cent or I got that 10 or 11 brands to grow to 12 to 13 brands in those households? That “just one more” is equivalent to about $7 billon in growth.’4

exercise

Come up with similar examples from businesses and organisations you know that have grown by focusing on customer value. Use these to convince your team and boss to do the same.

Customer lifetime value

Collecting the right kind of customer insight will help you calculate a key metric – customer lifetime value. There are different ways to calculate this, but all are aimed at helping you decide how much resource to devote to each customer. Customer lifetime value should be a key consideration in your acquisition and retention strategies (see below).

A great example concerns the Pampers brand. Pampers invests a lot of time and money reaching mothers in hospitals. Although the Pampers hospital product might not make money in itself, it introduces the brand to mothers in an environment they trust, at a time when they are prone to accepting advice. Similarly, banks target students, as once bank accounts are chosen, consumers are often sluggish about switching. All these companies typically have sophisticated means for tracking when customers are likely to switch. Other measures are valuable. The extra business certain customers give you via referrals may be worth more than the customer lifetime value of some of your most prized clients. Using a ‘Net Promoter Score’ (discussed in Chapter 13) will help you to define your brand advocates.

In recent years, many companies have invested a significant amount in customer relationship management (CRM) marketing and systems. It can go wrong, however.

Specifically:

- Poor use of CRM systems can lead to targeting the wrong customers or driving people away with over-done marketing campaigns.

- There is a limit to the amount of sophistication that CRM databases can provide – and they are often not used correctly, leading to ‘bad data’.

- Are customer relationships in themselves worthwhile? Manage customer value not relationship; sometimes CRM can become an excuse to do the latter with very little impact on the former.

It is perhaps the last point which is the most important. Whilst it is true that there are a number of examples of businesses which rely upon close relationships with their customers, equally, there are a large number of organisations where a strong relationship per se with the customer does not lead to better customer retention or sales. For example, supermarket shoppers are likely to be far more interested in price, selection and a convenient location than developing a ‘good relationship’ with a superstore. 5

The net lesson here is focus on managing your customer value and not just your customer relationship.

Customer acquisition, retention and segmentation

Many businesses spend too much time and money acquiring new customers and not enough retaining existing customers. Obviously new firms have to acquire many customers, but it is important to remember that it is usually cheaper to retain a customer than acquire a new one. There are several advantages:

- Lower customer management costs over time.

- Purchases increasing in value as the customer buys more from you over time – and becomes less price sensitive.

- Higher retention rates and more recommendations.6

Often, up to 75 per cent of marketing budgets are earmarked for customer acquisition. Try reversing this and spend 75 per cent on retention.7 Many organisations also neglect cross-selling opportunities. If you understand your customer needs you can identify related products they will benefit from. You can see examples of this in the insurance market, where companies who give you car insurance are more than happy to discount their home insurance offer to you.

It is also important to think about different customer groups and how you target and message them. For example, two customers are buying management and leadership training. One is a managing director of a small business; another is a university student studying business. Their reasons for purchase, and expectations, will be very different. Your efforts should be based on the customers’ perspective rather than your own internal perspective. In other words, don’t make it about you, make it about them.

Don’t over-complicate. When I was at Yell we focused on three groups – gold, silver and bronze, based on the return on investment certain customers got from their ads in the directory. At Mars, we created three segments which looked at the relationship between the pet and the owner as a determinant of feeding habits and positioned our brands accordingly. Keep the number of segments to a minimum – three to five is about right.

Sometimes you define segments in terms of where you want to gain business. Often it will help to target a group of users with a specific message to encourage them to switch – this is what happens when you buy one brand at the grocery store and they give you a coupon for money off a competitive brand.

exercise

Who are your key customer segments? How do you tailor your message and benefits to meet their needs? Who are your key future customers? What might you need to do to encourage them to become users of your product or service?

Suppliers

In a similar way to customer management, when suppliers are treated as partners they can also become important assets, whereas managing suppliers solely to get the best price can lead to highly negative consequences.

Begin with one particular supplier with whom you already have a good relationship, or an emerging, forward-looking supplier. Identify a partnering champion within your organisation – someone at senior level who will become responsible for laying the foundation of the partnership and making it work in the start-up phase. Partnerships allow organisations to work together to take advantage of market opportunities and to respond to customer needs more effectively than they could in isolation. Partnering means:

- sharing risk with others and trusting them to act in joint best interests;

- a ‘strategic fit’ between partners so that objectives match and action plans show synergy;

- finding complementary skills, competences and resources in partners;

- sharing information which may previously have been considered privileged or confidential;

- involving suppliers at the earliest stages in the design of a new product;

- inviting participation to improve relationships and find mutual cost benefits;

- encouraging partners to put forward ideas that will benefit both parties.

You could also consider starting a supply-chain network. This involves broadening these partnerships to include your suppliers’ suppliers and your customers. Take a look at your supply chain. Are there any areas of waste or duplication? Are there any steps you can simplify or that aren’t necessary?

Do not forget that everyone in the supply chain needs to generate profits in order to sustain their businesses. Exercising pressure on suppliers to reduce prices, rather than seeking to share the gains of cost reduction, can ultimately be counter-productive (indeed, many blame the horsemeat scandal in Europe on relentless pressure on suppliers to cut corners on cost).

Gaining real commitment from all members of the supply chain means that total costs can be kept to a minimum to the benefit of everyone. Trust takes time to develop and can be quickly lost, but it is worth it. This is especially true as more supply chains are becoming transparent, and more customers are concerned that their product’s supply chains are safe, ethical and sustainable. (There is an app that scans a code and immediately reveals whether a supply chain measures up to these criteria or whether there are gaps.)

Measuring supplier quality

It is important to monitor the quality of your suppliers. There is an almost infinite number of ways of doing this, but some of the most common are:

- Inspection – whilst this is not a value-added activity, it is a useful and basic way of gauging quality.

- Statistical quality control – this is based upon sampling and saves time and money which would go on inspecting every single item or product.

- Six Sigma – this is a way of improving the satisfaction of customers by reducing defects. The main method used is Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve and Control (DMAIC), which employs a number of statistical tools, with the overall aim of driving up quality.8

There are a huge number of quality control methods, and the one most suitable for your organisation will vary according to a number of factors, such as organisation size. Remember, if you don’t monitor the value and quality in your supply chain you may be exposing yourself to significant risk – as the recent horsemeat scandal in Europe demonstrated.

Of course, you also need to buy well from your suppliers. In order to facilitate better buying, make sure you understand your own organisation – what is important to each department in terms of the supply of goods and services? Compile a purchase history, and use this to become a proactive buyer. A clear understanding of the purchase history will enable you to negotiate better deals with suppliers by giving them an indication of the volumes they can expect over the year.

Also, understand the number of suppliers you have in a given area. I once had more marketing services suppliers than people in the marketing department! Obviously this wasn’t very efficient or effective.

Here are four tips:

- Evaluate potential suppliers by finding out what you can about them, such as their turnover and profitability and who their major customers are.

- Maintain good relationships with suppliers. Keep meetings rather than constantly rescheduling. If you have budget limits, share them.

- Compare them with competitors. Try to get at least three quotes for every major purchase decision. You’ll be surprised at how much costs vary. But compare offers carefully, as the cheapest is not always the best.

- Finally, keep records. It may be that your auditors will need to see transactions. This is especially important in light of the recent legislation in many countries on bribery.9

Strategic alliance and partnerships

The rise of the internet and the democracy of information have made collaborating much easier, and more international. It is redefining how companies work together. This has given rise to the concept of the ‘frenemy’ – an enemy with whom you collaborate. A great example is Amazon and authors. Whilst Amazon has often been referred to as the enemy of book publishers, it has, through Kindle, enabled authors to bypass publishers and self publish. Ditto Apple and apps, or You Tube and music. Open source technologies mean it is easier than ever to collaborate. So how can you take advantage of the new age of collaboration?

Identifying potential partners

Use the stakeholder exercise described earlier. Those with high interest and high influence are likely to be sources of strategic partners for your organisation or project. Consider, too, if there is a way of empowering those with high interest but low influence by giving them more power. A great example of this was P&G opening up innovation to external partners through establishing a ‘Connect & Develop’ function. Crowd sourcing is also a way of enabling individuals interested in a given development to band together and fund good ideas. Sites like Kick-starter are growing in influence and have funded new ventures. Finally, partnering with small independent retailers and giving them more clout has been fundamental to the success of sites like Zulily, notonthehighstreet.com and Tsonga.com. All of these bypass normal business models to offer products and services direct to customers.

Equally, industries banding together and working side by side have established new and more collaborative ways of working. Silicon Roundabout in London is a famous example. Some 800 technology start-ups exist side by side, sharing problems and supporting each other. They have attracted £50 million in funding from the government to build more public spaces in the area. The innovation is fuelled by informal encounters over coffee, where a chance interaction can lead to deals being done, or productive business relationships. There is a sense of community, and people will often share approaches to problems rather than keep things secret. Such informality can lead to a highly creative environment.

exercise

Using your stakeholder map above, identify potential partners for your key project from a set of potential competitors or opponents. Understand their motivations and how best to approach them. Then make a plan to do so, to see if you could partner in a way that’s beneficial to you both.

Managing the Board of Directors

One of the stakeholder groups many managers know least about is their board of directors. Boards are there for fundamentally two reasons: one is governance, and the other is guidance, also known as stewardship. Governance is about ensuring the company complies with principles of how it is run, is well-managed, legal and ethical and has a good approach to risk management. Guidance, or stewardship, is about offering support and encouraging ideas, as well as challenging assumptions to bring out the best thinking. Run by the Chairman, the best boards offer both. What they don’t do is management.

Boards typically meet between six and twelve times per year for a day. Directors are not hands-on and will not know the day-to-day details – nor should they. However they will usually be asked to approve strategy as well as major investment decisions such as new capital programmes or takeovers.

Therefore, if you are asked to present to the board, or need to attend board meetings, here are some tips.

- Recognise the board’s role is governance and stewardship.

- Decide if your presentation is addressing one or the other and craft it accordingly. Always clear the presentation with your executive colleagues – don’t surprise them at the board.

- Ask for input and expect questions, guidance and advice. Make sure you can give the reasons for your view and that they are documented and well founded.

- Don’t draw the board down into detail and endless papers. Make sure you stick to the relevant risk you are describing or the overarching decision, or advice you need.

- Be professional and discreet. It’s not the best idea to divulge what you think about everyone to a board member. That said, they can offer great insights into the thinking of the CEO.

I once learned from a non-executive director that the CEO was thinking of getting rid of my role. While it didn’t prevent him from doing so, at least it gave me a ‘heads up’!

Top tips, pitfalls and takeaways

Top tips

- Have a plan for every stakeholder group; it’s not political, it’s part of management.

- Draw up a stakeholder matrix, plotting interest against degree of influence, and use it to shape your stakeholder management.

- Take the trouble to understand customer value, not just customer relationships – in some sectors, the ‘relationship’ is never going to be deep.

- Create a listening centre and a customer engagement council.

- Maintain continual attention to the quality of suppliers.

- Maintain real engagement with the supply chain – this can result in savings and benefits for everyone, including customers.

Top pitfalls

- Too much engagement in stakeholder relationships as an end in itself, neglecting the commercial objectives.

- Over-complicating customer segmentation – between three and five categories is about right.

- Over-promoting yourself to stakeholders with high influence, but little interest.

- Completely ignoring the low-influence, low-interest stakeholders; their impact may grow suddenly and unexpectedly – for example, through a new lobbying group.

Top takeaways

- Managing stakeholders, including external stakeholders, is a fundamental part of management.

- Managing stakeholders can be overdone, but if it is neglected, this can be disastrous.

- A customer-centred business is going to be the most successful, but it may require a cultural and organisational transformation.

- Customers should be a key input in any strategy development. In a commercial organisation, customers are the people who provide the revenue to keep the business going.

1 Based on Gulati, R., ‘Silo busting: how to execute on the promise of customer focus’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 85, no. 5, May 2007.

2 http://www.managementexchange.com/story/project-bushfire-focussing-might-entire-organization-consumer

3 Talk by Matthew Key, O2 CEO.

4 Melanie Healey interview, 30 Sept. 2011, AP interview.

5 Abram, J. and Hawkes, P., Seven Myths of Customer Management: How to be Customer Driven without being Customer Led, John Wiley, 2003.

6 Buttle, F., Customer Relationship Management: Concepts and Technologies, 2nd edn, Butterworth Heinemann, 2009, p. 261.

7 Ibid., p. 257.

8 Lysons, K. and Farrington, B., Purchasing and Supply Chain Management, Pearson, 2006, pp. 286–9.

9 Based on Effective Purchasing, CMI Checklist Series, no. 146, 2011.