chapter two

Models of internal

marketing: how internal

marketing works

Introduction

Despite the plethora of research, an examination of the literature shows that essentially there are two models of how IM works: one based on the work of Berry's concept of ‘employees as customers’ and the other based on Grönroos’ idea of ‘customer mindedness’ and interactive marketing1.

In the existing literature, most authors do not clearly distinguish between Berry's and Grönroos’ models of IM. The major reason for this is the fact that both Berry and Grönroos do not spell out the exact components of their models and how they are connected with each other. An examination of Berry's and Grönroos’ work (as well as their collaborators) on IM shows that both these authors are concerned with improving service quality. However, they differ in their methods for achieving it. A problem in examining the work of the two authors in this area is that they do not present systematic models of IM. Hence, what is presented below are the implicit models underlying the works of both Berry and Grönroos.

Berry's model of internal marketing

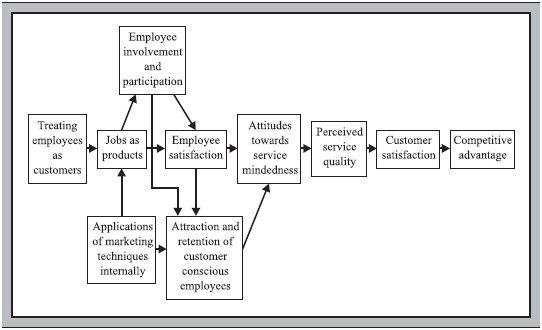

The distinguishing features of Leonard Berry's model are:

![]() The fundamental assertion that treating employees as customers will lead to changes in attitudes of employees; that is, employees becoming service minded, which leads to better service quality and competitive advantage in the marketplace.

The fundamental assertion that treating employees as customers will lead to changes in attitudes of employees; that is, employees becoming service minded, which leads to better service quality and competitive advantage in the marketplace.

![]() Treating employees as customers requires that jobs are treated as any other product of the company; that is, the needs and wants of the ‘customer’ are taken into account and an effort is made to make the product attractive to the ‘customers’.

Treating employees as customers requires that jobs are treated as any other product of the company; that is, the needs and wants of the ‘customer’ are taken into account and an effort is made to make the product attractive to the ‘customers’.

![]() Treating jobs as products requires a new approach from human resource management (HRM) and basically involves the application of marketing techniques internally both to attract and to retain customer-oriented employees.

Treating jobs as products requires a new approach from human resource management (HRM) and basically involves the application of marketing techniques internally both to attract and to retain customer-oriented employees.

The full model is presented in Figure 2.1.

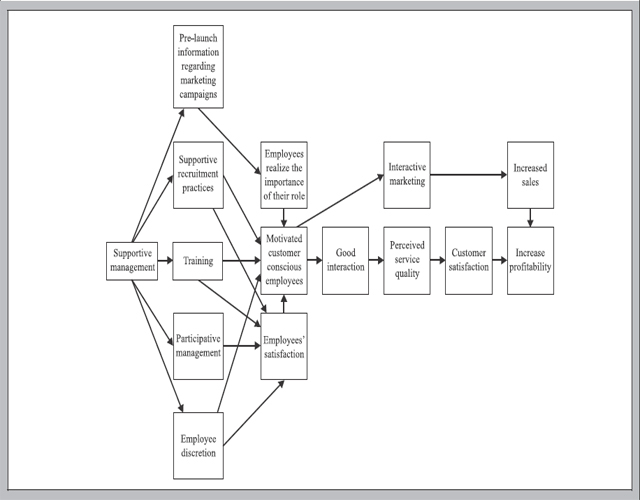

Grönroos’ model of internal marketing

Grönroos’ original model is based on the premise that employees need to be customer conscious and sales minded so that they can take advantage of interactive marketing opportunities, leading to better service quality and higher sales, and consequently higher profits.

![]() The precursors of customer-conscious employees are supportive recruitment practices, requisite training and participative management style, which gives employees discretion in the service delivery process so that they can take advantage of resulting interactions between contact employees and customers. By giving employeesdiscretion, that is by giving employees more control over their work, it is hoped that employee job satisfaction will increase and hence lead to more motivated and customer-conscious employees.

The precursors of customer-conscious employees are supportive recruitment practices, requisite training and participative management style, which gives employees discretion in the service delivery process so that they can take advantage of resulting interactions between contact employees and customers. By giving employeesdiscretion, that is by giving employees more control over their work, it is hoped that employee job satisfaction will increase and hence lead to more motivated and customer-conscious employees.

Figure 2.1 Berry's model of internal marketing.

![]() Additionally, employees need to be informed of any changes in marketing strategies and campaigns before they are launched on the external market. The idea behind this policy is that employees should thereby understand and realize the importance of their role in the service production and delivery process.

Additionally, employees need to be informed of any changes in marketing strategies and campaigns before they are launched on the external market. The idea behind this policy is that employees should thereby understand and realize the importance of their role in the service production and delivery process.

![]() All this requires a supportive senior management.

All this requires a supportive senior management.

The full Grönroos model is presented in Figure 2.2.

Whilst the objectives of the models are similar, it is clear that the mechanisms that they employ and their objectives are quite different. Moreover, the two models by themselves are incomplete in that the Berry model does not indicate the mechanisms that can be used to motivate employees other than a marketing approach. Similarly, the initial Grönroos model ignored a marketing-like approach to the motivation of employees. In order to provide a more comprehensive model of IM, both these approaches need to be combined.

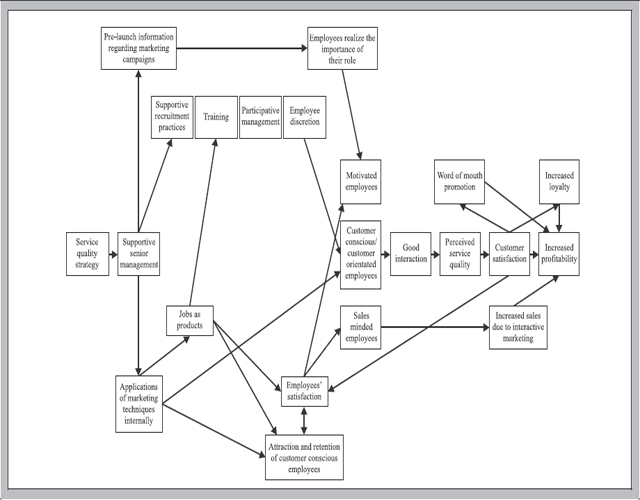

A composite model of internal marketing in services

The new model of IM derived from the combination of the Berry and Grönroos models is presented in Figure 2.3. A number of additional features in the model include the elaboration of the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty and increased profits. Profits are also increased by word-of-mouth promotion by satisfied customers.

The model also suggests that the antecedents of employee satisfaction are a function of adequate training, employee discretion and participative management. The job also needs to meet the needs of the employees. In addition, good communication between marketing and contact employee is also essential.

The proposed model has a number of advantages:

![]() The new model emphasizes the fact that the Grönroos and Berry models are not competing models but highlight different aspects of IM, and the new model uses these differences to build a more comprehensive conceptualization.

The new model emphasizes the fact that the Grönroos and Berry models are not competing models but highlight different aspects of IM, and the new model uses these differences to build a more comprehensive conceptualization.

![]() The model highlights a large number of implicit assumptions and relationships that need to be tested empirically.

The model highlights a large number of implicit assumptions and relationships that need to be tested empirically.

![]() The model shows the mechanisms involved in the implementation of internal marketing.

The model shows the mechanisms involved in the implementation of internal marketing.

![]() Whilst the model is somewhat more complex than the original models, it provides a more complete view of IM.

Whilst the model is somewhat more complex than the original models, it provides a more complete view of IM.

Figure 2.2 Grönroos’ model of internal marketing.

Figure 2.3 A meta-model of internal marketing.

Basis of the model

A closer examination of the model also shows that it links together a number of major issues in the marketing field, namely customer orientation, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and the linkages between employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. In effect, the proposed model provides an integrating framework for these issues. The major elements of the proposed model are discussed in more detail below.

Job satisfaction and its antecedents

A considerable amount of empirical research already exists on the antecedents of job satisfaction in the marketing area, particularly relating to salespersons in industrial settings2. This literature is relevant to services marketing because the boundary spanning nature of salespeople is similar to that of contact employees in services in that they have to deal directly with customers and to resolve the conflicting demands of customers on the one hand, and the organization on the other.

Much of this research is concentrated on the impact of role conflict and role ambiguity on job satisfaction. The results of these studies are fairly consistent in showing that role conflict, role ambiguity and role stress negatively affect job satisfaction3. In fact, after conducting an analysis of 59 studies, Brown and Peterson concluded that role conflict and role ambiguity were the key antecedents of job satisfaction4. Jackson and Schuler, in their analysis of 96 reported organizational studies on role conflict and role ambiguity, found that the most frequent and significantly correlated organizational antecedents of role conflict and role ambiguity were autonomy, feedback from others, feedback from task, task identity, leader initiating structure, leader consideration, participation formalization and level5.

Employees experience role ambiguity when they do not have the necessary information to do their job properly. Contact employees are more likely to experience role conflict because of the boundary spanning nature of their jobs as they attempt to reconcile the demands of the customers and the interests of the organization. The frequency, quality and accuracy of downward communication moderate role ambiguity. Role ambiguity can be reduced by training employees appropriately against the criteria used in the selection of employees6.

Linking service quality and customer satisfaction

The basic thrust of the service quality literature is that service quality leads to increased customer satisfaction. This is supported by a considerable amount of empirical evidence for the proposition that service quality is antecedent of customer satisfaction in services. The effects of loyalty include lower price sensitivity, reduced costs of attracting new customers as a result of word-of-mouth promotion, higher reputation of the firm and reduced impact of competitor's activities. For instance, Churchill and Suprenant found that perceived service quality directly affected satisfaction for durables. Oliver and Desarbo also perceived service quality had direct impact on satisfaction7.

Customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and profitability

In Berry's and Grönroos’ models, there is little discussion of how customer satisfaction leads to profitability. However, the link between customer satisfaction and profitability has been proposed by a number of researchers8. For Heskett et al., customer satisfaction operates via customer loyalty through to profitability. Other authors have simply proposed a direct link between satisfaction and profitability. Empirically, in the retail banking sector, Hallowell has shown that there were positive relationships between customer satisfaction and loyalty and between loyalty and profitability, but did not find any conclusive evidence for the satisfaction–loyalty–profitability hypothesis.

The costs of implementing service quality are not usually discussed in the IM literature. In fact, the link between customer satisfaction and profitability is likely to display diminishing returns. That is, increasing investments in customer satisfaction will lead to decreasing returns after a point, which suggests that there exists an optimal level of satisfaction that the firm should be aiming for.

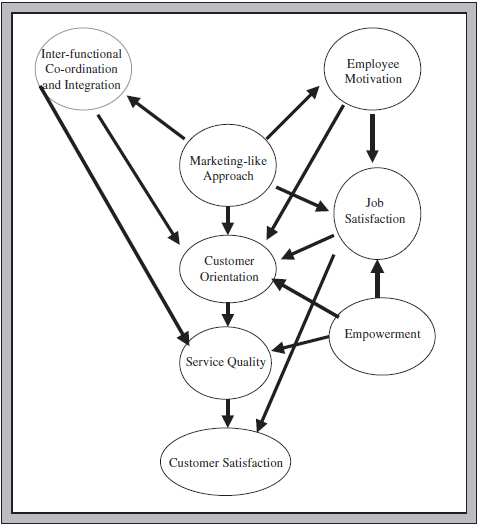

Developing a researchable internal marketing model

Whilst the model presented in Figure 2.3 shows how IM works, it is too complex. Figure 2.4 restates the relationships in the model in a more tractable form. The relationships indicated in Figure 2.4 are derived directly from the IM literature. For instance, the motivation of employees via marketing-like activities is explicitly stated from the early literature onwards. Grönroos and others also recommend the marketing-like approach to improve the inter-functional co-ordination and hence customer orientation. Inter-functional co-ordination and integration are central to more recent IM literature. Improving customer orientation of the organization has been a central concern of the IM concept from its inception. More recently, the central reason for interest in IM has been the potential contribution of IM to effective implementation of strategies via increased inter-functional co-ordination and employee motivation.

Figure 2.4 A framework for internal marketing of services.

At the centre of this framework is customer orientation, which is achieved through a marketing-like approach to the motivation of employees, and inter-functional co-ordination. The centrality of customer orientation reflects its importance in the marketing literature and its central role in achieving customer satisfaction and hence organizational goals. In fact, according to two sets of leading researchers in market orientation, inter-functional co-ordination is an essential facet of market orientation9.

The inclusion of the empowerment variable is essential for the operationalization of Grönroos’ interactive marketing concept. In order for interactive marketing to occur, front-line employees need to be empowered; that is, they require a degree of latitude of over the service task performance in order to be responsive to customer needs and be able to perform service recovery. The degree of empowerment given to service employees is contingent on the complexity/variability of customer needs and the degree of task complexity. Empowerment in our model impacts on job satisfaction, customer orientation and service quality.

The empirical evidence on the relationships in the model is fairly limited and somewhat mixed. For instance, Hoffman and Ingram found that there was a weak correlation between job satisfaction and customer orientation, and that role ambiguity, conflict and job satisfaction explained only 9 per cent of customer orientation10. Kelley's study of bank employees also found a weak correlation of customer orientation with job satisfaction and motivation11. However, when the effects of role clarity and motivation were held constant, job satisfaction was found not to be a significant predictor of customer orientation. Furthermore, although the study found that there was no significant difference in customer orientation among four groups of contact employees (managers, officers, customer service representatives and tellers), the tellers were significantly more dissatisfied with their jobs and significantly less motivated than the other groups of employees. What this suggests is that employees are quite capable of separating their feelings about their jobs (job satisfaction) from the actual performance of the job. Siguawet al.12 found that customer orientation was not related to job satisfaction; this is the inverse of the relationship proposed in IM models (i.e. job satisfaction leads to increased customer orientation). Herrington and Lomax13, in their study of financial advisers of the UK, found no relationship between job satisfaction and customer perceptions of service quality. However, they did find a weak relationship between job satisfaction and customer intention to repurchase.

In view of the above, instead of regarding employee satisfaction as a major precursor to performance, it can be regarded as one of a number of factors, such as employee motivation, customer orientation and sales mindedness, simultaneously determining productivity and the quality of the service. Hence, in our model the impact of job satisfaction on service quality occurs indirectly via customer orientation rather than directly between job satisfaction and service quality. This may partially explain the ambiguity in the empirical research noted above.

Summary and managerial implications

The model outlined in this chapter highlights the importance of employee attitudes in service quality via their impact on customer orientation, employee motivation and job satisfaction. Furthermore, effective service quality also requires high levels of inter-functional co-ordination and integration. Central to ensuring that employees have the requisite attitudes and high levels of inter-functional co-ordination is a marketing-like approach by management to these tasks. In addition, employees need to be supported by requisite levels of empowerment to deliver the required levels of service quality. Empowerment is also a key to service recovery, a key component in perceptions of service quality.

For managerial purposes, Figure 2.3 details how IM can be put into practice. Examination of Figure 2.3 shows the following:

![]() Supportive senior management is fundamental to the success of IM, as it indicates to all employees the importance of IM initiatives and thereby facilitates inter-functional co-ordination.

Supportive senior management is fundamental to the success of IM, as it indicates to all employees the importance of IM initiatives and thereby facilitates inter-functional co-ordination.

![]() The importance of communicating marketing strategies and objectives to employees so that they understand their role and importance in the implementation of the strategies and achievement of marketing and organizational objectives.

The importance of communicating marketing strategies and objectives to employees so that they understand their role and importance in the implementation of the strategies and achievement of marketing and organizational objectives.

![]() Employee satisfaction can be increased by treating ‘jobs as products’; that is, designing jobs with features that prospective employees value.

Employee satisfaction can be increased by treating ‘jobs as products’; that is, designing jobs with features that prospective employees value.

![]() Ensuring that employees are highly motivated, customer oriented and sales minded requires recruitment practices that attract and select employees with the requisite attitudes, providing employees the right type and level of training to perform their jobs, a participative management style and a degree of discretion (contingent on the service strategy of the organization) to front-line employees so that they can meet customer expectations and take advantage of interactive marketing opportunities.

Ensuring that employees are highly motivated, customer oriented and sales minded requires recruitment practices that attract and select employees with the requisite attitudes, providing employees the right type and level of training to perform their jobs, a participative management style and a degree of discretion (contingent on the service strategy of the organization) to front-line employees so that they can meet customer expectations and take advantage of interactive marketing opportunities.

![]() The importance of explicitly managing the interactions of employees and customers or ‘the moments of truth’ by training employees for customer orientation and 'sales mindedness’.

The importance of explicitly managing the interactions of employees and customers or ‘the moments of truth’ by training employees for customer orientation and 'sales mindedness’.

![]() The importance of using a marketing-like approach to the motivation of employees, and inter-functional co-ordination.

The importance of using a marketing-like approach to the motivation of employees, and inter-functional co-ordination.

Delivering high levels of service has its costs. For instance, service quality may be improved by providing employees with additional or better training. However, this has a consequence of increasing costs. Unless these costs are recovered by attracting extra customers, increase in repeat purchases or fewer service delivery mistakes, there will be a negative impact on profitability. Hence, this suggests that there is an optimal level of service quality that management should be aiming for, not necessarily the highest. The level of service quality that an organization offers is contingent on its positioning on service in the marketplace.

References

1. Berry, L. L. (1981). The employee as customer. Journal of Retail Banking, 3 (March), 25–8. Grönroos, C. (1985). Internal marketing – theory and practice. American Marketing Association's Services Conference Proceedings, pp. 41–7.

2. Churchill, G. A. Jr, Ford N. M. and Walker, O. C. Jr (1974). Measuring the job satisfaction of industrial salesmen. Journal of Marketing Research, 11 (August), 254–60. Churchill, G. A. Jr, Ford N. M. and Walker, O. C. Jr (1976). Organizational climate and job satisfaction in the salesforce. Journal of Marketing Research, 13 (November), 323–32. Rogers, J. D., Clow, K. E. and Kash, T. J. (1994). Increasing job satisfaction of service personnel. The Journal of Services Marketing, 8 (1), 14–26. Singh, J., Verbeke, W. and Rhoads, G. K. (1996). Do organizational practices matter in role stress processes? A study of direct and moderating effects for marketing-oriented boundary spanners. Journal of Marketing, 60 (3), 69–86.

3. Behrman, D. N. and Perreault, W. D. (1984). A role stress model of performance and satisfaction of industrial salespersons. Journal of Marketing, 48 (Fall), 9–12. Lysonski, S., Singer, A. and Wilemon, D. (1988). Coping with environmental uncertainty and boundary spanning in the product manager's role. The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 3 (Winter), 5–16. Siguaw, J. A., Brown, G. and Widing, R. E. II (1994). The influence of the market orientation of the firm on sales force behaviour and attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 31 (1), 106–16. Teas, R. K. (1983). Supervisory behaviour, role stress, and the job satisfaction of industrial sales people. Journal of Marketing Research, 20 (February), 84–91.

4. Brown, S. P. and Peterson, R. A. (1993). Antecedents and consequences of salesperson job satisfaction: meta-analysis and causal effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 30 (February), 63–77.

5. Jackson, S. E. and Schuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36 (1), 16–78.

6. Walker, O. C., Churchill, G. A. Jr and Ford, N. M. (1977). Motivation and performance in industrial selling: present knowledge and needed research. Journal of Marketing Research, 14 (May), 156–68. Walker, O. C., Churchill, G. A. Jr and Ford, N. M. (1975). Organizational determinants of the industrial salesman's role conflict and ambiguity. Journal of Marketing, 39 (January), 32–9. Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A. and Berry, L. L. (1990). Delivering Quality Service. New York: The Free Press.

7. Anderson, E. W. and Sullivan, M. (1993). The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms. Marketing Science, 12 (Spring), 125–43. Churchill, G. A. and Suprenant, C. F. (1982). An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 19 (November), 491–504. Cronin, J. J. Jr and Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: a re-examination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 52 (3), July, 55–68. Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: the Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 55 (January), 1–21. Oliver, R. L. and Desarbo, W. S. (1988). Response determinants in satisfaction judgements. Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (March), 495–507.

8. Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C. and Lehmann, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58 (3), 53–66. Gummesson, E. (1993). Quality Management in Service Organizations: An Interpretation of the Service Quality Phenomenon and a Synthesis of International Research. Karlstadt, Sweden: International Service Quality Association. Hallowell, R. (1996). The relationships of customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and profitability: an empirical study. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7 (4), 27–42. Heskett, J. L., Sasser, W. E. and Hart, C. W. L. (1990). Breakthrough Service. New York: Th Free Press. Reicheld, F. F. and Sasser, W. E. Jr (1990). Zero defections comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68 (September/October), 105–11. Rust, R. T., Zahorik, A. J. and Keiningham, T. L. (1995). Return on quality (ROQ): making service quality financially accountable. Journal of Marketing, 59 (2), 58–70. Schneider, B. and Bowen, D. E. (1995). Winning the Service Game. Boston, MA: HBS. Strobacka, K., Strandvik, T. and Grönroos, C. (1994). Managing customer relationships for profit: the dynamics of relationship quality. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5 (5), 21–38.

9. Kohli, A. K. and Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing, 54 (2), 35–58. Jaworski, B. J. and Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 57 (3), 53–70. Narver, J. C. and Slater, S. F. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of Marketing, 54 (5), 20–35.

10. Hoffman, D. K. and Ingram, T. N. (1991). Creating customer orientated employees: the case in home health care. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 11 (June), 24–32.

11. Kelley, S. W. (1990). Customer orientation of bank employees and culture. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 8 (6), 25–9.

12. Siguaw, J. A., Brown, G. and Widing, R. E. II (1994). The influence of the market orientation of the firm on sales force behavior and attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 31 (1), 106–16.

13. Herrington, G. and Lomax, W. (1999). Do satisfied employees make customers satisfied? An investigation into the relationship between service employee job satisfaction and customer perceived service quality. In Marketing and Competition in the Information Age, Proceedings of the 28th EMAC Conference (L. Hildebrandt, D. Annacker and Klapper, D., eds), 11–14 May, p. 110. Berlin: Humboldt University.