3

Aspects of development form

This chapter looks at the physical elements that together create a building or place:

- Layout

- Scale

- Density

- Materials

- Detail

These are aspects of development that are considered in planning applications, and which planning policies and guidance often seek to influence. Together they shape the characteristics of the place and influence how successful it will be. While Chapter 2 looked at what characteristics planning should be aiming to create, this chapter discusses how this can be achieved through our system of plans and permissions.

What the NPPF Says

‘Design policies should … concentrate on guiding overall scale, density, massing, height, landscape, layout, materials and access of new development in relation to neighbouring buildings and the local area more generally.’ (Paragraph 59)

Layout

Layout is the way in which buildings, routes and open spaces are placed in relation to each other. It provides the two-dimensional structure on which all other aspects of the form and uses of a development depend. As such, layout is one of the most important factors in determining the impact and success of development. Layout is often categorised as structure (large scale) or urban grain (small scale). An area’s pattern of blocks and plot subdivisions may be respectively small and frequent (called fine grain), or large and infrequent (coarse grain).

The layout of development affects how people and goods move around. At the scale of a town or city, the layout of urban development will influence such major issues as whether people travel to work by car or public transport (see Figure 3.1).

At the scale of a neighbourhood, layout will influence such things as whether children walk to school or are taken there by car. At the scale of a building, the internal and external layout of a development will determine where people enter and exit, and whether they use lifts or stairs inside.

Perimeter blocks

Many schemes today use layouts based on perimeter blocks. These are buildings or groups of buildings surrounded by public streets or spaces, where the building fronts face the public space (usually a street), creating a more or less continuous building frontage along it. The individual buildings may be semi-detached houses, terraced houses or blocks of flats, or anything else. This layout is often characteristic of relatively dense urban development. Perimeter blocks can be crucial to the configuration of urban space. They also offer the advantage that any back gardens and private areas are inaccessible to public spaces, making them less vulnerable to intruders.

The inside of the blocks may take the form of quadrangles, courts or gardens, among other forms. However, the main quality of this kind of layout is that the buildings create a clear frontage to the streets they face, while enclosing shared or private space behind. It is a layout that can be repeated across a large area, and added to in the future, and many examples are popular and enduring. However, perimeter blocks can seem regimented and soulless if they are not planned and designed with care.

Figure 3.1

The red line indicates the area from which people can walk to the town centre in around ten minutes to access the services it provides. The more intricate and connected the movement network, the bigger this area would be.

Figure 3.2 Common layout types include perimeter block, grid and cul-de-sac. This drawing shows perimeter blocks and a culde-sac within a connected grid of streets and open spaces.

Perimeter blocks may include buildings of varying heights on different sides, with lower ones on the south side to let sun into the centre of the block. It is important to consider the scale and design of individual building elevations in relation to the street as a whole, particularly with elevations that are opposite or adjacent each other. These relationships can be more important than those between elevations on opposite sides of the same block (and thus facing different streets), as these might not be experienced together by those using the area.

Grids

A grid is a network of streets that intersect approximately at right angles. Whether it is rectilinear, concentric or irregular, a grid is likely to be part of a well-connected network of streets. Many layouts include grids, as these suit perimeter block buildings. However, grids can seem alien to places that are older, more organic and of irregular form. Grids of any type form the basis of street-focused layouts, with front doors directly onto streets, which are generally an efficient way of using space and creating successful places.

Cul-de-sacs

A cul-de-sac is a street open at only one end, usually with a turning area at the other. Cul-de-sacs fail to contribute to a permeable network of connected streets, instead creating isolated, car-dependent enclaves. Large-scale planning based on cul-de-sacs creates urban sprawl. However, culde-sacs are often popular with the people who live in them, as they prevent through traffic and can create a form of semi-private open space.

Radburn layout

A Radburn layout is a type of housing design that segregates traffic and pedestrians. Cul-de-sacs for vehicles serve one side of a line of houses, and footpaths serve the other side. The layout, used widely in the 1950s and 1960s, was often unsuccessful, partly because it blurred the important relationship between the fronts of buildings, useful public routes and space, and private or shared open space. This can make such layouts inefficient, and the place difficult to navigate and feel less safe and cared for. In a Radburn development it can be difficult to know which is the public route and which is private space; where the entrances are to buildings; and who is looking over and after open spaces. In many cases Radburn estates have been modified to provide combined vehicle and pedestrian access from one side, and the cul-de-sacs have been linked to create connected routes. However, some Radburn layouts are still being built today.

At the street scale, one of the most important issues relating to layout is how car parking is accommodated. In the recent past it was thought that parking courts were the solution: sited behind the housing, courts allowed streets to be relatively narrow and not dominated by cars. However, experience shows that householders are extremely reluctant to park anywhere other than immediately in front of their homes, which has prompted the search for new solutions, such as on-street provision.

Consider

- Whether new development will fit in well with the surrounding layout, link up with its routes, and feel like a homogeneous part of the neighbourhood.

- Whether the layout represents an efficient use of space and allows for a positive relationship between buildings and spaces.

- Whether it will be clear what is private or public space, and whether front doors and windows to more public building uses will face public space.

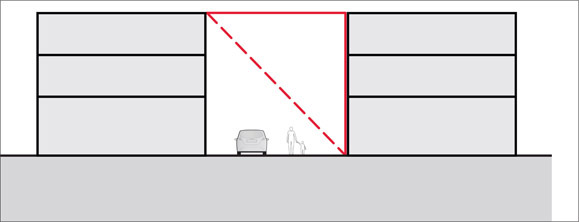

Figure 3.4 In many new streets in higher density areas the width of the open space is similar to or smaller than the height of the buildings. In a busy place this might feel unduly narrow.

Figure 3.3 In many high streets the space between the buildings is around twice as wide as the height of the buildings that front it. This tends to create a balanced sense of enclosure and spaciousness.

- How people will move around, and whether opportunities to provide the most direct and short routes for those walking and cycling have been taken, even if these routes are not open to motor vehicles.

- Whether the layout respects the topography of the area, the character of the neighbourhood and the orientation of the site to ensure that it does not feel separate.

- Whether the scale of blocks, streets and spaces feels appropriate to the surroundings, and for the uses to be accommodated. Excessively large blocks of homes can feel impersonal.

Scale

Scale is the size of a building or other development in relation to its surroundings, or the size of parts of a building or its details, particularly in relation to the size of a person. Scale can be expressed in relation to surrounding buildings, or in terms of a maximum length of frontage or facade, maximum dimensions of a street block, or a ratio of building height to street or space width (see Figures 3.3 and 3.4).

The scale of a development is often expressed in terms of height and massing. Height can be described by the following:

- Number of floors

- Height of building shoulder, parapet or ridge

- Overall height

- Any of the above in combination with the number of floors

- A ratio of building height to street or space width

- Height relative to particular landmarks or background buildings

Massing is the three-dimensional expression of the amount of development on a given piece of land. A building’s massing is sometimes referred to as its bulk.

Consideration should be given to the scale, massing and height of proposed development in relation to that of adjoining buildings; the general pattern of heights in the area; and views, vistas and landmarks. How a development will be seen from around the area must be carefully considered to avoid a negative impact on the surroundings.

It is important to consider how scale is perceived. Much will depend on the detailed design: how interesting the facade of the building is, how it relates to other nearby buildings, and what sort of spaces it creates. Breaking a large building up into several visual parts can help. This might be done by indenting sections along the front elevation, creating the appearance of a few separate buildings rather than one long one, or by setting higher sections back so they are not visible from the street. Scale can sometimes be camouflaged by making two storeys look like one in the elevation, perhaps with two windows set within a deep surround that covers two internal floors.

The impact of a building is likely to depend on where it is seen from. Some buildings are too dominant close up, but work better from a distance. Others might look good close up, but spoil a distant view.

Figure 3.5

The scale of the parts of a building, such as shop windows, can be as important as its overall height. Here the shop windows are excessively tall in relation to people and the proportions of the street, the pavement and other elements of the buildings.

Sometimes applicants attempt to justify a large building by calling it a landmark (or even an icon), or by saying that it will mark a gateway, or a corner or public space. It is important to make sure that these assertions are appropriate and justified (they often are not), that if justified a particular size of building is needed to achieve the objective (it often isn’t) and to ensure that the visual impact will relate clearly to the use and position of the building. A new place of worship might well be seen as a positive landmark where a massive office building would not.

Planning often focuses on the overall height of a proposed development, or on its depth. But the scale of its parts, particularly at ground and first-floor levels, is important too. For example, the developer of a retail development might feel that the operators will require tall shop windows and large signs, but this could make the area uncomfortable or uninviting for passers-by (see Figure 3.5).

Consider

- The different dimensions that make up scale, depth and width – not just height. For schemes such as individual houses, remember that the depth will have an effect on the roof shape, potentially leading to excessively steep pitches.

- How the scale of the proposal overall fits with the surrounding area; whether the gradient or other topographic features will help to mask or accentuate it; and whether it will, in time, become integrated into the neighbourhood.

- The impact of features described as landmarks, gateways and icons. Are they really needed? Will they be anything more positive that just a dominant structure in the townscape?

- The scale of parts of the building as well as its whole, and how these will work on the ground and first floors, as experienced close up.

- The scale of spaces as well as buildings, and the relationship between the two.

Density

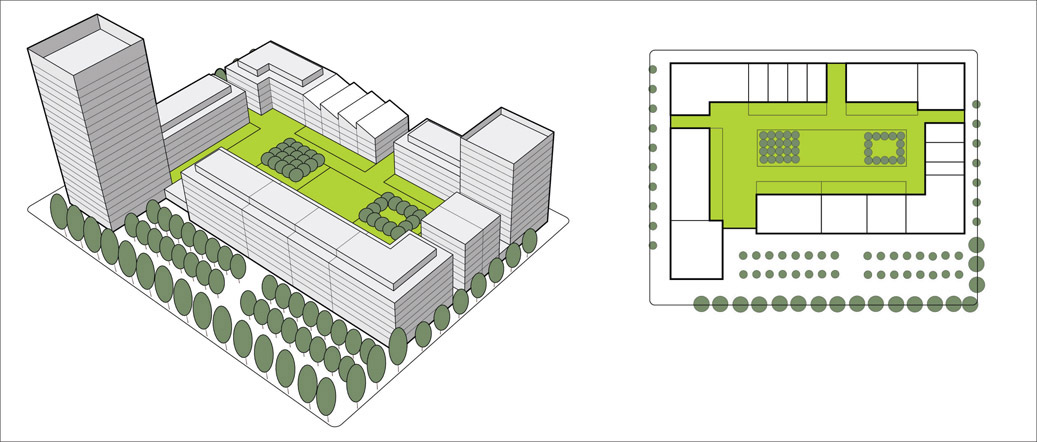

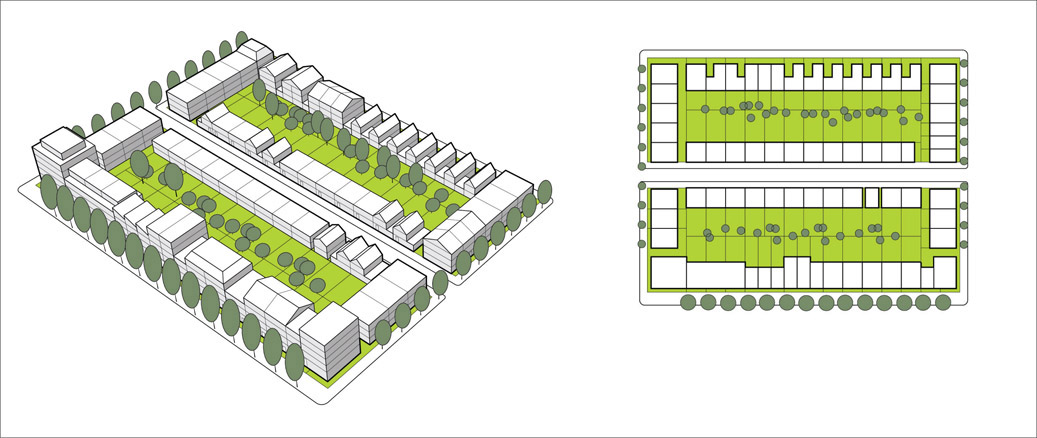

Density is the amount of development on a given piece of land. The concept is important to planning and design as a means of managing growth targets, the amount of activity and the demand for services; influencing the scale and massing; and making the best use of available land. Density influences the intensity of land use and, in combination with the mix of uses, can affect a place’s vitality and viability. A particular density does not necessarily determine the form of development: the same density can be provided through different building types. However, usually a particular building form and scale, combined with decisions on the amount of open space provided, will influence the density achieved. Figure 3.6 shows how three common development forms, and open space provision, can be accommodated on the same-sized site. They all achieve different densities, and each might be the most appropriate for a particular site depending on physical context, the housing market and so on.

The first example, Figure 3.6.1, shows a scheme that provides both communal (within the buildings) and public (next to the street) open space, so less of the site is covered by buildings. A taller element is included to provide the required built floor space. This layout, sometimes called a Vancouver block, is widely used in North America and, more frequently, in the UK. This example creates a density of approximately 232 dwellings per hectare.

The second example, Figure 3.6.2, shows a traditional perimeter block – a doughnut of buildings, in this case made up of different forms, which surround small private gardens and a central communal space. The buildings are sited tightly against the surrounding streets and no public space is provided. This example creates a density of approximately 161 dwellings per hectare.

The third example, Figure 3.6.3, shows a traditional terraced street. As the buildings tend to be less deep, and there are private gardens but no communal or public space is provided, an extra street can be fitted in. This example creates a density of approximately 86 dwellings per hectare.

Each example has its benefits and disbenefits, for example the third will have lower maintenance costs than the first. They all represent good use of the site.

Density ranges prescribed in policy can be helpful in establishing broad development potential, but they only represent a starting point. Local context, design and the potential for placemaking are essential considerations in determining the appropriate form and density for a particular development. Care should be taken when using density figures, as they can be expressed in different ways.

Residential density

Residential density is the number of dwelling units, rooms or bedspaces in a given area. This is usually measured in hectares. Density can also be expressed as a figure for floor space per hectare, including residential and non-residential space. As shown in Figure 3.7, different ways of expressing density take account of different parts of the buildings. For example, if habitable room or bedspace figures are used, these will not include roof space, kitchens and bathrooms. These do not indicate the actual amount of building on a site, but they are useful indications of the number of people who could be accommodated.

Density is a measure of the amount of development in a particular area. Where the boundary of that area is drawn will affect the density figure. Planning normally uses the red or dotted yellow area shown in Figure 3.8. But the development relies on facilities in the purple area, and with bigger sites these kinds of spaces will be included in the density calculation. Planners can also usefully think about the carrying capacity of the wider area, shown in blue.

Net residential density

Net residential density is the number of people, rooms or housing units on a development site. The net residential site area excludes space around the site that will serve its residents, such as paths, streets, rivers, canals, railway corridors and other existing open spaces. It includes the proposed homes, ancillary uses, car and cycle parking areas, and proposed internal access roads. It also usually includes proposed on-site open spaces (including publicly accessible spaces), gardens and play areas.

Gross housing density

Gross housing density is the number of people, rooms or housing units, including uses not necessarily directly relevant to the figure (such as roads and other transport infrastructure) in an area. The area can be defined as the functional catchment for the homes and may not be just the development site.

Figures 3.6.1, 3.6.2 and 3.6.3

Different densities achieved using different building forms on the same site.

Figure 3.7

Different ways of expressing density take account of different parts of a building. These diagrams illustrate what is included within each measurement method.

Figure 3.8 The areas used to measure gross, net and neighbourhood densities.

What the figures mean

There is no right or wrong way to express density: the various methods can be useful for different planning functions. For example, the measure of habitable rooms per hectare gives a reasonable idea of potential residential occupation. A development with mainly small dwellings will tend to have a greater built volume than a development with the same number of habitable rooms per hectare with more large dwellings, as there will be more kitchens, bathrooms and halls (among other elements) not counted in the figures. A figure of the number of dwellings per hectare can be useful when considering how a scheme contributes to meeting housing targets, but it will not reflect actual building volumes or occupancy potential, as the figure will be affected by the size and type of dwellings. Small flats will provide more dwellings per hectare than family houses with the same building volume, but they may not be able to accommodate as many people.

For schemes with a vertical mix of uses, such as homes above offices and shops, the non-residential space will need to be taken into account within density calculations. One method of working this out involves discounting a proportion of the site area used for non-residential uses (up to 30%) and then applying residential densities to the remaining site area. This effectively raises the calculated residential density. If the non-residential component accounts for more than 30% of the total, it can be best to apply plot ratios.

Plot ratio (sometimes referred to as floor area ratio) is the ratio of the total floor area of a building (including all the storeys in the building) to the area of land on which it is built. So 100 square metres of floor space on a 100-square-metre site will have a plot ratio of 1:1 (1). The same plot ratio can result in many different building forms: in this case, a single-storey structure covering the whole site, or a two-storey building on half the site, and so on. Plot ratios can be combined with guidance on building heights and plot coverage to establish the development parameters for different sites.

Development parameters can be a useful addition to just using density figures on plans and scheme assessments. They may specify that a certain amount of the site needs to be kept as open space, that buildings abutting streets must be set back a specific amount after a particular height (to avoid creating a canyon effect) or that pitched roofs, if used, should not exceed a particular pitch (so that they look and work like pitched roofs). For higher-density development, daylighting rights to neighbouring buildings often create a parameter envelope (an area of airspace that the new building is not allowed to go into). Such parameters will affect the density that can be achieved, so the figure will be derived from the design process, rather than being a major input to it. This can be a successful planning approach, but the parameters, and their impact on what can be built, need careful testing.

Every housing type has a range of densities within which it tends to work well. Above that range there may be problems with lift provision, privacy, daylight and amenity space.

Consider

- Why you are interested in the density figure. It may be a useful indicator of whether housing targets are being met, but it will not be a good indicator of the likely form, quality or appropriateness of any scheme.

- How you want the building amount to be measured (homes, habitable rooms, bedspaces, floor space). What will the chosen measure tell you?

- Whether you are looking at net or gross densities, and whether these relate to housing and other land uses, and/or the size of the area being fed into the calculation.

Figures 3.9.1 and 3.9.2 Materials, detailing and maintenance help to determine the success of a place.

Figure 3.10 These intricate balconies help to give the scheme a distinct identity.

- What works in your area, and the type of scheme and densities you feel can be accommodated acceptably.

- That car parking uses a great deal of space, with a significant impact on density figures.

Materials

Materials are the matter from which a development – buildings, structures and spaces – is made. The choice and treatment of materials will affect a wide range of issues, including the following:

- How many non-renewable resources are consumed in manufacture, transport and construction

- How easy buildings and structures will be to reuse and recycle

- How much toxic material they will emit

- How much glare they will reflect

- How well they will insulate the building

- How long they will last

- How they will weather

- How easy they will be to repair or replace

- How well the buildings will fit in with their natural and man-made surroundings

The texture, colour and pattern of materials can all influence a development’s impact on people who see it and use it, at the scale of individual buildings and the wider townscape.

Figure 3.9 shows two residential blocks and the space they enclose. They are of similar scale but appear very different, mainly because of the materials and detailing, and how well they have been maintained. The brick building is much newer, but it should require less maintenance than the older block. These examples are part of a housing estate regeneration scheme, with the older blocks being replaced by the newer ones.

It can be difficult to visualise material specifications, as there is a huge range of products on the market, and descriptions, names and textures often change. It can be useful to ask for samples and built examples of the materials being proposed, and sample panels can be useful. In the case of bricks, the sample should include features such as corners or window details to show how the material will work in the actual building.

Check the lifespan and maintenance requirements of materials. For areas on public view, and which might be hard to clean or maintain, make sure robust materials are used that will weather well. If the material demands a specific maintenance or cleaning regime, include details in any permission.

Whether a material will be successful in a particular situation will depend on how it is designed, detailed, specified, constructed and maintained. Check how materials relate to the way in which gutters and drainpipes are dealt with in the scheme. Even the best rendering will deteriorate if rainwater from the roof runs down it.

Consider

- Whether the materials are appropriate for the way in which they are to be used, whether they will last, and if they will be practical to clean and maintain.

- Whether the materials relate well to the style and design ethos of the scheme. For example, are traditional materials being used for a sleek, minimalist modern style, or new materials for a vernacular approach?

Figure 3.11 Bricks can be used in creative ways to make a scheme look more attractive.

- Whether the materials complement those used in the surrounding area.

- Whether the materials will stand up well to the local climate and air-quality conditions.

Detail

How well a development works, and its impact on the people who use and experience it, will be influenced significantly by the detail: by the skill applied to its detailed design, by how its parts fit together, and by the care with which it is built. The human experience of buildings and of architecture is partly a response to the work of human hand and mind. Buildings that reflect thought and care contribute to making a place seem human and friendly. Figure 3.10 shows balconies that have been detailed with a design found in pottery excavated from the site. The detail, unique to this scheme, helps to give it a particular identity.

Matters of detail with which planning may be concerned include:

- Building elements such as openings and bays

- Entrances and colonnades

- Balconies and roofscape

- Craftsmanship

- Building techniques

- Architectural styles

- Facade treatment

- Depth of window recesses

- Drainpipe routes

- The lighting of a building or structure

- Planting and boundaries treatment

Detail can add texture and character to a scheme. In recent years brick has been used in new ways, allowing it to be relatively cheaply incorporated to add interest and individuality. Figure 3.11 shows brickwork used to create a channel for the drainpipe, making each individual terraced home look somewhat separate from its neighbours.

Consider

- The detailing might be what people will notice first about the new building or place, so it should not be left until the end of the list of planning considerations.

- The care given to detailing a scheme illustrates the developer’s approach, and the long-term interest that they have in the quality of the area.

- Detailing and materials go hand in hand. Some materials offer better opportunities for careful detailing than others.

- Detailing can add visual depth, interest and individual character to both buildings and spaces. It can also mask less appealing functional requirements, such as bin stores and drains.

- Good detailing can add something special to a scheme, eliciting interest, acceptance and even pride.