CHAPTER 4

Micro Entrepreneurs

Small loans can transform lives, especially the lives of women and children. The poor can become empowered instead of disenfranchised. Homes can be built, jobs can be created, businesses can be launched, and individuals can feel a sense of worth again.

Natalie Portman1

The average micro entrepreneur has a low income that is generated from a self‐employed activity in either craft or agriculture. Overcoming poverty raises fundamental needs such as education, health and consumption, which may all be satisfied with an extended MFI loan portfolio.

Most micro entrepreneurs live in regions such as Asia Pacific and Latin America. In many cases they operate a small business or work in agriculture.

4.1 DEFINITION

The most important protagonists in microfinance are the micro entrepreneurs, ultimately the recipients of an investor's capital. The effects of these funds on micro entrepreneurs are the very core of microfinance. What needs do these micro entrepreneurs have, and how can microfinance help to meet them? In which geographical regions do micro entrepreneurs live and in what industries are they active?

Micro entrepreneurs are the clients in microfinance. Without microfinance they would have no access to capital. The rural population in developing countries in particular is largely excluded from the financial system. The typical micro entrepreneur has a low income that is generated from a self‐employed activity in either craft or agriculture. In order to sell their handiwork or agricultural product, they often operate small businesses or market stalls.2

Over the last few years, the microfinance sector has been professionalized. The breadth and quality of the products and services that are being offered by MFIs amply document this fact. Earlier models were designed to continuously increase the supply of microloans. The volume of loans may still be central; however, it has become increasingly evident that efficient financial services for poorer segments of the population must be tailored to the market and its clients to meet their needs.3 A better understanding of the needs of the target group will inevitably lead to a more customized range of products. Micro entrepreneurs do not just want to take out loans, they want to save a part of their earnings or they may need special financial support for their children's education or their family's health.

4.2 NEEDS AND REQUIREMENTS

To best meet the needs of micro entrepreneurs, clients are segmented according to their economic circumstances. Demands within these different poverty levels vary and they therefore require different products and services. The following describes the different poverty levels and discusses the needs of micro entrepreneurs on their way out of poverty. With a second, third or further loan for education, health matters and consumption, successful micro entrepreneurs can send their children to school, make provisions against illness and smooth out their consumption.

Poverty Levels

Poverty has many faces and far‐reaching consequences. Low‐income parts of the population suffer from lack of food, lack of access to clean water and a lack of accommodation. Economically, they may be struck by unemployment, underemployment or exploitation of labor. Distressingly, people who cannot satisfy their most basic needs feel socially underprivileged and humiliated – a condition in which they incapacitate themselves both socially and politically. For this reason, many people afflicted by poverty frequently suffer from physical, mental and emotional disorders, have limited skills and a low level of education, which often goes hand in hand with feelings of self‐consciousness and low self‐esteem. The term “poor” is rather nondescript and includes all the aforementioned segments of the population. Yet there are significant differences within these segments of the population that need to be taken into consideration. There are the poor whose elementary needs are not at all or only partly satisfied – be it as a result of a food deficit or insufficient access to water – and whose income is barely enough to cover the loans they have taken. These people differ substantially from the poor who own minimal property – for instance a plot of land or real estate – and who either have a regular occupation or run a micro business. In many cases, the second group has successfully managed to raise themselves above the first group. Poverty as such does therefore not exclusively refer to a low income but rather denotes the fact that elemental needs cannot be met.4

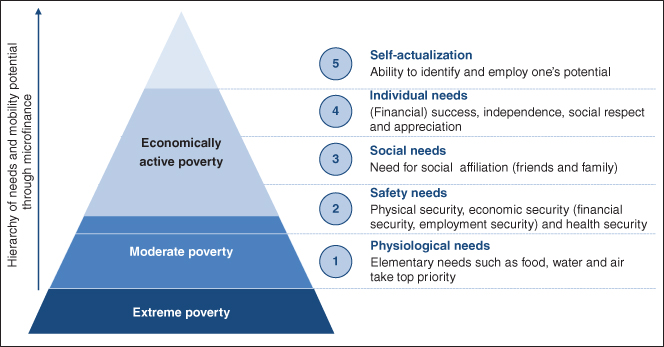

We distinguish between three poverty levels – extreme or abject poverty, moderate poverty and economically active poverty (see Figure 4.1).5

FIGURE 4.1 Poverty Levels

The World Bank attributes the term “extreme poverty” to segments of the population that live on less than $1.9 a day, which is below the breadline.6 Extreme poverty describes those segments of the population that:

- Are either unemployed or underemployed and whose remuneration is so low that their spending capacity is insufficient to cover their daily caloric requirement

- Live in resource‐poor regions

- Are either too young or too old to work

- Are too frail to work

- Have no prospect of employment because of their ethnicity, gender or political views

- Are fleeing from catastrophes that are caused by man or nature or

- Have neither property nor family members or relatives to support them.

The term “moderate poverty” refers to segments of the population that have an income that just suffices to cover elementary needs.7 Basic requirements such as food, water, clothing and accommodation can therefore be fulfilled. However, they cannot provide for healthcare at this stage.

“Economically active poverty” describes those segments of the population that have a stable and secure income which allows for enough food, keeps sickness at bay, secures an adequate form of healthcare and allows for asset accumulation.8

The distinction of the different poverty levels is not conclusive. Households may change levels at any given time, e.g. when a qualified person has no employment for a while, or when the living standards of a particular household improve. Gender‐related differences may be an issue too, as women often do not have the opportunity to acquire certain skills or pursue a particular profession. This may lead to discrepancies in poverty levels between men and women living under the same roof. Individuals with an occupation often remain on a lower poverty level because their income barely covers their basic requirements.9

And yet, from the point of microfinance, the distinction between extreme, moderate and economically active poverty is a useful tool. This differentiation allows for a factual assessment of the needs of the different segments of the population and paves the way for a sustainable availability of products and services. In commercial microfinance this distinction in terms of client structure facilitates the categorization of clients into those eligible or perhaps less eligible for a loan. The category of the economically active poor thereby refers to people on a low to slightly higher income. In this group there is a high demand for financial services that go beyond a microloan.

Requirements of Micro Entrepreneurs

Microfinance is a tool in the fight against poverty and improves the living standards of the low‐income population in developing countries.10 The escape from poverty is synonymous with a transition of the aforementioned poverty levels. The requirements of the different poverty levels are displayed in Maslow's hierarchy of needs. The hierarchy refers to an individual's survival, identity and self‐actualization.11

Figure 4.2 merges Maslow's hierarchy of needs with the different poverty levels. The hierarchy, or pyramid in this case, comprises five levels. The first level refers to the physiological needs, elementary requirements such as food, water and air that need to be satisfied first. The second level represents an individual's need for security. Despite the fact that physical security takes priority, this category also displays economic security and stability in the wider sense, e.g. financial security, stable employment and protection from illnesses. The third level reveals an individual's need for social affiliation (friends and family). Theoretically, this need is only generated when the first two categories have been largely satisfied. Such a rigid view, however, fails to do the different poverty levels justice. Social and societal exclusion often go hand in hand with extreme poverty, independently of the fulfillment of an individual's elementary needs. The second but last level on the pyramid displays an individual's need for success, independence and social appreciation. Finally, self‐actualization is at the very top of the pyramid. It refers to an individual's ability to identify and consequently employ his or her own potential.

FIGURE 4.2 Poverty Levels and Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Data Source: Maslow (1943); World Bank (2014)

Merging the different levels of need and poverty reveals that the range of products in microfinance is crucial. The extremely poor are unable to meet their elemental health requirements. These segments of the population will benefit from their loans for the best possible start of their business activities that will cover most elemental needs such as food and water. In most cases, it is their first microloan. Although the moderately poor manage to satisfy their elemental needs, they do not have any economic security such as perhaps a stable employment, nor can they rely on adequate healthcare. Many on this level are on their second or third microloan. The economically active poor have already progressed to the upper levels of the hierarchy of needs and therefore are more likely to demand a wider range of services. These individuals are highly likely to have taken out microloans before, and successfully used them for business activities. Microfinance encourages individuals to rise within the hierarchy of needs by providing an adequate range of loans and further financial services. A tailored and client‐oriented approach fosters this upward mobility and therefore constitutes an integral part of microfinance.12

Broader Range of Loans

A change in living standards inevitably leads to a shift in the needs of microfinance clients. The social and particularly the individual requirements go far beyond the traditional conceptions of microloans. As loans for education, healthcare and consumption do not primarily serve to generate income, they are limited to micro entrepreneurs with a stable income. Loans for healthcare lend themselves to any level of poverty. Education loans are only issued above a certain level of income, and consumer loans demand a stable income and business activity. Healthcare loans are particularly important for the extreme poor, because in the event of illness they are usually unable to work and consequently lose their remunerations. If they fail to repay a loan that has been taken for their business activities, any subsequent loan application will be rejected and severely hamper their rise in the hierarchy. An accommodation loan in times of illness, however, may restore their health and in turn secure repayment.

Quite often, micro entrepreneurs will invest their generated income in their children's education. The children of MFI clients are thus more likely to partake in an educational program than those of other low‐income families. There also is a much lower risk that they will leave school prematurely.13 Long‐term and sustainable investments in education ensure that following generations can continue this upward mobility in the social hierarchy and that their acquired skills will allow them to generate a secure income and achieve economic stability. A rise in living standards will trigger the need for specific educational services in addition to the traditional types of loans – namely literacy programs and business development services. Training programs that provide basic economic and entrepreneurial knowledge promote local business networks to the benefit of micro businesses in their bid to position their business and develop it sustainably.

Bad health and insufficient access to the health system are both the cause and effect of poverty. For one thing, inadequate healthcare triggers a disproportionately high prevalence of illnesses in poorer regions. At the same time, the costs in connection with illness are soaring, and they involve the risk of further impoverishment. A bad state of health has a detrimental effect on a micro entrepreneur's productivity and severely compromises business development. Healthcare loans are an affordable and comfortable means of raising capital that offers protection against risks associated with illness.

As healthcare loans are not used to generate income, they bear certain risks for MFIs. Yet, inadequate healthcare in many cases leads to insolvency and subsequent exclusion from microfinance programs. Some micro entrepreneurs are known to have resigned due to illness, which has a negative effect on the repayment quota of traditional microloans.14 In the world, an estimated 100 million people are forced below the poverty line as a consequence of significant and unexpected healthcare expenditures. The complex microfinance insurance products are not yet sophisticated enough. Healthcare loans thus present a viable option in a micro entrepreneur's attempt to avoid sinking into poverty and to reduce the business risk of MFIs.15

Consumer loans widen the range of products of MFIs. Ultimately, consumer loans aim to smooth out a client's cash flows, particularly because quite apart from their daily expenses, many households face substantial expenditures such as weddings, funerals and other exceptional situations. Requirements such as these are normally met by savings or intakes from business activities. Consumer loans, however, also satisfy individual needs and therefore go beyond the satisfaction of purely elementary requirements. There may be a demand for these loans, yet they are not offered by default, as many MFIs assess a client's debt capacity based on the cash flow generated by their microbusiness activity. Where no consumer loans are offered, business loans often take their place and are utilized for consumption purposes. The rising demand for consumer loans especially with economically active segments of the population, however, also demonstrates that MFIs are indeed steadily developing their range of products and services.

4.3 MICRO ENTREPRENEURS

The number of MFI clients has risen rapidly over the last few years. Compared to ten years ago, clients who request the financial and non‐financial services of microfinance have multiplied by around five. The success of this concept not only manifests itself in the rising number of clients, but in the proportion of people who have escaped poverty. When the MDGs were formulated in 2000, they stipulated that there were still two billion people living on less than $1.9 a day. Almost 20 years later, this figure has been reduced by half.16 Financial integration empowers people to cast off the shackles of poverty and to operate and finance their business activities sustainably.

Regions

Over the last few years, microfinance has outgrown its idea as a local tool in the fight against poverty and has transformed into a global phenomenon with the aim of financially including all low‐income segments of the population. Figure 4.3 shows the countries with the highest proportion of those living in poverty, with 30 per cent of the poorest of the poor living in India, 10 per cent in Nigeria and 8 per cent in China. Strikingly enough, particularly Asian and African countries seem to be afflicted most by poverty.

FIGURE 4.3 Countries with the Highest Proportion of Poor People Worldwide

Data Source: World Bank (2016), database 2012

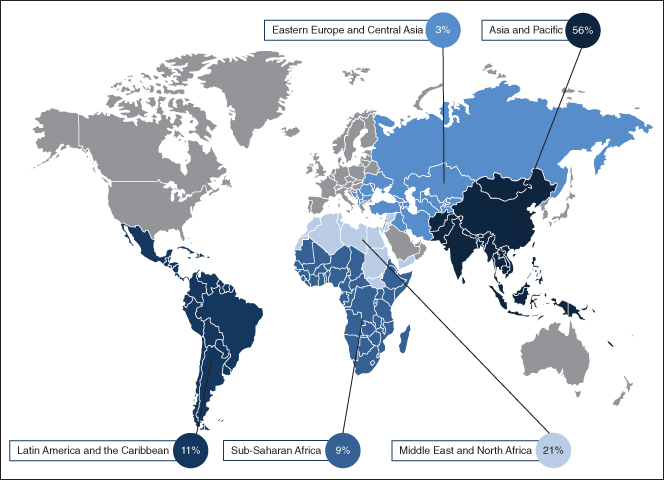

A look at the geographic distribution of the number of active borrowers (see Figure 4.4) reveals that more than half are from the Asia Pacific region (median), 11 per cent are in Latin America and the Caribbean, 30 per cent in Sub‐Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa. A total of 3 per cent of the active borrowers worldwide live in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.17 Comparing these results with those of Figure 4.3, it becomes evident that in the future, microfinance programs have to be promoted much more effectively to reach the poorest of the poor, not just in Asia but particularly in Sub‐Saharan Africa.

FIGURE 4.4 Percentage of Active Borrowers, According to Region

Data Source: MIX (2016), database 2014

Figure 4.5 demonstrates that at $194 and $292 respectively, the poorest regions such as South Asia and Eastern Asia and Pacific have the lowest average loan (median). In more progressed microfinance markets such as Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the average loan is considerably higher at $1243 or $1871 respectively. The average microloan for all regions is at $1174.

FIGURE 4.5 Average Loan Balance Per Borrower According to Region

Data Source: MIX (2016), database 2014

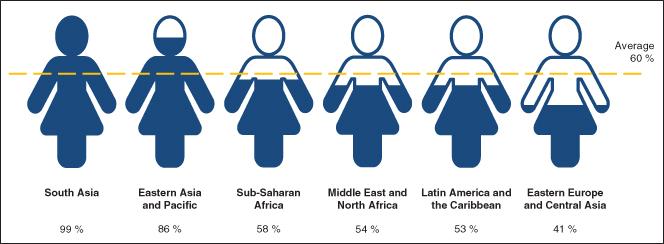

Gender

In the microfinance industry more loans are granted to women than men on average (see Figure 4.6). In South Asia, an average of 99 per cent of loans were handed out to women. Distinctly, in regions such as Eastern Asia and Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and in North Africa as well as Sub‐Saharan Africa, more than half of all loans are issued to women. Eastern Europe and Central Asia are the only exceptions, with the share of women dropping below the 50 per cent mark. Why women and not men constitute the larger target group of MFIs will be explained in Chapter 6.

FIGURE 4.6 Percentage of Female Borrowers, According to Regions

Data Source: MIX (2016), database 2014

Industries

The business activities of microfinance clients feature in different economic sectors and vary in terms of required capital resources and services. To an MFI, the distinction between rural and urban clients is central. The decision to serve the one or the other client group is decisive in their product development. If the sector is subject to a negative economic development, both microfinance clients and MFIs face a considerable business risk. Typical micro enterprises in urban regions are often part of the small trade and small businesses. They offer a specific product for the local trade or offer their services in one form or other. Micro entrepreneurs in rural regions mostly engage in agricultural activities, as well as in cattle farming, fishing or craft.

Figure 4.7 displays the share of the different sectors of the volume of credit of several MFIs into which a BlueOrchard managed fund has been invested: 32 per cent of this volume of credit flows to micro entrepreneurs that engage in trade, 28 per cent goes to agricultural enterprises, 21 per cent to service providers, 6 per cent flows to social housing and 5 per cent to industry. The majority of all loans are issued to the trade business because demand for business capital and the exchange of goods is particularly high. The agriculture and services sectors also demand high capital investments (cattle stock, localities and so on) that are mostly covered by external funding.

FIGURE 4.7 BlueOrchard: Volume of Loan According to Sector

Data Source: BlueOrchard Research

Balance Sheet of a Micro Enterprise

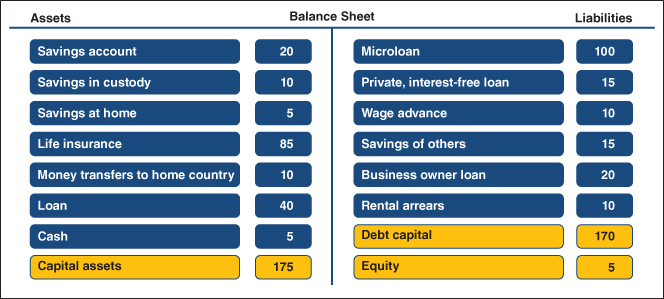

The balance sheet of a micro entrepreneur in Bangladesh (see Figure 4.8) clearly shows that people in developing countries lend money to one another and take custody of each other's savings. Savings deposits and pensions (e.g. life insurances) are of great importance.

FIGURE 4.8 Balance Sheet of a Micro Enterprise in Bangladesh (in $)

Data Source: Collins, Morduch, Rutherford and Ruthven (2009), p. 9

4.4 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

There are essentially three poverty levels: extreme, moderate and economically active poverty. The extremely poor fail to even satisfy their most elementary requirements. The financial means of the moderately poor only just cover basic needs and rudimentary healthcare. Economically active segments of the poor population have enough food and better healthcare. Aligned and adequate microfinance services allow and promote upward mobility within the different poverty levels. Micro entrepreneurs can satisfy their respective needs with the help of their business activities to elevate themselves from poverty, step by step.

A target‐oriented satisfaction of needs is a key aspect in microfinance. It comprises a steadily growing range of financial services that include – among traditional microloans – loans for education, healthcare and consumption.

Most micro entrepreneurs have low income that is generated from a self‐employed activity in either craft or agriculture. Geographical provenance and economic activity are further decisive factors.

Most micro entrepreneurs come from the regions Asia Pacific (two thirds of all borrowers) or Latin America and the Caribbean (a fifth of all borrowers). The average credit volume received is $502 and active borrowers are mostly females. The largest volume of loans is issued to micro entrepreneurs that engage in small businesses and trade, as well as agriculture. For micro entrepreneurs, it is vital to keep their savings and lend to each other. Other securities, such as life insurances, are of the utmost importance.