CHAPTER 5

Microfinance Institutions

The key to ending extreme poverty is to enable the poorest of the poor to get their foot on the ladder of development. . .the poorest of the poor are stuck beneath it. They lack the minimum amount of capital necessary to get a foothold, and therefore need a boost up to the first rung.

Jeffrey Sachs1

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are of great importance in microfinance because they provide services to micro entrepreneurs. MFIs are a blend of a range of service providers that use their market position to supply small‐scale financial services to people who are usually excluded from the benefits of a sound financial system.

MFIs employ savings deposits and loans as well as donations and subsidies for funding purposes. They primarily provide financial services in the form of microloans and savings deposits. Often, however, they also offer services such as micro insurance and micro pensions.

Credit granting, deposit taking and a wide range of non‐financial services foster the financial integration of the poorest of the poor and promote the fight against poverty in a sustainable manner. By means of provident loan granting, optimal asset allocation can be achieved. This boosts productivity and at the same time allows individuals to benefit socially and economically, ultimately much to the benefit of the entire national economy.

5.1 DEFINITION AND GOALS

The term “microfinance institution” is rather general as it refers to a large number of financial institutions. So far, no standardized definition has prevailed. This perhaps explains why many institutions interpret both the mission and services of MFIs in different ways. In the past, MFIs were often understood as private organizations that were offering financial services but were not commercial private banks. When it comes to MFIs, the United Nations distinguish between microfinance and inclusive finance. This takes into consideration that the industry is changing – in a shift in paradigm – by moving away from classic microfinance towards more efficient and more comprehensive financial sectors.

While microfinance can be defined as the supply of different financial services to poorer segments of the population, it is becoming increasingly difficult to unite the growing number of providers in this market segment under one term. Variety is the issue: there are NGOs, private commercial banks, state banks, postal banks, non‐bank financial institutions (NBFIs), credit cooperatives, savings cooperatives, as well as several associations and organizations.2 Most of these institutions have attracted a large clientele and offer a range of diversified financial services. Technically, their rather general market orientation, however, qualifies them more as MFI in the broader sense. The term “MFI”, therefore, more strictly speaking denotes formal and semi‐formal financial service providers whose main purpose is the provision of financial services in the lower market segment.

The choice of a potential target market depends on the goals of these MFIs and the expected demand in connection with them. There are numerous households and businesses that are either only partly served or not at all. They range from the extremely and moderately poor to the economically active segments of the population that create employment locally. This range ultimately represents the demand side for microfinance financial services. In many cases, however, the supply side lacks the necessary products to meet this need. MFIs are indispensable as they bridge this gap in supplies and include parts of the population and businesses that have been excluded from the financial system. Quite apart from that, MFIs must also be classified as development organizations whose ultimate aim is to reduce poverty, increase productivity and income of the poor, and strengthen the role of women.

MFIs create work places for the underprivileged segments of the population and foster economic growth. Any market entry requires careful examination and assessment of the different local conditions against the backdrop of the long‐term goals of MFIs and microfinance in general. Generally, financial inclusion and economic and social sustainability are an integral part of it. The financial situation of an MFI therefore depends on its target market and influences decisions concerning their goals and how they can be attained. For this reason, MFIs have to assess carefully in which markets there is a demand for financial services and which of the client groups are in line with their long‐term goals if they want to implement their business models sustainably. An MFI that aims to supply financial and non‐financial services to the most destitute segments of the population will therefore be substantially different from one that exclusively focuses on financial services for the economically active poor. Targeted goals on the other hand can also be reached by purposely putting a focus on selected economic sectors or activities.3

5.2 TYPES OF MFIs

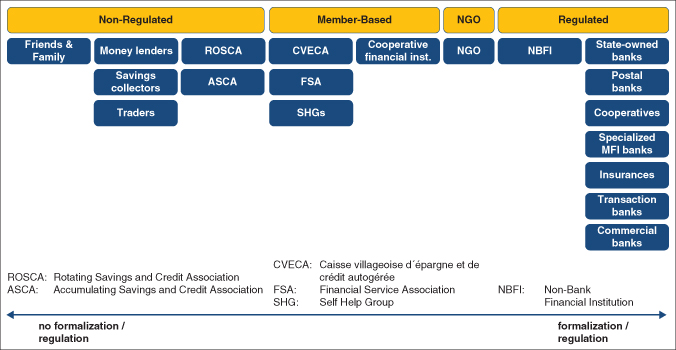

Microfinance institutions consist of private, public or charitable organizations and usually have social and financial goals, which is why they are often described as organizations with a double bottom line. Figure 5.1 displays the distinction of microfinance service providers into regulated, non‐regulated and member‐based institutions as well as NGOs. The following in short describes the most important institutions with respect to their international funding.4 No further notice will be given to non‐regulated and member‐based MFIs, as they do not qualify for international funding. NGOs can be split into two groups: those that predominantly supply microloans and those that additionally offer healthcare and education services alongside their more elementary financial services. NGOs are subject to civilian and commercial law and are largely funded by donations and subsidies. The main focus of their business activities is the financial integration of the poor and the improvement of their living standards. Unlike banks, NGOs are neither regulated nor under continuous supervision. As a result, they are unable to take and manage deposits of microfinance clients.

FIGURE 5.1 Different Forms of MFI Organizations

Data Source: Ledgerwood (2013)

Non‐Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs)

This group of institutions consists of, for instance, former NGOs that have undergone a transformation process. Their range of services is usually limited to loans and services (mostly group loans) without collateral. Some institutions – in certain cases and under certain supervision – are capable of taking deposits.

State Banks and Postal Banks

State banks were founded by governments in order to promote particular sectors, such as agriculture, and to reach poorer segments of the population that had been left unbanked by commercial banks. These banks served as a vehicle in transfer payments. Despite the fact that some amply fulfill their mandate, many had to close as a result of mismanagement. Postal banks are able to use the infrastructure of the largest distribution network in the world. In many countries they offer savings and transaction services and are market leaders, particularly in rural areas.

Financial and Credit Cooperatives

This group of finance providers comprises communal savings and credit cooperatives as well as credit unions. They are defined as charitable organizations and are usually owned by their respective members. The proceeds that are generated beyond the operative costs are paid out as dividends, capital stock, increased interests on savings deposits, reduced credit rates, insurance rates or other services. Within the framework of these organizations, micro entrepreneurs are to be understood as stake holders who can profit from both their access to financial services and the resulting proceeds.

Specialized MFI Banks

MFI banks are rigorously regulated also via legal and institutional parameters. These MFIs are either independent or work as a subsidiary of a larger bank. The business model of these banks respects a social component and understands microfinance as a profitable core activity. Unlike commercial banks, the offer of MFIs is designed to target microfinance clients and serves a broad segment from the lowest to the highest income bracket.

Insurance Companies

Insurance service providers increasingly offer their products in developing countries. Profit‐oriented and charitable organizations, government organizations as well as insurance companies are all among these providers. Sales figures in the lower income brackets are relatively low as yet. Insurance products have not been established in most places and are regarded as additional services more than anything else. In addition to this, insurance companies do not offer their services to the clients directly, but often act as re‐insurers for MFIs that in turn offer insurance services such as buildings or life insurance, or credit risk insurance.

Transaction Banks

Enterprises specializing in transactions dominate the simple and secure transfer of financial means between countries for the low to middle income brackets. Further providers of transaction services are commercial business banks and postal banks, but also MFIs and NGOs. Their services comprise, for example, the transfer of money or the backing of a credit limit of bank cards of foreign relatives. These services are profitable thanks to the fees that are charged. This is clearly an incentive to recruit more clients, who in turn benefit from access to credit and savings deposit services.

Commercial Banks

The supply of services for households with a low to middle income can present a profitable business model to commercial banks. The variety of services stretches from savings accounts and transaction services to loans. A presence in this market segment either depends on a government mandate, competitive pressure or expectations of potential future growth.

5.3 MFI FUNDING

According to estimates, there are nearly 4000 MFIs worldwide.5 Although many of these institutions offer similar services, they differ considerably in type, funding and regulation. The funding of MFIs deserves further investigation.

Financial Sources

Originally founded as charitable enterprises, the activities of MFIs were mainly funded by donations and subsidies of governments, development organizations, foundations and private people. Over time, some of these organizations have developed into formal financial service providers or regulated banks, increasingly so in recent years. Formal financial institutions are better equipped to achieve financial independence and sustainability, as they are able to refinance on the capital market and can take deposits.6 Moreover, in many countries only regulated MFIs are authorized to offer certain services.

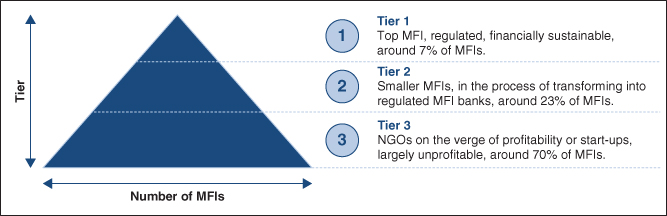

The financing strategy of an MFI depends on its profitability and development. By and large, MFIs can be put into three categories: Tier 1, tier 2 and tier 3 institutions, as shown in Figure 5.2. Tier 1 and tier 2 MFIs are distinguished by their economic stability and are increasingly state‐regulated. Tier 1 institutions are predominantly state‐regulated banks that are rated by rating agencies. They are funded by savings deposits, loans and equity. Tier 2 institutions consist of smaller and younger MFIs. They are predominantly organized as NGOs aspiring to be regulated banks or they are already undergoing the transformation process. For this reason, tier 2 MFIs can also fund themselves via loans and equity. Depending on how far this transformation process has progressed, they may also take deposits to fund their activities. Most MFIs are classified as tier 3 institutions. They constitute roughly 70 per cent of the microfinance sector, but are yet to be financially independent or sustainable. Tier 3 institutions are on the one hand MFIs on the verge of profitability but still lacking the necessary funds. On the other hand, this group also comprises NGOs and startup MFIs that are mostly unprofitable and have a purely social agenda.7

FIGURE 5.2 Types of MFIs

Data Source: Microrate (2013a)

Many financial institutions and organizations – such as microfinance vehicles, local and international banks, development and supra‐national organizations, as well as international capital markets and sponsors – facilitate the funding of microfinance institutions. Tier 1 MFIs on the whole are given more attention by commercial banks and institutional and private investors, as these MFIs not only reveal a great degree of economic stability, but usually also have rather experienced managements that put their social mission into action. Hence, from an investor's point of view, these MFIs efficiently and effectively channel means to micro entrepreneurs. Tier 1 MFIs in particular thus have better access to both local and international capital markets and investment funds. For this reason they are able to take out loans in addition to their equity capital in order to reach more entrepreneurs. Many of those MFIs are holders of a banking license, and are authorized to take deposits. Some tier 2 MFIs also receive funding from international investors, albeit much less funding than tier 1 institutions. The vast majority of all MFIs in tiers 2 and 3 lack a comparable professional and commercial business structure and therefore have limited access to the capital market. Their microloans are funded via loans from development organizations or sponsors.8

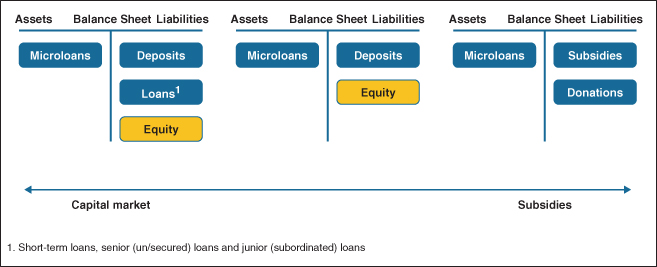

Figure 5.3 shows that the assets on the balance sheet of an MFI represent the loans issued to micro entrepreneurs, whereas the liabilities depend on their form of funding, legal structure, regulatory framework and the supply of services.9 Equity, international or local capital markets, savings deposits, as well as subsidies from governments, supra‐national organizations and private persons are particularly adequate sources of funding. The left‐hand side of Figure 5.3 represents the assets of an MFI that are open to competition and not subsidized. It can therefore fund itself via savings deposits, loans from the international and national capital market or via its equity. The balance sheet on the right represents an MFI that can only employ subsidies and donations to fund its business activities.

FIGURE 5.3 Forms of Financing of MFIs

Data Source: Becker (2010) and Dieckmann (2007)

However, not all institutions follow this funding pattern in their development. There is thus no conclusive overall capital structure that would fit every stage of their development. More importantly, their funding structure depends on internal factors such as the expansion of the loan portfolio and the taking of deposits. It also depends on external factors such as the regulatory framework, the availability of sponsors or commercial credit institutions and the development of the local financial system. Finally, the costs and maturities of the various sources of funding are also decisive in the choice of optimal structure.

International Equity

The volume of the portfolio of outstanding microloans has surged in the last ten years. This development can largely be explained by a facilitated access to commercial funding via international loans and local savings deposits. This trend is reflected in the foreign investments made in the microfinance sector. They almost doubled between 2007 and 2012 to around 17 billion dollars.10

An average MFI mainly funds itself via local sources (see Figure 5.4). Deposits from microfinance clients contribute around 45 per cent of the balance sheet of MFIs. In addition to this, microloans are financed via local debt capital at 20 per cent and local equity at 10 per cent. This means that foreign investments only constitute around 25 per cent of the overall funding of an average MFI.11 Considering the costs of financing incurred, this structure hardly surprises. Equity, if not in the form of donations, is the most costly source of financing and is therefore rarely an option. It is followed by debt capital that usually prevails over the former as it incurs lower costs. Savings deposits are clearly favored as the most reasonable form of re‐funding.

FIGURE 5.4 Funding Structure of MFIs

Data Source: Becker (2010)

In an ideal world, and with respect to any future market development, MFIs should aim to increase their funding via local means. Adamantly so, because microfinance answers to underdeveloped markets in developing countries, and its main objective in the development of such markets is the mobilization of local means and the efficient utilization of these funds by way of local financial institutions.

Financial Orientation

Subsidies, donations and handouts create no incentives for sustainable economic activity, and they do not foster independence or freedom in micro entrepreneurs. Profit‐oriented MFIs, however, ensure that financial means are implemented in a target‐oriented, effective manner in order to promote business activities in their region. A lack of traditional banks that specifically align their commercial activity with poorer clients does not imply that low‐income segments of the population are bad clients. On the contrary. The most notable accomplishment of microfinance lies in the fact that the poor can indeed be good and reliable clients for a bank. Informal lenders such as money lenders, neighbors and local traders may have client‐specific information that traditional banks lack, but they are financially restricted. Microfinance thus is a problem‐solving approach that strives to best link the means of a bank with the information and cost advantages of a local money lender. The advantage of microfinance therefore lies in its ability to attract external funds. Historically, microfinance is not the first concept to do this, albeit certainly the most successful to this day. It essentially owes its success to the systematic avoidance of mistakes and pitfalls of the recent past.

In the 1970s, it was generally accepted that there were considerable subsidies necessary to provide financial services to poorer segments of the population. Often, state banks took on this task and issued the majority of loans to agricultural enterprises. Yet, many of those banks were driven by political agendas and calculated interest rates that were below the current market interest rates. In addition to that, loan repayments were not monitored systematically and very often not claimed with ultimate consequence. The loan granting risks and the questionable incentives when it came to repayment frequency and payment morale spawned expensive and inefficient institutions that failed to reach particularly the destitute segments of the population.12 Critics of the concept of subsidized banks argue that the poor are generally better off without these subsidies. They refer to the fact that subsidized banks force reliable informal money lenders out of the market, who in many places provide the poor with access to capital. On the other hand, the market interest rates of any given time are seen as a rationing mechanism. Only those with a project worthy of funding or a business idea with potential will be prepared to pay for a loan.

These subsidies pushed the interest rate for microloans well below the market interest rates. As a result, loans were no longer issued to the most committed and reliable borrowers, but in many cases, loans were granted on the basis of political agendas or social considerations. This severely undermined the basic concept of microfinance and was not by any measure economically sustainable. The steady flows of money from subsidies meant that banks had no incentives to offer savings services and poor households were left with unattractive and inefficient possibilities to invest their financial means. As banks were state‐managed, they were under immeasurable political pressure to regularly cancel loan debts, which again led to dire mismanagement. Financial means that were destined for the poorer segments of the population flowed into the pockets of influential individuals. In other words, there were no incentives whatsoever for the foundation of efficient and sustainable institutions. Consequently, with a few exceptions, state‐run loan programs suffered sizeable credit default rates, of 40 to 95 per cent in Africa, the Middle East, South America, South Asia and South East Asia. In such a system, the term “effective loans” hardly applies; they were rather government‐funded subsidies.13

In the 1980s and 1990s, the microfinance sector was subjected to more substantial changes that thrust the profitability issues of these microfinance institutions into the limelight. It was decided that in the future, MFIs should be financially sustainable. The decision to aim for a profit‐oriented type of microfinance can be put down to three arguments. First of all, the management of small credit volumes is more costly for banks. Yet, for want of a better option, poor households are prepared to pay higher interest rates. Annual interest rates of local money lenders regularly exceed the 100 per cent mark; anything less is therefore considered an acceptable option. Generally speaking, access to financial means is more important than the actual price. Secondly, subsidies do not only constitute the main problem in state‐run banks, but they may have a detrimental effect on NGOs too, by weakening the incentive for cost‐efficiency and innovation. Thirdly, is it assumed that volumes of existing and future subsidies will not suffice to sustainably promote growth in microfinance. Aligning its profitability and commercialization is therefore prerequisite to a speedy dissemination of the concept.

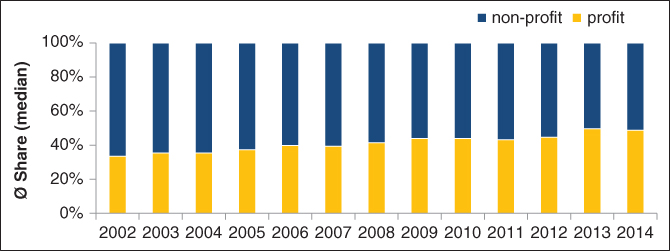

Figure 5.5 reveals the segmentation of the market into profit‐oriented and charitable MFIs. The development of a profit‐oriented microfinance sector is reflected in the relatively large proportion of profit‐oriented MFIs. In 2013, 380 out of the 766 MFIs that were registered on the MIX Market (Microfinance Information Exchange) data platform were profit‐oriented institutions. On top of this, these institutions collectively controlled more than 70 per cent of the total managed financial assets.14

FIGURE 5.5 Profit‐Oriented and Charitable MFIs

Data Source: MIX (2016)

Despite the fact that the choice of a profit‐oriented legal form should put more emphasis on profitability, this does not necessarily reflect reality. The mere decision to operate as a profit‐oriented institution is not the decisive factor. The form of enterprise does not imperatively determine sustainable economic activity. In many cases, charitable organizations are also profitable, albeit they might not pay out their proceeds but instead reinvest them for the benefit of their clients.15

Microfinance, with its social mission, is sometimes criticized because of the fact that some MFIs are profit‐oriented. Those in favor predict a stronger social impact in the future because high demands in terms of product efficiency and growing competition will stir up the traditionally rather less profit‐oriented market. Clients will benefit from more affordable and efficient services. Critics, however, are adamant that profit orientation is utterly incompatible with their goal to alleviate poverty, or that it will severely compromise it at least. They argue that profit orientation will eventually lead to a departure from microfinance's original goal of financially integrating the poor. It will at the same time lead to a slump in services as well as higher interest rates meant to maximize profit. The commercialization of microfinance has been placed in a bad light in recent years, its main reproach being uncontrollable growth and high interest rates. The data evaluated by the MIX Markets information platform, however, shows a different picture altogether when it comes to profit orientation of the microfinance sector. Those institutions that accumulate high proceeds, and that have aroused the general public's discontent, are statistical outliers and stand for a mere 10 per cent of all microfinance clients worldwide. The vast majority of clients use services from institutions where interest rates and return on equity (RoE) lie below 30 and 15 per cent respectively.

Historically, the returns on assets (RoAs) of profit‐oriented institutions even lie below those of charitable MFIs. In addition to this, both profit‐oriented and charitable MFIs have seen lower proceeds in recent years and are therefore hardly distinguishable in this respect. On the cost side too, there are not many differences. Profit orientation therefore does not mean profitable, and charitable does not inevitably lead to lower costs.16 Figure 5.6 shows the RoA of profit‐ and non‐profit‐oriented microfinance institutions.

FIGURE 5.6 Profitability of Profit‐Oriented and Charitable MFIs

Data Source: MIX (2016)

There seems to be a middle way when it comes to financing institutions. It is grounded in the belief that both profit‐oriented and charitable MFIs are capable of fighting poverty long‐term and generate sustainable business activities. They do not necessarily have to be in conflict with each other.

5.4 SERVICES

The transition of the microloan into comprehensive microfinance is predominantly a question of the range of services. In the past, emphasis was merely given to the supply of loans. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that the poor want to make use of a wider range of financial services such as savings deposit services or insurance products. Beyond that, there is a particularly high demand for non‐financial services. The challenge for MFIs hence is to meet this demand with a suitable supply. They therefore need to supersede issues relating to market entry, most of all when it comes to informing the general public about their individual products.

Product information leads to a better understanding of the rights and obligations that come with the territory, which again leads to a higher demand. Nearly all MFIs supply loan services, while some institutions also offer additional financial and non‐financial services. The range of services moreover depends on the goals of an MFI, the demand in its sales market and institutional structure. The most important aspect, however, is simply the supply of products that microfinance clients truly need and for which they are prepared to pay.

Financial Services

Beyond the microloan, MFIs also supply savings deposits, insurance and transaction services.

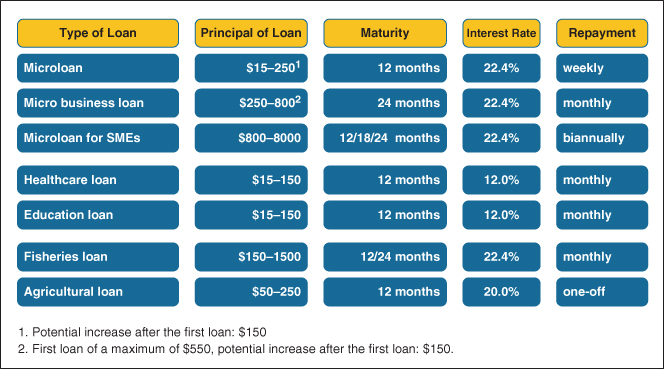

Loans are borrowed financial means with specific repayment conditions. It is sensible for microfinance clients to get a loan in situations where there is a lack of capital to fund a business and the proceeds of the borrowed capital exceed the interest rates of the loan. This prevents them from stalling their business activities until sufficient liquid funds for auto‐financing have been found.17 In many cases, MFIs also supply loans for healthcare, education and real estate as well as for other exceptional situations, as shown in Figure 5.7. MFIs aim to issue their loans in a sustainable, client‐oriented manner. Transactional processes have to be as efficient and affordable as possible. The interest rate has to be economically viable and clients must have an incentive to repay their loans. Loans may be issued to individuals or groups. Individual loans are often issued to individuals with a minimal guarantee or collateral to secure the loan. Group loans are generally handed to individuals with a group affiliation or groups that organize the further allocation of those loans. The group members agree to joint guarantee for the redemption of the loans. Many MFIs do not require collateral since only successful repayment will secure access to further loans. More importantly, the fact that the different group members vouch for each other is a major incentive for timely repayment.18

FIGURE 5.7 Example of Types of Loans of an MFI in Pakistan

Data Source: BlueOrchard Research

By taking deposits in recent years, an array of informal MFIs and financial institutions have demonstrated that there is demand for these services in low‐income groups. As the majority of poor segments of the population have no access to savings accounts with formal institutions, there is often no possibility for safe custody of their savings. Liquid assets are thus usually either “hidden” or entrusted to so‐called money keepers, whose fees, however, factually equate to a negative interest rate on their assets. Although even formal MFIs are now offering their savings deposit services, there is a supply gap that is largely due to the regulatory framework. Non‐regulated MFIs are not authorized to take deposits. MFIs that do collect them are therefore larger and most likely urban institutions. There are two types of product voluntary saving and mandatory saving. Voluntary saving happens at the client's own discretion. She or he has unrestricted access to their assets and receives an interest return. Mandatory saving means that the client is obliged to pay in order to be granted a particular loan. This may be a fixed amount or a percentage of the loan. This business model allows a client to benefit from institutionalized saving and an accumulation of wealth at the same time. Accumulated savings must, however, not be retired until maturity, and therefore act as a form of collateral. MFIs, on the other hand, profit from a stable source of funding to refinance loans and other services.

Insurance is a relatively recent and attractive addition to the range of products in microfinance. For poorer segments of the population in developing countries, the occurrence of daily hazards is significantly higher than in industrialized countries. Precarious living conditions increase the prevalence of illnesses and malnutrition. The quality of water and standards of hygiene are often poor. Inadequate safety precautions and the risk of environmental shocks greatly favor accidents of the poor. Micro insurance policies offer protection to a certain degree from these potential hazards. The supply of insurance products among other things includes life insurance, real estate insurance, health insurance and credit risk insurance, as well as some form of micro pensions.19 Some MFIs, such as Grameen Bank, have introduced mandatory insurance and insist that a certain percentage of their credit volume should flow into an insurance fund. In the event of death, the insurance policy will both pay for the loan and the costs of the funeral. MFIs often serve as distribution channels for insurance services.

In combination with savings services or for a fee, transaction enterprises and certain MFIs also supply transaction services. As Chapter 5.2 has illustrated, these services are essentially the transmission of money, the backing of credit limits on bank cards of foreign relatives and money transfers. As a payment is usually issued before a check is cleared, MFIs carry the risk that a number of checks cannot be redeemed due to fraud or insufficient funds. For this reason, few MFIs currently supply these services. A continually rising demand, on the other hand, will certainly bring more service providers to this business segment and promote better conditions to allow for an economically viable supply of these services.20

Non‐Financial Services

MFIs also supply non‐financial services. These range from social intermediation – with the aim of accumulating social capital and fundamental skills – to business development services (see Figure 5.8).

FIGURE 5.8 Non‐Financial Services of MFIs

Data Source: Parker and Pearce (2002)

Social intermediation helps poorer segments of the population to reach a better understanding of various issues, for instance, healthcare services concerning vaccinations, drinking water, or pre‐ and postnatal care in women, or education services such as literacy programs. Business development services are meant for established but also potential business entrepreneurs. They include a range of training programs, the building of business networks and a general supply of market information.

5.5 REGULATION

The regulation of MFIs comprises many aspects and critical requirements MFIs have to fulfill in terms of capital resources, liquidity and their loan portfolio.

Why Should MFIs Be Regulated?

The degree of regulation and supervision of MFIs is one of the most pressing issues in microfinance. While a number of formal MFIs in certain countries are already regulated, most semi‐formal and informal MFIs are not compulsorily subject to regulation. Deposit taking is, however. For this reason, many MFIs or NGOs fund their business models with deposits without authorization by simply renaming their services or by grace of the authorities, albeit at a considerable risk, as in the future even tighter rules and regulations may be implemented to counteract such cases, much to the disadvantage of all the protagonists in microfinance.21 Financial supervision aims to audit and monitor MFIs with respect to compliance. Regulation seeks to avoid a financial crisis in the microfinance sector, maintains payment transactions, protects clients and their savings deposits, and promotes competition and efficiency. Ultimately, however, regulation has to be organized in a way that avoids a distortion of the market.

When Should MFIs Be Regulated?

Despite their extensive growth, MFIs still only reach a small part of their potential host of clients globally. The supply of financial services for the microfinance market will in the long run exceed the capacity of traditional sources of financing (donations and development organizations). For this reason, MFIs will in the future be constrained to increasingly resorting to commercial sources and savings deposits for the funding of their microloans. However, the funding of MFIs and loan portfolios via commercial funds and savings deposits calls for rigid regulation and supervision mechanisms; not least because of the organizational structure of MFIs that differs considerably from that of traditional banks.22 The question, of course, is when MFIs should be regulated. Fundamentally, they should be regulated if they take deposits from clients, as microfinance clients are unable to correctly gauge an MFI's financial situation. They have to rely on an authority for this assessment. In addition to this, MFIs should also be regulated in the absence of minimum standards or in cases where they are disrespected, as often is the case when microfinance programs are launched prematurely and exclusively focus on loan granting. MFIs should also be regulated when they outgrow a critical size, and potential insolvency would have severe implications beyond the particular MFI and its clients.

What Are the Central Aspects of Regulation?

To do justice to the variety of MFI services, regulators distinguish between two types of MFIs: the non‐deposit‐taking MFIs, which only issue loans, and the deposit‐taking MFIs, which both issue loans and take deposits.

MFIs that take deposits from the local population pose a higher risk from a regulatory point of view than non‐deposit‐taking MFIs, as savings deposits can be withdrawn at relatively short notice.

In the event of a bank run, MFIs with a high share of deposits would be likely to run into trouble financially due to the fact that in most cases they invest the money entrusted to them in loans that are issued to micro entrepreneurs on a long‐term basis. Apart from these financial implications, there is a political dimension that must not be underestimated. A situation where clients are unable to withdraw their savings may easily lead to open rioting and social upheaval, and trigger a chain reaction that might have an adverse effect on other financial institutions. For this reason, deposit‐taking institutions are usually subject to regulation that regularly monitors and assesses the financial situation of MFIs and takes the necessary measures wherever required.23

The regulatory framework for deposit‐taking MFIs aims to protect depositors and the financial system alike with a number of instruments (see Figure 5.9). Most notably they regulate capital adequacy, minimum capital and liquidity.

FIGURE 5.9 Regulation and Supervision Framework

Regulation in terms of capital adequacy dictates the rules for the relationship between an institution's equity and (risk‐based) assets. This ratio is called the capital adequacy ratio (CAR). A high CAR means less risk for savers and the financial system. At the same time, a high CAR limits the ways of funding, or external funding respectively, and lowers productivity. This may reduce the supply and therefore limit access to financial services. This contradicts the purpose of an MFI. Various characteristics of microfinance, on the other hand, require comparatively higher CARs than traditional banks, which is associated with several topics of the microfinance portfolio: high operating costs, aspects of diversity, management skills and a limited availability of monitoring instruments.

Although MFIs have lower default rates than commercial banks, these may in many cases deteriorate rapidly as microloans are often not secured and the access to further loans is a micro entrepreneur's main concern. If a micro entrepreneur therefore is alerted to the default of others, default in general rises with MFIs. Moreover, a micro entrepreneur may feel betrayed if he or she serves their loan and others do not. In the event of a rise in default payments, MFIs are at more risk than commercial banks, as most of these banks have a diversified portfolio that only devotes a fraction to microloans. High operating costs are another issue. A rise in defaults results in less capital for MFIs that might be used to cover current overheads.

In many cases, MFIs operate in one region, which is why they carry a higher risk than banks, which are geographically more diverse. MFIs also require higher capital buffers, because of their relatively short track record and their lack of experience of both management and employees. Also, many regulatory authorities in developing countries have neither the necessary experience nor the instruments to assess and supervise risks in microfinance.24 In addition to this, MFIs often have limited means of funding in cases of emergency.25

Minimum capital requirements refer to the amount of equity that an institution must provide. Low capital requirements are synonymous with low market entry barriers and therefore more providers as a rule. On the good side, this promotes competition. However, a regulator only manages to supervise effectively a limited number of institutions, which in turn would speak for a higher entry barrier. The level of the minimum capital thus substantially depends on the size and structure of the market in question, and the rules and regulations vary from country to country.

Liquidity requirements refer to the provision of a minimal volume of liquid assets. Lower requirements allow for higher operative flexibility, but pose a higher risk at the same time. As loans that are issued by MFIs are usually short‐term, MFIs may interrupt their loan granting in cases of emergency in order to improve their liquidity. This may have dire consequences for their clients and should at all costs be avoided. For this reason, the liquidity requirements for MFIs are in many cases rather stringent.

Apart from prudential regulation, there is also non‐prudential regulation, which extends to deposit‐taking MFIs as well as non‐deposit‐taking MFIs. Non‐prudential regulation is also referred to as conduct of business and is mainly dedicated to client protection.

Client protection requires adequate and transparent information and may, for instance, mean that simple language is used to describe products, or that products are explained orally as many clients cannot read and write. To safeguard a fair conduct in client care, abusive loan practices have to be punished. Clients therefore must have a contact point where they can report cases of abuse free of charge. This is especially important because most microfinance clients cannot afford a lawsuit, be it for time or financial reasons.

Credit Bureaus

Alongside administrative regulation there has been a trend towards self‐regulation in recent years. Increasing competition on the financial markets has exacerbated issues of insolvency and marred repayment incentives as well as causing the ensuing financial difficulties for MFIs. The lack of a common information system worsens the problem, because the growing number of MFIs increases the information asymmetry among the individual loan providers. The introduction of credit information systems (credit bureaus) can make amendments and increase the efficiency of the credit market and boost the number of loans issued to the poor. If individual MFIs on a market begin to share data about their clients, they inevitably encourage other MFIs to follow suit. It is only logical that the exchange of information within the framework of a credit information system will lead to a better risk assessment of potential clients and therefore encourage other creditworthy borrowers to join their ranks; loan default rates will drop and the quality of loan portfolios will rise (see Figure 5.10). Ultimately, borrowers will also benefit from this increase in efficiency. The introduction of credit bureaus thus increases a financial system's efficiency and improves the position of each and every participant in the microfinance sector.

FIGURE 5.10 Credit Bureaus

If there is no exchange of information among MFIs, a borrower will find it more difficult to be granted a loan, especially if there is no collateral. The lender, on the other hand, has no possibility to assess the risk of a loan to a new client. This raises the business risk substantially. However, if there is an exchange of information among these institutions, two types can be distinguished. First, only negative information about loan loss and payment default is shared. The compilation of a blacklist helps MFIs to exclude problematic borrowers from their loan portfolio. The filter effect mars the problem of negative selection. The fact that borrowers want to avoid their names appearing on this blacklist reduces the moral hazard in connection with the loan repayment. The second and more comprehensive form of information exchange features both positive and more negative data on the borrower. The whitelist with the positive data comprises data concerning all of the borrower's outstanding and past loans. This allows borrowers to create a flawless credit history for themselves – often in the form of a creditworthiness rating – and therefore facilitate access to further loans. MFIs on the other hand, can benefit from the fact that they can reduce their credit risk by a better assessment of their borrowers.26

The arrival of credit bureaus is generally regarded positively. The exchange of information among the different institutions not only mars the risk of over‐indebtedness in borrowers but it also lowers the default rates, which in a competitive market environment inevitably leads to lower interest on loans. In the 1990s, many Asian and Latin American countries saw the launch of efficient and effective credit information systems that contributed substantially towards the stability of local financial systems. Africa has the least developed credit information systems. The swift growth of African financial markets in the recent past has, however, generated an enormous interest in a potential introduction of these systems.27

5.6 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

Microfinance institutions are crucial because they are responsible for the supply of services to micro entrepreneurs. Loan granting, deposit taking, and the wide range of non‐financial services are not only the stepping stones to financial integration of the world's most destitute, but they also contribute sustainably towards the fight against poverty worldwide.

Depending on their level of development and grade of commercialization, MFIs can be put into three categories (tiers 1, 2 and 3): Tier 1 contains established MFIs that have formal structures and that are predominantly state‐regulated banks that are rated by rating agencies. Tier 2 MFIs are smaller and less established institutions undergoing a transformation up to regulated banks. Tier 3 institutions are either on the verge of profitability or are non‐profit‐oriented and pursue social goals. MFIs are largely funded via local means, but a sizable share of their funds comes from foreign investors – be it in the form of external capital or equity. Especially in the context of microfinance as a driving force in the development of local financial markets, the current trend towards raising capital locally is a much hailed development.

In the wake of the rather rapid development of the global microfinance sector, the aspect of regulation must not be neglected. MFIs should be subject to financial regulation and be supervised on a regular basis. In this way, crises can be averted and financial transactions upheld. More importantly, regulation of the microfinance sector promotes competition and efficiency in the finance sector and protects clients and their deposits in the long run. For this reason, the development of central loan offices as an industry standard is positive. Loan offices promote the exchange of information between the different MFIs and the authorities, mitigate the issue of client default and in a competitive environment lower default rates and interest rates in equal measure.