CHAPTER 15

Capturing Learning from Innovation

One of the common metaphors used to describe innovation is that of a journey – a complex, fitful travel through uncertain territory involving false starts, wrong directions, blind alleys, and unexpected problems. Successful innovation implies the completion of this risky adventure and – through widespread adoption and diffusion of the new idea as a product, service, or process – a happy ending with valuable returns on the original investment. But it also provides an opportunity to reflect on the journey and to take stock of the knowledge acquired through an often difficult experience. It’s worth doing this because the knowledge gained through such reflection can provide a powerful resource to help with the next innovation journey.

Not all innovation is, of course, successful – but the opportunities for learning from failure are also considerable. Understanding what doesn’t work on a technological level, or recognizing the difficulties in a particular marketplace, which led to nonadoption, is useful information to take stock of and use when planning the next expedition. Experience is an excellent teacher – but its lessons will only be of value if there is a systematic and committed attempt to learn them.

This chapter reviews the ways in which learning can be captured from the innovation experience.

15.1 What We Have Learned About Managing Innovation

It will be useful to briefly take stock of the key themes we have been covering in the book. We can summarize these as follows:

- Learning and adaptation are essential in an inherently uncertain future – so innovation is an imperative.

- Innovation is about interaction of technology, market, and organization.

- Innovation can be linked to a generic process that all enterprises – public and private sectors – have to find their way through.

- Routines are learned patterns of behavior, which become embodied in structures and procedures over time. As such, they are hard to copy and highly firm-specific.

- Innovation management is the search for effective routines – in other words, it is about managing the learning process toward more effective routines to deal with the challenges of the innovation process.

We have also argued that innovation management is not a matter of doing one or two things well, but about good all-round performance. There are no, single, simple magic bullets but a set of learned behaviors. In particular, we have identified four clusters of behavior, which we feel represent particularly important routines. Successful innovation:

- is strategy-based;

- depends on effective internal and external linkages;

- requires effective enabling mechanisms for making change happen;

- only happens within a supporting organizational context.

In the strategy domain, there are no simple recipes for success but a capacity to learn from experience and analysis is essential. Research and experience point to three essential ingredients in innovation strategy:

- The position of the firm, in terms of its products, processes, technologies, and the national innovation system in which it is embedded. Although a firm’s technology strategy may be influenced by a particular national system of innovation, it is not determined by it.

- The technological paths open to the firm, given its accumulated competencies. Firms follow technological trajectories, each of which has distinct sources and directions of technological change and which define key tasks for strategy.

- The organizational processes followed by the firm in order to integrate strategic learning across functional and divisional boundaries.

Within the area of linkages, developing close and rich interaction with markets, with suppliers of technology and other organizational players, is of critical importance. Linkages offer opportunities for learning – from tough customers and lead users, from competitors, from strategic alliances, and from alternative perspectives. The theme of “open innovation” is increasingly becoming recognized as relevant to an era in which networking and open collective innovation are the dominant mode.

In order to succeed, organizations also need effective implementation mechanisms to move innovations from idea or opportunity through to reality. This process involves systematic problem-solving and works best within a clear decision-making framework, which should help the organization to stop projects as well as to progress development if things are going wrong. It also requires skills in project management and control under uncertainty and parallel development of both the market and the technology streams. And it needs to pay attention to managing the change process itself, including anticipating and addressing the concerns of those who might be affected by the change.

Finally, innovation depends on having a supporting organizational context in which creative ideas can emerge and be effectively deployed. Building and maintaining such organizational conditions are a critical part of innovation management and involve working with structures, work organization arrangements, training and development, reward and recognition systems, and communication arrangements. Above all, the requirement is to create the conditions within which a learning organization can begin to operate, with shared problem identification and solving and with the ability to capture and accumulate learning about technology and about management of the innovation process.

Throughout the book, we have tried to consider the implications of managing innovation as a generic process but also to look at the ways in which approaches need to take into account two key challenges in the twenty-first century – those of managing “beyond the steady state” and “beyond boundaries.” The same basic recipe still applies, but there is a need to configure established approaches and to learn to develop new approaches to deal with these challenges.

15.2 How to Build Dynamic Capability

To build dynamic capability, we need to focus on two dimensions of learning.

First, there is the acquisition of new knowledge to add to the stock of knowledge resources that the organization possesses. These can be technological or market knowledge, understanding of regulatory and competitive contexts, and so on. As we’ve seen throughout the book, innovation represents a key strategy for developing and sustaining competitiveness in what are increasingly “knowledge economies” – but being able to deploy this strategy depends on continuing accumulation, assimilation, and deployment of new knowledge. Firms that exhibit competitive advantage – the ability to win and to do so continuously – demonstrate “timely responsiveness and rapid product innovation, coupled with the management capability to effectively co-ordinate and redeploy internal and external competencies” [1].

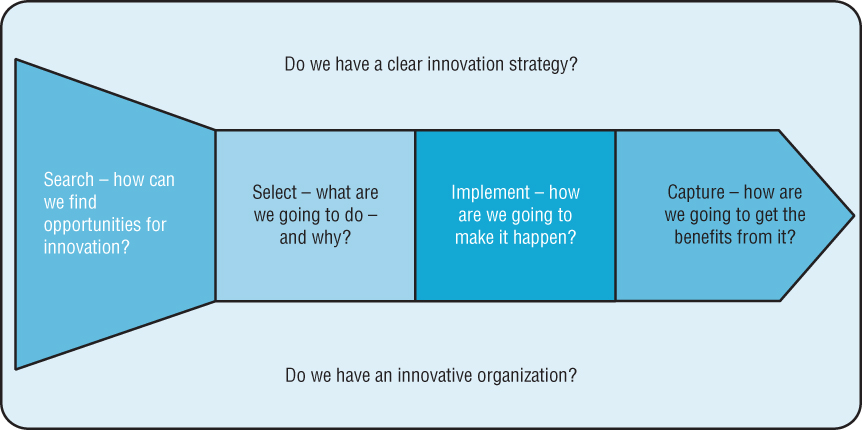

And second, there is knowledge about the innovation process itself – the ways in which it can be organized and managed, the bundle of routines that enable us to plan and execute the innovation journey. Figure 15.1 reminds us of the model we have been using as an explanatory framework, and “innovation capability” refers to our ability to create and operate such a framework in our organizations.

FIGURE 15.1 Simplified model of the innovation process.

But in a constantly changing environment, that capability may not be enough – faced with moving targets along several dimensions (markets, technologies, sources of competition, regulatory rules of the game), we have to be able to adapt and change our framework. This process of constant modification and development of our innovation capability – adding new elements, reinforcing existing ones, and sometimes letting go of older and no longer appropriate ones – is the essence of what is called “dynamic capability” [1].

The lack of such capability can explain many failures, even among large and well-established organizations. For example, the problem of:

- failing to recognize or capitalize on new ideas that conflict with an established knowledge set – the “not invented here” problem [2];

- being too close to existing customers and meeting their needs too well – and not being able to move into new technological fields early enough [3];

- adopting new technology – following technological fashions – without an underlying strategic rationale [4];

- lacking codification of tacit knowledge [5].

The costs of not managing learning – of lacking dynamic capability – can be high. At the least, it implies a blunting of competitive edge, a slipping against previously strong performance. In some cases, the fall accelerates and eventually leads to terminal decline – as the fate of companies such as Digital, Polaroid, or Swissair, once feted for their innovative prowess, indicates. In others – such as IBM – there is a complete rethink and reinvention of the business, radically changing the operating routines and allowing new models to emerge. For others – such as Nokia – the process of reinvention continues, having moved from being a sprawling conglomerate linked to timber and paper to being dominant in mobile phone handsets to now playing a key role in providing the network infrastructure for the digital world.

So we need to look hard at the ways in which organizations can learn – and how they do so in conscious and strategic fashion. In other words, how do they learn to learn? This is why routines play such an important role in managing innovation – they represent the firm-specific patterns of behaviors that enable a firm to solve particular problems [6]. They embody what an organization (and the individuals within it) has captured from their experience about how to learn.

15.3 How to Manage Innovation

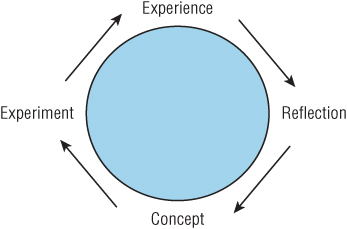

We can think of the innovation process shown in Figure 15.1 as a learning loop – picking up signals that trigger a response. As we’ve suggested, organizations should undertake some form of review of innovation projects in order to help them develop both technological and managerial capabilities [7]. One way of representing the learning process that can take place in organizations is to use a simple model of a learning cycle based on the work of David Kolb (Figure 15.2).

FIGURE 15.2 Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning.

Here learning is seen as requiring the following [8]:

- Structured and challenging reflection on the process – what happened, what worked well, what went wrong, and so on

- Conceptualization – capturing and codifying the lessons learned into frameworks and eventually procedures to build on lessons learned

- Experimentation – the willingness to manage things differently next time, to see if the lessons learned are valid

- Honest capture of experience (even if this has been a costly failure) so we have raw material on which to reflect

Effective learning from and about innovation management depends on establishing a learning cycle around these themes. In that sense, it is an “adaptive” learning system, helping the organization survive and grow within its environment. But making sure that this adaptive system works well also requires a second learning loop, one that can “reprogram” the system to tune it better to a changing environment and as a result of lessons learned about how well it works. (It’s a little like a central heating or air-conditioning system – there is an adaptive loop that responds when the temperature gets hotter or colder in the room by modifying the output of the heater or air-conditioning unit. But we also need someone to think about – and reset – the thermostat to suit the changing conditions.) This kind of “double loop” or generative learning is at the heart of the innovation management challenge [9–11]. How can we periodically step back and review how well the overall system is working and adapt it to new circumstances? This is the challenge of building “dynamic capability.”

We should also recognize the problem of unlearning. Not only is learning to learn a matter of acquiring and reinforcing new patterns of behavior – it is often about forgetting old ones [12]. Letting go in this way is by no means easy, and there is a strong tendency to return to the status quo or equilibrium position – which helps account for the otherwise surprising number of existing players in an industry who find themselves upstaged by new entrants taking advantage of new technologies, emerging markets of new business models. Managing discontinuous innovation requires the capacity to cannibalize and look for ways in which other players will try and bring about “creative destruction” of the rules of the game. Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric, is famous for having sent out a memo to his senior managers asking them to tell him how they were planning to destroy their businesses! The intention was not, of course, to execute these plans, but rather to use the challenge as a way of focusing on the need to be prepared to let go and rethink – to unlearn [13]. In his studies of the shipbuilding division of Hyundai, Linsu Kim talks about the powerful approach of “constructed crisis” – creating a sense of urgency and challenge, which allows for both learning and unlearning to take place [14]. And Dorothy Leonard warns against the complacency that comes when “core competencies” become “core rigidities” – and block the organization form seeing or acting on urgent signals for change [15].

15.4 The Importance of Failure

No organization or individual starts with a fully developed version shown in Figure 15.1. We learn and adapt our approach, building capability through a process of trial and error, gradually improving our skills as we find what works for us. These “behavioral routines” become embedded in “the way we do things around here”; they reflect our approach to managing innovation.

We need to recognize the importance of failure in this. Innovation is all about trying new things out – and they may not always work. Experimentation and testing, prototyping and pivoting are all part and parcel of the innovation story, and it is through this process that we gradually build capability.

Case Study 15.1 looks at the role of failure as a support for learning.

Most smart innovators recognize that failure comes with the innovation territory. “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs” is as good a motto as any to describe a process that by its very nature involves experimentation and learning. Typically, organizations work on the assumption that of 100 new product ideas, only a handful will make it through to success in the marketplace, and they are comfortable with that because the process of failing provides them with rich new insights, which help them refocus and sharpen their next efforts.

Entrepreneurs face the same challenge in starting up a new venture. It’s impossible to predict how a market will react, how technologies will behave, how new business models will gain acceptance, and so the approach is one of experimentation around a core idea. Feedback from carefully designed experiments allows the venture to pivot, to move around the core focus to get closer to the viable idea, which will work.

The problem is not with failure – innovations will often fail since they are experiments, steps into the unknown. It’s with failing to learn from those experiences.

Failure is important in at least three ways in innovation:

- It provides insights about what not to do. In a world where you are trying to pioneer something new, there are no clear paths, and instead, you have to cut and hack your own way through the jungle of uncertainty. Inevitably, there is a risk that the direction you chose was wrong, but that kind of “failure” helps identify where not to work, and this focusing process is an important feature in innovation.

- Failure helps build capability – learning how to manage innovation effectively comes from a process of trial and error. Only through this kind of reflection and revision can we develop the capability to manage the process better next time around. Anyone might get lucky once, but successful innovation is all about building a resilient capability to repeat the trick. Taking time out to review projects is a key factor in this – if we are honest, we learn a lot more from failure than from success. Well-managed postproject reviews where the aim is to learn and capture lessons for the future rather than apportion blame are important tools for improving innovation management.

- Failure helps others learn and build capability. Sharing failure stories – a kind of “vicarious learning” – provides a road map for others, and in the field of capability building that’s important. Not for nothing do most business schools teach using the case method – stories of this kind carry valuable information, which can be applied elsewhere.

Experienced innovators know this and use failure as a rich source of learning. Most of what we’ve learned from innovation research has come from studying and analyzing what went wrong and how we might do it better next time – Robert Cooper’s work on stage gates, NASA’s development of project management tools, Toyota’s understanding of the minute trial-and-error learning loops, which their kaizen system depends upon and which have made it the world’s most productive carmaker [16,17]. Google’s philosophy is all about “perpetual beta” – not aiming for perfection but allowing for learning from its innovation. And IDEO, the successful design consultancy, has a slogan that underlines the key role learning through prototyping plays in their projects – “fail often, to succeed sooner!” Failure is also built into models of “agile innovation”; here the challenge is in making sure the experimental loops and learning capture are part of a system of “intelligent failure” [18–20].

So rather than seeing failure in innovation as a problem, we should see it as an important resource – as long as we learn from it.

15.5 Tools to Help Capture Learning

If we are to extract useful learning from successful – or unsuccessful – innovation activities, then we need to look at the range of tools that might help us with the task. In the following section, we’ll briefly look at some of the possible approaches to this task.

Postproject Reviews (PPRs)

Postproject reviews (PPRs) are structured attempts to capture learning at the end of an innovation project – for example, in a project debrief. This is an optional stage, and many organizations fail to carry out any kind of review, simply moving on to the next project and running the risk of repeating the mistakes made in the previous projects. Others do operate some form of structured review or postproject audit; however, this does not of itself guarantee learning since emphasis may be more on avoiding blame and trying to cover up mistakes.

On the positive side, they work well when there is a structured framework against which to examine the project, exploring the degree to which objectives were met, the things that went well and those that could be improved, the specific learning points raised, and the ways in which they can be captured and codified into procedures that will move the organization forward in terms of managing technology in future [21].

But such reviews depend on establishing a climate in which people can honestly and objectively explore issues that the project raises. For example, if things have gone badly, the natural tendency is to cover up mistakes or try and pass the blame around. Meetings can often degenerate into critical sessions with little being captured or codified for use in future projects.

The other weakness of PPRs is that they are best suited to distinct projects – for example, developing a new product or service or implementing a new process [22]. They are not so useful for the smaller-scale, regular incremental innovation, which is often the core of day-to-day improvement activity. Instead, we need some form of systematic capture. Variations on the standard operating procedures approach can be powerful ways of capturing learning – particularly in translating it from tacit and experiential domains to more codified forms for use by others [23]. They can be simple – for example, in many Japanese plants working on “total productive maintenance” programs, operators are encouraged to document the operating sequence for their machinery. This is usually a step-by-step guide, often illustrated with photographs and containing information about “know-why” as well as “know-how.” This information is usually contained on a single sheet of paper and displayed next to the machine. It is constantly being revised as a result of continuous improvement activities, but it represents the formalization of all the little tricks and ideas that the operators have come up with to make that particular step in the process more effective [24].

On a larger scale, capturing knowledge into procedures also provides a structured framework within which to operate more effectively. Increasingly, organizations are being required by outside agencies and customers to document their processes and how they are managed, controlled, and improved – for example, in the quality area under ISO 9000, in the environmental area under ISO 14000, and in an increasing number of customer/supplier initiatives such as Ford’s QS9000.

Once again, there are strengths and weaknesses in using procedures as a way of capturing learning. On the plus side, there is much value in systematically trying to reflect on and capture knowledge derived from experience – it is the essence of the learning cycle. But it only works if there is commitment to learning and a belief in the value of the procedures and their subsequent use. Otherwise, the organization simply creates procedures that people know about but do not always observe or use. There is also the risk that, having established procedures, the organization then becomes resistant to changing them – in other words, it blocks out further learning opportunities.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is the general name given to a range of techniques that involve comparisons – for example, between two variants of the same process or two similar products – so as to provide opportunities for learning [25–27]. Benchmarking can, for example, be used to compare how different companies manage the product development processes; where one is faster than the other, there are learning opportunities in trying to understand how they achieve this [28].

Benchmarking works in two ways to facilitate learning. First, it provides a powerful motivator since comparison often highlights gaps, which – if they are not closed – might well lead to problems in competitiveness later. In this sense, it offers a structured methodology for learning and is widely used by external agencies who see it as a lever with which to motivate particularly smaller enterprises to learn and change [29]. It provides a powerful focus for the operation of “learning networks” (described in Chapter 7), since it offers a framework around which shared learning can be targeted and monitored and across which experiences can be exchanged [30].

But benchmarking also provides a structured way of looking at new concepts and ideas. It can take several forms, between similar activities

- within the same organization;

- in different divisions of a large organization;

- in different firms within a sector;

- in different firms and sectors.

The last group is often the most challenging since it brings completely new perspectives. By looking at, for example, how a supermarket manages its supply chain, a manufacturer can gain new insights into logistics. By looking at how an engineering shop can rapidly set up and change over between different products can help a hospital use its expensive operating theaters more effectively.

For example, Southwest Airlines achieved an enviable record for its turnaround speed at airport terminals. It drew inspiration from watching how industry carried out rapid changeover of complex machinery between tasks – and, in turn, those industries learned from watching activities such as pit-stop procedures in the Grand Prix motor racing world. In a similar fashion, dramatic productivity and quality improvements have been made in the health-care sector, drawing on lessons originating in inventory management systems in manufacturing and retailing [31].

Capability Maturity Models

Building on the success of benchmarking as an organizational development tool, there has been increasing use of capability maturity models [32]. The origin of the term came from software projects where it became clear that success – in terms of delivering regularly on time, within budget, and with low error rates was not an accident – it resulted from a learned and developed capability. In such models, the auditing and reviewing process in benchmarking is done against ideal-type or normative models of good practice. Such an approach found particular expression during the “quality revolution” of the 1990s, where benchmarking frameworks such as the Malcolm Baldrige Award in the United States, the Deming Prize in Japan, and the European Quality Award all used sophisticated benchmarking frameworks [33]. The approach has been extended to a number of other domains – for example, software development processes, project management, IT implementation, and new product development [32]. It has been used by policymakers aiming to upgrade performance in key sectors – for example, in the United Kingdom, a framework for benchmarking and auditing manufacturing performance was developed and offered as a national service, with special emphasis on assisting smaller firms improve their performance [34,35].

Agile Innovation Methods

Agile innovation methods also make extensive use of a formal learning cycle. Whether in projects within established organizations or as part of the “lean start-up” approach, the core idea is controlled experimentation. Hypotheses are developed and tested, and the resulting feedback used to help learn how to target and manage the innovation development, using concepts such as pivoting to support the approach [19,20].

15.6 Innovation Auditing

In thinking about innovation management, we can draw an analogy with financial auditing where the health of the company and its various operations can be seen through auditing its books. The principle is simple: using what we know about successful and unsuccessful innovation and the conditions that bring it about, we can construct a checklist of questions to ask of the organization. We can then score its performance against some model of “best practice” and identify where things could be improved.

This auditing approach has considerable potential relevance for the practice of innovation management, and a number of frameworks have been developed to support it. Back in the 1980s, the UK National Economic Development Office developed an “innovation management tool kit,” which has been updated and adapted for use as part of a European program aimed at developing better innovation management among small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Another framework, originally developed at London Business School, was promoted by the UK Department of Trade and Industry. Others include the “living innovation” model, which was jointly promoted with the Design Council [34,36], and various innovation frameworks promoted by trade and business associations. Francis offers an overview of a number of these [37]. This tradition has continued with the work of NESTA in the United Kingdom, which has commissioned a variety of studies to help develop an “Innovation Index,” offering a measurement framework for both practice and performance in innovation [38].

Other frameworks that cover particular aspects of innovation management, such as creative climate, continuous improvement, and product development, have been developed [39–41]. With the increasing use of the Internet have come a number of sites that offer interactive frameworks for assessing innovation management performance as a first step toward organization development.

In each case, the purpose of such auditing is not to score points or win prizes but to enable the operation of an effective learning cycle through adding the dimension of structured reflection. It is the process of regular review and discussion, which is important rather than detailed information or exactness of scores. The point is not simply to collect data but to use these measures to drive improvement of the innovation process and the ways in which it is managed. As the quality guru, W. Edwards Deming, pointed out, “If you don’t measure it you can’t improve it!”

There are typically two dimensions of interest in carrying out such an “innovation audit”:

- How well do we perform in terms of innovation results?

- How well do we manage (in terms of the underlying capability to repeat the innovation trick)?

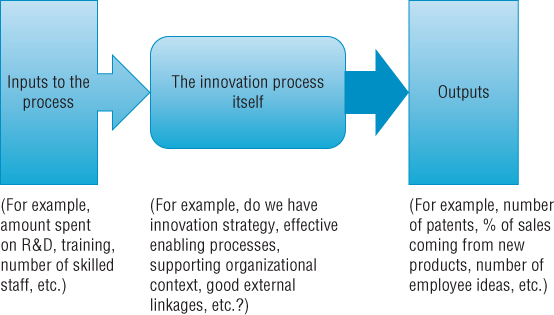

Figure 15.3 indicates the range of measures that we might put in place, covering the inputs and outputs of the process together with our core interest, how the process itself is organized and managed. An overview of such approaches is given by Richard Adams and colleagues [42].

FIGURE 15.3 Outline framework for innovation measurement.

15.7 Measuring Innovation Performance

Two sets of measures represent things we could count and evaluate as indicators of innovation – how much we put in (time, money, skilled resources, etc.) and what the outputs from the process are.

Inputs to the innovation process are important – if we don’t spend any time or money, or invest in skilled staff and their further development, then we are unlikely to be able to operate a systematic process to generate ideas and translate them into innovations that create value. Possible indicators here might include spending on R&D or market research, investment in training and development, or the percentage of skilled scientists and engineers on the staff. More subtle but potentially interesting measures might include the amount spent on open-ended or “blue-sky” exploration compared with “mainstream” innovation activities, or the diversity of the backgrounds of staff recruited to help with the process.

In reviewing outputs – innovative performance – we can again look at a number of possible measures and indicators. For example, we could count the number and range of patents and scientific papers as indicators of knowledge produced or the number of new products introduced (and percentage of sales and/or profits derived from them) as indicators of product innovation success [43]. And we could use measures of operational or process elements, such as customer satisfaction surveys to measure and track improvements in quality or flexibility [29,44]. We can also try to assess the strategic impact where the overall business performance is improved in some way and where at least some of the benefits can be attributed directly or indirectly to innovation – for example, growth in revenue or market share, improved profitability, higher value added [45].

Interestingly, recent attempts to develop different output measures of innovation performance have highlighted the previously “hidden” innovation potential in sectors such as the creative industries, professional services, or advertising [46,47].

We could also consider a number of more specific performance measures of the internal workings of the innovation process or particular elements within it. For example, we could monitor the number of new ideas (product/service/process) generated at the start of innovation system, failure rates – in the development process, in the marketplace, or the number or percentage of overruns on development time and cost budgets. In process innovation, we might look at the average lead time for introduction or use measures of continuous improvement – suggestions/employee, number of problem-solving teams, savings accruing per worker, cumulative savings, and so on.

15.8 Measuring Innovation Management Capability

In reviewing how well our innovation operates, we could look at the ways in which the process itself is organized and managed. The core questions in our process model are relevant here:

- How well do we search for opportunities?

- How well do we manage the selection process?

- How well do we manage implementation of innovation projects, from inception to launch and beyond?

- Do we have a supportive innovative organization?

- Do we have a clear and communicated innovation strategy?

- Do we build and maintain rich and diverse external linkages?

- How well do we capture learning from the innovation process?

There are various measures that we could apply to support reflection and analysis around these questions. In each chapter of the book, we have tried to present checklists and frameworks for thinking about these questions – for example, how good is the “creative climate” of the organization or how well strategy is deployed and communicated [40]. It’s also important to use such frameworks as a starting point for more focused exploration. Throughout the book, we have stressed that while the challenge in innovation management is generic, there are specific issues around which specific responses need to be configured.

We might, for example, look at the case of service innovation and focus our audit questions around themes that might be particularly relevant in thinking about managing such innovation. See Box 15.1 for a discussion of five components involved in measuring service innovation.

Similarly, we have been arguing that there are conditions – beyond the steady state – where we need to take a different approach to managing innovation and to introduce new or at least complementary routines to those helpful in dealing with “steady-state” innovation. Again we can develop specific audit questions to help facilitate this kind of reflection, and the website has an example of such a framework. Or we could consider different stages in the life cycle of the organization – for example, there is a tool to aid reflection around key questions for start-up entrepreneurs on the website.

We can also develop audits for particular aspects of the innovation process – for example, is there a “creative climate” within which ideas can flourish and be built upon? Or are there structures and processes in place to enable high involvement of employees in the innovation process? Are there conditions – beyond the steady state – where we need to take a different approach to managing innovation and to introduce new or at least complementary routines to those helpful in dealing with “steady-state” innovation?

Table 15.1 summarizes some structured frameworks around these themes.

TABLE 15.1 Audit Frameworks to Support Capability Development

| Key Questions and Issues in Managing Innovation | Reflection and Development Aids Available on Website |

| How well do we manage innovation? | Innovation audit |

| How well do we manage service innovation? | Service innovation (STARS) framework |

| Start-up phase for new ventures | Entrepreneurs checklist |

| Do we engage our employees fully in innovation? | High-involvement innovation audit |

| How well do we manage discontinuous innovation? | Discontinuous innovation audit |

| How widely do we search in an open-innovation world? | Search strategies audit |

| Do we have a creative climate for innovation? | Creative climate review |

| Can we make the most of external knowledge for innovation? | Absorptive capacity review |

| How effective are our selection processes for innovation? | Selection audit |

| Do we have a clear innovation strategy – and is it communicated and deployed? | Innovation strategy audit |

15.9 Reflections

In this section, we give some examples of reflecting on the innovation process in any organization.

Search

There are many approaches that an organization could take to managing the challenge of finding opportunities to trigger the innovation process. How well it does it is another matter – but one way we could tell might be to listen to the things people said in describing “the way we do things around here” – in other words, the pattern of behavior and beliefs that creates the climate for innovation.

And if we walked around the organization, we’d expect to hear people talking about the methods they actually use. We should hear things such as around here…

- We have good “win-win” relationships with our suppliers and we pick up a steady stream of ideas from them.

- We are good at understanding the needs of our customers/end users.

- We work well with universities and other research centers to help us develop our knowledge.

- Our people are involved in suggesting ideas for improvements to products or processes.

- We look ahead in a structured way (using forecasting tools and techniques) to try and imagine future threats and opportunities.

- We systematically compare our products and processes with other firms.

- We collaborate with other firms to develop new products or processes.

- We try to develop external networks of people who can help us – for example, with specialist knowledge.

- We work closely with ”lead users” to develop innovative new products and services.

Of course, part of the search question is about picking up rather weak signals about emerging – and sometimes radically different – triggers for innovation. So to deal with the unexpected, people in smart firms might also say things such as around here…

- We deploy “probe and learn” approaches to explore new directions in technologies and markets.

- We make connections across industry to provide us with different perspectives.

- We have mechanisms to bring in fresh perspectives – for example, recruiting from outside the industry.

- We use make regular use of formal tools and techniques to help us think “out of the box.”

- We focus on “next practices” as well as “best practices.”

- We use some form of technology scanning/intelligence gathering – we have well-developed technology antennae.

- We work with “fringe” users and very early adopters to develop our new products and services.

- We use technologies such as the Web to help us become more agile and quick to pick up on and respond to emerging threats and opportunities on the periphery.

- We deploy “targeted hunting” around our periphery to open up new strategic opportunities.

- We are organized to deal with “off-purpose” signals (not directly relevant to our current business) and don’t simply ignore them.

- We have active links into long-term research and technology community – we can list a wide range of contacts.

- We recognize users as a source of new ideas and try and “coevolve” new products and services with them.

Select

If we visited a smart organization, we’d expect to find that people we approached would tell us things such as around here…

- We have a clear system for choosing innovation projects, and everyone understands the rules of the game in making proposals.

- When someone has a good idea, they know how to take it forward.

- We have a selection system, which tries to build a balanced portfolio of low- and high-risk projects.

- We focus on a mixture of product, process, market, and business model innovation.

- We balance projects for “do better” innovation with some efforts on the radical, “do different” side.

- We recognize the need to work “outside the box,” and there are mechanisms for handling “off message” but interesting ideas.

- We have structures for corporate venturing.

Implement

And when it comes to just “getting it done,” we would expect to hear things such as around here…

- We have clear and well-understood formal processes in place to help us manage new product development effectively from idea to launch.

- Our innovation projects are usually completed on time and within budget.

- We have effective mechanisms for managing process change from idea through to successful implementation.

- We have mechanisms in place to ensure early involvement of all departments in developing new products/processes.

- There is sufficient flexibility in our system for product development to allow small “fast track” projects to happen.

- Our project teams for taking innovation forward involve people from all the relevant parts of the organization.

- We involve everyone with relevant knowledge from the beginning of the process.

We’d also expect them to have some provision for the wilder and more radical kind of project, which might need to go on a rather different route in making its journey. People might say about things such as around here…

- We have alternative and parallel mechanisms for implementing and developing radical innovation projects, which sit outside the “normal” rules and procedures.

- We have mechanisms for managing ideas that don’t fit our current business – for example, we license them out or spin them off.

- We make use of simulation, rapid prototyping tools, and so on to explore different options and delay commitment to one particular course.

- We have strategic decision-making and project selection mechanisms, which can deal with more radical proposals outside of the mainstream.

- There is sufficient flexibility in our system for product development to allow small “fast track” projects to happen.

Statements we’d expect to hear around such a strategically focused and led organization might include around here…

- People in this organization have a clear idea of how innovation can help us compete.

- There is a clear link between the innovation projects we carry out and the overall strategy of the business.

- We have processes in place to review new technological or market developments and what they mean for our firm’s strategy.

- There is top management commitment and support for innovation.

- Our top team have a shared vision of how the company will develop through innovation.

- We look ahead in a structured way (using forecasting tools and techniques) to try and imagine future threats and opportunities.

- People in the organization know what our distinctive competence is – what gives us a competitive edge.

- Our innovation strategy is clearly communicated, so everyone knows the targets for improvement.

And we’d also expect some stretching strategic leadership, getting the organization to think well outside its box and anticipate very different challenges for the future – expressed in statements such as around here…

- Management creates “stretch goals” that provide the direction but not the route for innovation.

- We actively explore the future, making use of tools and techniques such as scenarios and foresight.

- We have capacity in our strategic thinking process to challenge our current position – we think about “how to destroy the business”!

- We have strategic decision-making and project selection mechanisms, which can deal with more radical proposals outside of the mainstream.

- We are not afraid to “cannibalize” things we already do to make space for new options.

If we visited such an organization, we’d find evidence of these approaches being used widely and people would say things such as around here…

- Our organization structure does not stifle innovation but helps it to happen.

- People work well together across departmental boundaries.

- There is a strong commitment to training and development of people.

- People are involved in suggesting ideas for improvements to products or processes.

- Our structure helps us to take decisions rapidly.

- Communication is effective and works top down, bottom up, and across the organization.

- Our reward and recognition system supports innovation.

- We have a supportive climate for new ideas – people don’t have to leave the organization to make them happen.

- We work well in teams.

We’d also find a recognition that one size doesn’t fit all and that innovative organizations need the capacity – and the supporting structures and mechanisms – to think and do very different things from time to time. So we’d also expect to find people saying things such as around here…

- Our organization allows some space and time for people to explore “wild” ideas.

- We have mechanisms to identify and encourage “intrapreneurship” – if people have a good idea, they don’t have to leave the company to make it happen.

- We allocate a specific resource for exploring options at the edge of what we currently do – we don’t load everyone up 100%.

- We value people who are prepared to break the rules.

- We have high involvement from everyone in the innovation process.

- Peer pressure creates a positive tension and creates an atmosphere to be creative.

- Experimentation is encouraged.

Proactive Links

If we were to visit a successful innovative player, we’d get a sense of how far they had developed these capabilities for networking by asking around. People would typically say things such as around here…

- We have good “win-win” relationships with our suppliers.

- We are good at understanding the needs of our customers/end users.

- We work well with universities and other research centers to help us develop our knowledge.

- We work closely with our customers in exploring and developing new concepts.

- We collaborate with other firms to develop new products or processes.

- We try to develop external networks of people who can help us – for example, with specialist knowledge.

- We work closely with the local and national education system to communicate our needs for skills.

- We work closely with “lead users” to develop innovative new products and services.

And there would be some evidence of their increasing efforts to create wide-ranging “open-innovation”-type links – with statements such as around here…

- We make connections across industry to provide us with different perspectives.

- We have mechanisms to bring in fresh perspectives – for example, recruiting from outside the industry.

- We have extensive links with a wide range of outside sources of knowledge – universities, research centers, specialized agencies, and we actually set them up even if not for specific projects.

- We use technology to help us become more agile and quick to pick up on and respond to emerging threats and opportunities on the periphery.

- We have “alert” systems to feed early warning about new trends into the strategic decision-making process.

- We practice “open innovation” – rich and widespread networks of contacts from whom we get a constant flow of challenging ideas.

- We have an approach to supplier management, which is open to strategic “dalliances.”

- We have active links into long-term research and technology community – we can list a wide range of contacts.

- We recognize users as a source of new ideas and try and “coevolve” new products and services with them.

Learning

Smart firms actively manage their learning – and the kinds of things people might say in such organizations would be that around here…

- We take time to review our projects to improve our performance next time.

- We learn from our mistakes.

- We systematically compare our products and processes with other firms.

- We meet and share experiences with other firms to help us learn.

- We are good at capturing what we have learned so that others in the organization can make use of it.

- We use measurement to help identify where and when we can improve our innovation management.

- We learn from our periphery – we look beyond our organizational and geographical boundaries.

- Experimentation is encouraged.

15.10 Developing Innovation Capability

A great deal of research effort has been devoted to the questions of what and how to measure in innovation. The risk is that we become so concerned with these questions that we lose sight of the practical objective, which is to reflect upon and improve the management of the process. The format of any particular audit tool is not important; what is needed is the ability to use it to make a wide-ranging review of the factors affecting innovation success and failure and how management of the process might be improved. It offers:

- an audit framework to see what the organization did right and wrong in the case of particular innovations or as a way of understanding why things happened the way they did;

- a checklist to see if they are doing the right things;

- a benchmark to see if they are doing them as well as others;

- a guide to continuous improvement of innovation management;

- a learning resource to help acquire knowledge and provide inspiration for new things to try;

- a way of focusing on subsystems with particular problems and then working with the owners of those processes and their customers and suppliers to see if the discussion cannot improve on things.

So, for example, an organization with no clear innovation strategy, with limited technological resources, and no plans for acquiring more, with weak project management, with poor external links, and with a rigid and unsupportive organization would be unlikely to succeed in innovation. By contrast, one that was focused on clear strategic goals had developed long-term links to support technological development, had a clear project management process, that was well supported by senior management, and that operated in an innovative organizational climate would have a better chance of success.

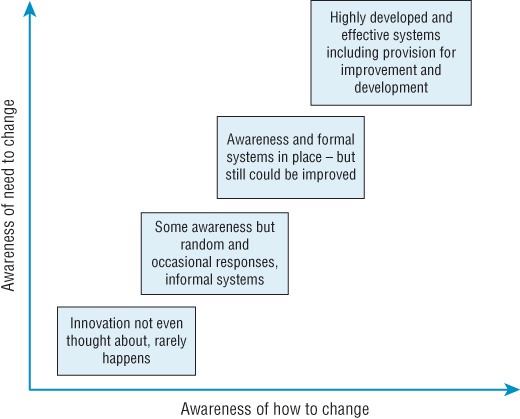

Figure 15.4 gives an example of a framework for thinking about developing innovation management capability.

FIGURE 15.4 Developing innovation management capability.

Of course, no organization starts with a perfectly developed capability to organize and manage innovation. It undertakes the process of trial-and-error learning, slowly finding out which behaviors work and which do not and gradually repeating and reinforcing them into a pattern of “routines.” Developing innovation capability involves establishing and reinforcing those routines and reviewing and checking that they are still appropriate or whether they need replacing or modifying. View 15.1 gives some examples of these reflection points. Some useful key questions are as follows:

- What do we need to do more of, strengthen?

- What do we need to do less of, or stop?

- What new routines do we need to develop?

15.11 Final Thoughts

We have repeatedly said that innovation is complex, uncertain, and almost (but not quite) impossible to manage. That being so, we can be sure that there is no such thing as the perfect organization for innovation management; there will always be opportunities for experimentation and continuous improvement. As we have suggested throughout the book, the challenge is to constantly review and reconfigure in the light of changing circumstances – whether discontinuous “beyond the steady state” innovation or in the context of “open innovation where the challenge is working beyond the boundaries.” In the end, innovation management is not an exact or predictable science but a craft, a reflective practice in which the key skill lies in reviewing and configuring to develop dynamic capability.

Throughout the book, we have tried to consider the implications of managing innovation as a generic process but also to look at the ways in which approaches need to take into account two key challenges in the twenty-first century – those of managing “beyond the steady state” and “beyond boundaries.” The same basic recipe still applies, but there is a need to configure established approaches and to learn to develop new approaches to deal with these challenges.

Summary

In this chapter, we have looked at the ways in which organizations can capture learning and build capability in innovation management. The major requirement is for a commitment to undertake such learning, but it can also be enabled by the use of tools and reflection aids. In particular, the chapter looks at various approaches to innovation auditing and offers some templates for reviewing and developing capability across the process as a whole and in particular key areas.

Chapter 15: Concept Check Questions

- Which of the following would NOT be a good measure of innovation performance?

- Which of the following is often associated with innovation success? (Several choices may be correct.)

- Which of the following would you NOT expect to hear people saying in an innovative organization?

- Which of these statements might you expect people to make in an innovative organization? (Several choices may be correct.)

- Which of the following would you expect to hear in a successful innovating company? (Several choices may be correct.)

- Which of the following would you NOT expect to hear in an innovative organization?

- Which of the following would you NOT expect to hear people saying about an innovative organization?

Further Reading

A wide range of books and online reviews of innovation now offer some form of audit framework including the Pentathlon model from Cranfield University [48] and Bettina von Stamm’s “Innovation wave” model – see [49–52] for other examples. Commercial organizations such as IMP3rove (www.improve-innovation.eu) offer a benchmarking and review framework, and the International Standards Organization is now exploring establishing an international framework.

Websites include www.innovationforgrowth.co.uk, http://www.bobcooper.ca, http://innovationexcellence.com/, http://www.cambridgeaudits.com/. AIM Practice also has a variety of audit tools around innovation, and NESTA (https://www.nesta.org.uk/) has a number of reports linked to its major Innovation Index project.

Case Studies

You can find a number of additional downloadable case studies on the companion website, including the following:

References

- 1. Teece, D., G. Pisano, and A. Shuen, Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 1997. 18(7): 509–533.

- 2. Utterback, J., Mastering the dynamics of innovation. 1994, Boston, MA.: Harvard Business School Press. p. 256.

- 3. Christensen, C. and M. Raynor, The innovator’s solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth. 2003, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- 4. Bessant, J., Managing advanced manufacturing technology: The challenge of the fifth wave. 1991, Oxford/Manchester: NCC-Blackwell.

- 5. Nonaka, I., The knowledge creating company. Harvard Business Review, 1991. November–December: pp. 96–104.

- 6. Nelson, R. and S. Winter, An evolutionary theory of economic change. 1982, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- 7. Bessant, J. and S. Caffyn, Learning to manage innovation. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 1996. 8(1): 59–70.

- 8. Kolb, D. and R. Fry, “Towards a theory of applied experiential learning,” in Theories of group processes, C. Cooper, Editor. 1975, John Wiley: Chichester.

- 9. Senge, P., The fifth discipline. 1990, New York: Doubleday.

- 10. Argyris, C. and D. Schon, Organizational learning. 1970, Reading, Mass.: Addison Wesley.

- 11. Bessant, J. and J. Buckingham, Organisational learning for effective use of CAPM. British Journal of Management, 1993. 4(4): 219–234.

- 12. Weick, K., The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1993. 38: 628–652.

- 13. Welch, J., Jack! What I’ve learned from leading a great company and great people. 2001, New York: Headline.

- 14. Kim, L., Crisis construction and organizational learning: Capability building in catching-up at Hyundai Motor. Organization Science, 1998. 9: 506–521.

- 15. Leonard, D., Core capabilities and core rigidities: a paradox in new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 1992. 13: 111–125.

- 16. Cooper, R., Winning at new products (3rd edition). 2001, London: Kogan Page.

- 17. Monden, Y., The Toyota Production System. 1983, Cambridge, Mass.: Productivity Press.

- 18. Morris, L., M. Ma, and P. Wu, Agile Innovation: The revolutionary approach to accelerate success, inspire engagement, and ignite creativity. 2014, New York: Wiley.

- 19. Ries, E., The lean startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. 2011, New York: Crown.

- 20. Blank, S., Why the lean start-up changes everything. Harvard Business Review, 2013. 91(5): 63–72.

- 21. Rush, H., T. Brady, and M. Hobday, Learning between projects in complex systems. 1997, Centre for the study of Complex Systems.

- 22. Swan, J., “Knowledge, networking and innovation: Developing an understanding of process,” in International Handbook of Innovation, L. Shavinina, Editor. 2003, Elsevier: New York.

- 23. Nonaka, I., S. Keigo, and M. Ahmed, “Continuous innovation: The power of tacit knowledge,” in International Handbook of Innovation, L. Shavinina, Editor. 2003, Elsevier: New York.

- 24. Bessant, J. and D. Francis, Developing strategic continuous improvement capability. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 1999. 19(11).

- 25. Stapenhurst, T., The benchmarking book: Best practice for quality managers and practitioners. 2012, New York: Routledge.

- 26. Rush, H., et al., Benchmarking R&D institutes. R&D Management, 1995. 25(1): 89–100.

- 27. Camp, R., Benchmarking – The search for industry best practices that lead to superior performance. 1989, Milwaukee, WI.: Quality Press.

- 28. Dimanescu, D. and K. Dwenger, World-class new product development: Benchmarking best practices of agile manufacturers. 1996, New York: Amacom.

- 29. Zairi, M., Effective benchmarking: Learning from the best. 1996, London: Chapman and Hall.

- 30. Morris, M., J. Bessant, and J. Barnes, Using learning networks to enable industrial development: Case studies from South Africa. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 2006. 26(5): 557–568.

- 31. Kaplinsky, R., F. den Hertog, and B. Coriat, Europe’s next step. 1995, London: Frank Cass.

- 32. Paulk, M., et al., Capability maturity model for software. 1993, Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie-Mellon University.

- 33. Garvin, D., How the Baldrige award really works. Harvard Business Review, 1991(November/December): 80–93.

- 34. Chiesa, V., P. Coughlan, and C. Voss, Development of a technical innovation audit. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 1996. 13(2): 105–136.

- 35. Voss, C.e.a., Made in Europe 3; the small company study. 1999, London Business School/ IBM Consulting: London.

- 36. Design_Council, Living innovation. 2002, Design Council/ Department of Trade and Industry website: http://www.livinginnovation.org.uk: London.

- 37. Francis, D., Developing innovative capability. 2001, University of Brighton: Brighton.

- 38. NESTA, The innovation index. 2009, NESTA: London.

- 39. Amabile, T., How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, 1998. September/October: 77–87.

- 40. Ekvall, G., “The organizational culture of idea management,” in Managing Innovation, J. Henry and D. Walker, Editors. 1991, Sage: London.

- 41. Bessant, J., High involvement innovation. 2003, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- 42. Adams, R., Innovation management measurement: A review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2006. 8: 21–47.

- 43. Tidd, J., ed. From knowledge management to strategic competence: Measuring technological, market and organizational innovation. 2000, Imperial College Press: London.

- 44. Luchs, B., Quality as a strategic weapon. European Business Journal, 1990. 2(4): 34–47.

- 45. Kay, J., Foundations of corporate success: How business strategies add value. 1993, Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 416.

- 46. NESTA, Hidden innovation. 2007, NESTA: London.

- 47. Stoneman, P., Soft innovation. 2010, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 48. Goffin, K. and R. Mitchell, Innovation management. 2005, London: Pearson.

- 49. Dodgson, M., A. Salter, and D. Gann, The management of technological innovation. Second ed. 2008, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 50. Trott, P., Innovation management and new product development. 2nd ed. 2004, London: Prentice-Hall.

- 51. Von Stamm, B., The innovation wave. 2003, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- 52. Von Stamm, B., Managing innovation, design and creativity. 2nd ed. 2008, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.