CHAPTER 6

Search Strategies for Innovation

It’s clear that opportunities for innovation are not in short supply – and they arise from many different directions. The key challenge for innovation management is how to make sense of the potential input – and to do so with often limited resources. No organization can hope to cover all the bases, so there needs to be some underlying strategy to how the search process is undertaken. In this chapter, we’ll try and develop a simple framework based around five key questions to help contend with the search challenge.

One way to manage this challenge is to impose some dimensions on the search space to help us frame where and why we might search for innovation triggers. These might include the following:

- What? – the different kinds of opportunities being sought in terms of incremental or radical change

- When? – the different search needs at different stages of the innovation process

- Who? – the different players involved in the search process, and in particular, the growing engagement of more people inside and outside the organization

- Where? – from local search aiming to exploit existing knowledge through to radical and beyond into new frames

- How? – mechanisms for enabling search

Figure 6.1 illustrates this framework.

FIGURE 6.1 The five-question framework.

6.1 The Innovation Opportunity

Identifying a need that no one has worked on before or finding novel ways to meet an existing need lies behind many new business ideas. For example, Jeff Bezos picked up on the needs (and frustrations) around conventional retail and has built the Amazon empire on the back of using new technologies to meet these in a different way. Air BnB (“I need to find somewhere to stay”), NextBike, Zipcar (“I need easy short-term access to transport”) and WhatsApp (“I need to communicate with my friends”) are other well-known examples.

A good source of opportunity for entrepreneurs is to look at the underlying need that people have for goods and services – and then to ask if there are different ways of expressing or meeting this need. For example, the huge industry around selling drills and screws and other devices to the domestic market is not about a desire for owning power tools but reflects a more basic need – how can I put a picture or photograph on the wall? Innovation opportunity introduces other potential ways of meeting this need.

Push or Pull Innovation?

One important question about innovation opportunity is the relative importance of the push or pull forces outlined in the previous chapter. This has been the subject of many innovation studies over the years, using a variety of different methods to try and establish which is more important (and therefore where organizations might best place their resources). The reality is that innovation is never a simple matter of push or pull but rather their interaction; as Chris Freeman, one of the pioneers of innovation research [1], said: “necessity may be the mother of invention but procreation needs a partner!” Innovations tend to resolve into vectors – combinations of the two core principles. And these direct our attention in two complementary directions – creating possibilities (or at least keeping track of what others are doing along the R&D frontier) and identifying and working with needs. Importantly, the role of needs in innovation is often to translate or select from the range of knowledge push possibilities, the variant of which becomes the dominant strain. Out of all the possible bicycle ideas that were around in the mid-nineteenth century – some with three wheels, some with no brakes, some with big and small wheels, some with direct drives, and some without even a saddle – we eventually got to the dominant design that is with us today [2]. Similarly, the iPod wasn’t the first MP3 player, but it somehow clicked as the one that resonated best with user needs.

In fact, most of the sources of innovation we mentioned earlier involve both push and pull components – for example, “applied R&D” involves directing the push search in areas of particular need. Regulation both pushes in key directions and pulls innovations through in response to changed conditions. User-led innovation may be triggered by user needs, but it often involves them creating new solutions to old problems – essentially pushing the frontier of possibility in new directions.

There is a risk in focusing on either of the “pure” forms of push or pull sources. If we put all our eggs in one basket, we risk being excellent at invention but without turning our ideas into successful innovations – a fate shared by too many would-be entrepreneurs. But equally too close an ear to the market may limit us in our search – as Henry Ford is reputed to have said, “if I had asked the market they would have said they wanted faster horses!” The limits of even the best market research lie in the fact that they represent sophisticated ways of asking people’s reactions to something that is already there – rather than allowing for something completely outside their experience so far.

Incremental or Radical Innovation?

Another key dimension is around incremental or radical innovation. As we saw in Chapter 1, innovation can happen along a spectrum running from incremental (“do what we do, but better”) through to radical (“do something completely different”). And we’ve also seen that there is a pattern of what could be termed “punctuated equilibrium” with innovation – most of the time, innovation is about exploiting and elaborating, creating variations on a theme within an established technical, market, or regulatory trajectory. But occasionally, there is a breakthrough, which creates a new trajectory – and the cycle repeats itself. This suggests that much of our attention in searching for innovation triggers will be around incremental improvement innovation – the different versions of a piece of software, the Mk 2, 3, 4 of a product or the continuing improvement of a business process to make it closer to lean. But we will need to have some element of our portfolio focused on the longer-range, higher risk, which might lead to the breakthrough and set up a new trajectory.

For all but the smallest start-up, we will be looking to balance a portfolio of ideas – most of them “do better” incremental improvements on what has gone before but with a few that are more radical and may even be “new to the world.” The big advantage of innovation of this kind is that there is a degree of familiarity, the risk is lower, and we are moving forward along a path that has already been trodden. The benefits from doing so may be small in themselves, but their effect is cumulative. And the ways in which we can search for such opportunities – tools and directions – are essentially well established and systematic.

By contrast, taking a leap forward could bring big gains – but also carries higher risk. Since we are moving into unknown territory, there will be a need to experiment – and a good chance that much of that experimentation will fail. We won’t be clear about the directions in which we want to go, and so there is a real risk of going up blind alleys or getting trapped in one-way streets. Essentially, the kind of searching we do – and the tools we use – will be different.

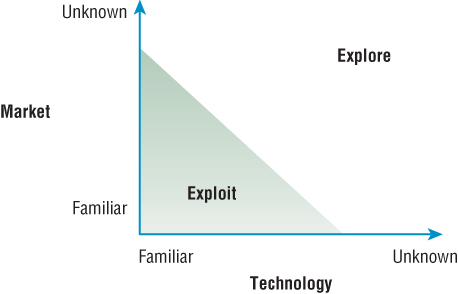

Exploit or Explore?

A core theme in discussion of innovation relates to the tensions in search behavior between “exploit” and “explore” activities [3]. On the one hand, firms need to deploy knowledge resources and other assets to secure returns, and a “safe” way of doing so is to harvest a steady flow of benefits derived from “doing what we do better.” This has been termed “exploitation” by innovation researchers, and it essentially involves “the use and development of things already known” [4]. It builds strongly through “knowledge leveraging activities” [5] on what is already well established – but in the process leads to a high degree of path dependency – “firms accumulated exploitation experience reinforces established routines within domains” [4].

The trouble is that in an uncertain environment, the potential to secure and defend a competitive position depends on “doing something different,” that is, radical product or process innovation rather than imitations and variants of what others are also offering [6]. This kind of search had been termed “exploration” and is the kind that involves “long jumps or reorientations that enable a firm to adopt new attributes and attain new knowledge outside its domain” [7,8].

The aforementioned tension comes because the organizational routines needed to support these activities differ. Incremental exploitation innovation is about highly structured processes and often high-frequency, small-scale innovation carried out within operating units. Radical innovation, by contrast, is occasional and high-risk, often requiring a specific and cross-functional combination of resources and a looser approach to organization and management [9].

There is no easy prescription for doing these two activities, but most organizations manage a degree of “ambidexterity” through the use of a combination of approaches across a portfolio [10,11]. So, for example, technological search activity is managed by investment in a range of R&D projects with a few “blue sky”/high risk outside bets and a concentration of projects around core technological trajectories [12]. Market research is similarly structured to develop deep and responsive understanding of key market segments but also allowing some search around peripheral and emergent constituencies [13,14].

Figure 6.2 illustrates this concept.

FIGURE 6.2 Exploit and explore options in search.

6.2 When to Search

Another influence on our choice of search approach is around timing – at different stages in the product or industry life cycle, the emphasis may be more or less on push or pull. For example, mature industries will tend to focus on pull, responding to different market needs and differentiating by incremental innovation in key directions of user need. By contrast, a new industry – for example, the emergent industries based on genetics or nanomaterial technology – is often about solutions looking for a problem. So we would expect a different balance of resources committed to push or pull within these different stages.

This kind of thinking is reflected in the Abernathy/Utterback model of innovation life cycle, which we covered in Chapter 1 [15]. This sees innovation at the early fluid stage being characterized by extensive experimentation and with emphasis on product – creating a radical new offering. As the dominant design emerges, attention shifts toward more incremental variation around the core trajectory – and as the industry matures, so emphasis shifts to process innovation aimed at improving parameters such as cost and quality. Once again this helps allocate scarce search resources in particular ways.

Another important influence on the timing question is around diffusion – the adoption and elaboration of innovation over time. Innovation adoption is not a binary process but rather one that takes place gradually over time, following some version of an S-curve [16]. At the early stages, innovative users with high tolerance for failure will explore, to be followed by early adopters. This gives way to the majority following their lead until finally the remnant of a potential adopting population – the laggards in Roger’s terms – adopt or remain stubbornly resistant. Understanding diffusion processes and the influential factors (which we will explore in more detail in Chapter 9) is important because it helps us understand where and when different kinds of triggers are picked up. Lead users and early adopters are likely to be important sources of ideas and variations, which can help shape an innovation in its early life, whereas the early and late majority will be more a source of incremental improvement ideas [17].

6.3 Who Is Involved in Search

Innovation is about translating knowledge into value – and the search stage is very much about how to obtain the knowledge that fuels the process. Central to this is seeing knowledge as a social process with people acting in different ways as carriers and communicators. It’s a living thing, carried by people, and innovation works when they talk to each other, share, combine, extend, and so on. Innovation research offers us some powerful principles to help understand this – for example:

- Knowledge networks Ask most people about “social networking” and they’ll assume that it is something that grew up in the twenty-first century. But it has much older roots; back in the 1890s, sociologists such as Emile Durkheim and Georg Simmel were already exploring how and why networks and clusters form [18]. And in the 1930s, Jacob Moreno laboriously mapped (using pencil and paper) the interactions between people in, laying the foundations for today’s social network analysis toolkit, and developing the source algorithms behind Facebook and Twitter [19].

Social networks around knowledge aren’t all the same – back in the 1970s Mark Granovetter showed that they varied in terms of their connectivity [20]. Much of the time they involve dense connections or people sharing similar and complementary information – something he called “strong ties.” But for new knowledge to move between networks we need much looser links between different worlds – what he called “weak ties.”

- Knowledge connectors Making knowledge connections isn’t simply joining the dots in mechanical fashion. Researchers have shown that we need to look at the role of brokers, people who straddle the boundaries of different knowledge worlds and enable traffic to flow across them. These days we talk knowingly about social capital and the importance of building up networks – “its not what you know, but who you know” – but this idea owes much to sociologist Ronald Burt and his research in the 1990s [21].

The core of his theory is that where two “knowledge worlds” possess different, “nonredundant” information (they know something you don’t) then there is a “structural hole” between them. Brokers provide the bridge between these and are central to effective flow of knowledge across them. These days some of the new knowledge technologies can provide ways of amplifying and even automating some aspects of this. (Think about Facebook’s ability to find “friends” you might like to connect with – and about the potential application of “knowledge friending” in terms of moving knowledge around organizations and building relevant networks.)

- Knowledge flow It’s also important to remember that knowledge flows through people and their behavior matters. Tom Allen’s pioneering work in the 1970s gave us some powerful insights into the ways this happens – for example, through technological gatekeepers who are able to see the relevance of external knowledge but who also have the internal social connections to enable the right person to connect to it [22]. Procter and Gamble’s “Connect and develop” strategy includes the key role of “technology entrepreneurs,” and they are credited with some breakthrough open-innovation successes such as printed Pringles chips or the Mr Clean Magic Eraser.

It’s also about physical connections between people; the famous “Allen curve” shows that there is a strong negative correlation between physical distance and frequency of communication between people. Not for nothing did Steve Jobs reorganize the layout at Pixar, so it was impossible for people not to bump into each other and spark conversations. BMW uses the same principles in the underlying architecture of its futuristic R&D Centre in Munich [23].

- Knowledge concentration Just as in the brain certain groups of neurons are associated with particular areas of specialization, so in organizations, we are learning the importance of communities of practice. A concept originally developed by Etienne Wenger and Jean Lave, these are groups of people with common interests who collect and share experience (often tacit in nature) about dealing with their shared problem in a variety of different contexts [24]. They represent deep pools of potentially valuable knowledge – for example, John Seeley Brown and Paul Duguid report on Xerox’s experience in the world of office copiers [25]. Its technical sales representatives worked as a community of practice, exchanging tips and tricks over informal meetings. Eventually, Xerox created the “Eureka” project to allow these interactions to be shared across their global network; it represents a knowledge store that has saved the corporation well over $100 million.

- Knowledge architecture There’s a downside to concentrating knowledge in a community or network. For as long as changes take place within the context of this architecture, things work well, and shifts in one or more components can be handled effectively. But when the whole knowledge game changes – for example, when an industry such as automobile, suddenly shifts into a new world of machine learning, intelligent sensors, and driverless operation – then the networks need to change. As Rebecca Henderson and Kim Clark showed, established organizations often find difficulties in such shifts; they need to balance the advantages of working with dominant architectures – formal groups, close ties, concentration, with the need to preserve the capacity for new architectures [26].

- Other dimensions These include knowledge transformation (how to mobilize and work with tacit knowledge), knowledge articulation (how to get at the knowledge held by employees about the jobs they do – what Joseph Juran famously called “the gold in the mine”), and knowledge assimilation (how to move new knowledge from outside to a point of active deployment) [27].

6.4 Where to Search – The Innovation Treasure Hunt

As we saw earlier, there is a long-standing discussion in innovation literature around “exploration” and “exploitation.” Both are search behaviors, but one is essentially incremental, doing what we do better, adaptive learning; the second is radical, do different, generative learning [5,28]. A key issue is how organizations can operationalize these different behaviors – what “routines” (structures, processes, behaviors) can they embed to enable effective exploration and exploitation? While literature is fairly clear about routines for exploitation – essentially innovation approaches to enable continuous incremental extension and adaptation – there is less about exploration.1

Striking a suitable balance is tricky enough under what might be called “steady-state” innovation conditions, but the work of Christensen and others on disruptive innovation suggests that under certain conditions (e.g., the emergence of completely new markets) established incumbents get into difficulties. They are too focused in their search routines (both explore and exploit) for dealing with what they perceive as a relevant part of the environment (their market “value network”), and they fail to respond to a new emerging challenge until it is often too late. This is partly because their search behavior is so routinized, embedded in reward structures and other reinforcement mechanisms, that it blinds the organization to other signals [29–31].

Importantly, this is not a failure in innovation management per se – the firms described are in fact very successful innovators under the “steady-state” conditions of their traditional marketplace, deploying textbook routines and developing close and productive networks with customers and suppliers. The problem arises at the edge of their “normal” search space and under the discontinuous conditions of new market emergence.

In a similar fashion, incumbent organizations often suffer when technologies shift in discontinuous fashion. Again their established repertoire of search routines tends toward exploitation and bounds their search space – with the risk that developments outside can achieve considerable momentum, and by the time they are visible, the organization has little reaction time [15]. This is further complicated by the issue of sunk costs, which commit the incumbent to the earlier generation of technology, and the “sailing ship” effect whereby their exploit routines continue to bring a stream of improvements to the old technology and sustain that pathway while the new technology matures [32]. (The “sailing ship” effect refers to the fact that when steamships were first invented, it gave a spur to an intensive sequence of innovation in sailing ship technology, which meant the two could compete for an extended period before the underlying superiority of steamship technology worked through.)

Ambidexterity in Search

It is also clear that another key issue is how to integrate these different approaches within the same organization – how (or even if it is possible) to develop what Tushman calls “ambidextrous” capability around innovation management [33]. Much recent literature on disruptive, radical, discontinuous innovation highlights the tensions that are set up and the fundamental conflicts between certain sets of routines – for example, Christensen’s theory suggests that by being too good at “exploit” routines to listen to and work with the market, incumbent firms fail to pick up or respond to other signals from new fringe markets until it is too late.

A key problem in searching for innovation opportunities is not just that such firms fail to get the balance right between exploit and explore but also because there are choices to be made about the overall direction of search. Characteristic of many of these businesses is that they continue to commit to “explore” search behavior – but in directions that reinforce the boundaries between them and emergent new innovation space. For example, in many of the industries Christensen studied, high rates of R&D investment pushed technological frontiers even further – resulting in many cases in “technology overshoot.” This is not a lack of search activity but rather a problem of direction.

The issue is that the search space is not one-dimensional. As Henderson and Clark point out that it is not just a question of searching near or far from core knowledge concepts but also across configurations – the “component/architecture challenge.” They argue that innovation rarely involves dealing with a single technology or market but rather a bundle of knowledge that is brought together into a configuration. Successful innovation management requires that we can get hold of and use knowledge about components but also about how those can be put together – what they termed the architecture of an innovation [26].

Framing Innovation Search Space

One way of looking at the search problem is in terms of the ways in which “innovation space” is framed by the organization. Just as human beings need to develop cognitive schemas to simplify the “blooming, buzzing confusion” that the myriad stimuli in their environment offer them, so organizations make use of simplifying frames. They “look” at the environment and take note of elements that they consider relevant – threats to watch out for, opportunities to take advantage of, competitors and collaborators, and so on. The construction of such frames helps give the organization some stability and – among other things – defines the space within which it will search for innovation possibility. While there is scope for organizations to develop their own individual ways of seeing the world – their business models – in practice, there is often commonality within a sector. So most firms in a particular field will adopt similar ways of framing – assuming certain “rules of the game,” following certain trajectories in common.

These frames correspond to accepted “architectures” – the ways in which players see the configuration within which they innovate. The dominant architecture emerges over time but once established becomes the “box” within which further innovation takes place. We are reminded of the difficulties in thinking and working outside this box because it is reinforced by the structures, processes, and toolkit – the core routines – which the organization (and its key reference points in a wider network of competitors, customers, and suppliers) has learned and embedded.

In practice, these models often converge around a core theme – although organizations might differ, they often share common models about how their world behaves. So most firms in a particular sector will adopt similar ways of framing – assuming certain “rules of the game,” following certain trajectories in common. And this shapes where and how they tend to search for opportunities – it emerges over time but once established becomes the “box” within which further innovation takes place.

It’s difficult to think and work outside this box because it is reinforced by the structures, processes, and tools that the organization uses in its day-to-day work. The problem is also that such ways of working are linked to a complex web of other players in the organization’s “value network” – its key competitors, customers, and suppliers – who reinforce further the dominant way of seeing the world.

Case Study 6.1 gives an example.

This perspective highlights the challenge of moving between knowledge sets. Firms can be radical innovators but still be “upstaged” by developments outside their search trajectory. The problem is that search behavior is essentially bounded exploration and raises a number of challenges:

- When there is a shift to a new mind-set – cognitive frame – established players may have problems because of the reorganization of their thinking that is required. It is not simply adding new information but changing the structure of the frame through which they see and interpret that information. They need to “think outside the box” within which their bounded exploration takes place – and this is difficult because it is highly structured and reinforced [34].

- This is not simply a change of personal or even group mind-set – the consequence of following a particular mind-set is that artifacts and routines come into place, which block further change and reinforce the status quo. Christensen points out, for example, the difficulty of seeing and accepting the relevance of different signals about emerging markets because the reward systems around sales and marketing are biased toward reinforcing the established market. Henderson and Clark highlight the problems of social and knowledge networks that need to be abandoned and new ones set up in the move to new architectures in photolithography equipment. Day and Shoemaker show how organizations develop particular ways of seeing and not seeing [35]. These are all part of the bounding process – essentially, they create the “box” we feel we need to get out of.

- Architectural – as opposed to component innovation – requires letting go of existing networks and building new ones [36]. This is easier for new players to do and hard for established players because the inertial tendency is to revert to established pathways for knowledge and other exchange – the finding, forming, and performing problem [36].

- The new frame may not necessarily involve radical change in technology or markets but rather a rearrangement of the existing elements. Low-cost airlines did not, for example, involve major technological shifts in aircraft or airport technology but rather problem-solving to make flying available to an underserved market segment [37]. Similarly, the “bottom of the pyramid” development is not about radical new technologies but about applying existing concepts to underserved markets with different characteristics and challenges [38]. There may be incremental innovation – problem-solving – to make the new configuration work. This is not usually new to the world but rather problem-solving.

6.5 A Map of Innovation Search Space

In summarizing the different sources of innovation and how we might organize and manage the process of searching for them, we can use a simple map – see Figure 6.3. The vertical axis refers to the familiar “incremental/radical” dimension in innovation, while the second relates to environmental complexity – the number of elements and their potential interactions. Rising complexity means that it becomes increasingly difficult to predict a particular state because of the increasing number of potential configurations of these elements. In this way, we capture the “component/architecture” challenge outlined earlier.

FIGURE 6.3 A map of innovation search space.

Firms can innovate at component level – the left-hand side – in both incremental and radical fashion, but such changes take place within an assumed core configuration of technological and market elements – the dominant architecture. Moving to the right introduces the problem of new and emergent architectures arising out of alternative ways of framing among complex elements.

Organizations simplify their perceptions of complex environments, choosing to pay attention to certain key features that they interpret via a shared mental model. They learn to manage innovation within this space and construct routines – embedding structures and processes and building networks to support and enable work within it. In mature sectors, a characteristic is the dominance of a particular logic that gives rise to business models of high similarity – for example, industries such as pharmaceuticals or integrated circuit design and manufacture are characterized by a small number of actors playing to a similar set or rules involving R&D spend, sales, and marketing, and so on.

But while such models represent a “dominant logic” or trajectory for a sector, they are not the only possible way of framing things [39]. In high-complexity environments with multiple sources of variety, it becomes possible to configure alternative models – to “reframe” the game and arrive at an alternative architecture. While many attempts at reframing may fail, from time to time, alternatives do emerge, which better deal with the environmental complexity and become the new dominant model.

Using this idea of different “frames,” we can explore four zones shown in Figure 6.3, which have different implications for the ways in which innovation is managed. While those approaches for dealing with the left-hand side – zones 1 and 2 – are well developed, we argue that there is still much to learn about the right-hand side challenges and how to approach them in practical terms – via methods and tools.

Zone 1

Zone 1 corresponds to the “exploit” field discussed earlier and assumes a stable and shared frame within which adaptive and incremental development takes place. Search routines here are associated with refining tools and methods for technological and market research, deepening relationships with established key players. Examples would be working with key suppliers, getting closer to customers, and building key strategic alliances to help deliver established innovations more efficiently.

The structures for carrying out this kind of search behavior are clearly defined with relevant actors – department or functions responsible for market research, product (service) development, and so on. They involve strong ties in external networks with customers, suppliers, and other relevant actors in their wider environment. The work of core groups such as R&D is augmented by high levels of participation across the organization – because the search questions are clearly defined and widely understood, high involvement of nonspecialists is possible. So procurement and purchasing can provide a valuable channel as can sales and marketing – since these involve contact with external players [40]. Process innovation can be enabled by inviting suggestions for incremental improvement across the organization – a high-involvement kaizen model [41].

Zone 2

Zone 2 involves search into new territory, pushing the frontiers of what is known, and deploying different search techniques for doing so. But this still takes place within an established framework – a shared mental model, which we could term “business model as usual.” R&D investments here are on big bets with high strategic potential, patenting, and intellectual property (IP) strategies aimed at marking out and defending territory, riding key technological trajectories (such as Moore’s Law in semiconductors). Market research similarly aims to get close to customers but to push the frontiers via empathic design, latent needs analysis, and so on. Although the activity is risky and exploratory, it is still governed strongly by the frame for the sector – as Pavitt observed, there are certain sectoral patterns that shape the behavior of all the players in terms of their innovation strategies [42].

The structures involved in such exploration are, of necessity, highly specialized.

Formal R&D and within that sophisticated specialization is the pattern on the science/technology frontier, often involving separate facilities. Here too there is mobilization of a network of external but similarly specialized researchers – in university, public, and commercial laboratories – and the formation of specific strategic alliances and joint ventures around a particular area of deep technology exploration. The highly specialized nature of the work makes it difficult for others in the organization to participate. Indeed, this gap between worlds can often lead to tensions between the “operating” and the “exploring” units, and the boardroom battles between these two camps for resources are often tense. In a similar fashion, market research is highly specialized and may include external professional agencies in its network with the task of providing sophisticated business intelligence around a focused frontier.

Zone 3

Zones 1 and 2 represent familiar territory in discussion of exploit/explore in innovation search. But arguably, they take place within an accepted frame, a way of seeing the world that essentially filters and shapes perceptions of what is relevant and important. This corresponds to Henderson and Clark’s architecture and, as we have argued, defines the “box” within which innovative activity is expected to occur. Such framing is, however, a construct and open to alternatives – and Zone 3 is essentially associated with reframing. It involves searching a space where alternative architectures are generated, exploring different permutations and combinations of elements in the environment. Importantly, this often happens by working with elements in the environment not embraced by established business models – for example, Christensen’s work on fringe markets, Prahalad’s bottom of the pyramid, or von Hippel’s extreme users [38,43,44].

As an illustration, the low-cost airline industry was not a development of new product or process – it still involves airports, aircraft, and so on. Instead, the innovation was in position and paradigm, reframing the business model by identifying new elements in the markets – students, pensioners, and so on – who did not yet fly but might if the costs could be brought down. Rethinking the business model required extensive product and process innovation to realize it – for example, in online booking, fast turnaround times at airports, multiskilling of staff, and so on – but the end result was reframing and creation of new innovation space.

Zone 4

Zone 4 represents the “edge of chaos” complex environment where innovation emerges as a product of a process of coevolution. This is not the product of a predefined trajectory so much as the result of complex interactions between many independent elements [45,46]. Processes of amplification and feedback reinforce what begin as small shifts in direction and gradually define a trajectory. This is the pattern – the “fluid state” – before a dominant design emerges and sets the standard [15]. As a result, it is characterized by very high levels of experimentation.

Search strategies here are difficult since it is impossible to predict what is going to be important or where the initial emergence will start and around which feedback and amplification will happen. The best an organization can do is to try and place itself within that part of its environment where something might emerge and then develop fast reactions to weak signals. “Strategy” here can be distilled down to three elements – be in there, be in there early, and be in there actively (i.e., in a position to be part of the feedback and amplification mechanisms).

With these four zones, we have a simple map on which to explore innovation routines. Our concern in this chapter is with search routines – how do organizations manage the process of recognizing and acquiring key new knowledge to enable the innovation process? There are also implications for how they assimilate and transform (select) and how they exploit and implement, but we will not focus on those at this stage. As we have suggested, each zone represents a different kind of challenge and leads to the use of different methods and tools. And while the toolbox is well stocked for zones 1 and 2, there is value in experimentation and experience sharing around zones 3 and 4.

Table 6.1 summarizes the challenge.

TABLE 6.1 Challenges in Innovation Search

| Zone | Search Challenges | Tools and Methods | Enabling Structures |

| 1. “Business as usual” – innovation but under “steady-state” conditions, little disturbance around core business model |

Exploit – incrementally extends boundaries of technology and market Refines and improves Close links/strong ties with key players |

“Good practice” new product/service development Close to customer Technology platforms and systematic exploitation tools |

Formal and mainstream structures High involvement across organization Established roles and functions (including production, purchasing, etc.) |

| 2. “Business model as usual” – bounded exploration within this frame |

Exploration – pushing frontiers of technology and market via advanced techniques Close links with key strategic knowledge sources |

Advanced tools in R&D, market research Increasing “open-innovation” approaches to amplify strategic knowledge search resources |

Formal investment in specialized search functions – R&D, Market Research, and so on |

|

3. Alternative frame – taking in new/different elements in environment Variety matching, alternative architectures |

Reframe – exploration of alternative options, introduction of new elements Experimentation and open-ended search Breadth and periphery important |

Alternative futures Weak signal detection User-led innovation Extreme and fringe users Prototyping – probe and learn Creativity techniques Bootlegging, and so on |

Peripheral/ad hoc Challenging – “licensed fools” Corporate venture units Internal entrepreneurs, Scouts Futures groups Brokers, boundary spanning and consulting agencies |

|

4. Radical – new to the world – possibilities New architecture around as yet unknown and established elements |

Emergence – need to coevolve with stakeholders

|

Complexity theory – feedback and amplification, probe and learn, prototyping, and use of boundary objects |

Far from mainstream “Licensed dreamers” Outside agents and facilitators |

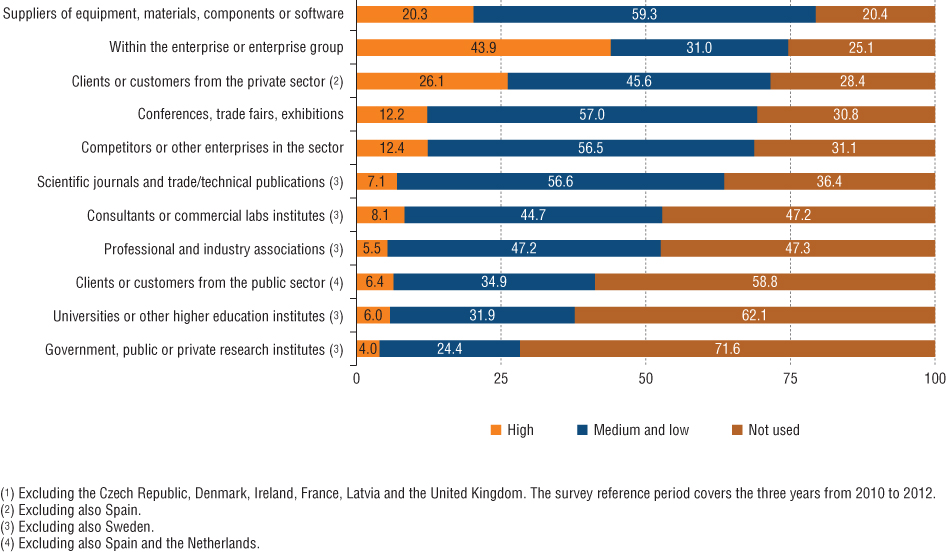

6.6 How to Search

Of course, the challenge in managing innovation is not one of classifying different sources but rather how to seek out and find the relevant triggers early and well enough to do something about them. In developing search strategies, we can make use of some of the broad dimensions highlighted earlier – for example, by ensuring that we have a balance between push and pull and between incremental and radical. A good place to start understanding broad strategies is to look at what firms actually do in searching for innovation triggers. There are many large-scale innovation surveys that ask around this theme – for example, the European Community Innovation Survey, which looks at the innovative behavior of firms across all the EU states as described in Figure 6.4.

FIGURE 6.4 Sources of information used for product and/or process innovations by degree of importance, EU-28, 2010–12 (1) (% of all product and or process innovative enterprises).

Source: Eurostat (online data code: inn_cis8_sou).

Similar data from the UK national Innovation Survey shows the breakdown by firm size (see Table 6.2).

TABLE 6.2 Breakdown of Sources of Innovation by Firm Size (Based on the UK National Innovation Survey)

Source: First findings from the UK Innovation Survey, 2011, Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, London.

| Per Cent | |||

|

10–250 Employees |

250+ Employees |

All (10+ Employees) |

|

|

Internal

Within your enterprise group |

39 | 52 | 39 |

|

Market

Suppliers of equipment Clients or customers Competitors or other enterprises in your industry Consultants, commercial labs, or private R&D institutes |

18 39 14 4 |

23 50 18 7 |

19 39 15 4 |

|

Institutional

Universities or other higher education institutes |

3 | 2 | 3 |

| Government or public research institutes | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Other Sources | |||

| Technical, industry, or service standards | 8 | 15 | 8 |

| Conferences, trade fairs, exhibitions | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Scientific journals and trade/technical publications | 8 | 15 | 8 |

| Professional and industry associations | 6 | 8 | 6 |

Data from studies such as these gives us one picture – and it reinforces the view that successful innovation is about spreading the net as widely as possible, mobilizing multiple channels. Although surveys of this kind tell us a lot, they also miss important elements in the sources-of-innovation picture. A lot of incremental innovation and how it is triggered lies beneath the radar screen, and there is a bias toward product innovation where we know that a great deal of incremental process improvement goes on. And it doesn’t capture position or business model innovation so well, again especially at the incremental end. It tends to focus on the “obvious” search agents such as R&D or market research departments – though others may be involved, for example, purchasing – and within the business, the idea of suggestion schemes and high-involvement innovation [47]. But it gives us a broad picture – and underlines the need for an extensive net.

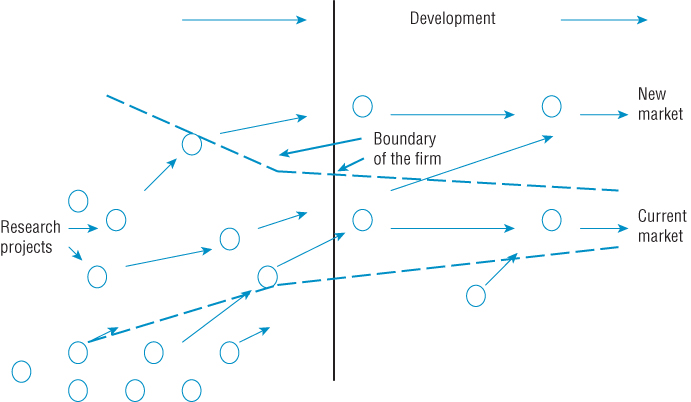

Building rich and extensive linkages with potential sources of innovation has always been important – for example, studies by Carter and Williams in the United Kingdom in the 1950s identified one key differentiator between successful and less successful innovating firms as the degree to which they were “cosmopolitan” as opposed to “parochial” in their approach toward sources of innovation [48]. There are, of course, arguments for keeping a relatively closed approach – for example, there is a value in doing your own R&D and market research because the information collected is then available to be exploited in ways that the business can control. It can choose to push certain lines, hold back on others, keep things essentially within a closed system. But as we’ve seen, the reality is that innovation is triggered in all sorts of ways, and a sensible strategy is to cast the new as widely as possible. In what is termed “open innovation,” organizations move to a more permeable view of knowledge in which they recognize the importance of external sources and also make their own knowledge more widely available [49]. Figure 6.5 illustrates the open-innovation model [49].

FIGURE 6.5 The open-innovation model [49].

Chesbrough, H. (2003) Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

This is not without its difficulties – on the one hand, it makes sense to recognize that in a knowledge-rich world, “not all the smart guys work for us.” Even large R&D spenders such as Procter and Gamble (annual R&D budget around $3 billion and about 7000 scientists and engineers working globally in R&D) are fundamentally rethinking their models – in their case, switching from “Research and Develop” to “Connect and Develop” as the dominant slogan, with the strategic aim of moving from closed innovation to sourcing 50% of their innovations from outside the business [50]. But on the other hand, we should recognize the tension that poses around intellectual property (how do we protect and hold on to knowledge when it is now much more mobile – and how do we access other people’s knowledge?), around appropriability (how do we ensure a return on our investment in creating knowledge?) and around the mechanisms to make sure that we can find and use relevant knowledge (when we are now effectively sourcing it from across the globe and in all sorts of unlikely locations?). In this context, innovation management’s emphasis shifts from knowledge creation to knowledge trading and managing knowledge flows [51].

We will return to this theme of “open innovation” and how to enable it, in the next chapter and in Chapter 11.

6.7 Absorptive Capacity

One more broad strategic point concerns the question of where, when, and how organizations make use of external knowledge to grow. It’s easy to make the assumption that because there is a rich environment full of potential sources of innovation, every organization will find and make use of these. The reality is, of course, that they differ widely in their ability to make use of such trigger signals – and the measure of this ability to find and use new knowledge has been termed “absorptive capacity” (AC).

The concept was first introduced by Cohen and Levinthal, who described it as “the ability of a firm to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends” and who saw it as “largely a function of the firm’s level of prior related knowledge” [52]. It is an important construct because it shifts our attention to how well firms are equipped to search out, select, and implement knowledge.

The underlying construct of AC is not new – discussion of firm learning forms the basis of a number of studies going back to the work of Arrow, March, Simon, and others [53,54]. In the area of innovation studies, the ideas behind “technological learning” – the processes whereby firms acquire and use new technological knowledge and the underlying organizational and managerial process that are involved – were extensively discussed by, inter alia, Freeman, Bell and Pavitt, and Lall [1,55,56]. Cohen and Levinthal’s original work was based on exploring (via mathematical modeling) the premise that firms might incur substantial long-run costs for learning a new “stock” of information and that R&D needed to be viewed as an investment in today and tomorrow’s technology. In later work, they broadened and refined the model and definition of AC to include more than just the R&D function and also explored the role of technological opportunity and appropriability in determining the firm’s incentive to build AC.

AC is clearly not evenly distributed across a population. For various reasons, firms may find difficulties in growing through acquiring and using new knowledge. Some may simply be unaware of the need to change, never mind having the capability to manage such change. Such firms – a classic problem of small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) growth, for example – differ from those that recognize in some strategic way the need to change, to acquire, and to use new knowledge but lack the capability to target their search or to assimilate and make effective use of new knowledge once identified. Others may be clear what they need but lack the capability in finding and acquiring it. And others may have well-developed routines for dealing with all of these issues and represent resources on which less experienced firms might draw – as is the case with some major supply chains focused around a core central player [57].

Reviewing the literature on why and when firms take in external knowledge suggests that this is not – as is sometimes assumed – a function of firm size or age. It appears instead that the process is more one of transitions via crisis – turning points [58]. Some firms do not make the transition, and others learn up to a limited level. Equally, the ability to move forward depends on the past – a point made forcibly by Cohen and Levinthal in their original studies.

Research Note 6.1 discusses this theme.

The key message from research on AC is that complex construct – acquiring and using new knowledge involves multiple and different activities around search, acquisition, assimilation, and implementation. Connectivity between these is important – the ability to search and acquire (potential AC in Zahra and George’s model) may not lead to innovation. To complete the process, further capabilities around assimilation and exploitation (realized AC) are also needed. Importantly, AC is associated with various kinds of search and subsequent activities, not just large firm formal R&D; mechanisms whereby SMEs explore and develop their process innovation, for example, are also relevant.

AC is essentially about accumulated learning and embedding of capabilities – search, acquire, assimilate, and so on – in the form of routines (structures, processes, policies, and procedures) that allow organizations to repeat the trick. Firms differ in their levels of AC, and this places emphasis on how they develop and establish and reinforce these routines – in other words, their ability to learn. Developing AC involves two complementary kinds of learning. Type 1 – adaptive learning – is about reinforcing and establishing relevant routines for dealing with a particular level of environmental complexity, and type 2 – generative learning – is for taking on new levels of complexity [61,62].

6.8 Tools and Mechanisms to Enable Search

Within this broad framework, firms deploy a range of approaches to organizing and managing the search process. For example, much experience has been gained in how R&D units can be structured to enable a balance between applied research (supporting the “exploit” type of search) and more wide-ranging, “blue sky” activities (which facilitate the “explore” side of the equation) [12]. These approaches have been refined further along “open-innovation” lines where the R&D work of others is brought into play and by ways of dealing with the increasingly global production of knowledge – for example, the pharmaceutical giant GSK deliberately pursues a policy of R&D competition across several major facilities distributed around the world. In a similar fashion, market research has evolved to produce a rich portfolio of tools for building a deep understanding of user needs – and which continues to develop new and further refined techniques – for example, empathic design, lead-user methods, and increasing use of ethnography.

Choice of techniques and structures depends on a variety of strategic factors such as those explored earlier – balancing their costs and risks against the quality and quantity of knowledge they bring in. Throughout the book, we have stressed the idea that managing innovation is a dynamic capability – something that needs to be updated and extended on a continuing basis to deal with the “moving frontier” problem. As markets, technologies, competitors, regulations, and all sorts of other elements in a complex environment shift, so we need to learn new tricks and sometimes let go of older ones that are no longer appropriate.

In the following section, we’ll look at some particular examples that are emerging in response to an “open innovation” context, which sees increasingly high levels of knowledge (market, legal, technical, etc.) and the need to tap into it more effectively.

Managing Internal Knowledge Connections

One area that has seen growing activity addresses a fundamental knowledge management issue that is well expressed in the statement “if only xxx (insert the name of any large organization) knew what it knows!” In other words, how can organizations tap into the rich knowledge (and potential innovation triggers) within its existing structures and amongst its workforce?

This has led to renewed efforts to deal with what is an old problem – for example, Procter and Gamble’s successes with “connect and develop” owe much to their mobilizing rich linkages between people who know things within their giant global operations and increasingly outside it. They use “communities of practice” [63] – Internet-enabled “clubs” where people with different knowledge sets can converge around core themes, and they deploy a small army of innovation “scouts” who are licensed to act as prospectors, brokers, and gatekeepers for knowledge to flow across the organization’s boundaries. (We discuss this in more detail in Chapter 7.) Intranet technology links around 10,000 people in an internal “ideas market” – and some of their significant successes have come from making better internal connections [50].

3M – another firm with a strong innovation pedigree dating back over a century – similarly put much of their success down to making and managing connections. Larry Wendling, Vice President for Corporate Research talks of 3M’s “secret weapon” – the rich formal and informal networking that links thousands of R&D and market-facing people across the organization. Their long-history of breakthrough innovations – from masking tape, through Scotchgard, Scotch tape, magnetic recording tape, to Post-Its and their myriad derivatives – arises primarily out of people making connections.

It’s important to recognize that much of the knowledge lies in the experience and ideas of “ordinary” employees rather than solely with specialists in formal innovation departments such as R&D or market research. Increasingly, organizations are trying to tap into such knowledge as a source of innovation via various forms of what can be termed “high-involvement innovation” systems such as suggestion schemes, problem-solving groups, and innovation “jams.”

View 6.1 explores the approach taken in one organization.

Mobilizing “high-involvement innovation” – tapping into the ideas of employees – is a long-standing and powerful approach, as we saw in Chapter 3. New technologies around intranets and the parallel trend toward greater social networking mean that many suggestion schemes are being given a new lease on life. For example, France Telecom (the parent for the Orange mobile phone business) has been running its idee cliq scheme for several years and now routinely gets around 30,000 ideas every day from its employees [64].

One rich seam in this involves the entrepreneurial ideas of employees – projects that are not formally sanctioned by the business but that build on the energy, enthusiasm, and inspiration of people passionate enough to want to try out new ideas. Encouraging internal entrepreneurship – “intrapreneurship” as it has been termed [65] – is increasingly popular, and organizations such as 3M and Google make attempts to manage it in a semiformal fashion, allocating a certain amount of time/space to employees to explore their own ideas [66]. Managing this is a delicate balancing act – on the one hand, there is a need to give both permission and resources to enable employee-led ideas to flourish, but on the other, there is the risk of these resources being dissipated with nothing to show for them.

In many cases, there is an attempt to create a culture of what can be termed “bootlegging” in which there is tacit support for projects that go against the grain [67]. An example in BMW – where these are called “U-boat projects” – was the Series 3 Estate version, which the mainstream company thought was not wanted and would conflict with the image of BMW as a high-quality, high-performance, and somewhat “sporty” car. A small group of staff worked hard in their own time on this, even at one stage using parts cannibalized from an old VW Rabbit to make a prototype – and the model has gone on to be a great success and opened up new market space [68].

There has also been an explosion in the use of internal online platforms to encourage and enable idea submission, development, and acceleration.

Extending External Connections

The principle of spreading the net widely is well established in innovation studies as a success factor – and places emphasis on building strong relationships with key stakeholders. An IBM survey of 750 CEOs around the world 76% ranked business partner and customer collaboration as top sources for new ideas while internal R&D ranked only eighth. The study also indicated that “outperformers” – in terms of revenue growth – used external sources 30% more than underperformers did. It’s not hard to see why – the managers interviewed listed the clear benefits from collaboration with partners as things such as reduced costs, higher quality, and customer satisfaction, access to skills and products, increased revenue, and access to new markets and customers. As one CEO put it, “We have at our disposal today a lot more capability and innovation in the marketplace of competitive dynamic suppliers than if we were to try to create on our own,” while another stated simply “If you think you have all of the answers internally, you are wrong.”2

This emphasizes the need both for better use of existing mainstream innovation agents – for example sales or purchasing as channels to monitor and bring back potential sources of innovation – and for establishing new roles and structures. In the former case, there is already strong evidence of the importance of customers and suppliers as sources of innovation and the key role that relevant staff have in managing these knowledge sources. In the field of process innovation, for example, where the “lean” agenda of improving on cost, quality, and delivery is a key theme, there is strong evidence that diffusion can be accelerated through supply chain learning initiatives [69,70].

View 6.2 describes approaches being taken by a wide range of organizations to extend their search capabilities.

As View 6.2 shows, the “open-innovation” challenge also points us to where further experimentation is needed to make new connections. Strategies used are presented in the upcoming sections.

Sending Out Scouts

This is a widely used strategy that involves sending out people (full- or part-time) whose role is to search actively for new ideas to trigger the innovation process. (In German, they are called ideenjager – idea hunters – a term that captures the concept well.) They could be searching for technological triggers, emerging markets or trends, competitor behavior, and so on, but what they have in common is a remit to seek things out, often in unexpected places. Search is not restricted to the organization’s particular industry; on the contrary, the fringes of an industry or even currently entirely unrelated fields can be of interest.

For example, the UK telecom company BT has a scouting unit in Silicon Valley, which assesses some 3000 technology opportunities a year in California. The four-man operation was established in 1999 to make venture investments in promising telecom start-ups, but after the dotcom bubble burst, it shifted its mission toward identifying partners and technologies that BT was interested in. The small team looks at more than 1000 companies per year, and then, based on their deep knowledge of the issues facing the R&D operations back in England, they target the small number of cases where there is a direct match between BT’s needs and the Silicon Valley company’s technology. While the number of successful partnerships that result from this activity is small – typically 4 or 5 per year – the unit serves an invaluable role in keeping BT abreast of the latest developments in its technology domain [36].

Exploring Multiple Futures

As we saw in Chapter 5, futures studies of various kinds can provide a powerful source of ideas about possible innovation triggers, especially those that do not necessarily follow the current trajectory. Shell’s “Gamechanger” program is a typical example that makes extensive use of alternative futures as a way of identifying domains of interest for future business, which may lie outside the “mainstream” of their current activities. Increasingly, these rich “science fiction” views of how the world might develop (and the threats and opportunities that it might pose in terms of discontinuous innovations) are being constructed by using a wide and deliberately diverse set of inputs rather than the relatively narrow frame of reference that the company staff might bring. One consequence has been the growth of specialist service companies that offer help in building and exploring models of alternative futures.

For example, Novo Nordisk, a major Danish pharmaceuticals business, makes use of a company-wide scenario-based program to explore radical futures around their core business. Its “Diabetes 2020” process involved exploring radical alternative scenarios for chronic disease treatment and the roles that a player such as Novo Nordisk could play. As part of the follow-up from this initiative, in 2003, the company helped set up the Oxford Health Alliance, a nonprofit collaborative entity that brought together key stakeholders – medical scientists, doctors, patients, and government officials – with views and perspectives that were sometimes quite widely separated. To make it happen, Novo Nordisk made clear that its goal was nothing less than the prevention or cure of diabetes – a goal that if it were achieved would potentially kill off the company’s main line of business. As Lars Rebien Sørensen, the CEO of Novo Nordisk, explained:

“In moving from intervention to prevention – that’s challenging the business model where the pharmaceuticals industry is deriving its revenues! … We believe that we can focus on some major global health issue – mainly diabetes – and at the same time create business opportunities for our company.”

Another related approach is to build “concept” models and prototypes to explore reactions and provide a focus for various different kinds of input that might shape/cocreate future products and services. Concept cars are commonly used in the automotive industry not as production models but as stepping stones to help understand and shape what will be products in the future. Similarly, Airbus and other aerospace firms have concept aircraft, while Toyota is working on concept projects around housing, transportation, and energy systems.

More recently, companies have started to see value in developing such scenarios jointly with other organizations and discover exciting opportunities for cross-industry collaboration (which often means the creation of an entirely new market).

Keeping an Eye on Innovation Markets

At one level, the Internet offers a vast library of innovation markets – and the mechanisms to make new connections to and among the information it contains. This is, naturally, a widely used approach, but it is interesting to look a little more deeply at how particular forms are developing and shaping this powerful tool.

In its simplest form, the Web is a passive information resource to be searched – an additional space into which the firm might send its scouts. Increasingly, there are professional organizations who offer focused search capabilities to help with this hunting – for example, in trying to pick up on emerging “cool” trends among particular market segments. High-velocity environments such as mobile telecoms, gaming, and entertainment depend on picking up early warning signals and often make extensive use of these search approaches across the Web.

Developments in communications technology also make it possible to provide links across extranets and intranets to speed up the process of bringing signals into where they are needed. Firms such as Zara and Benetton have sophisticated IT systems giving them early warning of emergent fashion trends, which can be used to drive a high-speed flexible response on a global basis.

This rich information source aspect can quickly be amplified in its potential if it is seen as a two-way or multiway information marketplace. One of the first companies to take advantage of this was Eli Lilly, who set up Innocentive.com as a match-making tool, connecting those with scientific problems with those being able to offer solutions. As Innocentive CEO Darrel Carroll says, “Lilly hires a large number of extremely talented scientists from around the world, but like every company in its position, it can never hire all the scientists it needs. No company can.” There are now multiple sites offering a brokering service, linking needs and means, and essentially creating a global marketplace for ideas – in the process providing a rich source of early warning signals.

Research Note 6.2 discusses the use of innovation markets and broadcast search.

A further extension of this concept is to use websites in a more open-ended fashion, as laboratories in which experiments can be conducted or prototypes tested. For example, BMW makes use of the Web to enable a “Virtual Innovation Agency” – a forum where suppliers from outside the normal range of BMW players can offer ideas that BMW may be able to use. Although this carries the risk that many “cranks” will offer ideas, these may also provide stepping stones to new domains of interest.

Working with Active Users

As we saw earlier, an increasingly significant strategy involves seeing users not as passive consumers of innovations created elsewhere but rather as active players in the process. Their ideas and insights can provide the starting point for very new directions and create new markets, products, and services. The challenge now is to find ways of identifying and working with such lead users.

One of the clues is that active users are often at the fringes of the mainstream – in diffusion theory, they are not even early adopters but rather active innovators. They are tolerant of failure, prepared to accept that things go wrong, but through mistakes, they can get to something better – hence, the growing interest in participating in “perpetual beta” testing and development of software and other online products. More often than not, active users love to get involved because they feel strongly about the product or service in question; they really want to help and improve things. Lego found that the prime motivator among its communities of user-developers was the recognition that came with having their products actually made and distributed. Microsoft maintains a group of so-called Microsoft buddies – about 1500 power users of their products such as Web masters, programmers, software vendors, and so on. Strong ties to these customers support Microsoft. They participate in beta testing, help to improve existing products, and submit ideas for new functionalities. The users get no monetary rewards, but receive free software and are invited to biannual meetings. To prevent a “not-invented-here” problem within Microsoft’s internal development teams, special liaison officers act as bridges between the “buddies” and the development teams of the company.

“Deep Diving”

Most market research has become adept at hearing the “voice of the customer” via interviews, focus groups, panels, and so on. But sometimes what people say and what they actually do is different. In recent years, there has been an upsurge in the use of anthropological style techniques to get closer to what people need/want in the context in which they operate. “Deep dive” is one of many terms used to describe the approach – “empathic design” and “ethnographic methods” are others [71].

Much of the research toolkit here originates from the field of anthropology where the researcher aims to gain insights primarily through observation and immersing himself or herself in the day-to-day life of the object of study – rather than through questioning only. For example, to ensure that their new terminal at Heathrow would address user needs well into the future, BAA commissioned some research into who users in 2020 might look like and what their needs might be. Of course, the aging population came up as an issue; focusing on the behavior of old people at the airport, they noticed that old people tend to go to the toilet rather frequently. So, the conclusion was to plan for more toilets at Terminal 5. However, when someone really followed people around, they noted that many people going to the restrooms did not actually use the toilet – but went there because it was quiet, and they could actually hear the announcements!

Probing and Learning

One of the problems about a radically different future is that it is hard to imagine it and hard to predict how things will play out. Sometimes, a powerful approach is to try something out – probe – and learn from the results, even if they represent a “failure.” In this way, emergent trends, potential designs, and so on can be explored and refined in a continuing learning process.

There are two complementary dimensions here – the concept of “prototyping” as a means of learning and refining an idea and the concept of pilot-scale testing before moving across to a mainstream market. In both cases, the underlying theme is essentially one of “learning as you go,” trying things out, making mistakes but using the experience to get closer to what is needed and will work. As Geoff Penney, Chief Information Officer of the US-based investment house Charles Schwab once said, “To avoid running too much risk we run pilots, and everyone knows it is ‘just’ a pilot and is not afraid of making suggestions for improvement – or killing it.”

Not surprisingly, prototyping is particularly relevant in product-based firms. For example, Bang & Olufsen has revitalized their prototyping department and made it refer directly to the innovation hub of the company. The prototyping department is engaged in new ideas as early as possible, and the experiences are that this strongly supports the process. And, after a period with disappointing results in applying electronics in toys, LEGO made a change in their development approach toward more intensive use of prototypes. Prototypes were created within a day – often within hours – after the ideas matured. The result was a much more precise dialog within both the organization and the main customers. Eventually, this led to more simple technology – and more success in terms of sales.

But the principles also apply in services – for example, the UK National Health Service and the Design Council have been prototyping new options for dealing with chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart conditions, and Alzheimer’s disease. The aim is to learn by doing and also to engage with the multiple stakeholders who will be part of whatever new system coevolves.

Corporate Venturing

One widely used approach involves setting up of special units with the remit – and more importantly the budget – to explore new diversification options. Loosely termed “corporate venture” (CV) units, they actually cover a spectrum ranging from simple venture capital funds (for internally and externally generated ideas) through to active search and implementation teams, acquisition and spin-out specialists, and so on. For example, Nokia moved beyond “not invented here” to an approach embracing “let’s find the best ideas where ever they are.” Nokia Venturing Organization focuses on corporate venturing activities that include identifying and developing new businesses, or as they put it, “the renewal of Nokia.” Nokia Venture Partners invests exclusively in mobile and Internet protocol (I/P) related start-up businesses. They have a very interesting third group called Innovent that directly supports and nurtures nascent innovators with the hope of growing future opportunities for Nokia.

SAP has set up a venture unit called SAP Inspire to fund start-ups with interesting technologies. The mission of the group is to “be a world-class corporate venturing group that will contribute, through business and technical innovation, to SAP’s long-term growth and leadership.” It does so by,

- seeking entrepreneurial talent within SAP and providing an environment where ideas are evaluated on an open and objective basis;

- actively soliciting and cultivating ideas from the SAP community as well as effectively managing the innovation process from idea generation to commercialization;

- looking for growth opportunities that are beyond the existing portfolio but within SAP’s overall vision and strategy.

The purpose of corporate venturing is to provide some ring-fenced funds to invest in new directions for the business. Such models vary from being tightly controlled (by the parent organization) to being fully autonomous. (Chapter 12 discusses this approach in detail.)

Using Brokers and Bridges

As we saw earlier, innovation can often take a “recombinant” form – and the famous saying of William Gibson is relevant here – “the future is already here, it’s just unevenly distributed.” Much recent research work on networks and broking suggests that a powerful search strategy involves making or facilitating connections – “bridging small worlds.” Increasingly, organizations are looking outside their “normal” knowledge zones as they begin to pursue “open-innovation” strategies. But sending out scouts or mobilizing the Internet can result simply in a vast increase in the amount of information coming at the firm – without necessarily making new or helpful connections. There is a clear message that networking – whether internally across different knowledge groups – or externally – is one of the big management challenges in the twenty-first century. Increasingly, organizations are making use of social networking tools and techniques to map their networks and spot where and how bridges might be built – and this is a source of a growing professional service sector activity. Firms such as IDEO specialize in being experts in nothing except the innovation process itself – their key skill lies in making and facilitating connections [71].

A number of new brokers today use the Internet to facilitate innovation. We have already mentioned Innocentive, and other Web-based brokers are companies such as NineSigma and YET2.com, who provide bridging capabilities for (external) inventors with ideas or concepts to corporate development units. Others operate in a more direct broking mode, acting as “marriage brokers” introducing partners and facilitating connections – examples include 100% Open and the Innovation Exchange.

Summary

- Faced with a rich environment full of potential sources of innovation, individuals and organizations need a strategic approach to searching for opportunities.

- We can imagine a search space for innovation within which we look for opportunities. There are two dimensions – “incremental/do better vs. radical/do different innovation” and “existing frame/new frame.”

- Looking for opportunities can take us into the realms of “exploit” – innovations built on moving forward from what we already know in mainly incremental fashion. Or, it can involve “explore” innovation, making risky but sometimes valuable leaps into new fields and opening up innovation space.

- Exploit innovation favors established organizations and start-up entrepreneurs who mostly find opportunities within niches in an established framework.

- Bounded exploration involves radical search but within an established frame. This requires extensive resources – for example, in R&D – but although this again favors established organizations, there is also scope for knowledge-rich entrepreneurs – for example, in high-tech start-up businesses.

- Reframing innovation requires a different mind-set, a new way of seeing opportunities – and often favors start-up entrepreneurs. Established organizations find this area difficult to search in because it requires them to let go of the ways they have traditionally worked – in response, many set up internal entrepreneurial groups to bring the fresh thinking they need.

- Exploring at the edge of chaos requires skills in trying to “manage” processes of coevolution. Again this favors start-up entrepreneurs with the flexibility, risk-taking, and tolerance for failure to create new combinations and the agility to pick up on emerging new trends and ride them.

- Search strategies require a combination of exploit and explore approaches, but these often need different organizational arrangements.

- There are many tools and techniques available to support search in exploit and explore directions; increasingly, the game is being opened up, and networks (and networking approaches and technologies) are becoming increasingly important.

- Absorptive capacity – the ability to absorb new knowledge – is a key factor in the development of innovation management capability. It is essentially about learning to learn.

Chapter 6: Concept Check Questions

- For successful innovation the ratio between “exploit” and “explore” search behavior should be 80%/20%.

- Which of these is not an aspect of knowledge flow for innovation?

- Which of these is not a search pattern associated with emergence and reframing?

- Opsen innovation is a two way process in which an organization’s knowledge base is made available to others while at the same time the firm can find new sources of potentially useful knowledge from outside.

- Which of these is not an aspect of absorptive capacity in organizations as seen by Zahra and George’s model?

Further Reading