CHAPTER 14

Capturing Social Value

So far, we have focused mainly on how firms can better capture the benefits of innovation, but arguably innovation has an even more profound influence on fundamental economic and social development. In this chapter, we briefly review some of the relationships between innovation and economic and social development and argue that there is much potential for innovation to make a more significant, positive contribution to emerging economies, social service, and sustainability.

14.1 Building BRICs – The Rise of New Players on the Innovation Stage

The current wave of innovation expansion has seen a focus on key countries known as BRIC – Brazil, Russia, India, and China – but there are many other smaller economies surging into the same space – for example, Kazakhstan or South Africa. They share a mixture of rich resource endowments, relatively young populations, large potential domestic markets, reasonably developed infrastructure, and a technological base, which provides them with a platform for growing and building innovation capability to play on the wider global stage.

In his best-selling book, The world is flat: The globalized world in the 21st century, Thomas Friedman argues that developments in technology and trade, in particular information and communications technologies (ICTs), are spreading the benefits of globalization to the emerging economies, promoting their development and growth [1]. This optimistic thesis is appealing, but the evidence suggests the picture is rather more complex, for the following reasons:

- Firstly, technology and innovation are not evenly distributed globally and are not easily packaged and transferred across regions or firms. For example, only about a quarter of the innovative activities of the world’s largest 500, technologically active firms are located outside their home countries [2].

- Secondly, different national contexts significantly influence the ability of firms to absorb and exploit such technology and innovation. For example, state ownership and availability of venture capital both influence entrepreneurship [3].

- Thirdly, the position of firms in international value chains can profoundly constrain their ability to capture the benefits of their innovation and entrepreneurship. Many firms in emerging economies have become trapped in dependent relationships as low-cost providers of low-technology, low-value manufactured goods or services, and have failed to develop their own design or new products [4].

Therefore, development of firms from emerging economies is much more than simply “catching up” with those in the more advanced economies and is not (only) the challenge of moving from “followers” to “leaders.” Global standards and position in international value chains can constrain the ability of firms based in emerging economies to upgrade their capabilities and appropriate greater value, but they also present ways in which these firm can innovate to overcome these hurdles, for example, by using international standards as a catalyst for change or by repositioning themselves in local clusters or global networks. By position, we mean the current endowment of technology and intellectual property of a firm, as well as its relations with customers and suppliers.

Innovation and enterprise are central to the development and growth of emerging economies, and yet their contribution is usually considered in terms of the most appropriate national policy and institutions or the regulation of international trade. Macroeconomic issues are important, and national systems of innovation, including formal policy, institutions, and governance, can have a profound influence on the degree and direction of innovation and enterprise in a country or region, but it is also critical to consider a more micro perspective, in particular innovation by firms and the entrepreneurship of individuals.

Firms in emerging economies may pursue different routes to upgrading through innovation [5]:

- Process upgrading Making incremental process improvements to adapt to local inputs, reduce costs, or improve quality

- Product upgrading Enhancing through adaptation, differentiation, design, and product development

- Capability upgrading Improving the range of functions undertaken or changing the mix of functions, for example, production versus development or marketing

- Intersectoral upgrading Moving to different sectors, for example, to those with higher value added

To some extent, firms in emerging economies face a “reverse product–process innovation life cycle.” We saw in Chapter 1 that the most common pattern of evolution of technological innovation in the industrialized world has been from product to process innovation, on the one hand, and from radical to incremental innovation, on the other. Initially, a series of different radical product innovations emerge and compete in the market, but as the innovations and markets evolve together, a “dominant design” begins to emerge, and the locus of innovation shifts from product to process and from radical to more incremental improvements in cost and quality. However, in emerging economies, the path of evolution is often reversed and begins with incremental process innovations, to produce an existing product at a lower cost or at a lower quality for different market. As firms improve their capabilities, they may then begin to make product adaptations and changes in design and eventually move toward more radical product innovation.

This has important implications for the type of capabilities firms need to develop. For example, at first, the emphasis should be on incremental process improvement and development, which suggests innovation in production and organization, rather than technological development or formal R&D (see Case Study 14.1 for examples of service innovation in India). This suggests a hierarchy of capabilities or learning, each adding greater value.

A similar pattern can be seen in Russia, where there has been substantial growth in software – see View 14.1.

A characteristic of BRIC and other emerging economies is that they are simultaneously very advanced in terms of industrial and market development and at the same time often still at an early stage of development. India, for example, has satellite technology, a global pharmaceuticals industry, and some market leading corporations, but it also has huge problems of health care, illiteracy, and basic infrastructure. And other countries – notably in Africa and much of Latin America – are still at a relatively early stage in their development of innovation capability.

But these conditions do not mean there is no scope for innovation – indeed, there has been something of a revolution in thinking as we have come to realize that learning to meet the particular needs for goods and services in these spaces may actually offer radical new alternative pathways for innovation in more industrialized setting. In particular, the concept of “frugal innovation” (which we saw in Chapter 5) has particular relevance in the context of emerging economies with limited skills and resources [6].

Research Note 14.1 gives an example.

In his influential 2006 book The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, C. K. Prahalad pointed out that most of the world’s population – around 4 billion people – live close to or below the poverty line, with an average income of less than $2/day [7]. It is easy to make assumptions about this group along the lines of “they can’t afford it so why innovate?” In fact, the challenge of meeting their basic needs for food, water, shelter, and health care require high levels of creativity – but beyond this social agenda lies a considerable innovation opportunity, as we saw in Chapter 5. But it requires a reframing of the “normal” rules of the market game and a challenging of core assumptions.

Solutions to meeting these needs will have to be highly innovative, but the prize is equally high – access to a high-volume/low-margin marketplace. For example, Unilever realized the potential of selling their shampoos and other cosmetic products not in 250 ml bottles (which were beyond the price range of most “bottom of the pyramid” (BoP) customers) but in single sachets. The resulting market growth has been phenomenal, and examples such as this are fueling major activity among large corporations looking to adapt their products and services to serve the BoP market.

In Kenya, the MPESA system was originally developed to increase security – if a traveler wishes to move between cities, he or she will not take money but instead forward it via mobile phone in the form of credits, which can then be collected from the phone recipient at the other end. Mobile money solutions such as ApplePay began to be introduced in the United States and Europe around 2014, but MPESA was by then well established; Africa leads the world in mobile payment use with 9 countries having more mobile accounts than conventional bank accounts.

View 14.2 gives an example drawn from the FT Transformational Business Awards.

Significantly, the needs of this BoP market cover the entire range of human wants and needs, from cosmetics and consumer goods through to basic health care and education. Prahalad’s original book contains a wide range of case examples where this is beginning to happen and which indicate the huge potential of this group – but also the radical nature of the innovation challenge. Subsequently, there has been significant expansion of innovative activity in these emerging market areas – driven in part by a realization that the major growth in global markets will come from regions with a high BoP profile.

Case Study 14.2 gives an example of the BoP approach.

14.2 Innovation and Social Change

There are many definitions of social innovation and entrepreneurship, but most include two critical elements:

- The aim is to create social change and value, rather than commercial innovation and financial value. Conventional commercial entrepreneurship often results in new products and services and growth in the economy and employment, but social benefits are not the explicit goal.

- It involves business-, public-, and third-sector organizations to achieve this aim. Conventional commercial entrepreneurship tends to focus on the individual entrepreneur and new venture, which occupy the business sector, although organizations in the public or third sectors may be stakeholders or customers.

Examples of applications of social innovation and entrepreneurship include the following:

- Poverty relief

- Community development

- Health and welfare

- Environment and sustainability

- Arts and culture

- Education and employment

However, social innovation is not simply innovation in a different context. Traditional public- and third-sector organizations have often failed to deliver improvement or change because of the constraints of organization, culture, funding, or regulation. For example, in many public- and third-sector organizations, the needs of the funders or employees may become more important to satisfy compared to the needs of their target community.

Therefore, social entrepreneurs share most of the characteristic of entrepreneurs (see Chapter 12), but are different in some important respects:

- Motives and aims – less concerned with independence and wealth, and more concerned with social means and ends

- Timeframe – less emphasis on short-term growth and longer-term harvesting of the venture, and more concern on long-term change and enduring heritage

- Resources – less reliance on the firm and management team to execute the venture, and greater reliance on a network of stakeholders and resources to develop and deliver change

Key characteristics that appear to distinguish social entrepreneurs from their commercial counterparts include a high level of empathy and need for social justice. The concept of empathy is complex, but includes the ability to recognize and emotionally share the feelings and needs of others, and is associated with a desire to help. However, while empathy and a need for social justice may be necessary attributes of a social entrepreneur, they are not sufficient. These may make a social venture desirable, but not necessarily feasible [8]. The feasibility will be influenced by not only the personal characteristics of an entrepreneur, such as background and personality, but also some contextual factors more common in public- and third-sector organizations (see Case Study 14.3 for an example).

Potential barriers to social entrepreneurship include the following:

- Access to and support of local networks of social and community-based organizations, for example, relationships and trust in informal networks.

- Access to and support of government and political infrastructure, for example, nationality or ethnic restrictions.

Of course, it is not simply a matter of individuals and start-up ventures. As we’ve seen throughout the book, entrepreneurial behavior can be found in any organization and is central to the ability to develop and reinvent. In the field of social entrepreneurship, a growing number of businesses are recognizing the possibilities of pursuing parallel and complementary trajectories, targeting both conventional profits and social value creation.

Social innovation is also an increasingly important component of “big business,” as large organizations realize that they can secure a license to operate only if they can demonstrate some concern for the wider communities in which they are located. (The recent backlash against the pharmaceutical firms as a result of their perceived policies in relation to drug provision in Africa is an example of what can happen if firms don’t pay attention to this agenda.) “Corporate social responsibility” (CSR) is becoming a major function in many businesses, and many make use of formal measures – such as the “triple bottom line” – to monitor and communicate their focus on more than simple profit making.

By engaging stakeholders directly, companies are also better able to avoid conflicts or to resolve them when they arise. In some cases, this involves directly engaging activists who are leading campaigns or protests against a company. For example, Starbucks responded to customers’ concerns and activist protests about the impact of coffee growing on songbirds by partnering with leading activist groups to improve organic, bird-friendly coffee production methods, setting up a pilot sourcing program, and further increasing public awareness. The conflict was resolved, and Starbucks established itself as a leader on this issue.

Ahold, the largest retailer in the Netherlands, has also used stakeholder engagement to enable it to expand its operations into underserved urban areas. The company realized that on its own it would not be able to operate successfully and would need to work with the government and other companies to create a “sound investment climate” locally. With the local government and 9 other retailers, it developed a comprehensive development plan for the Dutch town of Enschede.

Sometimes, there is scope for social entrepreneurship to spin out of mainstream innovative activity. Procter & Gamble’s PUR water purification system offers radical improvements to point-of-use drinking water delivery. Estimates are that it has reduced intestinal infections by 30–50%. The product grew out of research in the mainstream detergents business, but the initial conclusion was that the market potential of the product was not high enough to justify investment; by reframing it as a development aid, the company has improved its image but also opened up a radical new area for working.

It is easy to become cynical about CSR activity, seeing it as a cosmetic overlay on what are basically the same old business practices. But there is a growing recognition that pursuing social entrepreneurship-linked goals may not be incompatible with developing a viable and commercially successful business. A survey by consultants A.D. Little uses the metaphor of a journey that begins with simple compliance innovation – the “license to operate” argument. Many companies have now moved into the “foothills” of the “beyond compliance” area where they are realizing that they have to deal with key stakeholders and that in the process some interesting innovation opportunities can emerge (see Case Study 14.4). But the real challenge is to move onto the innovation high ground of full-scale stakeholder innovation, “creating new products and services, processes and markets which will respond to the needs of future as well as current customers” [9].

So how does this play out in the case of social innovation and entrepreneurship? Table 14.1 gives some examples of the challenges and potential responses.

TABLE 14.1 Challenges in Social Entrepreneurship

| What Has to Be Managed …. | Challenges in Social Entrepreneurship |

| Search – recognizing opportunities |

Many potential social entrepreneurs (SEs) have the passion to change something in the world – and there are plenty of targets to choose from, such as poverty, access to education, health care, and so on. But passion isn’t enough – they also need the classic entrepreneur’s skill of spotting an opportunity, a connection, a possibility, which could develop. It’s about searching for new ideas that might bring a different solution to an existing problem – for example, the microfinance alternative to conventional banking or street-level moneylending. As we’ve seen elsewhere in the book, the skill is often not so much discovery – finding something completely new – as connection – making links between disparate things. In the SE field, the gaps may be very wide – for example, connecting rural farmers to high-tech international stock markets requires considerably more vision to bridge the gap than spotting the need for a new variant of futures trading software. So SEs need both passion and vision, plus considerable broking and connecting skills. |

| Selection and resource mobilization |

Spotting an opportunity is one thing – but getting others to believe in it and, more importantly, back it is something else. Whether it’s an inventor approaching a venture capitalist or an internal team pitching a new product idea to the strategic management in a large organization, the story of successful entrepreneurship is about convincing other people. In the case of SE, the problem is compounded by the fact that the targets for such a pitch may not be immediately apparent. Even if you can make a strong business case and have thought through the likely concerns and questions, who do you approach to try and get backing? There are some foundations and no-profit organizations, but in many cases, one of the important skill sets of an SE is networking, the ability to chase down potential funders and backers and engage them in their project. Even within an established organization, the presence of a structure may not be sufficient. For many SE projects, the challenge is that they take the firm in very different directions, some of which fundamentally challenge its core business. For example, a proposal to make drugs cheaply available in the developing world might sound a wonderful idea from an SE perspective – but it poses huge challenges to the structure and operations of a large pharmaceutical firm with complex economics around R&D funding, distribution, and so on. It’s also important to build coalitions of support – securing support for social innovation is very often a distributed process, but power and resource are often not concentrated in hands of single decision-maker. There may also not be a “Board” or venture capitalist to pitch the ideas to – instead, it is a case of building momentum and groundswell. And there is a need to provide practical demonstrations of what otherwise might be seen as idealistic “pipedreams.” The role of pilots, which then get taken up and gather support, is well proven – for example, the Fair Trade model or microfinance. |

| Developing the venture |

Social innovation requires extensive creativity in getting hold of the diverse resources to make things happen – especially since the funding base may be limited. Networking skills become critical here – engaging different players and aligning them with the core vision. One of the most important elements in much social innovation is scaling up – taking what might be a good idea implemented by one person or in a local community and amplifying it so that it has widespread social impact. For example, Anshu Gupta’s original idea was to recycle old clothes found on rubbish dumps or cast away to help poor people in his local community. Beginning with 67 items of clothing, the idea has now been scaled so that he and his organization collect and recycle 40,000 kg of clothes every month across 23 states in India. The principle has been applied to other materials – for example, recycling old cassettes to make mats and soft furnishings. (See http://www.goonj.org/) |

| Innovation strategy | Here the overall vision is critical – the passionate commitment to a clear vision can engage others – but social entrepreneurs can also be accused of idealism and “having their head in the clouds.” Consequently, there is a need for a clear plan to translate the vision step-by-step into reality. |

| Innovative organization/rich networking | Social innovation depends on loose and organic structures where the main linkages are through a sense of shared purpose. At the same time, there is a need to ensure some degree of structure to allow for effective implementation. The history of many successful social innovations is essentially one of networking, mobilizing support, and accessing diverse resources through rich networks. This places a premium on networking and broking skills. |

14.3 The Challenge of Sustainability-led Innovation

In an influential report, the WWF pointed out that lifestyles in the developed world at present require the resources of around two planets, and if emerging economies follow the same trajectory, this will rise to 2.5 by 2050 [10]. Many key energy and raw material resources are close to passing their “peak” of availability and will become increasingly scarce [11]. At the same time, the dangers of global warming have moved to center stage, and climate change (and how to deal with it) is an urgent political as well as economic issue. This translates to increasingly strong legislation forcing organizations to change their products and processes to reduce carbon footprint, greenhouse gas emission, and energy consumption. Behind this is the growing challenge of environmental pollution and the concern to not only stop the increasing damage being done to the natural environment but also reverse the impacts of earlier practices [12].

Innovation is often presented as a major contribution to the degradation of the environment, through its association with increased economic growth and consumption [13]. However, innovation can also be a large part of any potential solution to a range of environmental issues, including the following:

- Cleaner products – with a lower environmental impact over their life cycle

- More efficient processes – to minimize or treat waste, to reuse or recycle

- Alternative technologies – to reduce emissions, provide renewable energy

- New services – to replace or reduce consumption of products

- Systems innovation – to measure and monitor environmental impact, new sociotechnical systems

Research Note 14.2 looks at some market opportunities in sustainability-led innovation (SLI).

As the writer C. K. Prahalad put it, “… sustainability is a mother lode of organizational and technological innovations that yield both bottom-line and top-line returns. Becoming environment-friendly lowers costs because companies end up reducing the inputs they use. In addition, the process generates additional revenues from better products or enables companies to create new businesses. In fact, because [growing the top and bottom lines] are the goals of corporate innovation, we find that smart companies now treat sustainability as innovation’s new frontier” [16].

Case Study 14.5 describes experience at Interface, a large floor-coverings company.

Early activity in the field of SLI centered around “cosmetic” activity in which organizations sought to improve their image or strengthen their CSR image through high-profile activities designed to show their “green” credentials. But now it has moved to a second phase in which increasingly strong legislation provides a degree of forced compliance. The frontier is now one along which leading organizations are seeking to exploit opportunities, as they recognize the need for innovation to deal with resource instability and scarcity, energy security, and systemic efficiencies across their supply chains.

A number of frameworks have been proposed to take account of this – for example, Prahalad and Nidumolo suggest five steps moving from “viewing compliance as an opportunity,” through “making value chains sustainable” and “designing sustainable products and services,” to “designing new business models.” Their fifth stage focuses on “creating next practice platforms” – implying a system-level change [16]. For entrepreneurs, these opportunities offer significant options for new ventures in the sustainability space around resources, energy, and environmental management.

We can use the “4Ps” framework from Chapter 1 to classify the kinds of activity going on around SLI. Table 14.2 gives some examples.

TABLE 14.2 Examples of Sustainability-led Innovation

| Innovation Target | Examples |

| Product/service offering | “Green” products, design for greener manufacture and recycling, service models replacing consumption/ownership models |

| Process innovation | Improved and novel manufacturing processes, lean systems inside the organization and across supply chain, green logistics |

| Position innovation | Rebranding the organization as “green,” meeting the needs of underserved communities – for example, bottom of pyramid |

| “Paradigm” innovation – changing business models | System-level change, multiorganization innovation, servitization (moving from manufacturing to service emphasis) |

14.4 A Framework Model for Sustainability-led Innovation

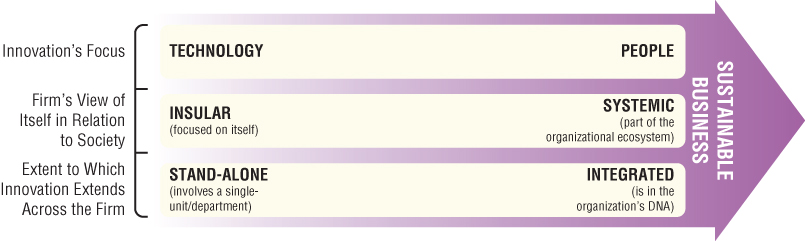

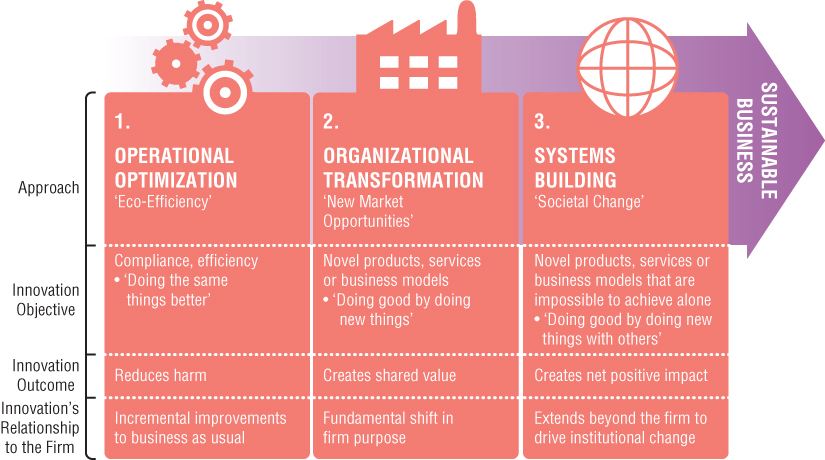

Figure 14.1 illustrates one way of looking at the move toward SLI, seeing it as involving three dimensions that underpin a change in the overall approach from treating the symptoms of a problem to eventually working with the system in which the problem originates. It is based on an extensive research project carried out with the Network for Business Sustainability, a Canadian organization that works extensively with large companies such as RIM, Suncor, SAP, BC Hydro, and Unilever and academic institutions such as the Richard Ivey School of Business [17].

FIGURE 14.1 The journey toward sustainability-led innovation.

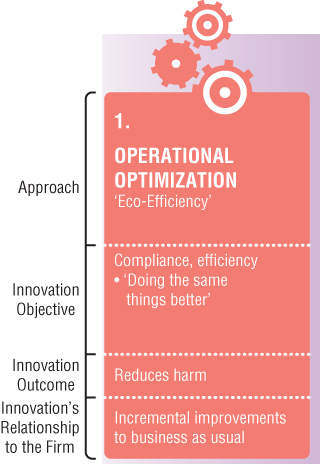

With that framework in the background, we can think of three stages in the evolution of SLI:

Step 1 is “operational optimization” – essentially doing what we do but better. Table 14.3 gives some examples.

TABLE 14.3 Operational Optimization

| Definition | Characteristics | Examples |

| Compliance with regulations or optimized performance through increased efficiency | In the stage of operational optimization, the organization actively reduces its current environmental and social impacts without fundamentally changing its business model. In other words, an optimizer innovates in order to “do less harm.” Innovations are typically incremental, addressing a single issue at a time. And they tend to favor the “technofix” – focusing on new technologies as ways to reduce impacts while maintaining business as usual. Innovation tends to be inward-focused in both development and outcome; at this stage, companies typically rely on internal resources to innovate, and the resulting innovations are company-centric: their intent is primarily to reduce costs or maximize profits |

Pollution controls Flexible work hours/telecommuting Waste diversion Shutting or consolidating facilities Energy-efficient lighting Use of renewable energy Reduced paper consumption Reduced packaging Decreased use of raw materials Reduced use/elimination of hazardous materials Optimization of product size/weight for shipping Hybrid electric fleet vehicles Delivery boxes redesigned from single to multiuse |

Step 2 is “organizational transformation” – essentially doing different at the level of the organization.

Table 14.4 gives more details.

TABLE 14.4 Organizational Transformation

| Definition | Characteristics | Examples |

| The creation of often disruptive new products and services by viewing sustainability as a market opportunity | Rather than focusing on “doing less harm,” organizational transformers believe that their organization can benefit financially from “doing good.” They see opportunities to serve new markets with novel, sustainable products, or they are new entrants with business models predicated on creating value by lifting people out of poverty or producing renewable energy. Organizational transformers may focus less on creating products and more on delivering services, which often have a lower environmental impact. They often produce innovations that are both technological and sociotechnical – designed to improve the quality of life for people inside or outside the firm. Transformers are still primarily internally focused in that they see their organization as an independent figure in the economy. However, they do work up and down the value chain and collaborate closely with external stakeholders. The move from operational optimization to organizational transformation requires a radical shift in the mind-set from doing things better to doing new things |

Disruptive new products that change consumption habits – for example, a camp stove that turns any biomass into a hyper-efficient heat source and whose sales subsidize cheaper models distributed in developing countries Disruptive new products that benefit people – for example, CT scanners that are portable and durable and have minimum functionality – making them affordable and useful for health-care providers in developing countries Replacing products with services – for example, leasing and maintaining carpets over a prescribed lifetime rather than selling them Introducing car- and bike-sharing services in urban centers to reduce pollution caused by individual car ownership while increasing overall mobility Replacing physical services with electronic services – for example, reducing paper consumption by delivering bills electronically rather than by mail Services with social benefits – for example, a smart phone app that rewards people with coupons for local merchants when they make charitable donations |

View 14.3 looks at SLI within Philips.

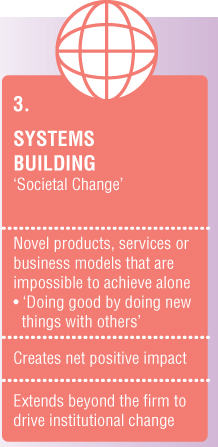

Step 3 is about changing the system, coevolving solutions with different stakeholders to create new and sustainable alternatives.

Table 14.5 explores this topic in more detail.

TABLE 14.5 Systems Building

| Definition | Characteristics | Examples |

| The interdependent collaborations between many disparate organizations that create positive impacts on people and the planet |

Systems builders perceive their economic activity as being part of society, not distinct from it. Individually, almost every organization is unsustainable. But taken as a collective, systems can sustain each other. Systems builders extend their thinking beyond the boundaries of the organization to include partners in previously unrelated areas or industries. Because the concept of systems building reflects an unconventional economic paradigm, very few organizations or industries occupy this realm. The move from organizational transformation to systems building requires another radical shift in the mind-set – this time from doing new things and serving new markets to thinking beyond the firm. |

Industrial symbiosis. Disparate organizations cooperate to create a “circular economy” in which one firm’s waste is another’s resources. For example, a construction company uses other companies’ glass waste: the synergies lead to environmental and economic benefits for all. B Corporations. Conceived in the United States but now existing in dozens of countries worldwide. B Corporations are organizations legally obliged to deliver societal benefits. Well-known examples include ice-cream producer Ben & Jerry’s, e-commerce platform Etsy, and cleaning product manufacturers Method and Seventh Generation. |

The whole model looks as follows.

14.5 Responsible Innovation

One message from this theme of sustainability-led innovation is that we need to look more closely at some of the questions we ask during our innovation process. In particular, at the “select” stage, what criteria will we use to make sure that the project is worth pursuing? We saw in Chapter 10 that we need to carefully consider whether or not to take possible innovation ideas forward, and the frameworks we introduced then dealt mainly with risks and rewards. In the public sector, there is additional concern around the “reliability” theme – will the changes we introduce have an impact on our ability to deliver the public services people depend on such as health care and education? But in this chapter, we have seen that there are now urgent additional questions, which we should bring into our decision process around the question of sustainability and wider social impact.

Interestingly, much of the academic and policy-oriented innovation research tradition evolved around such concerns, riding on the back of the “science and society” movement in the 1970s. This led to key institutes (such as the Science Policy Research unit at Sussex University) being established. Their concern – and the many tools that they developed – remained one of challenging the innovation process and particularly questioning the targets toward which it worked [18].

For example, although the global pharmaceutical industry has done much to improve health care through a highly efficient innovation process, there are questions that can be raised around it. Evidence suggests that 90% of its innovation efforts are devoted to the concerns of the richest 10% of the world’s population. In a similar fashion, questions can be asked about innovation systems that can produce impressive consumer electronics yet leave many people in the world short of clean water or access to basic medical care.

The argument is that despite the good intentions of individual researchers and corporations, innovation can sometimes be irresponsible. New products such as the insecticide DDT (developed as a powerful aid to controlling pests) or Thalidomide (a useful antinausea drug) turned out to have unforeseen and seriously negative consequences. In other cases (such as BSE, the Mad Cow disease), pursuit of innovation without adequate safeguards or questions being raised led to major crises. One of the major causes of the global financial crisis – with all the misery it has brought – lay in irresponsible and sometimes reckless financial innovation around tools and techniques. And the current debates around genetically modified (GM) foods and reinvestment in nuclear power to cope with energy shortages remind us of the need to ask questions around innovation.

For these reasons, there is growing interest in developing frameworks that can bring a series of “responsibility” questions into the innovation process and ensure that careful consideration takes place around major change programs [19].

Social and political concerns about the environment and sustainability present a critical, but often subtle, influence on the rate, and more importantly direction, of innovation. Science and technology do have their own internal logics, but development paths and applications are influenced and shaped by broader political, social, and commercial imperatives. In most cases, there are numerous potential technological trajectories, most of which will not be pursued or will fail to become established. For example, nuclear power as a technological innovation has evolved in very different ways in countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Japan. Similarly, innovation in GM crops and foods has taken radically different paths in the United States and Europe, mainly due to public concerns and pressure. Research Note 14.3 discusses some of the more general issues related to managing sustainable innovation.

The conventional approach to innovation and sustainability focuses on how to influence the development and application of innovations through regulation and control. In this approach, formal policies are used in an attempt to direct innovation by using systems of regulation, targets, incentives, and usually punishments for noncompliance. This can be effective, but is a rather blunt instrument to encourage change, and can be slow and incremental.

A more balanced and effective approach tries to understand how technology, markets, and society coevolve through a process of negotiation, consultation, and experimentation with new ways of doing things. This perspective demands a better appreciation of how firms and innovation work and highlights the need to better understand all the organizations involved – the policymakers, consumers, firms, institutions, and other stakeholders that can influence the rate and direction of innovation [20]. By focusing on policy and regulation, the innovation–environment debate and research has not really fully understood or engaged with the motivations and actions of individual entrepreneurs or innovative organizations.

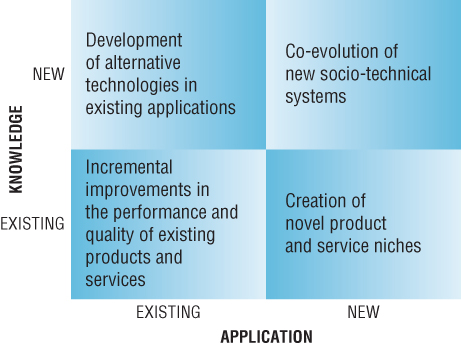

Figure 14.2 presents a typology of the different ways in which innovation can contribute to sustainability [21]. One dimension is the novelty of the knowledge, and the other dimension is the novelty of the application of that knowledge. In the bottom left quadrant, the innovation focuses on the improvement of existing technologies, products, and services. This is not necessarily incremental and may at times involve radical innovation, but the goals and performance criteria remain the same, for example, increasing the fuel efficiency of a power station or car engine. This is the most common type of innovation, and we have discussed this throughout this book. The top left-hand quadrant represents the development of new knowledge, but its application to existing problems. This includes alternative materials, processes, or technologies used in existing products. For example, in energy production and packaging of goods, there are often many alternative competing technologies, with very different properties and benefits. In food packaging, glass, different plastics, aluminum, and steel are all viable alternatives, but each has different energy requirement over their life cycle in their production and reuse or recycling.

FIGURE 14.2 A typology of sustainable innovations.

Moving to the right-hand column, the bottom quadrant represents the application of existing knowledge to create new market niches. These are sometime called architectural innovations, because they reuse different components and subsystems in new configurations. These are very important for sustainable innovation, as typically such innovations emerge and are developed in niches, which initially coexist with the existing mass market, but these niches can mature and grow to influence demand and development in the dominant market (Case Study 14.6). For example, in the car industry, safety was not a significant feature until the early 1980s. Up until that point, the assumption was that “safety did not sell,” and manufacturers were reluctant to develop such features. Corning was initially unable to convince any US manufacturer to adopt laminated windscreens (windshields). However, local demand for improved safety in Scandinavia, especially Sweden, encouraged local manufacturers such as Volvo and Saab to develop and incorporate new safety technologies. These slowly became popular in overseas markets, and competing manufacturers had to respond with similar features. As a result, today, almost all cars have a range of active and passive safety technologies, such as airbags, side-impact protection, crumple zones, antilock brakes, and electronic stability systems.

The top-right quadrant is probably the most fundamental contribution of innovation to sustainability. It is here that new sociotechnical systems coevolve. Developers and users of innovation interact more closely, and many more actors are involved in the process of innovation. In this case, firms are not the only, or even the most important, actor, and the successful development and adoption of such systems innovation demand a range of “externalities,” such as supporting infrastructure, complementary products and services, finance, and new training and skills. For example, the microgeneration of energy requires much more than technological innovation and product development. It requires changes in energy pricing and regulation, an infrastructure to allow the sale of energy back to the grid, and new skills and services in the installation and service of generators. Such innovations typically evolve by a combination of top-down policy change and coordination and bottom-up social change and firm behavior.

Summary

In this chapter, we have looked at some of the wider issues in capturing value to support goals such as economic development, sustainability, and social innovation. While the core business model literature cited in the previous chapter is a good place to start exploring, value creation in these contexts also has some specific resources that are useful.

Chapter 14: Concept Check Questions

- Social entrepreneurship does not concern itself with commercial questions.

- There is no way to resolve the conflict between commercial business goals and those of social innovation.

- Which of the following statements about the “bottom of the pyramid” market is not open to challenge?

- Which of the following is NOT a question for managing social entrepreneurship?

- Which of these is NOT a difference between social entrepreneurs and commercial entrepreneurs?

- Which of these is not a recognized route for sustainability led innovation?

Further Reading

Studies of international development and innovation include Whelan and colleagues’ (2015) Strategic Management and Business Policy: Globalization, Innovation and Sustainability (Pearson), George Yip and Bruce McKern (2016) China’s Next Strategic Advantage: From Imitation to Innovation, MIT Press, and Ramani and colleagues (2014) Innovation in India: Combining Economic Growth with Inclusive Development (Cambridge University Press). Prahalad’s (2013 edition) The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid (Pearson) remains a major challenge to thinking about inclusive innovation.

In the area of sustainability, the Network for Business Sustainability (http://nbs.net/) carries regular reports on research and practice around sustainability and innovation. The theme of “frugal innovation” is becoming increasingly popular, exploring how to innovate in less resource-intensive fashion – see, for example, Rajout and Prabhu’s (2015) Frugal innovation (Economist Books), or Ramdoori and Herstatt (2015) Frugal Innovation in Healthcare: How Targeting Low-Income Markets Leads to Disruptive Innovation (Springer).

Social entrepreneurship is covered in a number of books and reports such as Ken Banks (2016) Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation: International Case Studies and Practice (Kogan Page), Steven Anderson’s (2014) New Strategies for Social Innovation: Market-Based Approaches for Assisting the Poor (Columbia University Press), and Robin Murray and colleagues (2012) The open book of social innovation (The Young Foundation).

NESTA (www.nesta.org.uk) features a wide variety of reports on social innovation and also on the frugal innovation theme.

Case Studies

You can find a number of additional downloadable case studies on the companion website, including the following:

- Spirit, a Russian software firm, which has exploited the strong IT potential in that region

- MPESA as an example of innovation in emerging market economies

- Philips and its extensive journey toward sustainable innovation

- Natura, a Brazilian cosmetics company, which takes sustainability as a core foundation for its products, services, and processes

- Lifeline Energy, which highlights some of the difficulties in developing and sustaining a social innovation venture over time

References

- 1. Friedman, T., The world is flat. 2005, New York: Farra, Strauss, Giroux.

- 2. Hakanos, L. and S. Sjolander, Technology management and international business: Internationalization of R&D and technology. 1992, Chichester: John Wiley.

- 3. Kim, L. and R. Nelson, Technology, learning and innovation: Experiences of newly industrializing economies. 2000, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 4. Schmitz, H., Local enterprises in the global economy. 2004, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- 5. Forbes, N. and D. Wield, From followers to leaders. 2002, London: Routledge.

- 6. NESTA, Frugal innovation. 2012, NESTA National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts: London.

- 7. Prahalad, C.K., The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. 2006, New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing.

- 8. Mair, J., J. Robinson, and K. Hockets, Social entrepreneurship. 2006, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 9. Arthur D. Little Consultants, The business case for corporate responsibility. 2003, ADL Consultants: Cambridge.

- 10. WWF, Living Planet report 2010: Biodiversity, biocapacity and development. 2010, WWF International: Gland, Switzerland.

- 11. Brown, L., World on the edge: How to prevent environmental and economic collapse. 2011, New York: Norton.

- 12. Heinberg, R., Peak everything: Waking up to the century of delcine in earth’s resources. 2007, London: Clairview.

- 13. Kuhl, M., et al., Relationship between innovation and sustainable performance. International Journal of Innovation Management, 2016. 20(6).

- 14. UNEP, Towards a green economy: Pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. 2011, United Nations Environment Programme: Online version http://hqweb.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/88/documents/ger/GER_synthesis_en.pdf.

- 15. WBCSD, Vison 2050. 2010, World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva.

- 16. Nidumolu, R., C. Prahalad, and M. Rangaswami, Why sustainability is not the key driver of innovation. Harvard Business Review, 2009 (September): 57–61.

- 17. Adams, R., et al., Innovating for sustainability: A guide for executives. 2012, Network for Business Sustainability. http://www.nbs.net/knowledge. London, Ontario, Canada.

- 18. Freeman, C., et al., eds. Thinking about the future: A critique of the limits to growth. 1973, Universe Books: New York.

- 19. Owen, R., J. Bessant, and M. Heintz, eds. Responsible innovation. 2013, John Wiley and Sons: Chichester.

- 20. Geels, F., Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case study. Research Policy, 2002. 31(8–9): 1257–1274.

- 21. Smith, A., A. Stirling, and F. Berkhout, The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Research Policy, 2005. 34(10): 1491–1510.