CHAPTER 12

Promoting Entrepreneurship and New Ventures

In Chapter 10, we examined the processes necessary to develop new products and services within the existing corporate environment, based on the strategy and capabilities identified in Chapter 4. In this chapter, we explore how firms develop and commercialize technologies, products, and businesses outside their existing strategy and core competencies. We will discuss the role and management of internal corporate ventures and new ventures in the creation and execution of new technologies, products, and businesses, specifically:

- internal corporate ventures, or “intrapreneurship”

- new ventures and spin-out firms

- factors that influence success and growth

12.1 Ventures, Defined

Ventures, broadly defined, are a range of different ways of developing innovations, alternative to conventional internal processes for new product or service development. We discussed in Chapter 10 the many benefits of using structured approaches to new product and service development, such as stage-gate and development funnel processes. However, these approaches have also a major disadvantage, because decisions at the different gates are likely to favor those innovations close to existing strategy, markets, and products and are likely to filter out or reject potential innovations further from the organization’s comfort zone. For this reason, other mechanisms of development and commercialization are necessary, ranging from internal corporate ventures through to spin-out new ventures.

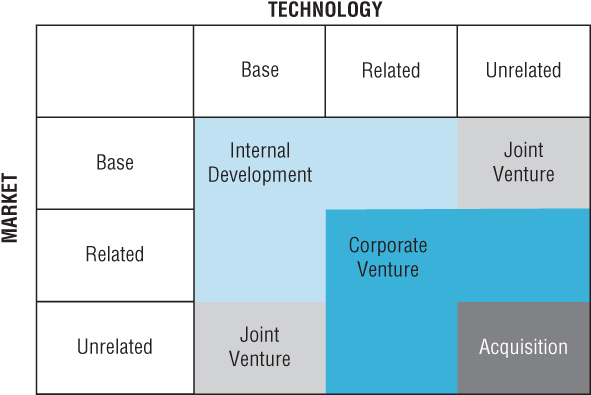

Figure 12.1 suggests a range of venture types that can be used in different contexts. Corporate ventures are likely to be most appropriate where the organization needs to exploit some internal competencies and retain a high degree of control over the business. Joint ventures and alliances involve working with external partners, discussed in the previous chapter, will demand some release of control and autonomy, but in return introduce the additional competencies of the partners. Spin-out or new venture businesses are the extreme case, often necessary where there is little relatedness between the core competencies and new venture business. Note that these options are not mutually exclusive, for example, a spin-out business can become an alliance partner, or a corporate venture can spin-out. Also, all types of venture require a venture champion, a strong business case, and sufficient resources to be successful.

FIGURE 12.1 The role of venturing in the development and commercialization of innovations.

Source: Burgelman, R., Managing the internal corporate venturing process. Sloan Management Review, 1984. 25(2), 33–48.

Profile of a Venture Champion

Research by Ed Roberts [1], who studied 156 new technology-based firms (NTBFs), which were spin-offs from MIT in the United States (herein referred to as “the US study”), and Ray Oakey [2], who examined 131 NTBFs in the United Kingdom (herein referred to as “the UK study”), provide a pretty consistent picture of the profile of a typical venture champion. Despite the obvious Anglo-Saxon bias of these two large studies, other research confirms the general relevance of these factors.

The creation of a venture is the interaction of individual skills and disposition and the technological and market characteristics. The US study emphasizes the role of personal characteristics, such as family background, goal orientation, personality, and motivation; whereas, the UK study stresses the role of technological and market factors. The decision to start an NTBF typically begins with a desire to gain independence and to escape the bureaucracy of a large organization, whether in the public or private sector. Thus, the background, psychological profile, and work and technical experience of a technical entrepreneur interact to contribute to the decision to create an NTBF, as illustrated in Figure 12.2.

FIGURE 12.2 Factors influencing the decision to establish a new venture.

Much of the American research on new ventures, and more general studies of entrepreneurs, tends to emphasize the background and characteristics of a typical entrepreneur. Factors found to affect the likelihood of establishing a venture include:

- family background

- religion

- formal education and early work experience

- psychological profile

A number of studies confirm that both family background and religion affect an individual’s propensity to establish a new venture. A significant majority of technical entrepreneurs have a self-employed or professional parent. Studies indicate that between 50% and 80% have at least one self-employed parent. For example, the US study found that four times as many technical entrepreneurs have a parent who is a professional, compared with other groups of scientists and engineers. The most plausible explanation for this is that the parent acts as a role model and may provide more support for self-employment.

The effect of religious background is more controversial, but it is clear that certain religions are overrepresented in the population of technical entrepreneurs. Whether this observed bias is the result of specific cultural or religious norms, or the result of minority status, is the subject of much controversy but little research. The US study suggests that cultural values are more important than minority status, but even this work indicates that the effect of family background is more significant than religion. In any case, and perhaps more importantly, there appears to be no significant relationship between family and religious background and the subsequent probability of success of an NTBF.

Education and training are major factors that distinguish the founders of NTBFs from other entrepreneurs. The median level of education of technical entrepreneurs in the US study was a master’s degree and, with the important exception of biotechnology-based NTBFs, a doctorate was superfluous. Significantly, the levels of education of technical entrepreneurs do not differentiate them from other scientists and engineers. However, potential technical entrepreneurs tend to have higher levels of productivity than their technical work colleagues, measured in terms of papers published or patents granted: 6.35 versus 2.2 papers on average and 1.6 versus 0.05 patents. This suggests that potential entrepreneurs may be more driven and focussed on outcomes than their corporate counterparts.

In addition to a master’s-level education, on average, a technical entrepreneur will have around 13 years of work experience before establishing an NTBF. In the case of the Route 128 technology cluster in Boston, the entrepreneurs’ work experience is typically with a single incubator organization, whereas technical entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley tend to have gained their experience from a larger number of firms before establishing their own NTBF. This suggests that there is no ideal pattern of previous work experience. However, experience of development work appears to be more important than work in basic research. As a result of the formal education and experience required, a typical technical entrepreneur will be aged between 30 and 40 years when establishing their first NTBF. This is relatively late in life compared to other types of ventures and is due to a combination of ability and opportunity. On the one hand, it typically takes between 10 and 15 years for a potential entrepreneur to attain the necessary technical and business experience. On the other hand, many people begin to have greater financial and family responsibilities at this time. Thus, there appears to be a window of opportunity to start an NTBF in the mid-thirties. Research Note 12.1 discusses the concept of entrepreneurial effectuation, which emphasizes the background and attributes of an entrepreneur.

Much of the research on the psychology of entrepreneurs is based on the experience of small firms in the United States, so the generalizability of the findings must be questioned. However, in the specific case of technical entrepreneurs, there appears to be some consensus regarding the necessary personal characteristics. The two critical requirements appear to be an internal locus of control and a high need for achievement. The former characteristic is common in scientists and engineers, but the need for high levels of achievement is less common. Entrepreneurs are typically motivated by a high need for achievement (so-called “n-Ach”), rather than a general desire to succeed. This behavior is associated with moderate risk-taking, but not gambling or irrational risk-taking. A person with a high n-Ach:

- likes situations where it is possible to take personal responsibility for finding solutions to problems

- has a tendency to set challenging but realistic personal goals and to take calculated risks

- needs concrete feedback on personal performance

However, the US study of almost 130 technical entrepreneurs and almost 300 scientists and engineers found that not all entrepreneurs have high n-Ach, only some do. Technical entrepreneurs had only moderate n-Ach, but low need for affiliation (n-Aff). This suggests that the need for independence, rather than success, is the most significant motivator for technical entrepreneurs. Technical entrepreneurs also tend to have an internal locus of control. In other words, technical entrepreneurs believe that they have personal control over outcomes, whereas someone with an external locus of control believes that outcomes are the result of chance, powerful institutions, or others. More sophisticated psychometric techniques such as the Myers–Briggs type indicators (MBTIs) confirm the differences between technical entrepreneurs and other scientists and engineers.

Numerous surveys indicate that around three-quarters of technical entrepreneurs claim to have been frustrated in their previous job. This frustration appears to result from the interaction of the psychological predisposition of the potential entrepreneur and poor selection, training, and development by the employer. Specific events may also trigger the desire or need to establish an NTBF, such as a major reorganization or downsizing of the parent organization. Case Study 12.1 charts the creation and rise of the app, WhatsApp.

Venture Business Plan

The primary reason for developing a formal business plan for a new venture is to attract external funding. However, it serves an important secondary function. A business plan can provide a formal agreement between founders regarding the basis and future development of the venture. A business plan can help reduce self-delusion on the part of the founders and avoid subsequent arguments concerning responsibilities and rewards. It can help to translate abstract or ambiguous goals into more explicit operational needs and support subsequent decision making and identify trade-offs. Of the factors controllable by entrepreneurs, business planning has the most significant positive effect on new venture performance. However, there are of course many uncontrollable factors, such as market opportunity, which have an even more significant influence on performance [3]. Pasteur’s advice still applies, “… chance favours only the prepared mind.” We discuss the development of business plans in detail in Chapter 9.”

Funding

New ventures are different from the relatively simple assessment of new products, as there is often no marketable product available before or shortly after formation. Therefore, initial funding of the venture cannot normally be based on cash flow derived from early sales. The precise cash-flow profile will be determined by a number of factors, including development time and cost and the volume and profit margin of sales. Different development and sales strategies exist, but to some extent these factors are determined by the nature of the technology and markets (Figure 12.3(a)–(c)).

FIGURE 12.3 Cash flow profiles for three types of technology-based ventures: (a) research-based, e.g., biotechnology; (b) development-based, e.g., electronics; (c) production-based, e.g., software.

For example, biotechnology ventures typically require more start-up capital than electronics or software-based ventures and have longer product development lead times. Therefore, from the perspective of a potential entrepreneur, the ideal strategy would be to conduct as much development work as possible within the incubator organization before starting the new venture. However, there are practical problems with this strategy, in particular ownership of the intellectual property on which the venture is to be based.

Research in the United States suggests that the initial capital needed to start an NTBF is relatively modest, but both the amount and source of initial funding for the formation of an NTBF vary considerably. For example, software-based ventures typically require less start-up capital than either electronics or biotechnology ventures, and it is more common for such firms to rely solely on personal funding. Biotechnology firms tend to have the highest R&D costs, and consequently most require some external funding. In contrast, software firms typically require little R&D investment and are less likely to seek external funds. Case Study 12.2 reviews an example of competitive micro-finance for early-stage venture. The UK study found that almost three-quarters of the software firms were funded by profits after 3 years, whereas only a third of the biotechnology firms had achieved this.

The initial funding to establish an NTBF is rarely a major problem. However, Peter Drucker suggests an NTBF requires financial restructuring every 3 years [4]. Other studies identify stages of development, each having different financial requirements:

- Initial financing for launch.

- Second-round financing for initial development and growth.

- Third-round financing for consolidation and growth.

- Maturity or exit.

In general, professional financial bodies are not interested in initial funding because of the high risk and low sums of money involved. It is simply not worth their time and effort to evaluate and monitor such ventures. However, as the sums involved are relatively small – typically of the order of tens of thousands of pounds – personal savings, remortgages, and loans from friends and relatives are often sufficient. In contrast, third-round finance for consolidation is relatively easy to obtain, because by that time the venture has a proven track record on which to base the business plan, and the venture capitalist can see an exit route.

Given their strong desire for independence, most entrepreneurs seek to avoid external funding for their ventures. However, in practice, this is not always possible, particularly in the latter growth stages. The initial funding required to form an NTBF includes the purchase of accommodation, equipment, and other start-up costs, plus the day-to-day running costs such as salaries, utilities, and so on. Research in the United States and United Kingdom suggests that most NTBFs begin life as part-time ventures and are funded by personal savings, loans from friends and relatives, and bank loans, in that order. Around half also receive some funding from government sources, but in contrast receive next to nothing from venture capitalists. Venture capital is typically only made available at later stages to fund growth on the basis of a proven development and sales record.

Venture capitalists are keen to provide funding for a venture with a proven track record and strong business plan, but in return will often require some equity or management involvement. Moreover, most venture capitalists are looking for a means to make capital gains after about five years. However, almost by definition technical entrepreneurs seek independence and control, and there is evidence that some will sacrifice growth to maintain control of their ventures. For the same reason, few entrepreneurs are prepared to “go public” to fund further growth. Thus, many entrepreneurs will choose to sell the business and create another NTBF. In fact, the typical technical entrepreneur establishes an average of three NTBFs. Therefore, the biggest funding problem for an NTBF is likely to be for the second-round financing to fund development and growth. This can be a time-consuming and frustrating process to convince venture capitalists to provide finance. The formal proposal is critical at this stage. Professional investors will assess the attractiveness of the venture in terms of the strengths and personalities of the founders, the formal business plan and the commercial and technical merits of the product, typically in that order. View 12.1 provides some insights into the role of venture capital.

Crowd-funding

Crowd-funding is a relatively recent potential source of resources. Typically, this is mediated by a web portal on which projects can be posted to attract investors, often multiple nonprofessional investors who have some interest in the focus of the project. One of the largest crowd-funding services is kickstarter.com. Since its launch in 2009, Kickstarter has mediated the funding of 64,000 projects with pledges of US$1 billion from 6.5 million investors. This suggests a mean investment of around $16,000 per project. The focus is on creative and media projects, rather than high-technology. Seedups.com is another example, but has a greater focus on technology start-ups. As a result, the sums raised are larger, in the range of $25,000–$500,000, and investors have 6 months to review and bid for a stake in projects.

Corporate Venture Funding

A survey of corporate funding of NTBFs in the United Kingdom found that around 15% of large companies had made investments in external new ventures, mainly in their own sector [5]. This funding is cyclical, reflecting the business environment, for example, in 1998, the number of major corporations funding external ventures was around 110, but by 2000 this had grown to 350 [6]. The typical investment (in 1997) was in excess of £500,000, and the investing companies preferred ventures requiring additional capital for expansion, rather than funds for start-up or early development. The most common problems encountered were agreement of the rate of return and details of corporate representation in the venture. The average period of investment was 5 to 7 years, and corporate investors typically demanded a rate of return of 20–30%, which compares favorably with professional venture capitalists required returns of around 75%.

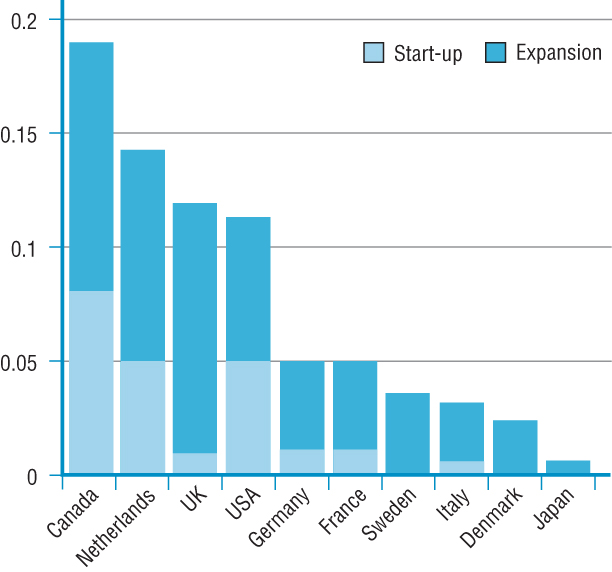

Regarding professional venture capitalists, Figure 12.4 highlights two important issues. First, that the availability of venture capital varies worldwide and that such disparities tend to be self-reinforcing as potential new ventures relocate to seek funding. The second point to note is the strong bias for finance for expansion, rather than start-ups, which is most significant in the United Kingdom. This creates a potential venture-funding gap, between the initial, usually self-financed stage, and the first involvement of professional venture capital. In the United Kingdom, this gap is in the region of £200,000 to £750,000 [7].

FIGURE 12.4 Venture capital as a percentage of GDP (1997).

Corporate investment in new ventures is increasingly popular in high-technology sectors, where large firms do not have access to all technologies in-house, and where emerging technologies remain unproven [8]. Investments in small biotechnology companies by pharmaceutical companies can be direct or indirect investment through specialist venture funds (see Case Study 12.3). Direct investment is preferred where there is a high probability of technological success, which is likely to impact the product pipeline in the near term. Indirect investments are concerned more with gaining windows on a range of early-stage technologies with the potential to impact the future direction of the product pipeline [9]. There has been a marked increase in the number of pharmaceutical companies investing through specialist venture funds, recent examples being Novartis (Novartis Ventures) and Bayer (Bayer Innovation). At the same time, pharmaceutical companies and their venture funds appear to be investing increasingly in independent seed capital funds focused on early-stage biotechnology, such as UK Medical Ventures (UK), New Medical Technologies (Switzerland), and Medical Technology Partners (USA). The precise objectives of such funds vary, but all share a common emphasis on strategic issues rather than purely financial. A principal investment criterion is “no fit, no deal,” the decision to invest being largely strategic, to “scout for ‘out there’ science.” The alternative mode of indirect venturing is participation in independent seed capital funds targeted at early-stage investments. A reason for investing is to access “deal flow” – that is, the opportunity to participate directly in subsequent rounds of funding beyond the seed capital stage. A similar strategy applies in other sectors, such as information and communications technology, as illustrated by Case Study 12.4. Clearly then, the goals of industry investments in new ventures are fundamentally different from those of professional venture capital firms. The goals of corporate venture funds are largely strategic, focusing on technology and potential new products, whereas the goals of venture capitalists are (rightly) purely financial.

Venture Capital

While there is general agreement about the main components of a good business plan, there are some significant differences in the relative weights attributed to each component. General venture capital firms typically only accept 5% of the technology ventures they are offered, and the specialist technology venture funds are even more selective, accepting around 3%. The main reasons for rejecting technology proposals compared to more general funding proposals are the lack of intellectual property, the skills of the management team, and size of the potential market. A survey of venture capitalists in North America, Europe, and Asia found major similarities in the criteria used, but also identified several interesting differences in the weights attached to some criteria. Case Study 12.4 provides further examples of venture capital funding. The criteria are similar to those discussed earlier, grouped into five categories:

- the entrepreneur’s personality

- the entrepreneur’s experience

- characteristics of the product

- characteristics of the market

- financial factors

Overall, venture capitalists require a proven ability to lead others and sustain effort; familiarity with the market; and the potential for a high return within 10 years. Case Study 12.5 provides an example of the challenges of early funding of technology-based ventures. The personality and experience of the entrepreneurs were consistently ranked as being more important than either product or market characteristics, or even financial considerations. However, there were a number of significant differences between the preferences of venture capitalists from different regions. Those from the United States placed greater emphasis on a high financial return and liquidity than their counterparts in Europe or Asia, but less emphasis on the existence of a prototype or proven market acceptance. Perhaps surprisingly, all venture capitalists are adverse to technological and market risks. Being described as a “high-technology” venture was rated very low in importance by the US venture capitalists, and the European and Asian venture capitalists rated this characteristic as having a negative influence on funding. Similarly, having the potential to create an entirely new market was considered a drawback.

A study of venture capitalists in the United Kingdom compared attitudes to funding technology ventures over a 10-year period and found that investment in technology-based firms as a percentage of total venture capital had increased from around 11% in 1990 to 25% by 2000 (by value) [10]. Of the total venture capital investment in UK NTBFs of £1.6 billion in the year 2000, 30% was for early-stage funding (by value, or 47% by number of firms), 47% for expansion (by value, or 47% by number of firms), and the rest for management buy-outs (MBO). This increase was due to a combination of the growth of specialist technology venture capitalists and greater interest by the more general venture capital firms. As venture capital firms have gained experience of this type of funding, and the opportunities for flotation have increased due to the new secondary financial markets in Europe such as the AIM, techMARK, and Neuer Markt, their returns on investment have increased significantly. In the 1980s returns to UK early-stage technology investments were under 10%, compared to venture capital norms of twice that, but by 2000 the returns of technology ventures increased to almost 25%, which is higher than all other types of venture investment. However, this recent growth in venture capital funding of NTBFs needs to be put into perspective. Although the United Kingdom has the most advanced venture capital community in Europe, venture capital still only accounts for between 1% and 3% of the external finance raised by small firms.

An important issue is the influence of venture capitalists on the success of NTBFs. They can play two distinct roles. The first, to identify or select those NTBFs that have the best potential for success – that is, “picking winners” or “scouting.” The second role is to help develop the chosen ventures, by providing management expertise and access to resources other than financial – that is, a “coaching” role. Distinguishing between the effects of these two roles is critical for both the management of and policy for NTBFs. For managers, it will influence the choice of venture capital firm; and for policy, the balance between funding and other forms of support. A study of almost 700 biotechnology firms over 10 years provides some insights to these different roles [11]. It found that when selecting start-ups to invest in, the most significant criteria used by venture capitalists were a broad, experienced top management team, a large number of recent patents and downstream industry alliances (but not upstream research alliances, which had a negative effect on selection). The strongest effect on the decision to fund was the first criterion, and the human capital in general. However, subsequent analysis of venture performance indicates that this factor has limited effect on performance and that the few significant effects are split equally between improving and impeding the performance of a venture. The effects of technology and alliances on subsequent performance are much more significant and positive.

In short, in the selection stage, venture capitalists place too much emphasis on human capital, specifically the top management team. In the development or coaching stages, venture capitalists do contribute to the success of the chosen ventures and tend to introduce external professional management much earlier than in NTBFs not funded by venture capital. Taken together, this suggests that the coaching role of venture capitalists is probably as important, if not more so, than the funding role, although policy interventions to promote NTBFs often focus on the latter.

Internal Corporate Venturing

The term corporate venturing or internal corporate venturing, sometimes confusingly referred to as “intrapreneurship,” to distinguish it from venturing that takes the form of investments in external business. If managed effectively, a corporate venture has the resources of a large organization and the entrepreneurial benefits of a small one. A corporate venture differs from conventional R&D and product development activities in its objectives and organization. The former seeks to exploit existing technological and market competencies, whereas the primary function of a new venture is to develop new competencies.

In practice, the distinction may be less clear. The Internet bubble of the late 1990s produced an ill-timed bandwagon for corporate venturing in large established companies in the information and communications technology sector as they attempted to capture some of the rapid growth of the dotcom start-up firms: in 1996, Nortel Networks created the Business Ventures Programme (see Case Study 12.6), in 1997 Lucent established the Lucent New Ventures Group, in 2000 Ericsson formed Ericsson Business Innovation and British Telecom formed Brightstar.

The most effective organization and management of a new venture will depend on two dimensions: the strategic importance of the venture for corporate development and its proximity to the core technologies and business [12]. Typically, top management has risen through the ranks of the organization, and therefore will be familiar with the evaluation of proposals related to the existing lines of business. However, by definition, new venture proposals are likely to require assessment of new technologies and/or markets. The following checklist can be used to assess the strategic importance of a new venture:

- Would the venture maintain our capacity to compete in new areas?

- Would it help create new defensible niches?

- Would it help identify where not to go?

- To what extent could it put the firm at risk?

- How and when could the firm exit from the venture?

Assessment of the second dimension, the proximity to existing skills and capabilities, is more difficult. On the one hand, a new venture may be driven by newly developed skills and capabilities, but on the other, a new venture may drive the development of new skills and capabilities. The former is consistent with an “incremental” strategy in which diversification is a consequence of evolution, the latter with a “rational” strategy which begins with the identification of new market opportunity. The relative merits and implications of these contrasting approaches were discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Whatever the primary motive for establishing a new venture, the proposal should identify potential opportunities for positive synergies across existing technologies, products, or markets. A checklist for assessing the proximity of the venture proposal to existing skills and capabilities would include:

- What are the key capabilities required for the venture?

- Where, how, and when is the firm going to acquire the capabilities, and at what cost?

- How will these new capabilities affect current capabilities?

- Where else could they be exploited?

- Who else might be able to do this, perhaps better?

Assessment of a new venture along these two dimensions will help determine the organization and management of the venture. In particular, the strategic importance will determine the degree of administrative control required, and the proximity to existing skills and capabilities will determine the degree of operational integration that is desirable. In general, the greater the strategic importance, the stronger the administrative linkages between the corporation and venture. Similarly, the closer the skills and capabilities are to the core activities, the greater the degree of operational integration necessary for reasons of efficiency. Putting the two dimensions together creates a number of different options for the organization and management of a new venture. In this section, we explore the design and management of internal corporate ventures, and in the next the role and management of joint ventures and alliances.

The management structures and processes necessary for routine operations are very different from those required to manage innovation. The pressures of corporate long-range strategic planning on the one hand, and the short-term financial control on the other, combine to produce a corporate environment that favors carefully planned and stable growth based on incremental developments of products and processes:

- Budgeting systems favor short-term returns on incremental improvements.

- Production favors efficiency rather than innovation.

- Sales and marketing are organized and rewarded on the basis of existing products and services.

Such an environment is unlikely to be conducive to radical innovation. An internal corporate venture attempts to exploit the resources of the large corporation, but provide an environment more conducive to radical innovation. The key factors that distinguish a potential new venture from the core business are risk, uncertainty, newness, and significance. However, it is not sufficient to promote entrepreneurial behavior within a large organization. Entrepreneurial behavior is not an end in itself, but must be directed and translated into desired business outcomes. Entrepreneurial behavior is not associated with superior organizational performance, unless it is combined with an appropriate strategy in a heterogeneous or uncertain environment [13]. This suggests the need for clear strategic objectives for corporate venturing and appropriate organizational structures and processes to achieve those objectives.

There are a wide range of motives for establishing corporate ventures [14]:

- Grow the business.

- Exploit underutilized resources.

- Introduce pressure on internal suppliers.

- Divest noncore activities.

- Satisfy managers’ ambitions.

- Spread the risk and cost of product development.

- Combat cyclical demands of mainstream activities.

- Learn about the process of venturing

- Diversify the business.

- Develop new technological or market competencies.

We will discuss each of these motives in turn and provide examples. The first three are primarily operational, the remainder primarily strategic.

To Grow the Business

The desire to achieve and maintain expected rates of growth is probably the most common reason for corporate venturing, particularly when the core businesses are maturing. Depending upon the time frame of the analysis, between only 5% and 13% of firms are able to maintain a rate of growth above the rate of growth in gross national product (GNP) [15]. However, the pressure to achieve this for publically listed firms is significant, as financial markets and investors expect the maintenance or improvement of rates of growth. The need to grow underlies many of the other motives for corporate venturing.

To Exploit Underutilized Resources in New Ways

This includes both technological and human resources. Typically, a company has two choices where existing resources are underutilized – either to divest and outsource the process or to generate additional contribution from external clients. However, if the company wants to retain direct and in-house control of the technology or personnel it can form an internal venture team to offer the service to external clients.

To Introduce Pressure on Internal Suppliers

This is a common motive, given the current fashion for outsourcing and market testing internal services. When a business activity is separated to introduce competitive pressure a choice has to be made – whether the business is to be subjected to the reality of commercial competition, or just to learn from it. If the corporate clients are able to go so far as to withdraw a contract, which is not conducive to learning, the business should be sold to allow it to compete for other work.

To Divest Noncore Activities

Much has been written of the benefits of strategic focus, “getting back to basics,” and creating the “lean” organization–rationalization, which prompts the divestment of those activities that can be outsourced. However, this process can threaten the skill diversity required for an ever-changing competitive environment. New ventures can provide a mechanism to release peripheral business activities, but to retain some management control and financial interest.

To Satisfy Managers’ Ambitions

As a business activity passes through its life cycle, it will require different management styles to bring out the maximum gain. This may mean that the management team responsible for a business area will need to change, whether between conception to growth, growth to maturity, or maturity to decline phases. A paradoxical situation often arises because of the changing requirements of a business area: top managers in place who are ambitious and want to see growth and managing businesses that are reaching the limits of that growth. To retain the commitment of such managers, the corporation will have to create new opportunities for change or expansion. These managers are not only potential facilitators for venture opportunities but also potential creators of venture opportunities. For example, Intel has long had a venture capital program that invests in related external new ventures, but in 1998, it established the New Business Initiative to bootstrap new businesses developed by its staff: “They saw that we were putting a lot of investment into external companies and said that we should be investing in our own ideas … our employees kept telling us they wanted to be more entrepreneurial.” The initiative invests only in ventures unrelated to the core microprocessor business, and in 1999 attracted more than 400 proposals, 24 of which were funded.

To Spread the Risk and Cost of Product Development

Two situations are possible in this case: (i) where the technology or expertise needs to be developed further before it can be applied to the mainstream business or sold to current external markets or (ii) where the volume sales on a product awaiting development must sell to a target greater than the existing customer groups to be financially justified. In both cases, the challenge is to understand how to venture outside current served markets. Too often, when the existing customer base is not ready for a product, the research unit will just continue its development and refinement process. If intermediary markets were exploited these could contribute to the financial costs of development, and to the maturing of the final product.

To Combat Cyclical Demands of Mainstream Activities

In response to the problem of cyclical demand Boeing set up two groups, Boeing Technology Services (BTS) and Boeing Associated Products (BAP), specifically with the function of keeping engineering and laboratory resources more fully employed when its own requirements waned between major development programmes. The remit for BTS was “to sell off excess engineering laboratory capacity without a detrimental impact on schedules or commitments to major Boeing product-line activities”; it has stuck carefully to this charter, and been careful to turn off such activity when the mainstream business requires the expertise. BAP was created to commercially exploit Boeing inventions that are usable beyond their application to products manufactured by Boeing. About 600 invention disclosures are submitted by employees each year, and these are reviewed in terms of their marketability and patentability. Licensing agreements are used to exploit these inventions; 259 agreements were made. Beyond the financial benefits to the company and to the employees of this program, it is seen to foster the innovation spirit within the organization.

To Learn About the Process of Venturing

Venturing is a high-risk activity because of the level of uncertainty attached, and we cannot expect to understand the management process as we do for the mainstream business. If a learning exercise is to be undertaken, and a particular activity is to be chosen for this process, it is critical that goals and objectives are set, including a review schedule. This is important not just for the maximum benefit to be extracted but for the individuals who will pioneer that venture. For example, NEES Energy, a subsidiary of New England Electric Systems Inc., was set up to bring financial benefits, but was also expected to provide a laboratory to help the parent company learn about starting new ventures [16].

Many companies develop hobby-size business activities to provide this “learning by doing,” but seldom is a time limit set on this learning stage, and as a consequence, no decision is formally made for the venture activities to be considered “proper businesses.” The implications of this practice are to drain the enterprising managers of their enthusiasm and erode the value of potential opportunities.

To Diversify the Business

While the discussion so far has implied that business development would be on a relatively small scale, this need not be the case. Corporate ventures are often formed in an effort to create new businesses in a corporate context, and therefore represent an attempt to grow via diversification. Therefore, a decline in the popularity of internal ventures is associated with an emphasis on greater corporate focus and greater efficiency. For example, the identification and reengineering of existing business processes became fashionable in the mid-1990s, but as firms have begun to exhaust the benefits of this approach they are now exploring options for creating new businesses. Such diversification may be vertical, that is, downstream or upstream of the current process in order to capture a greater proportion of the value added; or horizontal, that is by exploiting existing competencies across additional product markets.

To Develop New Competencies

Growth and diversification are generally based on the exploitation of existing competencies in new products markets, but a corporate venture can also be used as an opportunity for learning new competencies [17].

An organization can acquire knowledge by experimentation, which is a central feature of formal R&D and market research activities. However, different functions and divisions within a firm will develop particular frames of reference and filters based on their experience and responsibilities, and these will affect how they interpret information. Greater organizational learning occurs when more varied interpretations are made, and a corporate venture can better perform this function as it is not confined to the needs of existing technologies or markets.

Similarly, a corporate venture can act as a broker or clearing house for the distribution of information within the firm. In practice, large organizations often do not know what they know. Many firms now have databases and groupware to help store, retrieve, and share information, but such systems are often confined to “hard” data. As a result, functional groups or business units with potentially synergistic information may not be aware of where such information could be applied. Organizational learning occurs when more of an organization’s components obtain new knowledge and recognize it as of potential use.

In practice, the primary motives for establishing a corporate venture are strategic: to meet strategic goals and long-term growth in the face of maturity in existing markets (see Table 12.1). However, personnel issues are also important. Sectorial and national differences exist. In the United States, new ventures are also used to stimulate and develop entrepreneurial management, and in Japan, they help provide employment opportunities for managers and staff relocated from the core businesses (see Table 12.2). Nonetheless, the primary objectives are strategic and long term, and therefore warrant significant management effort and investment. Research Note 12.2 identifies four approaches to supporting corporate venturing.

TABLE 12.1 Objectives of Corporate Venturing in the United Kingdom

Source: Withers Solicitors, Window on technology: Corporate venturing in practice. 1997, London: Withers.

| Objective | Mean Rank* |

| 1. Long-term growth | 4.58 |

| 2. Diversification | 3.50 |

| 3. Promote entrepreneurial behavior | 2.68 |

| 4. Exploit in-house R&D | 2.23 |

| 5. Short-term financial returns | 2.08 |

| 6. Reduce/spread cost of R&D | 1.81 |

| 7. Survival | 1.76 |

(n = 90). * Scale: 1 = minimum, 5 = maximum importance.

TABLE 12.2 Comparison of Motives for Corporate Venturing in the United States and Japan

Source: Block, Z. and I. MacMillan, Corporate venturing: Creating new businesses within the firm, 1993. Boston: NIA. Copyright © 1993 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College: all rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business School Press.

| US Firms (n = 43) |

Japanese Firms (n = 149) |

|

| To meet strategic goals | 76 | 73 |

| Maturity of the base business | 70 | 57 |

| To provide challenges to managers* | 46 | 15 |

| To survive | 35 | 28 |

| To develop future managers* | 30 | 17 |

| To provide employment* | 3 | 24 |

*Denotes statistically significant difference.

12.3 Managing Corporate Ventures

A corporate venture is rarely the result of a spontaneous act or serendipity. Corporate venturing is a process that has to be managed. The management challenge is to create an environment that encourages and supports entrepreneurship and to identify and support potential entrepreneurs. In essence, the venturing process is simple and consists of identifying an opportunity for a new venture, evaluating that opportunity and subsequently providing adequate resources to support the new venture. There are six distinct stages divided between definition and development [18].

Definition stages

- Establish an environment that encourages the generation of new ideas and the identification of new opportunities and establish a process for managing entrepreneurial activity.

- Select and evaluate opportunities for new ventures and select managers to implement the venturing program.

- Develop a business plan for the new venture, decide the best location, and organization of the venture and begin operations.

- Development stages.

- Monitor the development of the venture and venturing process.

- Champion the new venture as it grows and becomes institutionalized within the corporation.

- Learn from experience in order to improve the overall venturing process.

Creating an environment that is conducive to entrepreneurial activity, is the most important, but most difficult stage. Superficial approaches to creating an entrepreneurial culture can be counterproductive. Instead, venturing should be the responsibility of the entire corporation, and top management should demonstrate long-term commitment to venturing by making available sufficient resources and implementing the appropriate processes.

The conceptualization stage consists of the generation of new ideas and identification of opportunities that might form the basis of a new business venture. The interface between R&D and marketing is critical during the conceptualization stage, but the scope of new venture conceptualization is much broader than the conventional activities of the R&D or marketing functions, which understandably are constrained by the needs of existing businesses. At this stage three basic options exist:

- Rely on R&D personnel to identify new business opportunities based on their technological developments, that is, essentially a “technology-push” approach.

- Rely on marketing managers to identify opportunities and direct the R&D staff into the appropriate development work, essentially a “market-pull” approach.

- Encourage marketing and R&D personnel to work together to identify opportunities.

The technology-push approach has been described as being “first-generation R&D,” the “market-pull” strategy as “second generation,” and the close coupling “third generation,” the implication being that firms should progress to close coupling [19]. The issue of strategic positioning was discussed in detail in Chapter 4. In theory, the third option is most desirable as it should encourage the coupling of technological possibilities and market opportunities at the concept stage, before substantial resources are committed to evaluation and development. However, in practice, technology push appears to be the dominant strategy. This is because at the conceptualization stage highly specialized technical knowledge is required about what is feasible and what is not, and therefore what the characteristics of the final product are likely to be. Nevertheless, R&D personnel may become locked into a specific technical solution or address the needs of atypical users. Therefore, management must ensure that R&D personnel are sufficiently flexible to modify or drop their proposals should technical issues or market requirements dictate.

Peter Drucker identifies a number of sources of ideas and opportunities and argues that the search process should be systematic rather than relying on serendipity [4]. He suggests seven common sources of opportunities that should be monitored on a routine basis:

- demographic changes

- new knowledge

- incongruities (i.e., gaps between expectations and reality)

- changes in industry or market structure

- unexpected successes or failures

- process needs

- changes in perception

Other sources of ideas include trade shows, exhibitions, and trade journals. In the specific case of new business ventures, there are four primary sources of ideas:

- the “bright idea”

- customers’ requests for a new product or service

- internal analysis of a company’s competencies and business processes

- scanning of external opportunities in related technologies, markets, or services

Contrary to popular perceptions, the “bright idea” is the least common and most risky source of new business ventures, because the other sources are more directly stimulated by a market need, technological expertise, or both together. These can be the initiative of either someone at operational or managerial level; the former may have difficulties finding an effective champion, whereas the latter may be too powerful, having the influence to force through an idea before it is exhaustively tested. A balance needs to be achieved between screening and championing the proposal. In contrast, a business venture based on a customer request has the highest chance of success as a potential market is to some extent predetermined. However, such ventures are typically based on an adaptation or extension of an existing product or service, and therefore less likely to spawn radical new businesses. These tend to be bottom-up initiatives, and the most difficult problem is to decide how the potential new business relates to the existing business or division. By far, the two most promising corporate ventures are the result of systematic scanning of the internal and external environments, a process we advocate in Chapter 2.

Venture capital firms can help firms to monitor the external environment without distraction and to take equity stakes in potential partners fairly anonymously. This practice is common in the pharmaceutical industry, where firms use a range of strategies to tap into the knowledge of biotechnology firms, including direct investment, licensing deals, and indirect investment through professionally managed venture funds. Direct investments are favoured for technologies of high strategic importance, licensing for process and product developments, and indirect investments for windows on emerging technologies [9].

Having identified the potential for a new venture, a product champion must convince higher management that the business opportunity is both technically feasible and commercially attractive, and therefore justifies development and investment. Potential corporate entrepreneurs face significant political barriers:

- They must establish their legitimacy within the firm by convincing others of the importance and viability of the venture.

- They are likely to be short of resources, but will have to compete internally against established and powerful departments and managers.

- They are, as advocates of change and innovation, likely to face at best organizational indifference, and at worst hostile attacks.

To overcome these barriers, a potential venture manager must have political and social skills, in addition to a viable business plan. In addition, the product champion must be able to work effectively in a nonprogrammed and unpredictable environment. This contrasts with much of the R&D conducted in the operating divisions, which is likely to be much more sequential and systematic. Therefore, a product champion requires dedication, flexibility, and luck to manage the transition from product concept to corporate venture, in addition to sound technical and market knowledge. The product champion is likely to require a complementary organizational champion, who is able to relate the potential venture to the strategy and structure of the corporation. A number of key roles must be filled when a new venture is established [20]:

- The technical innovator, who was responsible for the main technological development.

- The business innovator or venture manager, who is responsible for the overall progress of the venture.

- The product champion, who promotes the venture through the early critical stages.

- The executive champion or organizational champion, who acts as a protector and buffer between the corporation and venture.

- A high-level executive responsible for evaluating, monitoring, and authorizing resources for the venture, but not the operation of specific ventures.

A new venture requires two types of skill: the technical knowledge necessary to develop the product, process, or knowledge base; and the management expertise necessary to communicate and sell to the markets and parent organization (see Table 12.3). The dilemma that has to be resolved in each case is whether to allow and develop technical experts to play a role in selling the product or managing the business or to place managers above their heads to take the baton on.

TABLE 12.3 Systematic Differences Between Technical and Commercial Orientations

| R&D Personnel | Marketing Personnel | |

| Work Environment | ||

| Structure | Well defined | Ill defined |

| Methods | Scientific and codified | Ad hoc and intuitive |

| Data | Systematic and objective | Unsystematic and subjective |

| Pressures | Internal: How long will it take? | External: How long do we have? |

| Professional Orientation | ||

| Assumptions | Serendipity | Planning |

| Goals | New ideas: Can it be improved? | Big ideas: Does it work? |

| Performance criteria | Technical quality | Commercial value |

| Education and experience | Deep and focused | Broad |

To take project managers to venture manager status is often dangerous. While these individuals understand the product fully, they may have difficulties in maximizing the cost/price differential, perhaps not always realizing the commercial value of the product and being less experienced in the negotiation process. It can be equally difficult to identify a manager who can communicate the product characteristics to customers with real needs, relay those needs to the product development team, and communicate and justify venture management needs to the corporate center. View 12.2 discusses the challenges of managing internal corporate ventures.

12.4 Assessing New Ventures

The most appropriate filter to apply to a potential venture will depend on the motive for venturing. Roberts illustrates the point:

“The best time to detect if a CEO has a strategy or not is to observe the management team at work when trying to evaluate opportunities, especially those somewhat remote from the current business. On these occasions, we noticed that when faced with unfamiliar opportunities, management would put them through a hierarchy of different filters. The ultimate filter was always a fit between the products, customers, and markets that the opportunity brought and one key element, or driving force, of the business. This is a clear signal that management had a sound filter for its decision [21].”

In assessing any venture, it is essential to specify the purpose and criteria for success in the new market, business or technology. Ultimately the style of assessment adopted will depend on the size of the potential venture, the abilities of the people who currently understand the product and whether new partners or managers are expected to be introduced following assessment. See Case Study 12.7 for a description of how Lucent Technologies approached this. A plan needs to be written by the managers involved in the venture, in part to test whether they understand the business as well as the technology. It is essential for in-house managers to be fully involved in the market research. The use of market research consultants should be limited to providing a first pass of potential markets. No one can know the product better, especially if it is new, and has niche applications, than the people who have worked on its development, and whose future careers may depend on it.

The purpose and nature of a business plan for a new venture differ from that for established businesses. The main purpose of the venture plan is to establish if and how to conduct the new business and to attract key personnel and resources. The purpose of a plan for an existing business is to monitor and control performance. The technical and commercial aspects of a new venture plan will have much greater uncertainty than that for existing businesses. There are 10 essential elements of a new venture plan (see Table 12.4). The main criteria for assessing the business plan for a corporate venture are strategic fit and potential to enhance competitive position. But beyond such basic requirements, there appear to be significant differences between the criteria applied by American and Japanese firms (see Table 12.5).

TABLE 12.4 Components of a Typical Business Plan for a New Venture

| 1. Description of the proposed business, including its objectives and characteristics |

| 2. Strategic relationship between the new business and the parent firm |

| 3. The target markets, including size, trends, reasons for purchase, and specific target customers |

| 4. Assessment of the present and anticipated competition |

| 5. Human, physical, and financial resources required |

| 6. Financial projections, including assumptions and sensitivity analysis |

| 7. Well-defined milestones and go/no-go conditions |

| 8. Principal risks and how they will be managed |

| 9. Definition of failure and conditions under which the venture should be terminated |

| 10. Description of the venture’s management and compensation required |

TABLE 12.5 Criteria for Selecting Corporate Ventures

Source: Block, Z. and I. MacMillan, Corporate venturing: Creating new businesses within the firm. 1993. Boston: NIA. Copyright © 1993 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College: all rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business School Press.

| USA (n = 39) | Japan (n = 126) | |

| Strategic fit | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| Competitive advantage | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| Potential return on investment* | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| Existence of market* | 3.9 | 4.4 |

| Potential sales | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Risk/reward ratio | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| Presence of product champion | 3.6 | 4.0 |

| Synergy | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| Opportunity to create new market* | 3.1 | 3.8 |

| Closeness to present technology* | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| Patentability* | 2.3 | 2.9 |

1 = unimportant, 5 = critical. *Denotes statistically significant difference.

Structures for Corporate Ventures

The choice of location and structure for a new venture will depend on a number of factors. The most fundamental factor is how close the activities are to the core business. How close a venture’s focal activity is to the parent firm’s technology, products and markets will determine the learning challenges the venture will face and the most appropriate linkages with the parent. In practice, there is likely to be some trade-off between the desire to optimize learning and the desire to optimize the use of existing resources. The venture will need to acquire resources, know-how and information from the corporate parent, get sufficient attention and commitment, but at the same time be protected politically and allowed optimal access to the target market. Consideration of these sometimes conflicting requirements will determine the best location and structure for the venture.

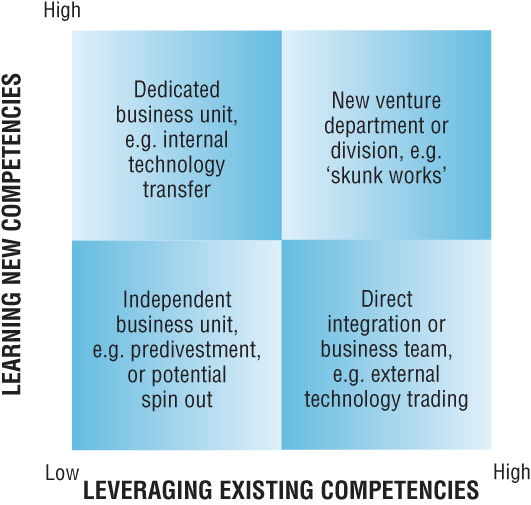

The classic study by Burgelman and Sayles of six internal ventures within a large American corporation demonstrated the managerial and administrative difficulties of establishing and managing internal ventures [22]. The study confirmed that no single organizational solution is optimal, and that different structures and processes are required in different circumstances. The choice of structure will depend on the level and urgency of the venturing activity, the nature and number of ventures to be established, and the corporate culture and experience. More fundamentally, it will depend on the balance between the desire to learn new competencies and the need to leverage existing competencies, as shown in Figure 12.5. For example, in e-business established firms are faced with the decision whether to develop separate businesses to exploit the opportunities, or to fully integrate e-business with the existing business. Neither strategy nor structure appears to be inherently superior and depends on a consideration of the relatedness of the assets, operations, management, and brand [23]. Design options for corporate ventures include:

- direct integration with existing business

- integrated business teams

- a dedicated staff function to support efforts company-wide

- a separate corporate venturing unit, department or division

- divestment and spin-off

FIGURE 12.5 The most effective structure for a corporate venture depends on the balance between leverage or learning (exploit versus explore).

Source: Tidd, J. and S. Taurins, Learn or leverage? Strategic diversification and organisational learning through corporate ventures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 1999. 8(2), 122–9.

Each structure will demand different methods of monitoring and management – that is, procedures, reporting mechanisms, and accountability. These choices are illustrated by studies of venturing in the Europe and the United States [24].

Direct Integration

Direct integration as an additional business activity is the preferred choice where radical changes in product or process design are likely to impact immediately on the mainstream operations and if the people involved in that activity are inextricably involved in day-to-day operations. For example, many engineering-based companies have introduced consultancy to their business portfolio, and in other technical organizations with large laboratory facilities these too have been sold out for analysis of samples, testing of materials, and so on. In such cases, it is not possible to outsource such activities because the same personnel and equipment are required for the core business.

Integrated Business Teams

Integrated business teams are most appropriate where the expertise will have been nurtured within the mainstream operations, and may support or require support from those operations for development. Strategically, the product is sufficiently related to the mainstream business’s key technologies or expertise that the center wishes to retain some control. This control may either be to protect the knowledge that is intrinsic in the activity or to ensure a flow-back of future development knowledge. A business team of secondees is established to coordinate sourcing of both internal and external clients, and is usually treated as a separate accounting entity in order to ease any subsequent transition to a special business unit.

New Ventures Department

A new ventures department is a group separate from normal line management that facilitates external trading. It is most suitable when projects are likely to emerge from the operational business on a fairly frequent basis and when the proposed activities may be beyond current markets or the type of product package sold is different. This is the most natural way for the trading of existing expertise to be developed when it lies fragmented through the organization, and each source is likely to attract a different type of customer. The group has responsibility for marketing, contracting, and negotiation, but technical negotiation and supply of services take place at operational level.

New Venture Division

A new venture division provides a safe haven where a number of projects emerge throughout the organization and allows separate administrative supervision. Strategically, top management can retain a certain level of control until greater clarity on each venture’s strategic importance is understood, but the efficiency of the mainstream business needs to be maintained without distraction, so some autonomy is required. Operational links are loose enough to allow information and know-how to be exchanged with the corporate environment. The origins of such a division vary:

- An effort to bring existing technologies and expertise throughout the company together for adaptation to new or existing markets.

- To combine research from different fields or locations to accelerate the development of new products.

- To purchase or acquire expertise currently outside of the business for application to internal operations, or to assist new developments.

- To examine new market areas as potential targets for existing or adapted products within the current portfolio.

Where a critical mass of projects exists, a separate new venture division allows greater focus on the external environment, and the distance from the core corporation facilitates a global and cross-divisional view to be taken. Unfortunately, the division can often become a kind of dustbin for every new opportunity, and therefore it is critical to define the limits of its operation and its mission, in particular, the criteria for termination or continued support of specific projects.

Special Business Units

Special dedicated new business units are wholly owned by the corporation. High strategic relevance requires strong administrative control. Businesses like this tend to come about because the activity is felt to have enough potential to stand alone as a profit center and can thus be assessed and operated as a separate business entity. The requirement is that key people can be identified and extracted from their mainstream operational role.

For the business to succeed under the total ownership and control of a large corporate, it must be capable of producing significant revenue streams in the medium term. On average, the critical mass appears to be around 12% of total corporate turnover, but in some cases, the threshold for a separate unit is much higher. A potential new business must not only be judged on its relative size or profitability but also more importantly, by its ability to sustain its own development costs. For example, a profitable subsidiary may never achieve the status of a separate new business if it cannot support its own product development.

However, physically separating a business activity does not ensure autonomy. The greatest impediment to such a unit competing effectively in the market is a cosy corporate mentality. If managers of a new business are under the impression that the corporate parent will always assist, provide business and second its expertise and services at non-market rates, that business may never be able to survive commercial pressures. Conversely, if the parent plans to retain total ownership, the parent cannot realistically treat that unit independently.

Independent Business Units

Differing degrees of ownership will determine the administrative control over independent business units, ranging from subsidiary to minority interest. Control would only be exercised through a board presence if that were held. There are two reasons for establishing an independent business as opposed to divisionalizing an activity: to focus on the core business by removing the managerial and technical burden of activities unrelated to the mainstream business; or to facilitate learning from external sources in the case of enabling technologies or activities. This structure has benefits for both parent and venture:

- Defrayed risk for parent, greater freedom for venture.

- Less supervisory requirement for parent, less interference for venture.

- Reduced management distraction for parent, and greater focus for venture.

- Continued share of financial returns for parent, greater commitment from managers of the venture.

- Potential for flow-back or process improvements or product developments for parent, and learning for the venture.

The assignment of technical personnel is one of the most difficult problems when establishing an independent business unit. If the individuals necessary to coordinate future product development are unwilling to leave the relative security and comfort of a large corporate facility, which is understandable, the new business may be stopped in its tracks. It is critical to identify the most desirable individuals for such an operation, assessed in terms of their technical ability and personal characteristics. It is also important to assess the effect of these individuals leaving the mainstream development operations, as the capability of the parent’s operations could be easily damaged.

Nurtured Divestment

Nurtured divestment is appropriate where an activity is not critical to the mainstream business. The product or service has most likely evolved from the mainstream, and while supporting these operations, it is not essential for strategic control. The design option provides a way for the corporate to release responsibility for a particular business area. External markets may be built up prior to separation, giving time to identify which employees should be retained by the corporate and providing a period of acclimatization for the venture. The parent may or may not retain some ownership.

Complete Spin-off

No ownership is retained by the parent corporation in the case of a complete spin-off. This is essentially a divest option, where the corporation wants to pass over total responsibility for activity, commercially and administratively. This may be due to strategic unrelatedness or strategic redundancy, as a consequence of changing corporate strategic focus. A complete spin-off allows the parent to realize the hidden value of the venture and allows senior management of the parent to focus on their main business. We discuss these in greater detail in Section 12.3.

In addition to having the most appropriate structure for corporate venturing, Tushman and O’Reilly identify three other organizational aspects that have to be managed to achieve what they call the “ambidextrous” organization – the coexistence of young, entrepreneurial, risky ventures with the more established, proven operations [25]:

- Articulating a clear, emotionally engaging, and consistent vision This helps to provide a strategic anchor for the diverse demands of the mainstream and venture businesses.

- Building a senior team with diverse competencies The composition and demography of the senior team are critical. Homogeneity typically results in greater consensus, faster decision making, and easier execution, but lowers levels of creativity and innovation; whereas heterogeneity can cause conflicts, but promotes more diverse perspectives. To achieve a balance, they suggest homogeneity by tenure/length of service, but diversity in backgrounds and perspectives. Alternatively, senior teams can be relatively homogeneous, but have more diverse middle management teams reporting to them.

- Developing healthy team processes The need for creativity needs to be balanced with the need for execution, and team members must be able to resolve conflicts and to collaborate.

However, there is disagreement in the research regarding the influences of the degree of integration of corporate ventures and the effects on their subsequent success. A study of almost 100 corporate ventures in Canada provided strong support for the need for high levels of integration between the corporate parent and the ventures. It found that the success of a venture was associated with a strong relationship with the corporate parent – specifically use of the parent firm’s systems and resources – and conversely that the autonomy of ventures was associated with lower performance of the venture [26]. This appears to contradict the more general body of research which suggests that the managerial independence of ventures is associated with success. For example, a study of spin-offs from Xerox found that those ventures with high levels of funding and senior management from the parent were less successful than those funded more by professional venture capitalists and outside management [27]. One reason for this disagreement might be the period of assessment and measures of success: the Canadian study used the achievement of milestones as the measure of success, and the average age of the new ventures was less than 5 years; the Xerox study used two measures of success, average rates of growth and financial market value of the ventures, and assessed these over 20 years. In any case, this reflects the real difficulty of getting the right balance between autonomy and integration, as one study found:

Internal entrepreneurs are faced with two choices: either go underground or spin-off a new venture, with or without the blessing of the parent company … it is therefore advisable to spin-off a company in agreement with the parent that contributes technology, personnel and possibly cash, in exchange for minority equity participation. The parent can hold one or more seats on the board of directors, provide advice, networking, and marketing support, share its R&D and pilot production facilities, and so on, but must refrain from interfering with management … continued cooperation with the parent also carries a price … with a seat on the board the parent is able to monitor and influence the evolution of the technology, and more importantly of the market [28]. (emphasis added)

This is critical as the Xerox study found that the eventual successful business models developed by the spin-offs evolved substantially from the initial plans at formation were very different to the business models of the parent company and involved significant experimentation to explore the technologies and markets.

Learning Through Internal Ventures

The success of corporate venturing varies enormously between firms, but on average around half of all new ventures survive to become operating divisions, which suggests that venturing may be a less risky strategy for diversification than acquisition or merger. Typically, a venture will achieve profitability within 2 to 3 years, and almost half are profitable within 6 years. However, the profitability of the overall corporate venturing process may be lower due to the effect of a few large failures. Four factors appear to characterize firms that are consistently successful at corporate venturing:

- Distinguish between bad decisions and bad luck when assessing failed ventures.

- Measure a venture’s progress against agreed milestones, and if necessary redirect.

- Terminate a venture when necessary, rather than make further investments.

- View venturing as a learning process and learn from failures as well as successes.

There are two main causes of failure of internal ventures: strategic reversal and the emergence trap. Strategic reversal occurs because of a conflict between the timescales of the new venture and the parent organization. An internal venture may be set up for a number of reasons: to support a strategy of diversification; because of a risk-taking top management; an excess of corporate cash; or a decline in the firm’s main line of business. Whatever the reasons, the internal or external environment is unlikely to remain stable for the life of the new venture. A change of climate can result in the premature termination of a venture. Even normal business cycles may affect the fortunes of a new venture. For example, there appears to be a strong correlation between changes in corporate profits and the number of new ventures set up [29].

The other, more subtle cause of venture failure is the emergence trap. As a venture expands, it may lead to internal territorial infringements, and success leads to jealousy and may result in attempts to undermine the venture. Differences between the culture and style of managers in the parent firm and new venture are likely to amplify these problems (see Table 12.6). In particular, new venture divisions are highly visible and represent a concentration of expenditure, and are therefore more vulnerable to changes in corporate performance or management sentiment.

TABLE 12.6 Potential Sources of Conflict Between Corporate and Venture Managers

| Corporate Management | New Venture Management |

| Modest uncertainty | Major technical and market uncertainties |

| Emphasis on detailed planning | Emphasis on opportunistic risk-taking |

| Negotiation and compromise | Autonomous behavior |

| Corporate interests and rules | Individualistic and ad hoc |

| Homogeneous culture and experience | Heterogeneous backgrounds |

In practice, there is a trade-off between rapid growth and learning. A new venture will not have an indefinite period in which to prove itself, and in most cases, corporate management will set high targets for growth and financial return in order to offset the risk and uncertainty inherent in a new venture. If successful, the venture will quickly achieve a track record and therefore attract further support from corporate management, resulting in a virtuous spiral of growth and investment. Conversely, if the venture fails to deliver early growth in sales or returns, it may be starved of further support, thus increasing the likelihood of subsequent failure, a vicious spiral of low investment and decline. There are a number of ways to help avoid these problems [30]:

- Make corporate and divisional managers aware of the long-term benefits of venture operations.

- Clearly specify the functions, procedures, boundaries, and rewards of venture management.

- Establish a limited number of ventures with independent budgets.

- Establish and maintain multiple sources of sponsorship for ventures.