Chapter 12

Financing

Tell me how you’re financed and I’ll tell you who you are

When you evaluate how a company is financed, you must perform both dynamic and static analyses.

- As we saw in the previous chapter, when it is founded, a company makes two types of investment. Firstly, it invests to acquire land, buildings, equipment, etc. Secondly, it makes operating investments, specifically start-up costs and building up working capital.

If the circle is a virtuous one, i.e. if the cash flows generated are enough to meet interest and dividend payments and repay debt, the company will gradually be able to grow and, as it repays its debt, it will be able to borrow more (the origin of the illusion that companies never repay their loans).

Conversely, the circle becomes a vicious one if the company’s resources are constantly tied up in new investments or if cash flow from operating activities is chronically low. The company systematically needs to borrow to finance capital expenditure, and it may never be able to pay off its debt, not to mention pay dividends.

Evaluating these matters is the dynamic approach.

- In parallel with the dynamic approach, you must look at the current state of the company’s finances with two questions in mind:

- Given the proportion of the company’s assets financed by bank and other financial debt and the free cash flow generated by the company, can the company repay its debt?

- Given the term structure of the company’s debt, is the company running a high risk of illiquidity?

This is the static approach.

Section 12.1 A dynamic analysis of the company’s financing

To perform this analysis you will rely on the cash flow statement.

1. The fundamental concept of cash flow from operating activities

The cash flow statement (see Chapter 5) is designed to separate operating activities from investing and financing activities. Accordingly, it shows cash flows from operating and investing activities and investments on the one hand, and from financing activities on the other. This breakdown will be very useful to you when valuing the company and examining investment decisions.

The concept of cash flow from operating activities, as shown by the cash flow statement, is of the utmost importance. It depends on three fundamental parameters:

- the rate of growth in the company’s business;

- the amount and nature of operating margins;

- the amount and nature of working capital.

An analysis of the cash flow statement is therefore the logical extension of the analysis of the company’s margins and the changes in working capital.

Analysing the cash flow statement means analysing the profitability of the company from the point of view of its operating dynamics, rather than the value of its assets.

We once analysed a fast-growing company with high working capital. Its cash flow from operating activities was insufficient, but its inventories increased in value every year. We found that the company was turning a handsome net income, but its return on capital employed was poor, as most of its profit was made on capital gains on the value of its inventories. Because of this, the company was very vulnerable to any recession in its sector.

In this case, we analysed the cash flow statement and were able to show that the company’s trade activity was not profitable and that the capital gains just barely covered its operating losses. It also became apparent that the company’s growth process led to huge borrowings, making the company even more vulnerable in the event of a recession.

2. Free cash flow after interest

Free cash flow after interest is equal to cash flows from operating activities minus cash flows from investments (capex net of disposal of fixed assets). It therefore includes the investment policy of the firm.

Free cash flow after interest measures, if negative, the financial resources that the company will have to find externally (from its shareholders or lenders) to meet the needs for cash generated by its operating and investment activities. If positive, the firm will be able to reduce its debt, to pay dividends without having to raise debt or even to accumulate cash for future needs. Free cash flow after interest will therefore set the tune for the financing policy.

3. How is the company financed?

As an analyst, you must understand how the company finances its activities over the period in question. New equity capital? New debt? Reinvesting cash flow from operating activities? Asset disposals can contribute additional financial resources.

You should focus on three items for this analysis: equity capital issues, debt policy and dividend policy.

- Financing through new equity issuance: did the firm call for new equity from its shareholders during the period and, if yes, what was it used for (to reduce debt, to finance a new capex programme)? You can also come across the opposite situation whereby the company buys back part of its shares; this is a way of returning cash to shareholders.1 In this case, does the company want to alter its financial situation? Does it no longer have any investment opportunities?

- Financing through debt: analysing the net increase or decrease in the company’s debt burden is a question of financial structure:

- If the company is paying down debt, is it doing so in order to improve its financial structure? Has it run out of growth opportunities? Is it to pay back loans that were contracted when interest rates were high?

- If the company is increasing its debt burden, is it taking advantage of unutilised debt capacity? Or is it financing a huge investment project or reducing its shareholders’ equity and upsetting its financial equilibrium in the process?

- The dividend policy: as we will see in Chapter 37, the company’s dividend policy is also an important aspect of its financial policy. It is a valuable piece of information when evaluating the company’s strategy during periods of growth or recession:

- Is the company’s dividend policy consistent with its growth strategy?

- Is the company’s cash flow reinvestment policy in line with its capital expenditure programme?

You must compare the amount of dividends with the investments and cash flows from operating activities of the period.

In Section III of this book, we will examine the more complex reasoning processes that go into determining investment and financing strategies. For the moment, keep in mind that analysis of the financial statements alone can only result in elementary, common-sense rules.

As you will see later, we stand firmly against the following “principles”:

- The amount of capital expenditure must be limited to the cash flow from operating activities. No! After reading Section III you will understand that the company should continue to invest in new projects until their marginal profitability is equal to the required rate of return. If it invests less, it is underinvesting; if it invests more, it is overinvesting, even if it has the cash to do so.

- The company can achieve equilibrium by having the “cash cow” divisions finance the “glamour”2 divisions. No! With the development of financial markets, every division whose profitability is commensurate with its risk must be able to finance itself. A “cash cow” division should pay the cash flow it generates over to its providers of capital.

Studying the equilibrium between the company’s various cash flows in order to set rules is tantamount to considering the company a world unto itself. This approach is diametrically opposed to financial theory. It goes without saying, however, that you must determine the investment cycle that the company’s financing cycle can support. In particular, debt repayment ability remains paramount. We have already warned you about that in Chapter 2!

Section 12.2 A static analysis of the company’s financing

Focusing on a multi-year period, we have examined how the company’s margins, working capital and capital expenditure programmes determine its various cash flows. We can now turn our attention to the company’s absolute level of debt at a given point in time and to its capacity to meet its commitments while avoiding liquidity crises.

1. Can the company repay its debts?

The best way to answer this simple, fundamental question is to take the company’s business plan and project future cash flow statements. These statements will show you whether the company generates enough cash flow from operating activities such that after financing its capital expenditure, it has enough left over to meet its debt repayment obligations without asking shareholders to reach into their pockets. If the company must indeed solicit additional equity capital, you must evaluate the market’s appetite for such a capital increase. This will depend on who the current shareholders are. A company with a core shareholder will have an easier time than one whose shares are widely held, as this core shareholder, knowing the company well, may be in a position to underwrite the share issue. It will also depend on the value of equity capital (if it is near zero, maybe only a vulture fund3 will be interested).

Naturally, this assumes that you have access to the company’s business plan, or that you can construct your own from scenarios of business growth, margins, changes in working capital and likely levels of capital expenditure. We will take a closer look at this approach in Chapter 31.

Analysts and lending banks have, in the meantime, adopted a “quick-and-dirty” way to appreciate the company’s ability to repay its debt: the ratio of net debt to EBITDA. This is, in fact, the most often used financial covenant4 in debt contracts! This highly empirical measure is nonetheless considered useful, because EBITDA is very close to cash flow from operating activities, give or take changes in working capital, interest and income tax. A value of 2.5 is considered a critical level, below which the company should generally be able to meet its repayment obligations.

If we were to oversimplify, we would say that a value of 2.5 signifies that the debt could be repaid in 2.5 years provided the company halted all capital expenditure and didn’t pay corporate income tax during that period. Of course, no one would ask the company to pay off all its debt in the span of 2.5 years, but the idea is that it could if it had to.

Conversely, bank and other financial borrowings equal to more than 2.5 times EBITDA are considered a heavy debt load, and give rise to serious doubts about the company’s ability to meet its repayment commitments as scheduled. As we will see in Chapter 46, leveraged buyouts can engender this type of ratio. When the value of the ratio exceeds 5 or 6, the debt becomes “high-yield”, the politically correct term for “junk bonds”.

Naturally, these levels of ratios should be taken for what they are – indications and not absolute references.

Bankers are more willing to lend money to sectors with stable and highly predictable cash flows (food retail, utilities, real estate), even on the basis of a high net debt to EBITDA ratio, than to others where cash flows are more volatile (media, capital goods, electronics). Additionally, the lender will be sensitive to the effective capacity for generating cash flows. So, if past cash flow statements constantly show negative free cash flows after financial expense, the banks will be very reluctant to lend, even if EBITDA is comfortable.

Accordingly, when changes in working capital are not negligible compared with the amount of EBITDA, the net debt/EBITDA ratio loses its relevance.

The following table shows trends in the net debt/EBITDA ratio posted by various different sectors in Europe between 2000 and 2018e.

| Sector | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2016e | 2017e |

| Aerospace & Defence | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3% | 0.0% |

| Automotive | 0.7 | 0.3 | nm | nm | nm | nm |

| Building Materials | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.0% | 1.6% |

| Capital Goods | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.3% | 1.1% |

| Consumer Goods | 0.6 | 0.6 | nm | 0.2 | 0.1% | nm |

| Food Retail | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.8% | 1.6% |

| IT Services | nm | nm | nm | 0.9 | 0.5% | 0.1% |

| Luxury Goods | 3.0 | 1.1 | 0.3 | nm | nm | nm |

| Media | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1% | 0.9% |

| Mining | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 2.2% | 1.5% |

| Oil & Gas | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 2.1% | 1.6% |

| Pharmaceuticals | nm | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.1% | 0.9% |

| Steel | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 3.0% | 2.4% |

| Telecom Operators | 3.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.3% | 2.1% |

| Utilities | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.2% | 3.3% |

Source: Exane BNP Paribas

Food retail and utilities are among the most highly leveraged sectors. One explanation is their capital intensity, which is strong. Another is the willingness of lenders to lend money to these sectors as they own real-estate assets with a value independent of the business (a food store can be redeveloped into a textile shop) or with high long-term visibility on cash flows (concession contracts).

Similarly, analysts look at the interest coverage ratio, ICR (or debt service coverage or debt service ratio), i.e. the ratio of EBIT to net interest expense. A ratio of 3:1 is considered the critical level. Below this level, there are serious doubts as to the company’s ability to meet its obligations as scheduled, as was the case for the transport sector post 9/11. Above it, the company’s lenders can sleep more easily at night!

Rating agencies generally prefer to consider the ratio cash flow to net debt (they call our cash flow “funds from operations”, or FFO). It is true that cash flow is closer than EBITDA to the actual capacity of the firm to repay its debt.

Until around 20 years ago, the company’s ability to repay its loans was evaluated on the basis of its debt-to-equity ratio, or gearing, with a 1:1 ratio considered the critical point.

Certain companies can support bank and other financial debt in excess of shareholders’ equity, specifically companies that generate high operating cash flow. Eurotunnel, the company which operates the Channel Tunnel and generates robust cash flows, is an example. Conversely, other companies would be unable to support debt equivalent to more than 30% of their equity, because their margins are very thin. For example, the operating profit of Kuoni, the travel company, is at best only 3% of its sales revenue.

The debt-to-equity ratio is still computed by some analysts and used in some debt contracts. It is an unfortunate illustration of inertia of concepts in finance.

If you insist on using equity to compute debt ratios, it is better to use the ratio of net debt divided by the market value of equity. Equity is thus taken into account for what it is worth and not for a book amount, which is, most of the time, far from economic reality. Nevertheless, this ratio presents the drawback of being quite volatile.

2. Is the company running a risk of illiquidity?

To understand the notion of liquidity, look at the company in the following manner: at a given point in time, the balance sheet shows the company’s assets and commitments. This is what the company has done in the past. Without planning for liquidation, we nevertheless attempt to classify the assets and commitments based on how quickly they are transformed into cash. When will a particular commitment result in a cash disbursement? When will a particular asset translate into a cash receipt?

To meet its commitments, either the company has assets it can monetise or it must contract new loans. Of course, new loans only postpone the day of reckoning until the new repayment date. By that time, the company will have to find new resources.

Illiquidity comes about when the maturity of the assets is greater than that of the liabilities. Suppose you took out a loan, to be repaid in six months, to buy a machine with a useful life of three years. The useful life of the machine is out of step with the scheduled repayment of the loan and the interest expenses on it. Consequently, there is a risk of illiquidity, particularly if there is no market to resell the machine at a decent price and if the activity is not profitable. Similarly, at the current asset level, if you borrow three-month funds to finance inventories that turn over in more than three months, you are running the same risk.

An illiquid company is not necessarily required to declare bankruptcy, but it must find new resources to bridge the gap. In so doing, it forfeits some of its independence because it will be obliged to devote a portion of its new resources to past uses. In times of recession, it may have trouble doing so, and indeed be forced into bankruptcy.

Analysing liquidity means analysing the risk the company will have to “borrow from Peter to pay Paul”. For each maturity, you must compare the company’s cash needs with the resources it will have at its disposal.

We say that a balance sheet is liquid when, for each maturity, there are more assets being converted into cash (inventories sold, receivables paid, etc.) than there are liabilities coming due.

This graph shows, for each maturity, the cumulative amount of assets and liabilities coming due on or before that date.

Liquidity

If, for a given maturity, cumulative assets are less than cumulative liabilities, the company will be unable to meet its obligations unless it finds a new source of funds. The company shown in this graph is not in this situation.

What we are measuring is the company’s maturity mismatch, similar to that of a financial institution that borrows short-term funds to finance long-term assets.

However, in real life, things are often more complex than the situation represented by the smoothed curves of the above graph. For example, the graph for a company with large debts maturing in five years would look like this:

Liquidity bis

The company will have to manage its debt within a few years, or even restructure it (see Section 39.3).

(a) Liquidity ratios

To measure liquidity, then, we must compare the maturity of the company’s assets to that of its liabilities. This rule gives rise to the following liquidity ratios, commonly used in loan covenants. They enable banks to monitor the risk of their borrowers.

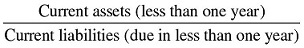

-

Current ratio:

This ratio measures whether the assets to be converted into cash in less than one year exceed the debts to be paid in less than one year.

The quick ratio is another measure of the company’s liquidity. It is the same as the current ratio, except that inventories are excluded from the calculation. Using the quick ratio is a way of recognising that a portion of inventories corresponds to the minimum the company requires for its ongoing activity. As such, they are tantamount to fixed assets. It also recognises that the company may not be able to liquidate the inventories it has on hand quickly enough in the event of an urgent cash need. Certain inventory items have value only to the extent they are used in the production process. The quick ratio (also called the acid test ratio) is calculated as follows:

A quick ratio below one means the company might have short-term liquidity problems as it owns less current assets than it owes to its short-term lenders. If the latter stop granting it payment facilities, it will need a cash injection from shareholders or long-term lenders or face bankruptcy.

Finally, the cash ratio completes the set:

The cash ratio is generally very low. Its fluctuations often do not lend themselves to easy interpretation.

(b) More on the current ratio

Traditional financial analysis relies on the following rule:

By maintaining a current ratio above one (more current assets than current liabilities), the company protects its creditors from uncertainties in the “gradual liquidation” of its current assets, namely in the sale of its inventories and the collection of its receivables. These uncertainties could otherwise prevent the company from honouring its obligations, such as paying its suppliers, servicing bank loans or paying taxes.

If we look at the long-term portion of the balance sheet, a current ratio above one means that sources of funds due in more than one year, which are considered to be stable,5 are greater than fixed assets, i.e. uses of funds “maturing” in more than one year. If the current ratio is below one, then fixed assets are being financed partially by short-term borrowings or by a negative working capital. This situation can be dangerous. These sources of funds are liabilities that will very shortly become due, whereas fixed assets “liquidate” only gradually in the long term.

The current ratio was the cornerstone of any financial analysis years ago. This was clearly excessive. The current ratio reflects the choice between short-term and long-term financing. In our view, this was a problem typical of the credit-based economy, as it existed in the 1970s in Continental Europe. Today, the choice is more between shareholders’ equity capital and banking or financial debt, whatever its maturity. That said, we still think it is unhealthy to finance a permanent working capital with very short-term resources. The company that does so will be defenceless in the event of a liquidity crisis, which could push it into bankruptcy.

(c) Financing working capital

To the extent that working capital represents a permanent need, logic dictates that permanent financing should finance it. Since it remains constant for a constant business volume, we are even tempted to say that it should be financed by shareholders’ equity. Indeed, companies with high working capital are often largely funded by shareholders’ equity. This is the case, for example, with big champagne companies, which often turn to the capital markets for equity funding.

Nevertheless, most companies would be in an unfavourable cash position if they had to finance their working capital strictly with long-term debt or shareholders’ equity. Instead, they use the mechanism of revolving credits, which we will discuss in Chapter 21. For that matter, the fact that the components of working capital are self-renewing encourages companies to use revolving credit facilities in which customer receivables and inventories often collateralise the borrowings.

By their nature, revolving credit facilities are always in effect, and their risk is often tied directly to underlying transactions or collateralised by them (bill discounting, factoring, securitisation, etc.).

Full and permanent use of short-term revolving credit facilities can often be dangerous, because it:

- exhausts borrowing capacity;

- inflates interest expense unnecessarily;

- increases the volume of relatively inflexible commitments, which will restrict the company’s ability to stabilise or restructure its activity.

Working capital is not only a question of financing. It can carry an operational risk as well. Short-term borrowing does not exempt the company from strategic analysis of how its operating needs will change over time. This is a prerequisite to any financing strategy.

Companies that export a high proportion of their sales or that participate in construction and public works projects are risky inasmuch as they often have insufficient shareholders’ equity compared with their total working capital. The difference is often financed by revolving credits, until one day, when the going gets rough . . .

In sum, you must pay attention to the true nature of working capital, and understand that a short-term loan that finances permanent working capital cannot be repaid by the operating cycle except by squeezing that cycle down, or in other words, by beginning to liquidate the company.

(d) Companies with negative working capital

Companies with a negative working capital raise a fundamental question for the financial analyst. Should they be allowed to reduce their shareholders’ equity on the strength of their robust, positive cash position?

Can a company with a negative working capital maintain a financial structure with relatively little shareholders’ equity? This would seem to be an anomaly in financial theory. On the practical level, we can make two observations.

Firstly, under normal operating conditions, the company’s overall financing structure is more important and more telling than the absolute value of its negative working capital.

Let’s look at companies A and B, whose balance sheets are as follows:

| Company A | |||

| Fixed assets | 900 | Shareholders’ equity | 800 |

| Working capital | 1000 | Net debt | 1100 |

| Company B | |||

| Fixed assets | 125 | Shareholders’ equity | 100 |

| Cash & cash equiv. | 105 | Neg. working capital | 130 |

Most of company A’s assets, in particular its working capital, are financed by debt. As a result, the company is much more vulnerable than company B, where the working capital is well into negative territory and the fixed assets are mostly financed by shareholders’ equity.

Secondly, a company with a negative working capital reacts much more quickly in times of crisis, such as recession. Inertia, which hinders positive working capital companies, is not as great.

Nevertheless, a negative working capital company runs two risks:

- The payment terms granted by its suppliers may suddenly change. This is a function of the balance of power between the company and its supplier, and unless there is an outside event, such as a change in the legislative environment, such risk is minimal. On the contrary, when a company with a negative working capital grows, its position vis-à-vis its suppliers tends to improve. Nevertheless, the tendency (including regulatory) to reduce payment periods has a mechanically negative impact on firms with negative working capital.

- A contraction in the company’s business volume can put a serious dent in its financial structure. Already negative working capital becoming less and less negative will prompt a cash drain on a company’s financial resources, pushing it into financial difficulties unless it is able to use its available cash, if any, or raise new debt.

Section 12.3 Case study: ArcelorMittal6

With the exception of 2011, during which ArcelorMittal’s working capital increased sharply as a result of a 20% leap in sales, free cash flows after financial expense were positive and from 2011 to 2015 amounted to $5.2bn. This performance is explained by working capital in constant decline, which generated resources of $3.2bn (see Section 11.5), and by limited capital expenditure (see Section 11.5), which was $2bn less than free cash flow.

Given that dividends paid out since 2011 ($3.7bn) absorbed the proceeds of the 2013 capital increase ($3.6bn), all free cash flows after financial expense since 2011 ($5.2bn) were used to reduce net bank borrowings and long-term debt. At the close of 2015, these amounted to $20.3bn, excluding pension fund commitments of an additional $9.2bn.

Notwithstanding the 20% reduction in net debt excluding pension fund commitments, the net bank borrowings and long-term debt to EBITDA ratio has deteriorated sharply, from 2.7 in 2011 to 5.3 in 2015, and 7.8 when pension fund commitments are taken into account. This explosion is explained by the fact that EBITDA was divided by 2.6. Given this large figure, the reader will hardly be surprised to learn that ArcelorMittal launched a $3.5bn capital increase in early 2016, seeking to deleverage by this amount, and that it has suspended dividend payments from 2016.

ArcelorMittal’s debt is made up entirely of bonds with maturity dates spread over several years ($1.1bn in 2016, and then $2.5bn per year until 2020), with an average maturity of 6.2 years, which means that there is no medium-term liquidity risk, unless there is another slump in the steel market. However, in the short term, the group’s liquidity is more precarious with outstanding liabilities accounting for an increasingly larger share of current assets (from 78% in 2011 to 93% in 2015), when the value of inventories (half of current assets) is very uncertain in the current context. Fortunately, ArcelorMittal has undrawn lines of credit amounting to $6bn expiring in 2018 and 2020, subject to covenants that set a maximum net debt to EBITDA ratio of 4.25, calculated on an EBITDA that excludes restructuring costs, unlike our recommendations (see Section 9.2) and our calculations. So the 2016 capital increase will go a long way to improving short-term liquidity.

Summary

Exercises

Answers

Notes

1 See Chapter 37.

2 A glamour division is a fast-growing, high-margin division.

3 An investment fund that buys the debt of companies in difficulty or subscribes to equity issues with the aim of taking control of the company at a very low price.

4 Clause in debt contracts restricting the freedom of the borrower until debt is above a certain level. For more on debt covenants, see Chapter 39.

5 Also called “permanent financing”. This includes shareholders’ equity, which is never due, and debts maturing after one year.

6 The financial statements for ArcelorMittal are on pages 53, 65 and 155 .

Bibliography

- H. Almeida, M. Campello, Financial constraints, asset tangibility, and corporate investment, Review of Financial Studies, 20(5), 1429–1460, September 2007.

- R. Elsas, M. Flannery, J. Garfinkel, Financing major investments: Information about capital structure decisions, Review of Finance, 18(4), 1341–1386, July 2014.

- E. Morellec, Asset liquidity, capital structure and secured debt, Journal of Financial Economics, 61(2), 173–206, August 2001.