Chapter 36

Returning cash to shareholders

It’s all grist to the mill

Net income has only two possible destinations: either it is reinvested in the business in the form of internal financing or it is redistributed to shareholders in dividends or share buy-backs.

In fact, when the capital structure of the firm already corresponds to the target fixed by shareholders and management, every cent left in the company in the form of cash will only yield the short-term interest rate, i.e. much less than the cost of equity. Today this may even mean yielding a negative return given the negative interest rates in certain regions of the world. It is true that the financial risk of the firm is then reduced, but it is not what shareholders are looking for (shareholders theoretically manage financial risks at their portfolio level). In this context, it is very likely that shareholders will value it at less than a cent given the low return provided. After all, shareholders do not need the firm to place cash at the bank. All in all, failure to comply with this rule will most likely lead to value destruction.

Additionally, the business risk should be financed through equity; otherwise, the firm is likely to face strong liquidity issues at the first downturn. Conversely, a company that has reached economic maturity with a strong strategic position may reduce its equity financing and select a higher gearing. The business cash flows have become sufficiently sound to support the cash requirements of debt.

Section 36.1 Reinvested cash flow and the value of equity

1. Principles

An often-heard precept in finance says that a company ought to fund its development solely through internal financing – that is, by reinvesting its cash flow in the business. This position seemingly corresponds to the interests of both its managers and its creditors, and indirectly to the interests of its shareholders:

- For shareholders, reinvesting cash flow in the business ought to translate into an increase in the value of their shares and thus into capital gains on those shares. In virtually all of the world’s tax systems, capital gains are taxed less heavily than dividends. Other things being equal, shareholders will prefer to receive their returns in the form of capital gains. They will therefore look favourably on retention rather than distribution of periodic cash flows.

- By funding its development exclusively from internal sources, the company has no need to go to the capital markets – that is, to investors in shares or corporate bonds – or to banks. For this reason, its managers will have greater freedom of action. They, too, will look favourably on internal financing.

- Lastly, as we have seen, the company’s creditors will prefer that it rely on internal financing because this will reduce the risk and increase the value of their claims on the company.

This precept is not wrong, but here we must emphasise the dangers of taking it to excess. A policy of always or only reinvesting internally generated cash flow postpones the financial reckoning that is indispensable to any policy. It is not good for a company to be cut off from the capital markets or for capital mobility to be artificially reduced, allowing investments to be made in unprofitable sectors. The company that follows such a policy in effect creates its own internal capital market independent of the outside financial markets. On that artificial market, rates of return may well be lower, and resources may accordingly be misallocated.

The sounder principle of finance is probably the one that calls for distributing all periodic earnings to shareholders and then going back to them to request funding for major projects. In the real world, however, this rule runs up against practical considerations – substantial tax and transaction costs and shareholder control issues – that make it difficult to apply.

2. Internal financing and value creation

We begin by revisiting a few truisms.

- The reader should fully appreciate that, given unchanged market conditions, the value of the company must increase by the amount of profit that it reinvests. This much occurs almost automatically, one might say. The performance of a strategy that seeks to create “shareholder value” is measured by the extent to which it increases the value of shareholders’ equity by more than the amount of reinvested earnings.

- The apparent cost of internal financing is nil. This is certainly true in the short term, but what a trap it is in the long term to think this way! Does the reader know of any good thing that is free, except for things available in unlimited quantity, which is clearly not the case with money? Reinvested cash flow indeed has a cost and, as we have learned from the theory of markets in equilibrium, that cost has a direct impact on the value of the company. It is an opportunity cost. Such a cost is, by nature, not directly observable – unlike the cost of debt, which is manifested in an immediate cash outflow. As we explained previously, retaining earnings rather than distributing them as dividends is financially equivalent to paying out all earnings and simultaneously raising new equity capital. The cost of internal financing is therefore the same as the cost of a capital increase: to wit, the cost of equity.

- Does this mean the company ought to require a rate of return equal to the cost of equity on the investments that it finances internally? No. As we saw in Chapter 29, it is a mistake to link the cost of any source of financing to the required rate of return on the investment that is being financed. Whatever the source or method of financing, the investment must earn at least the cost of capital.1 By reinvesting earnings rather than borrowing, the company can reduce the proportion of debt in its capital structure and thereby lower its cost of debt. In equilibrium, this cost saving is added on top of the return yielded by the investment to produce the return required by shareholders. Similarly, an investment financed by new debt needs to earn not the cost of debt, but the cost of capital, which is greater than the cost of debt. The excess goes to increase the return to the shareholders, who bear additional risk attributable to the new debt.

- Retained earnings add to the company’s financial resources, but they increase shareholder wealth only if the rate of return on new investments is greater than the weighted average cost of capital. If the rate of return is lower, each euro invested in the business will increase the value of the company by less than one euro, and shareholders will be worse off than if all the earnings had been distributed to them. This is the market’s sanction for poor use of internal financing.

Consider the following company. The market value of its equity is 135, and its shareholders require a rate of return of 7.5%:

| Year | Book value of equity | Net profit | Dividend (Div) | Market value of equity (V) P/E = 9 | Gain in market value (ΔV) | Rate of return (ΔV + Div)/V |

| 1 | 300.0 | 15.0 | 4.5 | 135.0 | ||

| 2 | 310.5 | 15.6 | 4.7 | 140.4 | 5.4 | 7.2% |

| 3 | 321.4 | 16.2 | 4.9 | 145.8 | 5.4 | 7.1% |

| 4 | 332.7 | 16.8 | 6.7 | 151.2 | 5.4 | 8.0% |

Annual returns on equity are close to 7.5%. Seemingly, shareholders are getting what they want. But are they?

To measure the harm done by ill-advised reinvestment of earnings, one need only compare the change in the book value of equity over four years (+32.7) with the change in market value (+16.2). For each €1 the shareholders reinvested in the company, they can hope to get back only €0.50. Of what they put in, fully half was lost – a steep cost in terms of foregone earnings.

Beware of “cathedrals built of steel and concrete” – companies that have reinvested to an extent not warranted by their profitability!

Reinvesting earnings automatically causes the book value of equity to grow. It does not cause symmetrical growth in the market value of the company unless the investments it finances are sufficiently profitable – that is, unless those investments earn more than the required rate of return given their risk. If they earn less, shareholders’ equity will increase but shareholders’ wealth will increase less than the amount of the reinvested funds. Shareholders would be better off if the funds that were reinvested had instead been distributed to them.

In our example, the market value of equity (151) is only about 45% of its book value (333). True, the rate of return on equity (5%) is, in this case, far below the cost of equity (7.5%).

More than a few unlisted mid-sized companies have engaged in excessive reinvestment of earnings in unprofitable endeavours, with no immediate visible consequence on the valuation of the business.

The owner-managers of such companies get a painful wake-up call when they find they can sell the business, which they may have spent their entire working lives building, only for less than the book value (restated or not) of the company’s assets. The sanction imposed by the market is severe.

When this is not the case, the company is better off giving back the money to shareholders rather than investing it in projects not yielding their cost of capital. Shareholders will then have the opportunity to invest the funds in new sectors that require equity to finance their developments.

3. Internal financing and taxation

From a tax standpoint, reinvestment of earnings has long been considered a panacea for shareholders. It ought to translate into an increase in the value of their shares and thus into capital gains when they liquidate their holdings. Generally, capital gains are taxed less heavily than dividends.

Other things being equal, then, shareholders will prefer to receive their income in the form of capital gains and will favour reinvestment of earnings. Since the 1990s, however, as shareholders have become more of a force and taxes on dividends have been reduced in most European countries, this form of remuneration has become less attractive.

4. Internal financing, shareholders and lenders

We have seen (cf. the discussion of options theory in Chapter 34) that whenever a company becomes more risky, there is a transfer of value from creditors to shareholders. Symmetrically, whenever a company pays down debt and moves into a lower risk class, shareholders lose and creditors gain.

Reinvestment of earnings can be thought of as a capital increase in which all shareholders are forced to participate. This capital increase tends to diminish the risk borne by creditors and thus, in theory, makes them better off by increasing the value of their claims on the company.

The same reasoning applies in reverse to dividend distribution. The more a company pays out in dividends, the greater the transfer of value from creditors to shareholders.

5. Internal financing, shareholders and managers

As we will see in Section 36.3, under the agency theory approach, internal financing represents a major issue in the relationship between shareholders and managers. Internal financing represents a blank cheque for managers without any control by shareholders. Internal financing is therefore one of the main sources of conflict between managers and shareholders.

Section 36.2 Internal financing and financial criteria

1. Internal financing and organic growth

Growth of the equity of a firm that does not issue shares depends on its return on equity and its payout ratio.

The net profit of a firm with equity of 100 and a return on equity of 15% will be 15. If its payout ratio is 1/3, it will keep 2/3 of its profits, i.e. 10. Equity will then become 110 the next year, a 10% increase, as shown in the table below:

| Year | Book value of equity at beginning of year | Net profit (15% of equity) | Retained earnings | Book value of equity at end of year |

| 1 | 100.0 | 15.0 | 10.0 | 110.0 |

| 2 | 110.0 | 16.5 | 11.0 | 121.0 |

| 3 | 121.0 | 18.2 | 12.1 | 133.1 |

| 4 | 133.1 | 20.0 | 13.3 | 146.4 |

The book value of a company that raises no new money from its shareholders depends on its rate of return on equity and its dividend payout ratio.

The growth rate of book value is equal to the product of the rate of return on equity and the earnings retention ratio, which is the complement of the payout ratio.

We have:

where g is the rate of growth of shareholders’ equity,2 ROE (return on equity) is the rate of return on the book value of equity and d is the dividend payout ratio.

This is merely to state the obvious, as the reader should be well aware.

In other words, given the company’s rate of return on equity, its reinvestment policy determines the growth rate of the book value of its equity.

2. Models of internal growth

If capital structure is held constant, growth in equity allows parallel growth in debt and thus in all long-term funds required for operations. We should make it clear that here we are talking about book values, not market values.

We need only recall that the rate of return on book value of equity is equal to the rate of return on capital employed adjusted for the positive or negative effect of financial leverage (gearing) due to the presence of debt:

or:

where g is the growth rate of the company’s capital employed at constant capital structure and constant rate of return on capital employed (ROCE).

This is the internal growth model.

It is clear that the rates of growth of revenue, production, EBITDA and so on will be equal to the rate of growth of book equity if the following ratios stay constant:

To illustrate this important principle, we consider a company whose assets are financed 50% by equity and 50% by debt, the latter at an after-tax cost of 5%. Its after-tax return on capital employed is 15%, and 80% of earnings are reinvested. Accordingly, we have:

| Period | Book equity at beginning of period | Net debt | Capital employed | Operating profit after tax | Interest expenses after tax | Net profit | Dividends | Retained earnings | Book equity at end of period |

| 1 | 100 | 100 | 200 | 30 | 5 | 25 | 5 | 20 | 120 |

| 2 | 120 | 120 | 240 | 36 | 6 | 30 | 6 | 24 | 144 |

| 3 | 144 | 144 | 288 | 43.2 | 7.2 | 36 | 7.2 | 28.8 | 172.8 |

This gives us an average annual growth rate of book equity of:

The reader can verify that, if the company distributes half its earnings in dividends, the growth rate of the book value of equity falls to:

The growth rate of capital employed thus depends on the:

- rate of return on capital employed: the higher it is, the higher the growth rate of financial resources;

- cost of debt: the lower it is, the greater the leverage effect, and thus the higher the growth rate of capital employed;

- capital structure;

- payout ratio.

In a situation of equilibrium, then, shareholders’ equity, debt, capital employed, net profit, book value per share, earnings per share and dividend per share all grow at the same pace, as illustrated in the example above. This equilibrium growth rate is commonly called the company’s growth potential.

3. Additional analysis

The first of the models above – the internal growth model – assumes all the variables are growing at the same pace and also that returns on funds reinvested by organic growth are equal to returns on the initial assets. These are very strong assumptions.

Suppose a company reinvests two-thirds of its earnings in projects that yield no return at all. We would observe the following situation:

| Period | Book equity at beginning of period | Net profit | Return on equity | Dividends | Retained earnings | Book equity at end of period |

| 1 | 100 | 15 | 15.0% | 5 | 10 | 110 (+10.0%) |

| 2 | 110 | 15 (+0%) | 13.6% | 5 (+0%) | 10 | 120 (+9.1%) |

| 3 | 120 | 15 (+0%) | 12.5% | 5 (+0%) | 10 | 130 (+8.3%) |

We see that if net profit and earnings per share do not increase, then growth of shareholders’ equity slows and return on equity declines because the incremental return (on the reinvested funds) is zero.

If, on the other hand, the company reinvests two-thirds of its earnings in projects that yield 30%, or double the initial rate of return on equity, all the variables will rise.

| Period | Equity at beginning of period | Net profit | Rate of return on equity | Dividends | Retained earnings | Equity at end of period |

| 1 | 100 | 15 | 15.0% | 5 | 10 | 110 (+10.0%) |

| 2 | 110 | 18 (+20%) | 16.4% | 6 (+20%) | 12 | 122 (+10.9%) |

| 3 | 122 | 21.6 (+20%) | 17.7% | 7.2 (+20%) | 14.4 | 136.4 (+11.8%) |

Although the rate of growth of book equity increases only slightly, the earnings growth rate immediately jumps to 20%.

The rate of growth of net profit (and earnings per share) is linked to the marginal rate of return, not the average.

Here we see that there are multiplier effects on these parameters, as revealed by the following relation:

This means that, barring a capital increase, the rate of growth of earnings (or earnings per share) is equal to the marginal rate of return on equity multiplied by the earnings retention ratio (1 – dividend payout ratio).

Section 36.3 Why return cash to shareholders?

Funds returned to shareholders do not generally match the funds that could not be invested, at least the cost of capital. Beyond this simple theory, other factors need to be taken into account.

1. Dividends and equilibrium markets

In markets in equilibrium, payment of a dividend has no impact on the shareholder’s wealth, and the shareholder is indifferent about receiving a dividend of one euro or a capital gain of one euro.

At equilibrium, by definition, the company is earning its cost of equity. Consider a company, Equilibrium plc, with share capital of €100 on which shareholders require a 10% return. Since we are in equilibrium, the company is making a net profit of €10. Either these earnings are paid out to shareholders in the form of dividends, or they are reinvested in the business at Equilibrium plc’s 10% rate of return. Since that rate is exactly the rate that shareholders require, €10 of earnings reinvested will increase the value of Equilibrium plc by €10 – neither more nor less. Thus, either the shareholders collectively will have received €10 in cash, or the aggregate value of their shares will have increased by the same amount.

If the company pays out a high proportion of its earnings, its shares will be worth less but its shareholders will receive more cash. If it distributes less, its shares will be worth more (provided that it reinvests in projects that are sufficiently profitable) and its shareholders will receive less cash – but the shareholder, if he wishes, can make up the difference by selling some of his shares.

In a universe of markets in equilibrium, paying out more or less in dividends will have no effect on shareholder wealth. Companies should thus not be concerned about dividend policy and should treat dividends as an adjustment to cash flow. This harks back to the Modigliani–Miller approach to financial policy: there is no way to create lasting value with merely a financing decision.

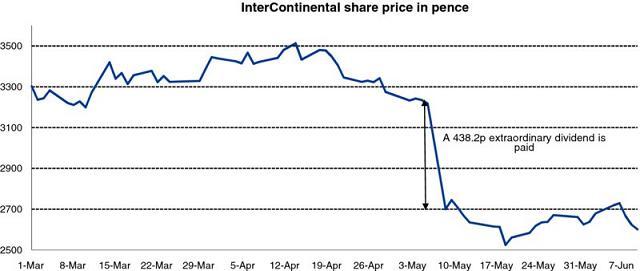

The chart below plots the share price of InterContinental, which in May 2016 paid an extraordinary dividend of 438.2p in cash. The price of the shares adjusted immediately.

Dividend at InterContinental

Source: Datastream

Another demonstration can be found in the fact that a stock market order, if not executed, is automatically adjusted to take into account the payment of a dividend that has taken place after the order has been submitted.

In any case, it’s a fallacy to present dividend distribution as remuneration for shareholders, similar to salaries for the company’s employees.

The wealth of the employee increases with the salary. Conversely, the wealth of shareholders is not modified by the dividends they receive: while they are certainly happy about getting this periodical remuneration, they must consider that the value of their shares will fall by an equivalent amount.

What about firms that have never paid a dividend, like Facebook or Berkshire Hathaway (Warren Buffet’s firm)? Have they never remunerated their shareholders? Of course they have, and those firms have been very good investments for their shareholders. The return for shareholders comes from the increase in value of their portfolios (including dividends, if any). The dividend is taken into account not because it represents a return for the shareholder, but solely to compensate the drop in value of the share following the dividend payment.

2. Dividends as signals

Equilibrium market theory has a hard time finding any good reason for dividends to be paid at all. Since they do exist in the real world, new explanations must be sought for the earnings distribution problem.

A justification for the existence of dividends is proposed by the theory of signalling, around which an entire literature has developed, mainly during the 1980s.

The financial information that investors get from companies may be biased by selective disclosure or even manipulative accounting. Managers are naturally inclined to present the company in the best possible light, even if the image they convey does not represent the exact truth. Companies that really are profitable will therefore seek to distinguish themselves from those that are not through policies that the latter cannot imitate because they lack the resources to do so. Paying dividends is one such policy, because it requires the company to have cash. A company that is struggling is not able to imitate a company that is prospering.

For this reason, dividend policy is a means of signalling that cannot be faked, and managers use it to convince the market that the picture of the company they present is the true one.

Dividend policy is also a way for the company’s managers to show the market that they have a plan for the future and are anticipating certain results. If a company maintains its dividend when its earnings have decreased, that signals to the market that the decline is only temporary and earnings growth will resume. Dividends are paid a few months after the close of the year, therefore the level of the dividend depends on earnings during both the past and the current period. That level thus provides information – a signal – about expected earnings during the current period.

If a firm maintains its dividend while its profits are decreasing, it tells the market that the decrease is temporary and that the increase in profit should resume soon. For example, the mining group Rio Tinto saw its share price increase by 2% as it announced a 12% increase in dividends when profits were dropping by 30%. In contrast, if it drastically reduces or cancels its dividend, it sends a signal on its earnings prospects that will most likely be analysed negatively.

A dividend reduction, though, is not necessarily bad news for future earnings. It might also indicate that the company has a new opportunity and needs to invest. Hence we observed, in the late 1990s, a shift of companies traditionally positioned on mature markets and sectors to geographies and businesses with more growth potential.

Managements will need to avoid the trap of an increase in dividend being interpreted by the market as a decrease in investment opportunities.

3. Dividends and agency theory

Creditors and managers are seen as having a common interest in favouring reinvestment of earnings. When profits are not distributed, “the money stays in the business”, whereas shareholders “always want more”.

If the manager directs free cash flow into unprofitable investments, his ego may be gratified by the size of the investment budget, or his position may become more secure if those investments carry low risk.

In addition, retained earnings are one source of financing about which not much disclosure is necessary. The cost of any informational asymmetry having to do with internal financing is therefore very low. It is not surprising that, as predicted by Jensen (1986) and observed in a study conducted by Harford (1999), companies that have cash available make less profitable investments than other companies. Money seems to burn a hole in managers’ pockets.

As presented by Jensen (1986), there is a sanction, however, for taking reinvestment to excess: the takeover bid or tender offer in cash or shares (for listed firms).

If a management team performs poorly, the market’s sanction will, sooner or later, take the form of a decline in the share price. If it lasts, the decline will expose the company to the risk of a takeover. Assuming the managers themselves do not hold enough of the company’s shares to ensure that the tender offer succeeds or fails, a change of management may enable the company to get back on track by once again making investments that earn more than the cost of capital, and thereby lead to a rise in the share price.

The threat of a takeover is not theoretical, it has struck a number of mismanaged groups (Aventis, Reuters, ABN Amro, Club Med, Syngenta, etc.), but the takeover often comes later, after years of underperformance. The dividend policy can help to prevent this situation.

By requiring managers to pay out a fraction of the company’s earnings to shareholders, dividend policy is a means of imposing “discipline” on those managers and forcing them to include in their reckoning the interest of the company’s owners. A generous dividend policy will increase the company’s dependence on either shareholders or lenders to finance the business.

In either case, those putting up the money have the power to say no. In the extreme, shareholders could demand that all earnings be paid out in dividends in order to reduce managers’ latitude to act in ways that are not in the shareholders’ interest. The company would then have to have regular rights issues, to which shareholders would decide whether to subscribe based on the profitability of the projects proposed to them by the managers. This is the virtuous cycle of finance.

Although attractive intellectually because it greatly reduces the problem of asymmetric information, this solution runs up against the high costs of carrying out a capital increase – not just the direct costs, but the cost in terms of management time as well.

Bear in mind also that creditors watch out for their interests and tend to oppose overly generous dividends that could increase their risk, as we saw in Chapter 34.

4. Because shareholders wish it

Baker and Wurgler (2004a,b) have demonstrated that in some periods shareholders demand dividends and are thus ready to pay higher prices for more generous shares. Since 2002 we have been exactly in this situation. Whilst our readers know that dividends do not enrich shareholders (since the value of the shares falls correspondingly), shareholders may nonetheless be happy about receiving more dividends. A good example of this attitude was provided by John Rockefeller in the 1920s: “Do you know the only thing that I like? To cash in my dividends!”

Conversely, there are some periods when investors prefer companies that retain most of their earnings. In these cases, the stock market penalises generous shares, as happened in the second half of the 1990s: at the end of 1998, Telefónica announced the suppression of its dividend for financing its expansion in Latin America. At the announcement, the stock increased by 9%.

The reader may wonder why a series of opposite phases are often observed. We believe that there is no better answer than the existence of fads, even in finance. Waves of optimism lead to the reinvestment of earnings; conversely, pessimism pushes companies to distribute a higher portion of earnings.

5. To provide shareholders with cash

This is particularly true for private companies, but can also apply to small listed companies with low liquidity on the market. Shareholders are human beings after all; they have needs and may need cash for day-to-day life.

Family-owned companies may need to pay a regular dividend to allow their shareholders to pay their annual taxes without having to sell part of their holding.

6. To modify the firm’s shareholder base

In most cases, giving back cash to shareholders means giving back the same amount on each share. If this is not the case (i.e. through share buy-backs), the shareholder base of the company will be modified. As we will see in the next chapter, the control of the firm can be reinforced by key shareholders not participating in share buy-backs. Shareholders receiving cash will then be diluted.