Until now, we have focused on collecting, selecting, and shaping stories. Now, let’s discuss how to use stories to communicate outside of the design team.

For many practitioners, explaining design ideas and the sources of those ideas to managers is difficult. We get enthusiastic about the specifics of the idea, drowning the audience in details before they comprehend the big picture. Or we struggle to make a connection between the idea and the real-world problem it solves. What we need is a way to engage their imagination, so they cannot simply hear the new idea, but contribute to it and thereby invest in it.

That’s where stories come in. They don’t replace the entire presentation; there’s still a time and a place for details of technology, marketing, and budgets. The role for stories in a management presentation is to get the audience’s attention, to set a context for the rest of the data, and usually to inspire action by leaving them with a clear image.

Films are full of scenes in which someone changes the minds of a group of people by telling a story. The characters always seem to have just the right words and speak beautifully. With that image in mind, you may be worried that you aren’t a good enough performer to tell a story well. Don’t worry. You may not be a great storyteller, but anyone can be a good one. As long as you are clear about your goals, listen to your audience, and find a story that bridges the gap between your goals and those of the audience, you have everything you need to make stories work for you.

Don’t think you get just one chance to tell a story, and that it has to be perfect the first time. One of the great things about using stories to communicate design ideas is that you can refine them with input from your audience.

In the end, it’s the listener’s job to build the story. All you provide is the necessary information, tailored to the perspective and preconceptions of your audience. In doing so, you shape the experience so that the story that emerges in the group is a shared story, not a dozen or more wildly different versions.

It’s a careful balancing act: The more you allow the people to build their own story around the structure and details you provide, the more engaged they are in their story. If you give them too much data, too many facts and details, they have nothing to do and will likely be bored. If you give them too little to work with, they may start building a story that is very different than the one you have in mind, which could cause disruption and annoyances in a presentation.

Another obstacle is that audiences vary. In user experience, the biggest difference between audiences usually lies in their role within the project or company. You may have project sponsors who are interested in the bottom line benefit, technologists who want it done the simplest way, design teams looking for new ideas, and marketers looking for insight into consumer thinking, all in the same presentation.

In any business setting, people come to a meeting (and hear your story) with different expectations and agendas. Even with a single audience, one you know well, there may be a lot of variation from day to day. No matter how good your preparation, you still have to pay attention to their body language, facial expressions, and comments while you are sharing your story to see if it is working and if the story the audience is building is the one you intended.

Sometimes, you will be in a situation where you know your audience well. Perhaps they are your colleagues or a client you work with on a regular basis. But you may also be thrown into a situation where you have little idea how to connect.

It may seem obvious, but the first thing you need to do in this situation is to ask your listeners what they want to hear and then really listen to their answers.

By starting with a brief listening exercise, you not only get a better idea of the expectations the audience has brought to the room, but you also help the people in the room understand how diverse or similar they are. They may be more tolerant of material that does not seem immediately relevant to them once they know why you have chosen to include it.

Although each audience has its own dynamic, there are a few types that you meet often enough to generalize about them. This is not an exhaustive list, but a few of the most common personas:

Strategic leaders: People who need to generate and maintain a common vision for their company, group, or products.

Managers: People with a mission—often a product—who need to make the decisions that keep their entire team on track toward a common goal.

Technical experts: People who implement a vision, making the myriad detailed decisions that add up to a product or service.

Your audience may include people who are experts in your field or in some part of your project. They may have their own views about the subject of your story and may listen for details that you get “wrong.” We’ll talk more about audiences with a special relationship to the story in Chapter 12.

Your audience may also include other people in user experience who are not part of your immediate team. We hope that all of the people involved in user experience design work together, but that is not always the case. If you are presenting to user experience colleagues, consider what details help make a story authentic for them. Chapter 12 also looks at how a story might change to take into consideration the relationship between you and the audience.

Leaders, especially in strategic management, must connect the business and the market (see Figure 10-1). The stories you tell for leaders should do the same thing, connecting your design or research to their concerns.

When you create a story for a leader, show how the idea you are “selling” makes a bridge between users and the business. For example, you can try one of these strategies:

Identify a point-of-pain that users experience and then show a solution.

Identify a gap in the market and show a way to fill it with a new product or a change in a current one.

Identify a new approach by reconfiguring common or existing components in an unconventional way.

Identify trends in the user experience of your customers and how that is affecting the business.

Stories can be particularly useful when you need to explain a disruptive idea, an innovation that is counterintuitive, or an idea for which there are few metrics or data points.

It’s hard to separate user experience stories for leaders from stories about leaders and leadership.

Leadership is partially about generating and maintaining a common vision and sense of purpose. Saying, “Follow me!” is not leadership. Showing how everyone’s efforts are relevant, contributory, necessary, and ultimately self-rewarding is leadership. All that can be done through telling the right story at the right time.

User experience is not the only discipline to notice the power of storytelling. There is a growing body of work on corporate storytelling focusing on how leaders can use stories to shape and communicate strategy. Two of the leading authors in this work are Stephen Denning (The Springboard and The Secret Language of Leadership) and Annette Simmons (Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins).

For both Simmons and Denning, stories are a natural way for leaders to communicate. They see the leader’s role as inspiring others to action, using stories to spark their imagination and engage them in working toward a goal. In this view, memos and long reports are counterproductive. Denning sees stories as a way to avoid both a hierarchical leadership style and long arguments about details of strategy and direction. Simmons recognizes the ability of a story to deliver a practical vision.

“The word ‘vision’ has been distorted for many of us by bad experiences of smarmy consultants, endless management retreats, and oversold and underdelivered promises. Story forces substance back into the vision process. Laminated cards with core values and quippy ‘$2 billion by 2010’ sound-bite visions are exposed as superficial and one-dimensional when compared to vision stories. When you apply the discipline of interpreting any vision by way of a story, the process inevitably exposes any gaping holes that beg the questions: What does this mean? To whom? And who benefits if I get there? Exploitation, superficiality, and unintended outcomes are more likely to be exposed by the rigors of storytelling.”

—Annette Simmons, Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins

Because stories are a familiar way for leaders to communicate, you can tap into this familiarity to tell stories in a way that will seem natural to them.

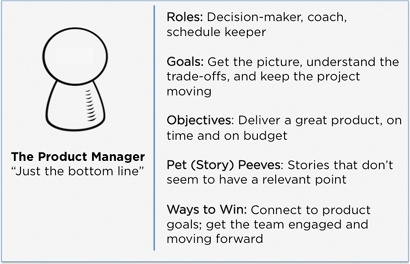

Managers can be an easy audience because they often have clear goals (see Figure 10-2). If you can speak to their issues, crisply and clearly, they will listen.

Managers don’t usually have a lot of time to spare. More often than not, they like short, concise meetings, not leisurely brainstorming sessions or deep dives into user research data. Don’t plan to tell long detailed stories to this audience. Instead, think about when a story can have the most impact.

Use stories to kick off a new idea, especially if you need a bit of context to explain how it will work. For this situation, the ability of stories to pack a lot of detail into a few words works for you.

If you are bringing bad news from user research, such as the discovery that the target audience doesn’t really want or like a new product idea, make sure that you show how the story is typical of a group of people who are important as customers, users, or other stakeholders. If you are presenting a new idea, find a way to connect it to a well-known situation, so that it seems more plausible. You might even do both in one story: present a problem and a solution in a simple narrative. Most importantly, don’t get bogged down in detailed specifications or technology.

In this example, a rough sketch of a new idea illustrated the story. Instead of simply plopping an idea into the middle of the meeting, the story provided a context to justify the idea. These sketches need to be concrete enough to suggest a specific direction, but open enough to accept input from the audience.

Another goal for a management story is to get a team engaged. Once people have begun thinking about an idea or how to solve a problem, it’s harder to drop the topic or reject an idea out of hand. For these stories, you might focus on creating a vivid picture full of juicy images.

In many organizations, product managers are also champions for the product and will have their own stories. These are the stories they use to motivate internal stakeholders like sales and marketing and the stories they tell to their own customers or clients. You might think about how your story will feed and change theirs.

Sometimes, you have to calm fears that changes to a product or service will cost people their jobs. Ian Roddis, Sarah Allen, Viki Stirling, and Caroline Jarrett found this out when they began work on the Open University Web site. The people at the student registration service were often the only voice a prospective student might hear before enrolling. When the Web site was developed with the promise that it would answer questions about the OU, this staff worried that it would take away their work. An analysis of email traffic showed that although there were many routine inquiries, which could easily be handled online, there were just as many that were the sort of question only a live person could answer. Armed with this user experience data, they changed the way they introduced their work to focus on reducing the “clutter” so that the support staff would have the time to provide good answers to difficult questions.

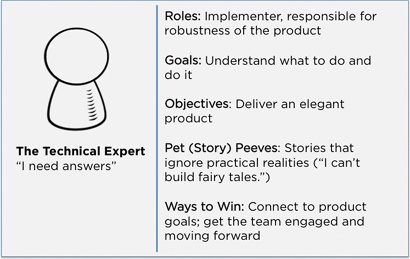

Technical audiences can be difficult to reach with stories, especially if the story is not firmly grounded in real details, providing concrete data for left-brain thinkers (see Figure 10-3).

Technical audiences can be sticklers for details. Often, this can be useful, especially when you are working on ideas that are technically challenging. You may have to deal with someone who seems to be listening only for inaccuracies in your stories:

Person 1: I was thinking that we could organize the form like this (shows a mockup). It would have a lot of advantages for our users because I’ve changed the flow so that the fields they use the most are at the top of the page.

Person 2: (interrupting) There’s a problem here. You’ve got a misspelling on the mockup, but the real problem is that you’ve drawn the fifth field too small to fit a really long entry.

This is a defensive mechanism, and may mean that your story is making them uncomfortable in some way. One way to prepare for a technical audience is to keep your stories firmly grounded in their technical reality. Craft your stories to avoid each of these pitfalls:

Use representative characters and situations. Usually, stay as close to the status quo as possible. Be ready to back up your choices with hard data. The one exception is a situation when the point of the story is to show that there are types of users you don’t know enough about.

Make the action of the story specific and tangible. The story does not have to describe interactions technically, but think carefully about what steps or details will be important in creating a credible story for this audience.

Keep the story on track. You may love the rich detail you have gathered in your user research sessions, but make sure that the story doesn’t wander into pure description.

Decide which details will help make your point and focus on them. This is similar to the way wireframes or low-fidelity prototypes use visual techniques in early design deliverables.

Use technical terminology accurately. If you want to show how users talk about something, be careful to map their vernacular or idiom to the correct technical term. It’s important to show that you understand everyone clearly.

In short, be sure that your story matters to the audience. Tell a story with details that relate to resources and deliverables. Use clear images to promote understanding of what needs to be done. A good story for a technical audience must present a problem they feel they can solve almost immediately, or one so intriguing they are willing to work on solving it. The choice is yours, but the first option is usually easier.

Stephen Denning makes a similar point in Springboard Stories when he talks about altering the level and type of detail to make a story resonate with each audience. When he tells a story about the health worker in Zambia to a general audience, he might slide over the medical details. But those details are the ones that will make a story ring true for health workers.

Managing several audiences at once is more than just a challenge of balancing different needs. Sometimes, they have different viewpoints or worries. This can lead to a situation in which they have not been listening to each other—and may have difficulty listening to you.

Some corporate cultures find it hard to handle dissent or disagreement, so they smooth it over by not really listening to what is being said. Everyone politely takes their turn explaining their perspective on a problem, but no one points out when they are in conflict or don’t connect. Have you ever attended a kickoff meeting for a project and started to wonder if everyone was talking about the same project?

There is no magic wand that will let you take a project from a place where each group of stakeholders has a different vision to a happy ending. One solution is to use stories to tease out each group’s starting vision. Casting their visions as stories can make it easier to talk about differences without creating a political disaster. You can use pieces of each of the stories to weave them into a single story, bringing them closer together.

Adjusting to an audience isn’t just about making people feel good about themselves (though that’s not a bad thing, either). It’s about being able to hear what people are really saying and create the stories that let a user experience team excel.

The Story Factor and Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins, Annette Simmons

The Springboard: How Storytelling Ignites Action in Knowledge-Era Organizations and The Secret Language of Leadership, Stephen Denning

Storytelling in Organizations, John Seely Brown, Stephen Denning, Katalins Groh, Laurence Prusak, and Seth Kahan

Managing by Storying Around, David Armstrong

Wake Me Up When the Data Is Over, Lori Silverman

Around the Corporate Campfire, Evelyn Clark

When you are sharing stories with management, remember that they may be more focused on the point of the story than on the background of how it was created. This audience needs stories that help them understand easily. A good story for managing has the following criteria:

Has a clear point.

Opens doors to new ideas.

Shows behavior to get beyond demographics, data, and opinion and shows how it translates into user experience.

Is told from a perspective appropriate to the audience.

Puts a human face on data from user research data or other analytics.