Criminology and forensic science as we know them emerged in the 19th century, and had become well-established in criminal investigations by the turn of the 20th century. However, their origins lay in the 18th century, when there was great scientific progress in the fields of chemistry, physics, botany, zoology, geology, and anatomy. This increase in scientific knowledge led to a more rational, non-speculative, evidence-based approach to solving crimes, and opened up a wider field of possibilities for the police. Conan Doyle made Sherlock Holmes a pioneer of forensic analysis and the use of reasoning, and as a detective working in the 19th century he was in many ways ahead of his time.

The main contributors to the development of criminology as a science were German psychologist and neuroanatomist Franz Josef Gall (1758–1828) and the Italian sociologists Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794) and Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909). Beccaria published On Crimes and Punishments (1764), in which he argued that crime was an endemic trait of human nature; Lombroso rejected this idea, claiming that psychological, social, and inherited conditions predisposed a person toward criminal tendencies.

Reformer and politician Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850) created the first British police force. The policemen were called peelers or bobbies (after Peel’s nickname “Bob”), a term still in use today.

Urban expansion and crime

Rapid population growth and urbanization at the end of the 18th century—especially in London, Manchester, Liverpool, Edinburgh, and Glasgow, as well as many other industrial cities across Europe (particularly Paris)—presented new social challenges. Urban expansion created dense populations within which crimes could be concealed easily and criminals could move around unnoticed in the crowds. This meant that policing, crime control, and solving or resolving criminal cases of forgery, assault, burglary, homicide, and organized gang crime became pressing issues. Previously, crimes had been dealt with on a largely local basis, within small communities, based on local knowledge and relatively simple information-gathering. However, this often involved rumor, hearsay, or prejudice—hence, in part, the so-called “witch trials” of the 16th and 17th centuries, in which local scores were settled by invidious accusations.

The first professional police forces set up to investigate crimes came into existence in the early 19th century. In 1812, Eugène François Vidocq, a former criminal, established the Sûreté Nationale in Paris; it was a modest but ambitious operation that recruited other reformed criminals to its staff. In 1829, Robert Peel set up the Metropolitan Police Service, based at Scotland Yard in Whitehall, London, in consultation with Vidocq. It would be many years later that the burgeoning population of the US saw the creation of the Bureau of Investigation in 1908 and its cross-state federal remit, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which was introduced in 1935 under its first director, J. Edgar Hoover. The aim of these policing institutions was to centralize information-gathering and intelligence distribution on a national and even transnational basis. The International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol) was another French innovation, created in 1923 to share and disseminate information around the world.

In addition to a new style of policing, a different dimension of detection and crime resolution became necessary, using a range of new techniques and methodologies. The principal steps forward in this area during the 19th century (of which Conan Doyle was well aware) fell into three main categories: the gathering of intelligence, especially concerning the activities of the “underground” classes; the collection and collation of details and characteristics of criminal “types” (phrenology and anthropometry); and the scientific analysis of forensic material gathered at the scene of the crime—unique datasets such as fingerprints, photographic files, and traces of blood types. A fourth important element was the development of a range of new infrastructure systems: the popular press, railroads, an efficient postal service, and high-speed communications, especially the telegraph—all of which Holmes exploits extensively in solving the enigmas that confront him.

"Police are the public and the public are the police."

Sir Robert Peel

“Principles of Policing” (1829)

The Watch House in London’s Covent Garden was built in 1729. In 1829, the newly formed Metropolitan Police took it over as headquarters of F Division, controlled by Superintendent Thomas.

Intelligence-gathering

Since the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the accumulation of evidence against “suspects” was largely a matter driven by concerns of national security, especially in non-Catholic Reformist countries, worried by the threat of Catholic subversion—for instance, when there were plots in England to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I (the Babington Plot, 1585) and blow up Parliament and King James I (the Gunpowder Plot, 1605). This perceived danger led to a culture of “observation” and the incipient invasion of personal privacy. The system also relied on the interception of messages, and blackmailing and torturing possible suspects or their associates. Other countries, including Spain, France, Russia, the Habsburg Empire, and other European states, developed “secret police” forces whose sole purpose was information-gathering.

By the beginning of the 19th century, police forces across Europe had become extremely adept at compiling damning dossiers on thousands of individuals deemed suspicious for one reason or another. Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial (1925) is just one example of many that exemplify the sense of paranoia created by the state’s intrusion on personal liberty and privacy. On the other hand, the collection and collation of information from a wide variety of sources has undoubtedly prevented a huge number of criminal acts. Holmes sits somewhere in the middle of this conundrum: while preferring to rely on his personal observations, he equally does not eschew using intelligence and information from international police forces to help in his investigations.

"By the aid of phrenology, we have obtained a tolerably clear view… of the mind."

George Combe

Constitution of Man (1828)

The practice of phrenology

The classification of human “types” based on class, social background, and physical characteristics—founded on supposedly scientific methods dating back to the ancient Greek scientist Galen—began with the development of phrenology in Germany in the early 19th century. Franz Josef Gall claimed that the size and shape of the skull revealed the intelligence, personality, and moral faculties of the subject, and would therefore be useful in categorizing criminal types. Gall also produced “brain maps,” which divided the brain into 27 “organs” ranging from areas responsible for the sense of taste and smell to those provoking criminal urges.

These brain maps proved hugely popular, and by 1820 the Edinburgh Phrenological Society was set up by one of Gall’s disciples, George Combe, and his physician brother Andrew. Although the society was disbanded in 1870, the museum remained open until 1886. Conan Doyle would have been aware of the Society’s work and would probably have visited while he was studying medicine in Edinburgh. He incorporated these “criminal traits” in many of his male villains, describing them as being huge, bearded, and swarthy with a low brow—for example in “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons”, “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle”, and “The Adventure of the Speckled Band”.

This dubious pseudoscience persisted for well over a century, and was used to provide simplistic evaluations of racial hegemony. The Nazis were enthusiastic phrenologists, and SS commander Heinrich Himmler (1900–1945) amassed a collection of skulls that he used to demonstrate his arguments concerning racial superiority and criminality.

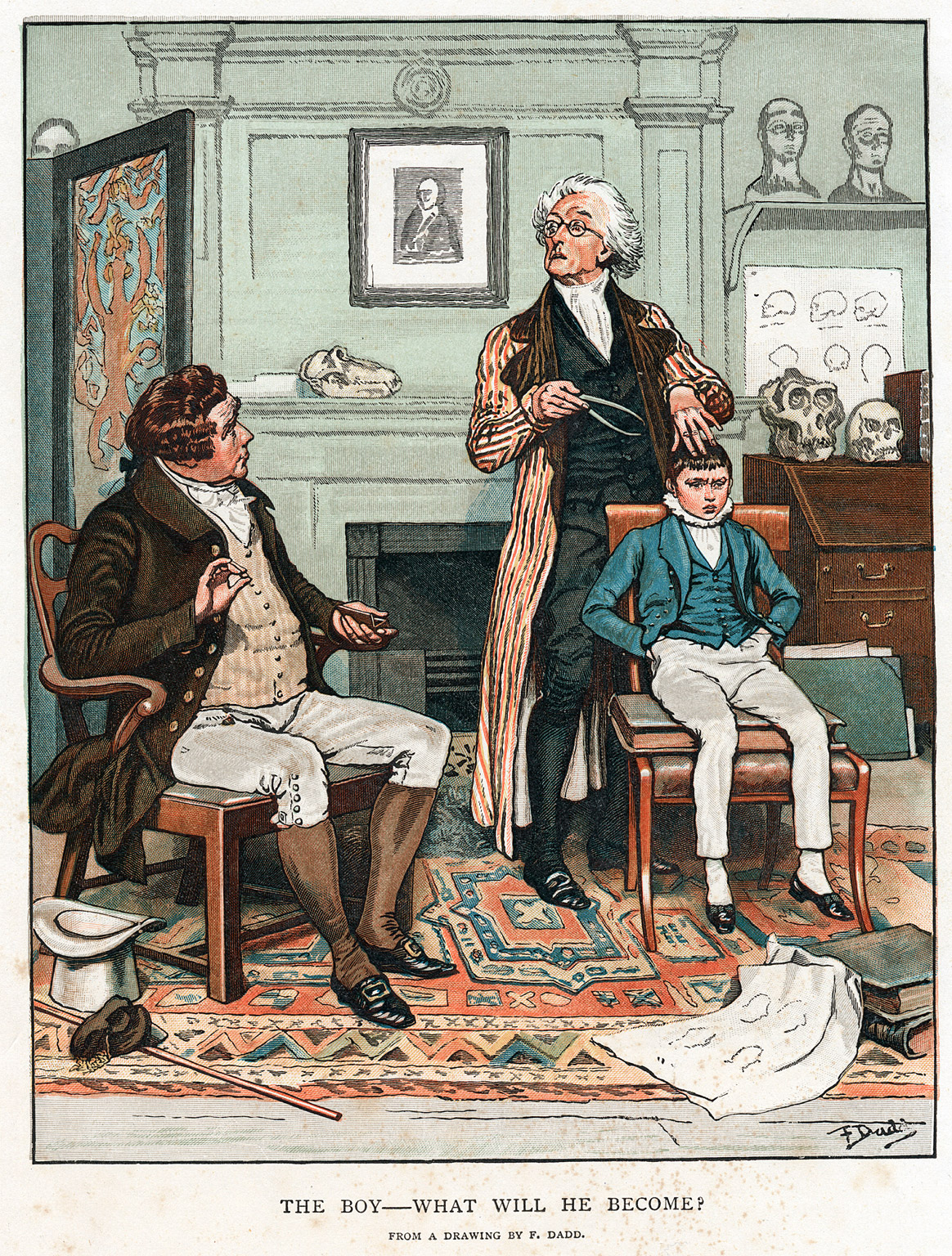

A phrenologist is seen here trying to assess a boy’s future by measuring the bumps on his head. Although not based on fact, this practice became popular in the early 19th century.

Anthropometry

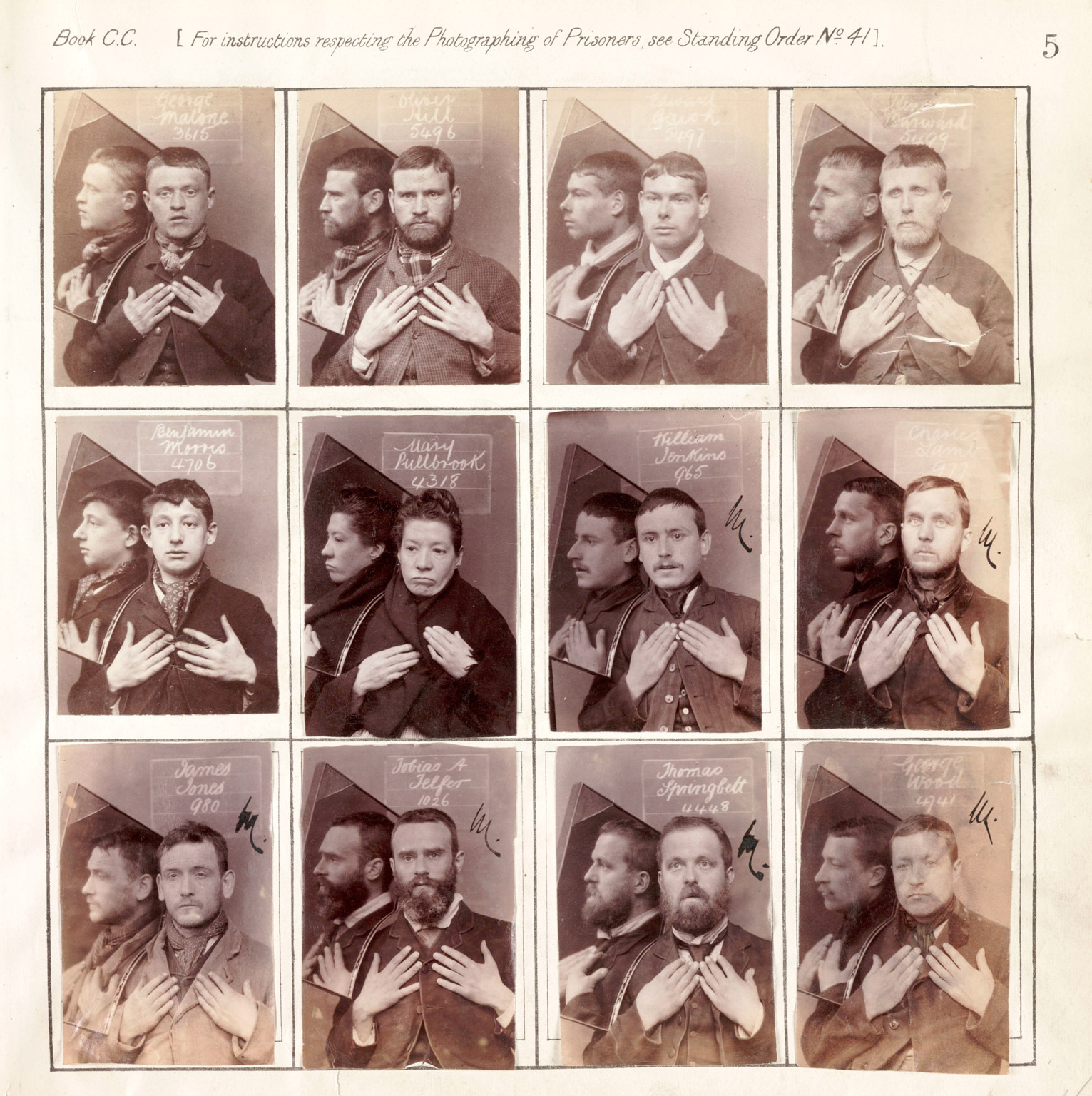

The basic tenets of phrenology were taken several steps further by the French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914), who developed the “science” of anthropometry. Bertillon carefully measured anatomical details (length of the neck, arms, legs, feet, and so on), of known or suspected criminals, subjecting them to humiliating physical analysis. His victims were also photographed—mainly at the time to analyze rather than to record their facial features, although this later formed the basis of the “mugshot” archives central to criminal archives today.

Handwriting analysis

Bertillon also developed another specialty—handwriting analysis. Started by French priest Jean-Hippolyte Michon, the “science” of graphology was based on the theory that a person’s handwriting is unique and reflects a range of underlying psychological characteristics. However, handwriting can be imitated and forged, faked or misidentified, so handwriting analysis is not reliable and has since been discredited. In an infamous case of 1894, Alfred Dreyfus, a French artillery officer of Jewish descent, was incorrectly convicted of treason. Bertillon’s identification of his handwriting was used as critical evidence in his conviction. Dreyfus was not exonerated until 1906.

Holmes is an expert at analyzing handwriting, as seen in “The Reigate Squire”, in which he identifies the murderers from a handwritten note. At the time of its publication (1893), graphology was little known in Britain, and for many readers this would have been the first they had heard of it.

The use of photography to record known criminals dates back to the 1840s. In 1871, a law was passed in the UK requiring that anyone arrested for a crime must be photographed.

Fingerprints and datasets

One accurate early method of crime scene investigation (CSI) was the recognition of the unique genetic quality of fingerprints. In 1892, Argentinian police officer Juan Vucetich proved the guilt of a murderer from the bloody hand stains she had left at the scene of a murder that irrefutably confirmed her presence at the crime scene. The idea was taken up by various police agencies, such as in Calcutta, India, where the first fingerprint-recording bureau was set up in 1897 by Sir Edward Richard Henry. Although fingerprint recording for identification was rejected at first by London’s Metropolitan Police in 1886, the system was adopted by the New York Civil Service Commission in 1901 and, within a decade, had become recognized internationally as an essential tool in criminal identification and detection.

At the time that Conan Doyle began writing the Holmes stories, the accumulation of datasets such as criminal records, mugshots, and fingerprints was still in its infancy, although he included them in his works—for instance, the use of fingerprinting to help solve the mystery in “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder”. The problem of how this information would be managed and disseminated, however, was a challenge for the future.

Blood typing

The classifying of blood samples into types A, B, and O was first codified by Austrian biologist Karl Landsteiner (1868–1943) in 1900, but research in the area began in the 1870s. Identification of the fourth blood type, AB, was published in 1902. Conan Doyle would have been aware of these advances in forensic analysis, which served as narrative inspiration. For example, in the first Holmes tale, A Study in Scarlet, Holmes declares to Watson that he has successfully invented “the Sherlock Holmes’ test”—an “infallible test for blood stains,” old or new, which can result in identification of the criminal. The significance of this test is immense, as he tells a bewildered Watson, “Had this test been invented, there are hundreds of men now walking the earth who would long ago have paid the penalty of their crimes.”

"Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years."

Sherlock Holmes

A Study in Scarlet

Forensic pathology

The science of forensic pathology (determining the cause of death by studying a corpse) was clearly of interest to Conan Doyle. It was a rapidly developing science. The practitioners at the turn of the 19th century were usually referred to as “medical examiners” or “police surgeons.” During Conan Doyle’s (and Holmes’s) career there were a number of high-profile cases in Britain that involved the work of forensic pathologists, such as Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1877–1947), whose work and analysis brought many notorious murderers to the gallows, including Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen.

DR. HAWLEY HARVEY CRIPPEN

The notorious case of wife-murderer Dr. Crippen combined a number of factors worthy of Holmes’s ingenuity. Dr. Crippen, an American homeopath, lived in London with his wife, Cora, but in 1908 began an affair with Ethel Le Neve. In January 1910, Cora disappeared, and in July Crippen and his lover fled, boarding a boat to Canada. Scotland Yard’s Inspector Dew ordered a further look at Crippen’s home, and human remains were found under the basement floor. Pathologist Bernard Spilsbury found traces of the toxic drug hyoscine in the remains, and identified some scar tissue as being consistent with an operation that Cora had undergone. Crippen and Ethel were arrested on arrival in Canada. Crippen was tried, found guilty, and hanged, while Ethel was acquitted. Forensic pathology played a key role in Crippen’s conviction. However, further DNA tests made a century on have confirmed that the remains were not Cora Crippen’s, and were of a male. His identity, whether Crippen killed him, and what happened to Cora, remain a mystery.

A taste for crime

From the beginning of the 19th century, there was a newsprint-buying public baying for sensational details of crimes. Conan Doyle not only fed this appetite, but also built on sociological theories such as those propounded by Gall, Beccaria, Lombroso, and others concerning the causes of crime. Conan Doyle was, after all, a doctor, and well aware of scholarly medical publications. He wrote the Holmes tales during a fascinating and rapidly developing period in criminology, which bridged the gap between the speculative and the scientifically based forensic pathology. As well as having a highly logical, analytical mind, Conan Doyle’s awareness of many theories and discoveries allowed him to keep ahead of the public’s knowledge, enabling him to constantly astound his audience with Holmes’s ingenuity.

Britain’s foremost forensic scientist and pioneering pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury performed thousands of autopsies on both murder victims and criminals.

JACK THE RIPPER

In 1888, London was shocked by the brutal serial murders of at least five East End prostitutes. Although forensic evidence was collected and examined, the techniques available to Scotland Yard at this time were basic, and forensic investigation was not an established procedure, so they focused on identifying and interviewing a large number of suspects. Police surgeon Dr. Thomas Bond used his knowledge of the victim autopsies to create one of the earliest “criminal profiles” of the murderer. Scotland Yard was reluctant to share details of its investigations with the press, since it was afraid of revealing its methods to the murderer himself. Faced with a lack of information, journalists resorted to sensationalized, speculative reports, and criticized the methods of the police force. This critical press, coupled with the unsolved murders, had a negative impact on the reputation of Scotland Yard. The murders remain unsolved to this day, but there are many theories as to the killer’s identity.