Villains have always existed in literature, appearing in the works of Homer and the Bible to Chaucer, Shakespeare, and beyond. Yet until relatively recently, it was either natural justice or fate that determined the villain’s eventual downfall—detectives, like Holmes, simply did not exist.

The origins of crime fiction

In the late 18th century, most European novels fell into two groups: social comedies and Gothic romances. It was from the latter genre that crime fiction eventually emerged. Early proponents of the form included the Marquis de Sade (1740–1814), who portrayed vicious criminals in the 1780s and 1790s with considerable relish, while Matthew Lewis wrote populist Gothic mysteries, such as The Monk (1796). Some novels, such as Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1782), even crossed the boundaries between these two categories. But while criminal activity features in all of these stories, there are no detectives to solve the crimes.

However, in the first half of the 19th century, crime writing began to move in a different direction. The US poet, critic, and novelist Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) and his French contemporaries Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), Victor Hugo (1802–1885), Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870), and Émile Gaboriau (1832–1873) defined the concept of the dogged detective and criminologist within their stories, establishing the crime writing style for which Conan Doyle would later become famous.

By the mid- to late 19th century, naturalist writers—who believed that both genes and social factors determined personality—were examining the criminal condition. Notable works include the French author Émile Zola’s novel about the eponymous domestic murderess Thérèse Raquin (1867) and Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866), which explored the mind of a psychopath.

Twenty years later, Conan Doyle invented Holmes, who arguably has had the greatest long-term impact and influence.

"It is, I admit, mere imagination, but how often is imagination the mother of truth?"

Sherlock Holmes

The Valley of Fear

Jean-Pierre Fossard, regarded as one of the great Parisian criminals, was captured by Eugène François Vidocq on December 31, 1813, while he was in charge of the Sûreté Nationale.

Holmes’s predecessors

In some ways, the roots of crime fiction started with the real-life career of one notorious Frenchman, Eugène François Vidocq. A direct inspiration for many French writers, from Balzac to Gaboriau, Vidocq was a petty criminal and spy who later channeled his skills in a lawful way when he established the secret Sûreté Nationale in Paris. In fact, Balzac became Vidocq’s close friend, using him as a model for the detectives in his novels, such as Le Père Goriot (1835), Illusions perdues (1837), and La Cousine Bette (1846). Balzac’s most famous detective was Jacques Collin, often known by his alias Vautrin. Dumas also worked elements of Vidocq’s activities into Les Mohicans de Paris (1854) in the form of the fictional Monsieur Jackal. And in Les Misérables (1862), Hugo based aspects of characters—like both the reformed criminal Jean Valjean and the relentless police inspector Javert who was pursuing him—on Vidocq’s astonishing career, which by then had been widely celebrated—however unreliably—in print and on stage. Émile Gaboriau even wrote about Vidocq’s adventures in popular novels including his Monsieur Lecoq series, published from 1866.

Vidocq’s fame also spread to the US, and Poe was apparently inspired by the French celebrity when he wrote what many believe to be the first pure detective story. Poe also used the terms “detection” and “ratiocination” (see The art of deduction) to describe the methods of his fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin—lateral thinking being a key feature of his crime solving. Indeed, Conan Doyle acknowledged that Poe’s stories were a model for later crime fiction, saying that three stories involving Dupin in particular provided “a root from which a whole literature has developed.” The first of these tales, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) is a model of the “locked room” mystery, in which a crime—usually murder—is committed under seemingly impossible conditions. In the second tale, “The Mystery of Marie Roget” (1842), which is based on an actual murder case in New York, Dupin has to reconstruct the last days of a mysterious victim’s life. The third story called “The Purloined Letter” (1844) combines a psychological duel between the detective and a blackmailer with the “hidden in plain sight” problem. Most of these foreign writers were read in Britain and influenced the development of the genre that was to become one of the most important strands in popular publishing.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870) was the most popular writer in Victorian England, and a master of suspense. Like many authors of the period, he wrote novels for serialization in magazines.

"Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?"

Arthur Conan Doyle

Poe Centennial Dinner (1909)

British crime mysteries

The first major British crime fiction writer was Wilkie Collins (1824–1889), who wrote The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868), which were published around two decades before Conan Doyle introduced Holmes. Today, they remain superb examples of mysteries and conspiracies unravelled by inventive detection. Like many novels of the period, these were first published in serial form.

The giant of the English serial novel, Charles Dickens (1812–1870) also experimented with mystery stories, drawing elements of the developing genre into his novels such as Oliver Twist (1838) and Our Mutual Friend (1865). Two of his most notable detective stories were Bleak House (1853), with Inspector Bucket, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870)—which remained unfinished at his death—featuring an early amateur private detective, Dick Datchery.

Writing around the same time was Irish author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814–1873), who created Gothic mystery novels featuring magic and the supernatural. But he also wrote novels that contained elements of a classic detective mystery, including Wylder’s Hand (1864), The Wyvern Mystery (1869), and In a Glass Darkly (1872), which purported to be the memoirs of an “occult” detective, Dr. Hesselius.

Edgar Allan Poe’s 1841 story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was later published in this 1893 collection that included “The Mystery of Marie Roget.”

The arrival of Holmes

In 1887, Conan Doyle published his first Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet. In this novel, he included forensics, detailed crime scene investigation, and careful character analysis. Once established as a key character in the Strand series, Holmes became a hit with an increasingly literate and enthusiastic reading public. It was therefore understandable that Conan Doyle’s decision to kill off his greatest fictional creation in 1893 met with public uproar. It seems that Conan Doyle had not realized the intense appeal of his stories. But even without Holmes, popular crime fiction was here to stay, and would continue well into the 20th and 21st century in its many permutations.

Holmes’s contemporaries

Apart from Holmes, there were other fictional detectives at this time who proved to be popular. The English detective Sexton Blake, described as the “poor man’s Sherlock Holmes,” was one of these. The first Blake adventures were syndicated in newspapers and magazines from 1893, and penned by a variety of authors. The first was “The Missing Millionaire,” by Harry Blyth. Like Holmes, Blake lived in Baker Street and had a tolerant landlady. Continuing until 1978 and adapted for stage, radio, and TV, there were over 4,000 Blake stories.

Another contemporary in crime fiction was G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936) who, in addition to writing the brilliant but murky police vs. anarchists thriller The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), created the unassuming Catholic ecclesiastical detective Father Brown. Brown solves problems using similar methods to Holmes, although, as a priest, he draws on his knowledge of the human condition through hearing confessions. Across five volumes of short stories written from 1911 to 1935, Brown became a staple of the British crime fiction diet.

There were other fine writers who wrote under the long shadow of Holmes. Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law, E.W. Hornung, introduced the gentleman thief/hero Raffles in The Amateur Cracksman (1899), and E.F. Bentley wrote the popular detective murder mystery Trent’s Last Case (1913), in which his gentleman detective Philip Trent falls in love with one of the suspects and comes to a number of incorrect conclusions.

Nicknamed “Penny Dreadful,” “The Union Jack” described itself as a “Library of high class fiction,” and serialized many tales. This cover from 1900 features detective Sexton Blake.

"All men thirst to confess their crimes more than tired beasts thirst for water."

G.K. Chesterton

The Illustrated London News (1908)

Crime-writing subgenres

Around the beginning of the 20th century, crime fiction could be divided into three main subgenres. There were stories about sleuths—as embodied by Holmes; pulp-crime fiction; and spy thrillers, often involving conspiracies . There was a huge dividing line between the type of detective mystery that Conan Doyle espoused, and what later became the more popular strands of sensationalist cliff-hangers typified by the latter two styles.

The British “Golden Age”

The period between the two World Wars became known as the “Golden Age” of detective fiction. Modelled on the Holmes tales, stories from this era tend to take the form of classic murder mysteries, or “whodunits,” featuring amateur detectives outsmarting the police, often in British upper-class settings. Agatha Christie was undoubtedly the most successful and well-known “Golden Age” author, but there were many others.

These included Dorothy L. Sayers with her Lord Peter Wimsey stories, the first being Whose Body (1923); Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion tales, which began with The Crime at Black Dudley (1929); Ngaio Marsh’s Inspector Alleyn mysteries, such as A Man Lay Dead (1934); and Leslie Charteris’s Simon Templar stories, which were later made into a popular film and TV series, The Saint. Introduced in 1928, Templar was an amateur detective/knight living slightly outside the law, with an instinct for detection and righteousness.

John Dickson Carr (1906–1977) was another writer of detective fiction. Although American, he set most of his novels in England, where he lived for many years, so his works are often categorized as British crime fiction. His detectives include the decadent and charming but untidy Dr. Gideon Fell (possibly based on G. K. Chesterton), and the aristocratic Sir Henry Merrivale. The Hollow Man (1935), which was called The Three Coffins in the US, includes a chapter-long textbook lecture by Fell about his methodology for solving apparently impossible crimes. Carr also wrote an early biography of Conan Doyle.

Edgar Wallace (1875–1932), the highly prolific English writer—who also spent time in the US as a successful screenwriter—created a crime-writing phenomenon almost single-handedly. At his height, in the 1920s, he was selling more than a million books per year. His main works include The Four Just Men (1905), The Green Archer (1923), and the J.G. Reeder stories (collected in 1925).

"Very few detective stories baffle me nowadays, but Mr. Carr’s always do."

Agatha Christie

Crime writer (1890–1976)

The detective fiction queen

The queen of 20th-century detective fiction was Agatha Christie (1890–1976). She is rated as the world’s best-selling novelist, with her sales ranking just behind the Bible and Shakespeare, and her books have been translated into 103 languages.

Despite her high social status, her work was “middle brow,” and therefore she could appeal to the general public across the world. During a long career, she published 66 detective novels and 14 short stories, while also creating the world’s longest-running play, The Mousetrap (1952). Other noteworthy books include The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), which has been regularly nominated as the best crime novel ever written by The Crime Writers’ Association, while And Then There Were None (1939) has sold over 100 million copies.

Christie had an inventive mind and created two main detectives: the Holmes-like Belgian former professional detective, Hercule Poirot, and the amateur yet brilliant observer of human nature, Miss Jane Marple. Both detectives used an acute psychological analysis of the protagonists in each story, linked with a close observation of the available and often overlooked details of apparently insignificant evidence—a lesson learned from Holmes. Poirot was first seen in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), which also launched Christie’s career, and he went on to feature in 33 novels. Marple debuted in a short story in 1926, “The Tuesday Night Club,” and in novel form in The Murder at the Vicarage in 1930. She appeared in 11 further novels and more than 20 short stories. Like Chesterton’s Father Brown, she is a retiring and contemplative character who modestly delves her way into each mystery. Both Poirot and Marple feature in numerous films played by a variety of actors.

The Strand Magazine ran from 1891 to 1950, serializing many writers’ works. This cover from 1935 features Agatha Christie’s Belgian detective Hercule Poirot in “The Crime in Cabin 66.”

The “Golden Age” in the US

S.S. Van Dine’s (a pseudonym of Willard Huntingdon Wright, 1888–1939) aesthete and sleuth Philo Vance was among the first true champions in the US of the Holmesian approach to solving crimes. Van Dine introduced Vance after writing an exhaustive study of the genre, which led to The Benson Murder Case (1926) and 11 other masterful detective novels.

Cousins Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred Bennington Lee (1905–1971)—both aliases—invented Ellery Queen. A gifted investigator, and often presented as the “author” of his books, Queen was very popular after the publication of the first novel, The Roman Hat Mystery (1929). Today, Queen has become a brand, appearing as a character in magazines, and theatrical, TV, and film adaptations.

However, the clearest inheritor of Holmes’s cloak and deerstalker in the US is Rex Stout’s clever but sedentary detective, Nero Wolfe .

NERO WOLFE

One of the most improbable successors to the Holmes legacy in the US was Rex Stout’s (1886–1975) oversized character Nero Wolfe. A consultant private detective, Wolfe lives in a “brownstone” house in upper Manhattan, where he is attended by his chef, Fritz, and assistant, Archie Goodwin who, like Watson, acts as the narrator.

Wolfe appears unchanged (aged 56) in 33 novels and over 40 novellas. He analyses crime by shutting his eyes and becoming immersed in a mystery while digesting a gourmet meal and reclining in his specially strengthened chair. He rarely leaves his home, but solves cases by gathering information, interrogating both the police and suspects, and using pure deduction.

Wolfe’s background is a mystery. Some Sherlockians trace his roots to Eastern Europe; others believe that he is the illegitimate son of Irene Adler and Holmes. Like Holmes, Wolfe’s deductions draw on his vast knowledge and experience, and demand a suspension of disbelief.

The “hard-boiled” school

In the 1930s and 1940s, another style of crime writing emerged in the US. The novels were unsentimental, realistic, and gritty, with cynical antiheroes for detectives who were quite different from Holmes. The style became known as the “hard-boiled” school of detective fiction. Dashiell Hammett (1894–1961) and the Anglo-American writer Raymond Chandler (1888–1959) are considered to be the founders of “hard-boiled” crime fiction.

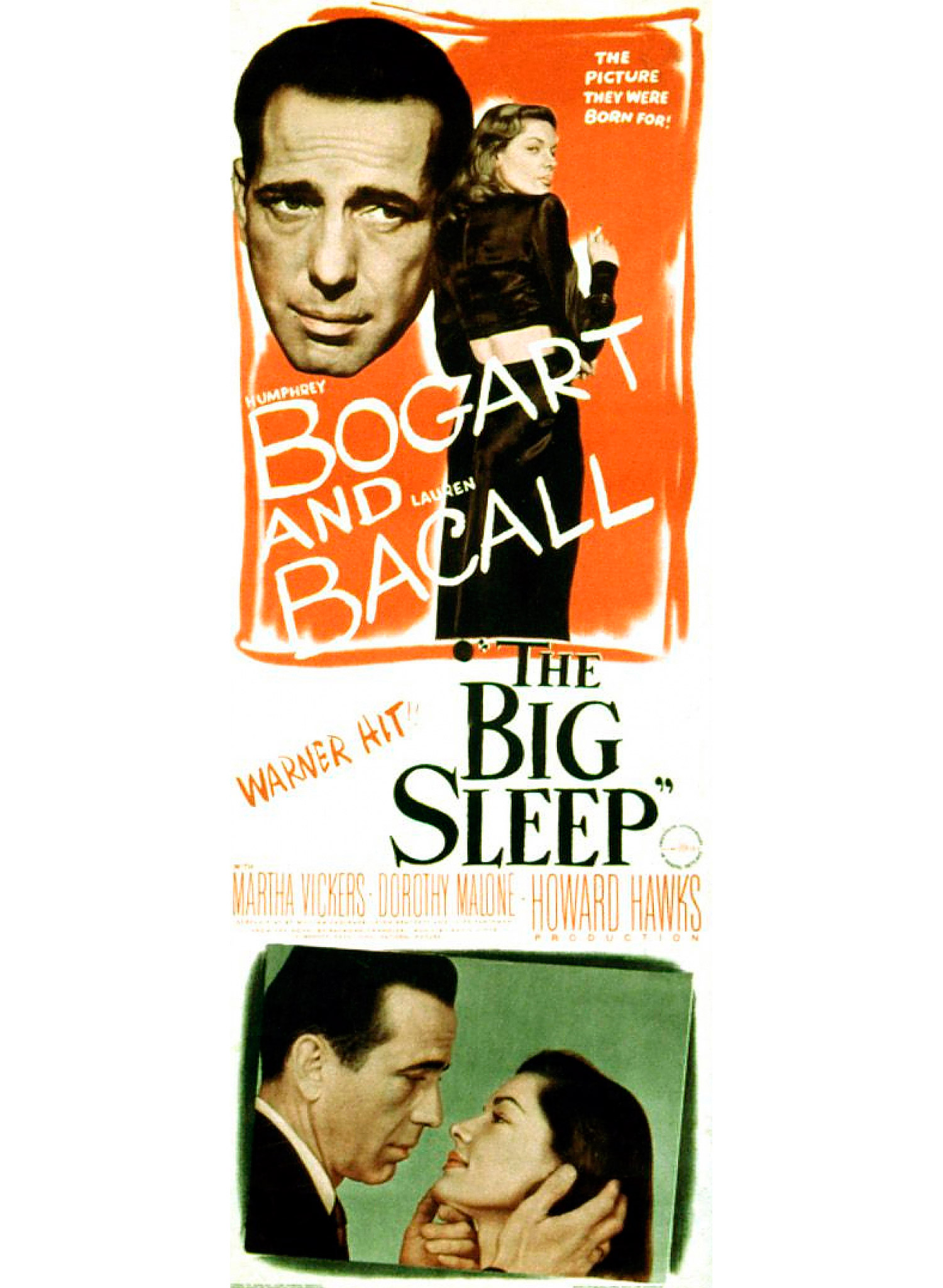

Hammett’s three leading protagonists—the unnamed “Continental Op” in Red Harvest (1929), Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930), and Nick Charles in The Thin Man (1934)—find themselves involved in mysteries that can be solved only by clever detective work. Raymond Chandler’s sleuth, Philip Marlowe, though, is less inventive, often merely following a track of bodies and glamorous femmes fatales to frequently inscrutable but violent conclusions, in works such as The Big Sleep (1939) and Farewell, My Lovely (1940).

The Adventures of Ellery Queen was made into four television series. The first season in 1950 starred Richard Hart. Lee Bowman (pictured) took over after the death of Hart in January 1951.

Holmes’s British legacy

Over a century after Holmes, the true legacy of Conan Doyle’s invention can be seen in a number of British crime fiction writers.

P.D. James (1920–2014) wrote ingenious and intellectually driven stories, often set in remote locations. She introduced her female private eye Cordelia Gray in An Unsuitable Job for a Woman (1972) and later published a series of novels featuring Commander Adam Dalgliesh, beginning with A Taste for Death (1986). With her wonderful prose, James’s crime fiction novels were soon considered to be works of serious literature.

Ruth Rendell (1930–2015), meanwhile, created a unique role for herself as an inventor of psychological crime narratives, also publishing under the name Barbara Vine. Her principal series of novels involve the carefully analytical Chief Inspector Wexford; this series began in 1964 with From Doon with Death and stretched over the course of 12 novels until 1983.

Colin Dexter (1930–) created the irascible Inspector Morse and his Watson-like companion, Lewis. Indeed, Dexter’s format is similar to Conan Doyle’s, as Lewis often carries out the legwork, while Morse solves the mystery. Beginning with Last Bus to Woodstock (1975) the series extended to 13 novels until 1999.

Ian Rankin (1960–) never thought of his books as genre fiction, yet his Detective Inspector Rebus series, which began with Knots and Crosses (1987) and has continued through a further 18 titles to date, has established him as one of the leading modern crime writers. Rebus is a likeably unlikeable character, who follows his instinct using a combination of Holmesian logic and Philip Marlowe’s strong-arm blundering.

Hinted at in Poe’s crime fiction, and made explicit with Holmes—from his bouts of depression to his reliance on drugs—many of these latter-day sleuths are also damaged by romantic or family issues, alcohol dependency, and secrets or ghosts from their past, among other things.

Humphrey Bogart famously played Chandler’s Philip Marlowe in the first film version of The Big Sleep in 1946. Lauren Bacall played Vivian Rutledge.

Contemporary crime fiction

The legacy of Holmes continues with crime fiction writers throughout the world, but particularly in the US.

The US crime writer John D. Macdonald (1916–1986) invented Travis McGee—a Florida boat-owning freelancer who takes on cases by which he is intrigued or outraged. The reader is placed in the role of the observer and forced to interpret what McGee is up to as he unravels cases. McGee collects evidence and thinks the problems through carefully, gradually drawing together the clues and, like Holmes, using them to trap his villains.

The American-Canadian Ross Macdonald (the pseudonym of Kenneth Millar, 1915–1983) wrote a series of adventures about the Californian private detective Lew Archer. Although he may employ some violent tactics, Archer nevertheless manages to perform some excellent detective work.

Much like Holmes was a pioneer of using science as a detective, the US author Patricia Cornwell (1956–) has excelled in describing modern forensics in stomach-churning detail. Her heroine Kay Scarpetta uses her mouth-watering cookery skills to examine mortal remains and confront evil criminals in novels such as The Body Farm (1994). Another American, Karin Slaughter (1971–), who debuted with her novel Blindsighted in 2001, also describes forensic investigations in gory detail.

Crime fiction is now a well-established genre, particularly in France, Spain, Russia, Japan, and Scandinavia, and numerous non-English-speaking authors like Stieg Larsson and Pierre Lemaitre are proving to be enormously popular worldwide. Whatever the authors’ origins or individual styles, there is no doubt that they have all gained from the legacy of Conan Doyle’s indomitable Sherlock Holmes.

Swedish writer Stieg Larsson (1954– 2004) planned this book as the first of ten, but only three were completed. The books were made into successful films.

EUGÈNE FRANÇOIS VIDOCQ

Born in Arras, France, to a middle-class family, Eugène François Vidocq (1775–1857) turned to crime as a teenager. He fought as a French soldier in several battles, where he killed at least two opponents. After a spell in prison for crimes that included forgery and assault, he became involved in spying.

Vidocq then transformed himself. Towards the end of 1811, he decided to use his experience of the criminal world to help the French authorities, establishing Sûreté Nationale, within the Prefecture of Police in Paris. Controversially, he recruited former lawbreakers, and even encouraged his agents to foster their contacts in the criminal underworld. He later resigned from the Sûreté and, in 1832, he founded the first private detective agency, Le Bureau des Renseignements. Vidocq was one of the first professional “criminologists,” combining his intelligence-gathering skills with forensic methods. He even kept card indexes of known criminals and how they operated, thereby creating an early version of a crime database.