[ 1 ]

The Six Minds of Experience

Surely it is the case that there are hundreds of cognitive processes happening every second in your brain. But to simplify to a level that might be more relevant to product and service design, I propose that we limit ourselves to a subset that we can realistically measure and influence.

What are these processes and what are their functions? Let’s use a concrete example to explain them. Consider the act of purchasing a chair suitable for your mid-century modern house. Perhaps you might be interested in a classic design from that period, like the Eames chair and ottoman shown in Figure 1-1. You are seeking to buy this online and browsing an ecommerce site.

Figure 1-1

Eames chair and ottoman

Vision, Attention, and Automaticity

As you first land on the furniture website to look for chairs, your attention and eyes might be drawn to the pictures to make sure you are on the right site. You might choose to look for the search option to type in “Eames chair.” You might also scan the page for words such as “furniture,” or for the word “chair,” from which you might look for the appropriate category of chair. If you don’t find “chair,” you might look for other words that might represent a category that includes chairs. Let’s suppose on scanning the options shown in Figure 1-2, you pick the “Living” option.

![]()

Figure 1-2

Navigation from Design Within Reach website

Wayfinding

Once you believe you’ve found a way into the site, the next task is to understand how to navigate its virtual space. While in the physical world we’ve learned the geography in and around our homes and how to get to some of our most frequented locations like our favorite grocery store or coffee shop, the virtual world may not always present our minds with the navigational cues that our brains are designed for—notably three-dimensional space.

Often it is the case that we aren’t sure where we are within a website, app, or virtual experience. Nor do we always know how to navigate a virtual space. On a web page you might think to click on a term, like “Living” in the example in Figure 1-2. But in other cases, like Snapchat or Instagram, many people over the age of 18 might struggle to understand how to get around by swiping, clicking, or even waving their phones. Understanding where you are in space (real or virtual) and how you can navigate through that space (moving in 3D, swiping or tapping on phones) are critical to a great experience.

Language

I find when I’m around interior designers, I start to wonder if they speak a different language than I do. The words defining a category can vary dramatically based on your level of expertise. If you are an interior design expert, you might masterfully navigate a furniture site because you know what distinguishes an egg chair, swan chair, diamond chair, and lounge chair. In contrast, if you are new to the world of interior design, you might need to Google all these names to figure out what they are talking about! To create a great experience, we must understand the words our audience uses and meet them at the appropriate level. Asking experts to simply look up the category “chair” (far too imprecise) is about as helpful as asking someone who isn’t a neuroscientist about the differences between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate gyrus (both of which are neuroanatomical areas).

Memory

As I navigate an ecommerce site, I also have expectations about how it works. For example, I might expect that such a site will have a search box (and search results), product category pages (chairs), product pages (a specific chair), and a checkout process. We have expectations for any number of concepts. We automatically build mental expectations about people, places, processes, and more. As product designers, we need to make sure we understand what our customers’ expectations are, and anticipate confusions that might arise if we deviate from those norms (e.g., think about how strange it felt the first time you left a Lyft or Uber or limousine without physically paying the driver).

Decision Making

Ultimately, you are seeking to accomplish your goals and make decisions. In this case you might be deciding if you should buy this chair (Figure 1-3). There are any number of questions that might go through your head as you make that decision. Would this look good in my living room? Can I afford it? Would it fit through the front door? At nearly $5,000, what happens if it is scratched or damaged during transit? Am I getting the best price? How should I maintain it? As product and service managers and designers, we need to think about all the steps along an individual customer’s mental journey and be ready to answer the questions that come up along the way.

Figure 1-3

Product detail page from Design Within Reach

Emotion

While we may like to think we can be like Spock from Star Trek and make decisions completely logically, it has been well documented that a myriad of emotions affect both our experience and our thinking. Perhaps as you look at this chair you are thinking about how your friends would be impressed, or how it might show your

status and that you’ve “made it.” Or perhaps you’re thinking “How

pretentious!” or “$5,000 for a chair—how am I going to pay for that, rent, and food?!” and starting to panic. Identifying underlying emotions and deep-seated beliefs is critical to building a successful experience.

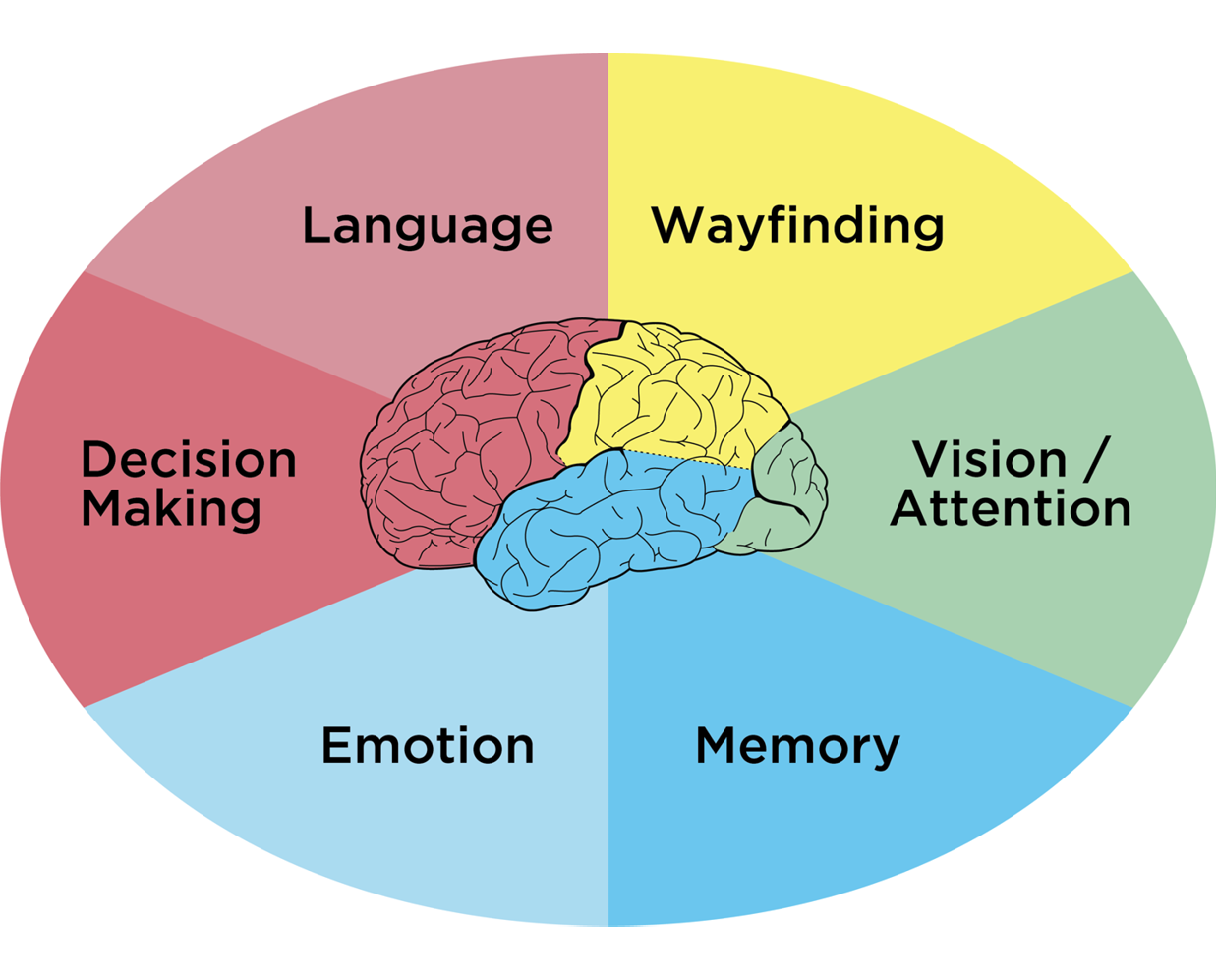

The Six Minds

Together, the very different processes described in preceding sections (shown in Figure 1-4), which are generally located in unique brain areas, come together to create what each of us perceive as a singular experience. While my fellow cognitive neuropsychologists would quickly agree that this is an oversimplification of both human anatomy and processes, there are some reasonable overarching themes that make this a level at which we can connect product design and neuroscience.

Figure 1-4

Six Minds of Experience

I think we all might agree that “an experience” is not singular at all, but rather is multidimensional, nuanced, and composed of many brain processes and representations. The customer experience doesn’t happen on a screen, it happens in the mind.

Activity

Let me recommend you take a brief pause in your reading and go to an ecommerce website—ideally, one that you’ve rarely used—and search for books on the topic of “customer experience.” When you do, do so in a new and self-aware state:

Vision/Attention

Where did your eyes travel to first on the site? What were you looking for (e.g., images, colors, words)?

Wayfinding

Did you know where you were on the site and how to navigate it? Were you ever uncertain? Why?

Language

What words were you looking for? Did you experience terms you didn’t understand, or were the categories ever too general?

Memory

How were your expectations about how the site would work confirmed or violated?

Decision Making

What were the microdecisions you made along the way as you sought to accomplish your goal of purchasing a book?

Emotion

What concerns did you have? What might stop you from making a purchase (e.g., security, trust)?

Now that you have some sense of the mental representations you need to be aware of, you may ask: How do I, as a product manager, not a psychologist, determine where someone is looking and what they are looking for? How do I know what my product audience’s expectations are? How can I expose deep-seated emotions? We’ll get there in Part II of the book, but for right now I want to agree on what we mean by vision/attention, wayfinding, memory, language, emotion, and decision making. I want you to know more about each of these so you can recognize these processes “in the wild” as you observe and interview your customers.