Putting it all together: the Lean roadmap to transformation

The objective of this chapter is to synthesise the book into a generic roadmap for organisational transformation. Some steps are referenced back to earlier chapters in the book and other concepts are introduced or repeated to reinforce their value.

Introduction

While every business embarking on the Lean journey will have different challenges based on its particular set of circumstances, there are several established key steps that can help you reduce resistance, spread the learning, and build the type of commitment and engagement necessary for Lean to thrive. That said, there is no single prescription for Lean transformation. The journey must be planned and initiated based on your own organisation’s unique needs, cultural maturity, opportunities and pressing issues. For example, if your company is about to go under, the bleeding of cash must be stopped first. In this instance the Lean roadmap would be very much focused on rapid cost reduction and aggressive application of methods such as kaizen events (see Chapter 6). The building of a Lean culture in this instance would come after the bleeding has stopped and the threat of extinction has been averted. However, to build sustainable transformation for the long term there are many elements that need to be fused together. Hence it is useful to provide a generic roadmap that can be used as the initial map for you to design and plan your journey towards the True North concepts of perfection in quality, cost, delivery and employee engagement.

GENERIC ROADMAP

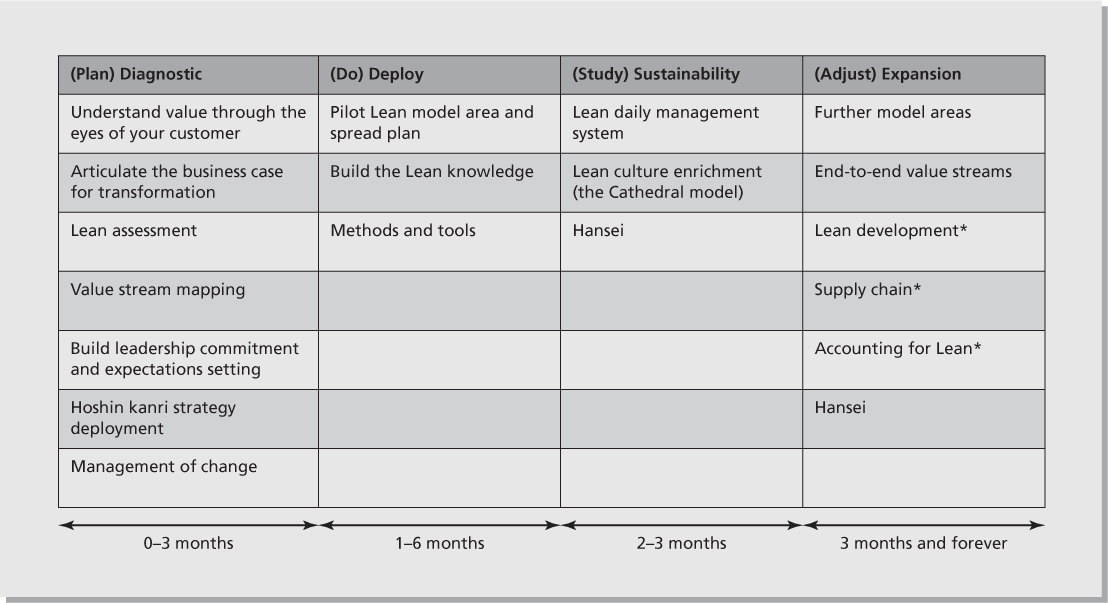

It is good practice to structure the Lean journey as a macro level PDSA cycle with multiple smaller PDSA cycles within this larger cycle. The large-scale cycle has the following components:

- Plan: includes the roadmap and diagnostic methods such as hoshin kanri, the Lean assessment, and value stream mapping.

- Do: is making the improvements through practice of the methods and tools.

- Study: is the creation of a learning organisation, one example is the application of the Lean daily management system.

- Adjust: is spreading successful changes, building sustainability, and identifying the next layer of improvement opportunity.

A generic Lean roadmap is shown in Figure 13.1.

1. Understand value through the eyes of your customers

An essential starting point for your Lean journey is to gain a deep appreciation of the value that your products or services deliver to your customers. We can be the leanest organisation in our business sector and still not survive if our customers do not derive value from our offerings. Customers buy outcomes, not products or services. We must know who our customer is and they can be either internal (the next person to receive the result of our work) or external (the end user). The Kano model shown in Figure 13.2 is really useful to initiate a dialogue and increase your understanding of what your customer defines as value.

The model was developed by Dr Kano in Japan while he was researching customer requirements for the airline industry. As illustrated in Figure 13.2, the horizontal axis represents the level of fulfilment regarding a given customer want. This ranges from not fulfilled at all on the left side to complete fulfilment on the right side. The vertical axis represents the level of customer satisfaction ranging from complete dissatisfaction at the bottom to complete delight at the top. There is an area around the centre of the model where the customer is insensitive; it is depicted in the figure as a neutral zone of indifference.

Figure 13.1 Generic Lean roadmap

*Detailed coverage of Lean development, supply chain and accounting for Lean are beyond the scope of this book. A brief overview of each is provided in the glossary and further reading sources are identified in this chapter’s references where you can learn more.

Figure 13.2 Kano model

Source: adapted from Dr Noriaki Kano,1 reproduced with permission of the Asian Productivity Organisation

Must be needs are a given and an example would be a clean hotel room. These needs are normally unspoken and their presence will not provide increased satisfaction, however their absence will result in extreme dissatisfaction. Performance needs are normally spoken and the motto is, ‘More is better’. One example would be internet access in your hotel room. Delighters are normally unspoken and provide an unexpected positive experience or excitement for your customer. An example of a Delighter in a hotel room would be free, cooled champagne in a sterling silver ice bucket and hand-made chocolates in your room on arrival. It is important to recognise that value is dynamic; it changes over time. What was once a Delighter, might now be a Performance need, and some time in the future may well become a Must be need. Perhaps in many parts of the world free internet access in your hotel room has descended down the ranks from being a Delighter five years ago towards being a Must be unspoken need today.

You should grasp how your current product or service fits against the Kano model and what the opportunities to differentiate your business from the competition are. This will highlight if you are providing what customers value – and some more! This exercise can turbo charge the results of Lean transformation from both a cost saving perspective and enhanced revenue generation.

2. Articulate the business case for Lean transformation

It is useful to use both push and pull messages to convey the business case for change. A push message articulates the risk and concerns of continuing to operate as we currently do. A pull message paints a picture of the opportunities and benefits that will be realised through the adoption of Lean.

Management understanding and belief that Lean will directly address core business problems is fundamental. Without this there is no business case for Lean and with no business case there is no compelling reason to change. The business case creates the ‘Why?’ for transformation. Crafting the business case at the True North metrics of quality, people growth and engagement, delivery and cost helps to frame the opportunity. Some example questions for developing the ‘What do we want to achieve from Lean transformation?’ include:

- Can we gain 10% market share by achieving half the industry average of customer complaints? (Quality)

- Can we increase employee engagement to the level that our employee turnover costs are half those of our nearest competitor? (Engagement)

- Can we increase revenue by halving our lead time? (Delivery)

- Can we decrease costs by 20% through eliminating waste and exploiting the capacity that is released through this waste elimination? (Cost)

An important factor to consider is that you must ensure that improvements realised through Lean translate to the bottom line financials. Otherwise we have claimed savings that are illusory. You have to take advantage of the improvements, ranging from improved employee capability to released capacity from waste elimination. To translate the improvements to the bottom line requires further work. This can take many forms including growing the business or developing the capability to do more with the same resources of people, space and equipment. The business case for Lean can and should alter over time as industry conditions change. For example, if you have released capacity in the system, a natural follow-on step might be to transform your business development and new product/service processes to make them more effective at winning new business to exploit these capacity savings.

3. Lean assessment

(See the template in the Appendix.)

A Lean assessment is a series of Lean criteria that identifies areas of opportunity for improving the performance of your business. The outcome should be a gap analysis of the current condition of the organisation versus the desired ideals of True North. This will then serve as key data for the hoshin kanri strategy deployment workshop. The Lean assessment should not be a one-off exercise; frequent assessments (every six months is common) help to track progress and indeed slippage, providing input into where focus is needed.

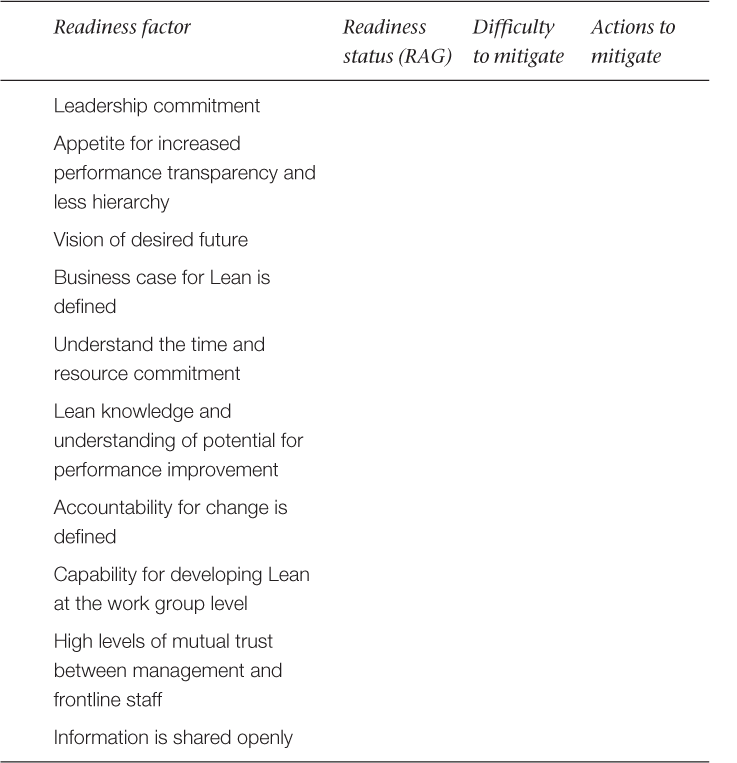

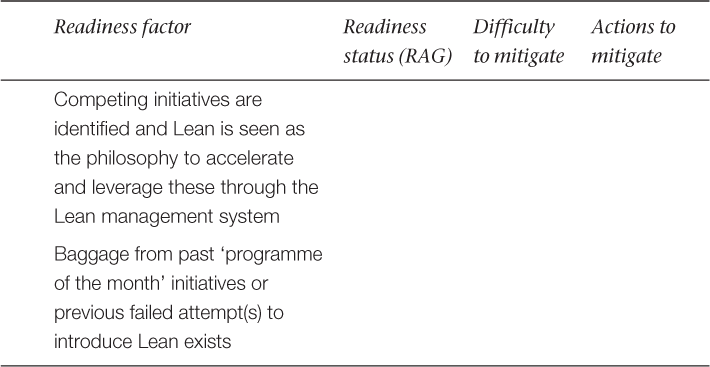

Your leadership team must also gain an appreciation for organisational readiness for Lean transformation and the current capability and skills of your frontline people. A further powerful diagnostic tool to gauge both the appetite for change and probability of success is a management change readiness assessment shown in Table 13.1. (Note: RAG is the acronym for red, amber or green status.) Red and amber items are prioritised under the ‘Difficulty to mitigate’ heading and then actions are taken to alleviate these factors.

4. Value stream mapping

Value stream mapping (VSM) is a visual method of showing both the physical and information flows in an end-to-end system or sub-system. The VSM shows on one page or zone an ‘x-ray’ of the business that diagnoses waste and process obstacles at a glance to the trained eye. See Chapter 3 for the value stream methodology and discussion on:

- current state (as is baseline including capacity and demand analysis)

- ideal state (True North vision to release attachment to the status quo and build tension for change)

- future state (realistic medium-term target).

Value stream mapping will provide guidance as to what are the highest leverage points in the system and where would be a good place to start the initial Lean pilot (discussed later in this chapter).

As the Lean transformation matures and expands beyond the initial pilot model areas, management needs to consider how to restructure the organisation by key value streams as identified by the product/service matrix (discussed in Chapter 3) and to have one person accountable for the total end-to-end flow of value. This is an extensive departure from the traditional practice of structuring organisations by department or centres of expertise. The organisation by value stream is in alignment with customer needs (customers flow horizontally) through your organisation. The traditional practice of the vertical organisation arrangement by department (pull out your business management hierarchy tree – it flows downwards and your customers flow across!) impedes the flow of value to customers.

5. Build leadership commitment and set expectations

‘Why should we care about Lean?’ Engaging and building alignment through a shared understanding and vision for the Lean journey is the basis for successful transformation. The senior leadership team needs to be deeply committed and singing from the same hymn sheet in order to lead by example. The paragraph below is a great analogy to show your management team the power of alignment:

‘Aligned geese will fly thousands of miles in a perfect V formation – and therein lies the secret: as each bird moves its great wings, it creates an uplift for the bird following. Formation flying is 70% more efficient than flying alone. At a distance, the flock appears to be guided by a single leader. The lead bird does in fact guide the formation, winging smoothly and confidently through the oncoming elements. If the lead bird tires, however, it rotates back into formation and another bird moves quickly to the point position. Leadership is willingly shared, and each bird knows exactly where the entire group is headed.’

Anon.

Initiative fatigue is another potential blockage to securing management commitment. Is the prevailing perception in your organisation that Lean will go out as quickly as it came in? How is Lean different? Lean differentiates from other improvement approaches in that it takes a holistic stakeholder approach to transformation. Simultaneous and congruent improvement in quality, employee engagement, delivery and cost is possible. Demonstrating these multi-faceted benefits and the positive business case helps to convince management how high the bar can be raised. This helps to dissolve the occasional unfounded belief that Lean is an expense and not an investment.

‘The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.’

Michelangelo

It is also effective to build tension for a better way by defining the ideal state versus the current state and then working backwards to a realistic, medium-term, future state vision. It is common to witness management sitting in a fool’s paradise thinking everything is great but the ideal state vision often provides a major jolt to this attitude. The management team need to have a firm grasp of current reality and a frank distaste of being there. Hence it is advantageous to have the diagnostic work completed prior to selling Lean to the senior leadership to take the leap to Lean management (better still if it does not need to be sold, i.e. the CEO drives the change agenda). In essence Lean needs to evolve into a non-negotiable moral obligation to continuously improve the business for the gain of all stakeholders.

A further beneficial tactic during this phase is to invite a CEO from an organisation that has successfully transformed its business through Lean to speak to your management team. This in the author’s experience invariably leads to a study tour of this exemplar organisation. Book study clubs are another very popular concept used for engaging leadership. For example, a certain chapter of a book is read between meetings and at the next get-together team members discuss the issues raised and take away concepts and lessons to test in their areas.

The Lean change agent must not mince their words regarding the degree of change that is required. A deep commitment to both cultural and technical change is necessary. The Lean methods are relatively straightforward and actually uplifting to roll out. However, keeping the new practices and behaviours in place and continuously improving is an entirely different challenge. This is when the human side of change or cultural adjustment is central. The management of change is discussed later in this chapter.

The transition to Lean management means managing in a very different manner than your organisation currently does. This requires a paradigm shift in how managers currently run their businesses. At the simplest level, a paradigm in business is the collective way of thinking that we have as a group. Management must deliver a top-down directive that Lean is the new way of running the business. Lean is as much about transforming thinking as it is about transforming processes. Table 13.2 lists attitudes that are engrained in many pre-Lean organisations on the left-hand side. To accomplish transformation requires that managers’ attitudes should transition towards the new paradigm on the right-hand side of the table.

Table 13.2 Paradigm shifts

| Old paradigm | New paradigm | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge is power | Involvement of all employees and visual transparency of information and metrics is power | |

| Command and control – management makes all the decisions and knows best how to run the business | Lead as if you have no power – by example and open-ended questions. You can’t lead if you can’t teach, and you can’t teach if you aren’t willing to learn. Build trust through deploying decision making down to the level where the work is performed | |

| Power and prestige are important | Influencing skills and coaching are important: true power is continuous learning and this begins with humility | |

| Manage from the office | Get out of the office and manage from the gemba to stay in touch and support people in a collaborative manner | |

| Keep employees busy at all times | Produce only what is needed to the rhythm of the end user demand | |

| Avoid mistakes | Welcome problems and learn from mistakes through testing controlled experiments |

Linking the Lean transformation to the delivery of the business strategy helps to convince the senior management team that Lean is not a superficial bolt-on of tools that are nice to try when you get some spare time. Lean is a complete management system for transforming the performance of the business, but it is not a magic bullet solution. When the planning and buy-in phases are completed it boils down to hard work and commitment to a new way of thinking and working. Managers must perform some soul searching to decide if they are ready for this commitment. They must also be willing to let go of hierarchy and having the majority of control for decision making, and be comfortable with increased levels of performance transparency.

One of the most powerful tactics to turn sceptics into believers is to get them directly involved through participation in kaizen events in the early days of your Lean transformation. Lean is learned by doing and the power of its philosophy is only fully experienced during these intensive, accelerated, improvement events.

‘Man’s mind, once stretched by a new idea, never regains its original dimensions.’

Oliver Wendell Holmes (US author and physician)

The development of a succinct elevator pitch2 on the benefits that Lean will bring to frontline employees, addressing factors such as improved job satisfaction, increased involvement and skills development, higher levels of trust, improved communication and a safer workplace, will serve leaders well for engaging people.

Finally, and far from least, please revisit the Lean daily management system described in Chapter 11. This is designed to facilitate leadership engagement and commitment on an ongoing basis.

A powerful exercise to perform with your entire senior management team at the early stages of the Lean transformation is to spend a few hours together (not as a formal hoshin kanri workshop but to gain accelerated consensus for the new direction) and write your operating philosophy and vision of where you collectively need to go on a flip chart. Then your entire team works to reach consensus on what the business stands for and how you are all going to deploy Lean to deliver this. End of story – the commitment is made!

6. Hoshin kanri strategy deployment

(Refer to Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion of this strategy deployment process.)

It is difficult to create a new culture if you do not know the results you need to achieve, so the first step is to define your desired future. This is where the hoshin kanri strategy deployment process provides clarity and facilitates alignment with your preferred future.

Hoshin kanri also addresses other prerequisites for enabling the success of Lean, it facilitates the building of alignment and consensus with the new direction at all levels of the organisation, it further moulds the business case for Lean, both for the near and medium term, and finally identifies how success will be measured and who is accountable. The eight steps discussed in detail in Chapter 2 are:

- Reflection on the previous year’s performance

- Review of the organisation’s vision, mission and values

- Objectives for the forthcoming year

- Alignment building and action plans

- X-matrix development

- Implementation

- Monthly evaluation

- Annual evaluation.

7. Management of the change plan

‘It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory.’

W. Edwards Deming

John Kotter3 identifies eight change implementation prerequisites; they are highly applicable to Lean transformation.

1. Creating a sense of urgency

Fear of change is genuine and usually unspoken. A compelling driver for change is often required. This could range from the loss of your main customer to the onset of a recession that threatens the business’s very survival. Leadership can create this sense of urgency by building the external story for change in advance of Lean transformation. This story would address such questions as:

- Why do we need to change?

- Why have we chosen Lean over other improvement philosophies?

- What will the transformation look like?

- What will each person’s role be in this transformation?

The true challenge is to overcome apathy and the wait and see attitude. You need to engage people’s hearts and minds, working on both the rational and emotional sides of the human psyche. A strong change story will place emphasis on the benefits that Lean can bring to all stakeholders – employees, customers, suppliers and the wider community – as well as to the business and its shareholders.

Focusing on what is wrong provokes blame and resistance. A more beneficial angle to take is to focus on the positive emotional benefits of the proposed change. Leadership communication should place emphasis on the positive changes that the transformation will bring to all stakeholders such as improved employee engagement as a result of more involvement in decision making and enhanced job security. People do not necessarily dislike change, they do not like to be changed, so involving them throughout the change process is a fruitful tactic. A good change management technique for addressing the concerns and highlighting the benefits of the change programme in your organisation is a stakeholder analysis. A stakeholder analysis (shown in Table 13.3) identifies the various stakeholders and what the change will mean for each of them along with the benefits and disadvantages. An action plan is then developed to address the concerns and augment the benefits. It is a great exercise to work through with the core Lean team to understand potential risks before widespread rollout of the communication process.

Table 13.3 Stakeholder blank document

| Stakeholder | What will change for this stakeholder group during the journey? | What will this stakeholder group view as a benefit of the Lean journey? | What will this stakeholder group view negatively? | How can we mitigate these concerns? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | ||||

| Customers | ||||

| Suppliers | ||||

| Community | ||||

| Organisation | ||||

| Shareholders |

2. Creating a change guiding coalition

A Lean promotion office (LPO) is commonly established to guide the Lean transformation. This group should be comprised of well respected people who have strong credibility and are trusted within the organisation. The team should have strong leadership capabilities and be represented by all stakeholders. This team’s key purpose will be to coordinate the Lean transformation and to navigate the inevitable challenges and roadblocks along the journey.

The role of the LPO includes:

- leadership alignment to True North metrics

- annual and monthly hoshin kanri adjustment reviews

- resource requirements for improvement (including workforce development and training)

- linkage between senior management and the frontline

- encouraging management to participate directly in improvement events as this is the richest form of learning (operational leaders should be driving education and execution of improvements in their areas)

- facilitating cultural transformation

- continuous communication

- prioritising improvement activities

- overseeing the Lean budget for training and other low-cost investments for 5S deployment, etc.

- monitoring progress and general reporting.

3. Developing a vision of the required company future state and a strategy to achieve it

An effective vision describes a clear picture of what the organisation will look like after a period of Lean transformation and it appeals to all stakeholders. It should be concise so as to provide guidance for daily decision making towards attainment of the vision, and adaptable to potential changes in the marketplace.

In the Lean rollout the hoshin kanri strategy deployment process described in Chapter 2 accomplishes this step.

4. Communicating the vision and strategy to the entire workforce (communication to all levels)

Many organisations under-communicate by a factor of 10 during change. People generally forget approximately 90% of what they hear after three days. Hence it advisable to err on the side of over- communication! People need to be immersed in the new direction that the business is moving towards. This should happen continuously and in multiple communication media such as one-to-one coaching dialogues with supervisions, emails, visual management storyboards and newsletters. The highest form of communication is leaders behaving and acting in a manner that is consistent with the aspired vision.

‘What you do speaks so loudly that I cannot hear what you say.’

5. Empowering people and removing barriers

Leadership must remove obstacles that impede improvement and release time and resources for Lean application. The frontline supervisors are accountable to senior management and must deliver the business objectives without alienating frontline staff who ultimately deliver customer value. These supervisors are fundamental to developing frontline people, leading the transformation and sustaining the gains. They require strong and continuous support from management to achieve the dual objective of delivering on customers’ requirements and releasing time for their frontline teams to drive continuous improvement. Metrics can be adapted or created to monitor this dual objective and also to capture how well supervisors are developing their people. Lean metrics are discussed in Chapters 1 and 11.

The target condition for a Lean supervisor is to spend their time in the following proportions: make the numbers 1/3, coaching 1/3, and improvement work 1/3.

A day in the life of …

… a typical Lean supervisor includes the following activities:

- facilitate the routine ‘make the numbers’ meetings

- lead by example using the Lean principles as guidance

- monthly employee one-to-one meetings and continuous application of the Cathedral model

- teach standard work to team members and update training records and visual display of these

- audit compliance to standard work and visual management

- coach people in systematic problem solving

- lead kaizen activities and roll out the Lean methods and tools as required

- nurture teamwork between departments

- skills assessment and cross training

- safety improvement

- daily and monthly reporting

- general administration: attendance and staffing issues, and coordination of countermeasures from identified deviations from target.

The people who most strongly resist Lean often tend to be the most experienced and respected employees and they generally do so with good intentions. The past success of the organisation was achieved by doing things a certain way, so changing how things are done jeopardises everything in their minds. We need to address this challenge through constructive feedback that addresses why the change is required and makes it clear that their support and changed behaviours and actions are critical to success. If people cannot buy in – and there are always a minority (a general rule of thumb is 3–4% of the organisation) – then they need to think about whether they should find another place to work. This is the hard reality but the factual side of conversion from a culture that no longer satisfies current and future business needs. The old adage ‘If you can’t change the person, change the person’ applies to these passive resistors. People will be given the information, coaching and time to make the leap, but some will be unwilling to jump on board. An analogy from the horticultural domain, ‘A few goats can very quickly undo the work of many gardeners’, explains why this tactic of removing active resistors is both necessary and in alignment with the ‘respect for people’ pillar. Not addressing this small minority can derail the entire journey and threaten the survival of the organisation and therefore the livelihoods of the majority who are willing to make the leap of faith.

6. Generating short-term wins

Early scores on the board through the attainment of quick visible wins is a great way to build momentum and get the flywheel of improvement turning. This provides the added advantage of positive feedback which helps to improve morale and also converts sceptics or those sitting on the fence into believers. The central challenge for leadership during this early phase, and indeed further afield, is to run the daily routine business of satisfying customers and then in parallel work on improving the business system. The wisdom of the capability trap discussed in Chapter 11 provides both motivation and guidance to overcome this challenge.

7. Consolidating gains and producing more change

Entropy (discussed in Chapter 5) is waiting in the long grass to pull down our improvement accomplishments at all times. The best countermeasure to entropy and sustainability challenges is to continue the process of neverending improvement and spreading of the changes to other value streams. Growing the problem-solving muscle in the organisation also helps to consolidate the gains and offset the eroding effect of entropy.

8. Anchoring new approaches in the culture

Lean practices need time and nurturing to take root, and it takes as much effort to keep them in place as it does to put them in place initially. This requires that leaders are developed within each work group who are capable of keeping the Lean culture going through their leader standard work, monitoring of the visual controls to drive accountability and the daily discipline required for success. Management produces order and consistency, leadership produces change and movement, and both are needed to sustain Lean.

8. Pilot the Lean model area and spread plan

Pilot areas are a deliberate approach to deploy Lean as an initial controlled test of change to prove the concept. They provide a focused and controlled playing field for experimenting and learning about Lean. This strategy of deployment is known as an inch-wide, mile-deep approach to change. Once the concept is proven the success and new skill capabilities can be leveraged and spread to other areas of the business organically. The tactic is to go narrow and deeply into a defined area (or a particular value stream) and intensively apply the Lean methods and the Cathedral model to build a showcase area, both technically and culturally. The pilot area can be kaizen event based (see Chapter 6) to accelerate the pace of change. The pilot area must be given active support from all support functions to nurture success and then be allowed the time to take root as the new way of working.

Additional benefits of a model area pilot approach to transformation include the following:

- It begins the Lean journey!

- It provides the physical evidence that Lean works and gives other areas of the business a ‘go see’ model.

- Immediate results and return on investment are achieved. If your organisation is not yet fully committed to Lean, it is extremely important to achieve some early wins to build momentum.

- It demonstrates how high the bar can be raised.

- Participants use the Lean learning model of ‘learn, apply and reflect’ to build internal improvement capability fast and to accelerate learning from the experience.

- It sways non-believers and helps to create wider organisational buy-in.

The selection of the pilot area is dependent on a number of factors:

- There is a compelling business need for change in the area.

- The area is a bottleneck as identified by value stream mapping (see Chapter 3).

- The area already has a high performance culture and strong leadership and is ripe for kaizen; the probability of success is high.

When you have achieved momentum, bedded down and are sustaining the changes, expand your scope to the entire value stream or other value streams as well as to support functions such as the office, design function, supply chain, etc. over time.

If the business is under intense pressure you can have numerous pilots in different areas at the same time. They may be at different levels of maturity, but they should all be steadily improving and learning from one another. You can also develop a redeployment plan for employees who have become available owing to productivity improvements in one pilot that moves them into another pilot area to help with its improvements.

The early proof point applications of Lean are primarily event based such as 5S rollouts and kaizen events to build knowledge. They are normally facilitated by an external improvement adviser. The focus is on fixing processes and demonstrating results. As the pilots widen and grow to include the end-to-end value streams they should be owned and led in large part by the area management. It is best practice if one manager is accountable for end-to-end flow in the value stream.

9. Build the Lean knowledge

Lean has evolved into a comprehensive management system; however various elements of the journey are counterintuitive. Hence the engagement of an experienced, external, Lean improvement adviser can be truly helpful in accelerating the journey and delivering real bottom line results faster.

Criteria for selecting a good improvement adviser

- Excellent people skills and the adviser’s chemistry suits the organisation’s current culture.

- A good influencer to get people to willingly change.

- Not agenda driven but customer and process focused.

- Strong business acumen – understands the financials and what it takes to exploit improvements to the bottom line.

- Solid expertise in Lean management and systems thinking, and a proven transformation track record with a generic but flexible roadmap to transformation.

- Appreciation of the purpose of the process rather than improving activity (e.g. improve the billing process or cash collection: payment is the purpose?).

- Is capable of adapting the transformation to your industry domain-specific needs.

- Ability to tackle cultural change and strong competency in change management and behavioural change.

- Robust facilitation and conflict resolution skills.

- Coaches rather than performs the improvements to build local ownership; develops internal capability and self-proficiency.

- Provides continuity of support after ‘events’ to nurture sustainability for a defined period.

10. Lean culture

A twin approach to cultural change accelerates the pace of improvement. The classic question of what comes first, the chicken or the egg, comes to mind. Does performance excellence drive a high-performance culture through the immersion in a workplace that demands compliance to high standards in behaviour and hence action? Or do we create excellent performance through culture change at the outset? There are varying viewpoints on which is the best approach, culture change first and Lean methods second, or vice versa? Both tactics have merit; hence the recommendation is to work on both in tandem. A good tactic to use in your organisation is to create an inch-wide, mile-deep Lean pilot showcase area (refer back to point 8 above) and also apply the Cathedral model (see Chapter 10) in this area. Leader standard work which is integrated into the Cathedral model is behavioural based and this is a potent tool for effecting cultural change and igniting people’s intrinsic motivation. It facilitates the refocusing of employee actions from performing a single function to the dual role of making the numbers and continuously improving. Add the Cathedral pillars of recognition, coaching and constructive feedback and you have a potent alloy for accelerating the transition to a Lean culture.

In a Lean culture all employees have an aligned and vivid understanding of the organisation’s purpose and the objectives it is working towards on the journey towards True North. People are comfortable at challenging the status quo and highlighting problems. Problems are not seen as embarrassing. Knowledge is shared openly through cascaded visual management systems and through multiple communication channels. Respect for people is evident in all the organisation’s undertakings, even at the expense of short-term business goals. Management appreciates that people are the engine of improvement and not a cost to be minimised. Hence people development is given equal priority to process improvement. In essence, a Lean culture transpires when people use disciplined thought and apply disciplined action using the structure of PDSA cycles.

The soft side of business transformation is the hard element. Changing people’s behaviour is a challenging but requisite step for Lean to take hold. This is often overlooked during Lean transformation and explains why the cultural aspect should be a critical consideration. The objective of developing a Lean culture is to enable people to think and subsequently act in a way that achieves superior results. The culture is centred on mentoring, facilitating, teaching and learning how to solve problems without delay, so they are not passed along to the next customer. Businesses need to decide what they need to stop doing (old limiting behaviours) and what they need to start doing (new empowering Behavioural Standards; see Figure 10.2 for details about Behavioural Standards). Successfully deployed, Behavioural Standards bring to life the Lean culture through new actions that are in alignment with the Lean philosophy. Your actions are always producing results – but they may not be the results you want!

Culture diagnostic questions

Questions to access and grasp the current state of your organisational culture include:

- How would you describe the organisation’s purpose based on its current priorities?

- To what extent does the mission of the organisation really inspire and guide behaviour?

- What department(s) has the most influence?

- What seems to be management’s most important consideration in general?

- How does decision making normally happen?

- What do employees care most about?

- Do employees deeply understand what their customers value?

- How do you currently execute important initiatives?

- What do you currently measure?

- How is success measured?

- How are problems perceived?

- Do employees hide problems through fear or embarrassment?

- Is the typical reaction to problems to find someone to blame?

- Is identifying problems damaging to career progression?

- Is Lean seen as a means to up-skilling and career advancement, or the opposite?

- Is there an environment of trust between management and employees, and between departments?

- How do we solve problems?

- Do the same problems keep recurring again and again?

- Is controlled risk taking encouraged?

- What happens when employees’ undertakings fail?

- How do we communicate with one another?

- Are employees comfortable with challenging management and highlighting breaches of acceptable conduct or Behavioural Standards?

- What is the approach to conflict when it arises?

- What criteria do we have for hiring new employees?

- How do people generally get promoted?

- How does one acquire influence and reputation?

- Do employees demonstrate teamwork and a spirit of collaboration?

- How do people act if they disagree with one another?

- What behaviours get recognised?

- What behaviours generate constructive feedback?

- Do people follow through on commitments?

- How are new ideas received?

To expose behavioural gaps that leadership needs to address you should compare the answers to the questions in the box against:

- the five Lean guiding principles of purpose, system, flow, people and perfection, discussed in Chapter 1

- the behaviours bullet points in the next box (and your own organisation’s Behavioural Standards developed through the Cathedral model in Chapter 10).

Pervasive in the creation of a Lean culture is the formation of a strong problem-solving system for making improvements and developing people. Problem solving is supported through standardised work (see Chapter 5). When people cannot adhere to the standard, problems will naturally be exposed through tightly linked Lean processes. This in turn demands that we must respond immediately to these issues or the process will cause chaos. The resolution of these problems is led by the actual team performing the work. The emphasis is placed firmly on solving problems at the root cause level, not just patching up the symptoms. This requires that people work through all stages of the systematic problem-solving process using multiple cycles of PDSA as required. Studying and adjusting, not just planning and doing, is a major facet of Lean cultural change. We are relatively competent at planning and doing tasks, but in general we are woefully inept at confirming our actions and drawing conclusions from them (studying and adjusting).

Behavioural changes

At a high level the behavioural changes required for a Lean culture need to shift from:

- a results only focus: achieve the results by whatever means possible

- silo-based thinking: concerned with islands of excellence or improving departments in isolation and without consideration of the overall system’s aim

- command and control: telling people what to do

- distrustful: intolerant of failures and blaming people when things go wrong

- a hierarchical focus: experts solve problems

towards:

- a process focus: appreciation that excellent processes are the means to great results

- systems thinking: the interaction and dependency of people, structures and processes

- leader teaches: go see the actual situation and develop and mentor teams in problem solving

- reflection and humility: the nurturing of a learning organisation through the use of PDSA cycles and controlled risk taking (and view failures as learning experiences)

- collaboration: everybody is involved in problem solving and improvement.

Sustained application of PDSA embeds new thinking patterns in employees and helps to build the Lean culture through its engrained philosophy of:

- truly question every process, bringing problems to the surface and carefully defining them, not just at the level of their symptoms

- understand the root cause(s)

- develop countermeasures that are viewed as interim until tested under a wide range of conditions and over a defined period of time

- plan the test of change on a small scale (or larger scale if the degree of belief is very strong that the change will be successful and the people in the area are receptive to the proposed change)

- closely monitor and study what is going on in the test

- learn from what happened and turn the lessons into the next PDSA cycle.

PDSA enables users to understand the complex interdependency of systems through structured testing and uncovering of the potential unintended consequences of changes. An example of an unintended consequence would be a purchasing agent sourcing a lower cost glove but during use the gloves were splitting and causing contamination to the company’s food products leading to increased levels of discarded items. Hence overall system cost was actually increased. Disciplined use of structured PDSA cycles would have greatly increased the probability of predicting this inadvertent effect.

Employees learn new technical and soft skills through real time, on-the-job training in the form of problem solving. Good Lean leaders create the environment for problem solving through continuous communication that problems occur because the system allows them to occur, not because people intentionally cause them. It is also emphasised that every problem is a learning opportunity and a productive concept, not a distraction from the ‘real’ work. When employees become comfortable with this paradigm and are not blamed when problems occur, a virtuous cycle of improvement begins to develop. Tapping into the problem-solving brainpower that your employees might otherwise keep to themselves drives performance excellence. A common side benefit is that when people start working on improvements, they have less to disapprove of and morale, by and large, improves.

11. Sustaining Lean

The work group are the only employees continually at the process. Hence the best sustaining system is a robust problem surfacing system. This requires that the capability is built within the work team to solve problems at the root cause(s) level on a daily basis. Chapters 11 and 12 provide an overview of this and numerous other practices for sustaining the gains.

12. Hansei

The Japanese term hansei translates as reflection and fits into both the study and adjust stages of PDSA. It is a form of constructive criticism and fosters the deep thinking required for Lean transformation.

‘Few people think more than two or three times a year. I've made an international reputation for myself by thinking once or twice a week.’

George Bernard Shaw (author and playwright)

The concept is about capturing and utilising lessons learned through reflecting on performance and initiating new ways to improve at all levels. Organisations often make the same mistakes repeatedly. A true learning organisation captures errors, determines their root cause(s) and puts in place effective countermeasures.

Hansei questions

Characteristic hansei questions include:

- What went well?

- What helped it to go well?

- What could we have done better?

- What hindered us from doing this better?

- What have we learned to enable a better performance next time?

Even when things go well hansei should be performed in order to look for ways to perform even better and, equally important, to understand what conditions existed that enabled success. In mature Lean organisations hansei is commonly performed daily at the individual employee level to reflect on the day’s performance and opportunities for improvement to do the job even better tomorrow. For hansei to take root the organisation must value and support it, release time for it, and measure it to ensure it is engrained into the daily work culture.

Review

Lean appears easy on the surface: ‘Sure, it’s just common sense’, you will commonly hear. However, if Lean were that easy, sustaining it would be a given and every company would be tremendously successful! This chapter details a generic roadmap to Lean transformation. The starting point is to understand what it is that your customers see as the value that your product or service delivers. Then the business case for Lean needs to be widely articulated to build a compelling reason for change. Detailed process diagnosis in the form of a Lean assessment and value stream mapping diagnose what we need to do differently to deliver the business case for Lean. Managers must be willing to change how they currently manage and be out there leading the transformation daily. Lean delivers the best results when it is integrated into the organisation to the degree that it is leveraged to deliver the business’s strategic objectives. Changing habits in your personal life is challenging; changing numerous people’s habits in an organisation is an even greater challenge. Hence a robust and continuous process for managing change needs to be diligently worked through. When the groundwork has being completed, it is time for action.

A pilot approach to deploying Lean is the author’s recommended approach. This will provide you with the philosophy for your company and foster learning through doing. In tandem with the technical changes, a Lean culture can be nurtured in this focus area to evolve Lean into a sustaining daily practice. You will experience surprises and mistakes along the way and that is fine as long as you learn from them and keep going. The hope for your business is that Lean will evolve into the management system that delivers your strategy and that the Lean mindset is woven into the collective thinking of your organisation.