Developing the Lean culture

Introduction

This chapter discusses the Cathedral model that is deployed to cultivate the development of a Lean culture. The model is a systematic framework for deploying the social behaviours that are required to bring the Lean culture to life.

A parable

Two bricklayers were working side by side. When asked, ‘What are you doing?’ the first bricklayer replied, ‘I’m laying bricks.’ The second bricklayer when asked the same question responded, ‘I’m building a Cathedral.’

This parable provides a powerful moral to management about the fortitude of employees driven by purpose and vision. Many leaders understand that the second bricklayer ‘sees the big picture’ but they miss the emotional significance, that the bricklayer’s work has a deeper meaning to him.

We are all building our own Cathedrals one brick at a time. To build a culture of sustained excellence you must understand the purpose and fulfilment that your people get from their work and become aware of their personal Cathedrals. This is their reason for getting up in the morning and the meaning they attribute to their work. Frank Devine’s Cathedral model discussed below is a systematic framework for creating and sustaining a culture of excellence and mass engagement of the workforce. Without these twin objectives your Lean transformation will not reach anything close to its potential for achieving excellence in business performance.

The Cathedral model

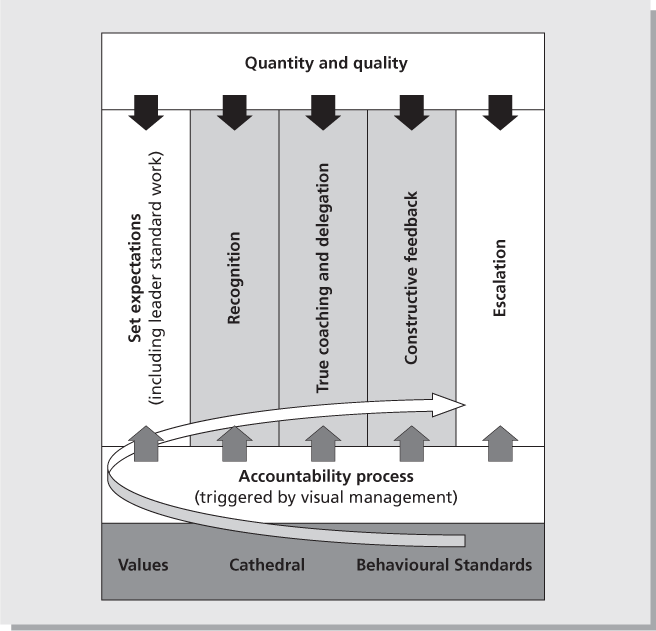

A study by Zenger–Miller of over 800 organisations involved in service improvement programmes concluded that ‘The majority of the problems were related to leadership, skills, strategy and people issues, and only a minority were related to the quality of the improvement methods and tools’.1 The Cathedral model (Figure 10.1) works on the psychological side of Lean transformation and is a powerful example of a practical and simple (but not easy) method that many academic authors2 have referred to as ‘socio-technical organisation design’. It is a framework that rigorously focuses on and then standardises the critical but few leadership social skills of setting expectations, recognition, coaching and constructive feedback. These are all built on and reinforced through a deep foundation of values and bottom-up Behavioural Standards. The Cathedral model is leveraged to increase the proportion of the workforce exhibiting inner-directed behaviour. Inner-directed behaviour means that you are guided by your own individual beliefs and values rather than external pressures to conform to the status quo. Working at the beliefs and values level of people gets to the root of influencing behavioural change. Employee owned Behaviour Standards (discussed later in this chapter) are the visible manifestation of this work. This in turn leads to higher levels of discretionary effort required to create and then sustain the Lean culture.

Figure 10.1 Cathedral model

The model’s foundation

The values, Cathedral concept, and bottom-up Behavioural Standards sit at the foundation of the model because they provide deep meaning, for individuals (Cathedral and individual values) and groups (Behavioural Standards) – see Figure 10.2. It is foundational: if your culture is not bedded down and rock solid further building blocks will descend into disorder through the rigours of time. The point is that many Lean attempts make little lasting change because the methods and tools will provide short-term, initial, quick wins. However, for retention of these gains and further progression, we need to work at the invisible social levels of the organisation. These concealed elements are the values that the organisation stands for, the personal meaning that the work epitomises for individual employees and the daily employee behaviours that drive the actions that deliver results. The values of an organisation refer to the collective standard of behaviour and ethics that the organisation stands for.

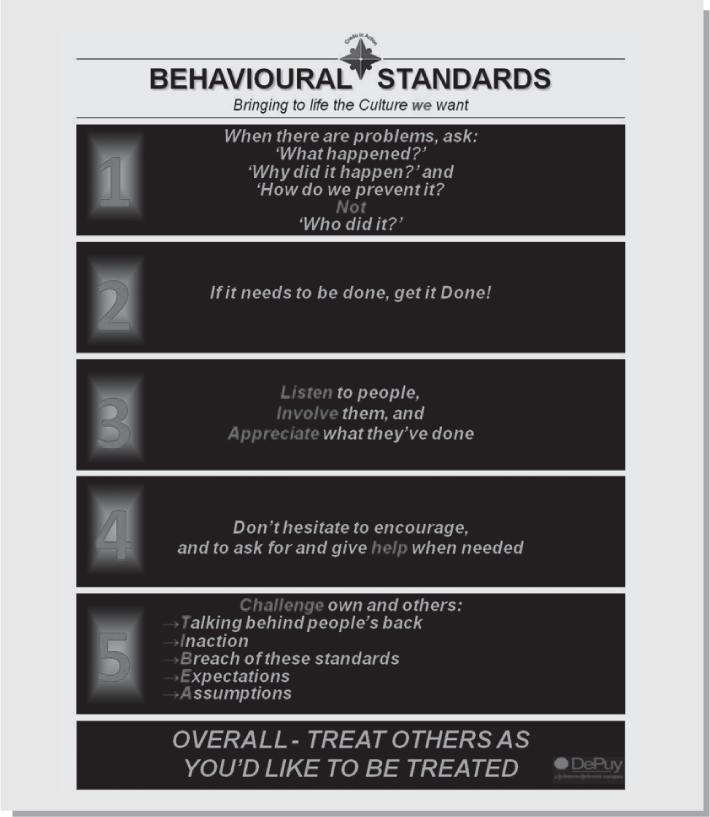

The reference to ‘Behavioural Standards’ in the model is to a process developed by Devine to overcome the problem of values being interpreted differently and thus losing credibility in the eyes of employees. His approach is to develop Behavioural Standards (see Figure 10.2) that are:

- measurable or binary (thus not subject to political interpretation)

- adaptable to local culture and style (thus not alienating and restrictive such as rules-based systems)

- developed by employees via mass joint decision making processes (not mere ‘consultation’ or ‘negotiation’)

- internally self-enforcing and thus more sustainable.

The use of stories (family narratives, etc.) helps people understand the underlying values of a particular situation and reinforces the resolve and spirit that unified Behavioural Standards bring to the table.

Figure 10.2 Behavioural Standards example

Source: DePuy Cork, Ireland. Reprinted with permission.

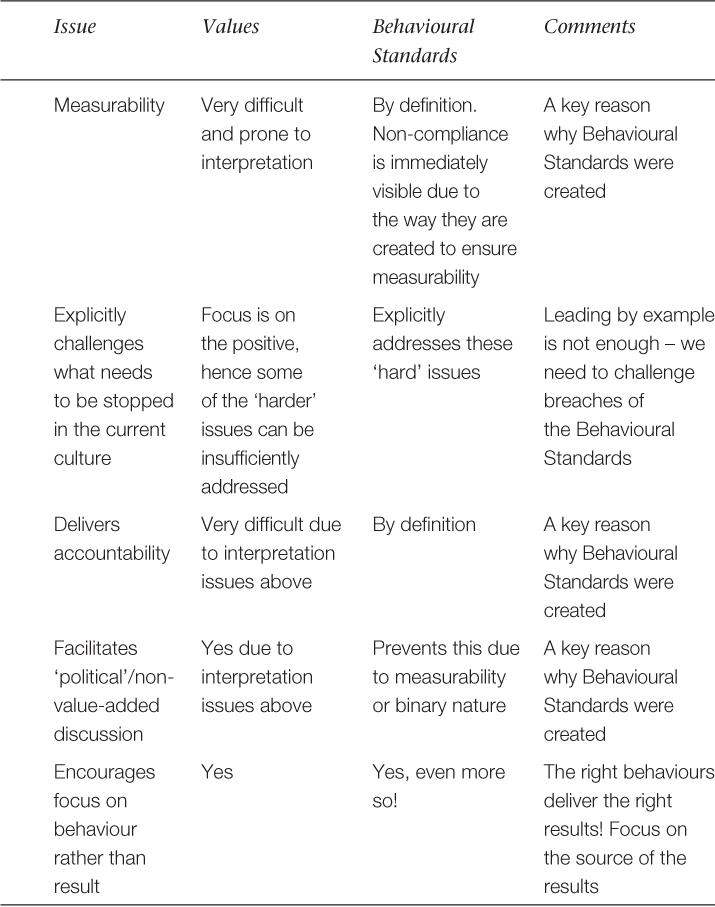

Table 10.1 outlines the limitations of using only values in your organisation and the enrichment that Behavioural Standards contribute to the cultural transformation.

Table 10.1 Comparison of Behavioural Standards and values

Source: Reproduced with permission from Accelerated Improvement Facilitators Training Programme

The Cathedral component in the model foundation sits at the level of the individual. This is the personal meaning and motivation that are attributed to the work and the organisation by individual employees. Remarkable employees are driven by something deeper and more personal than just the desire to do a good job – they are driven by their sense of ‘Cathedral’ or meaning. To foster the intrinsic motivation and discretionary efforts of your employees begin by asking the question, ‘What do each of us see as our own personal Cathedral for our job and the organisation that we work for?’ Obviously this will vary from individual to individual but a few collective themes usually emerge. Examples include providing for our families over the long term, sustaining the competitiveness of our company so as to keep local jobs, to ‘save lives’ rather than ‘to push people on trolleys’, and ‘I clean (hospital) rooms to prevent infections and hence I contribute to preserving life’. In summary, the purpose of the individual Cathedral aspect is about making work meaningful and helping employees to connect with the deeper purpose and contribution to society of their daily work.

Accountability process

The accountability process is the means of ensuring that the focus on process leads to actions for improvement. It is driven from comparing actual performance against expected performance. This is tracked in real time using the various visual management tools discussed in Section 2 of Chapter 4. Achievements as well as deviations from target are tracked by the people operating the process and the reasons for achieved and missed targets are recorded and used to drive higher quantity of recognition as well as to instigate problem solving to close the gaps. In Devine’s approach it is crucial to drive recognition not just problem solving. Leader standard work is the cement that keeps the Lean system together (this is discussed in detail in Chapter 11). It helps to create the structure and discipline necessary to ensure that daily problem solving is practised to close these gaps and continually raise the workplace standards. Leader standard work specifies what routines, recognition and coaching are to be widely practised to support the Lean culture. It also makes clear what we should not be doing, hence freeing up time for improvement work and people development. The accountability process appears at the foundational level in the Cathedral model because the repeated comparison between ‘what was expected’ and ‘what happened’ triggers a high quantity (see the top of the Cathedral model) and quality of conversations between the leader and employees.

Daily operation reviews are a central aspect of a Lean culture. These take the form of short, focused, stand-up meetings or huddles at the gemba. A synopsis of the previous shift’s performance is conducted and actions from the visual controls are reviewed for completion and effectiveness. This is the primary mechanism of driving accountability and longer-term actions are tracked using further visual tracking tools such as the accountability board (see Figure 11.1). The psychology of the visual controls is that it enforces the discipline to follow through on interruptions to the daily workflow at the stage when the root cause footprint is reasonably intact and hence they can be solved relatively quickly. This helps to shift the 100% focus on hitting the daily output numbers to a twin focus of making the output as well as on making improvements. This is in contrast to traditional work cultures: things that went wrong on the previous shift are frequently dropped, and hence the reoccurrence of problems is commonplace. Indeed visual mechanisms may be even more important in workplaces such as offices and engineering design companies where most of the work is invisible. Making the ‘invisible visible’ through visual tracking of projects, etc. builds disciplined implementation and speed of execution. A further benefit of enforced discipline is that it helps to change habits, which in turn leads to culture change.

A further accountability practice is the gemba walk (see the single point lesson on how to conduct a gemba walk in Figure 7.11). The purpose of the gemba walk is to see the value stream by crossing functional departments on the walk, to grasp the current situation, and ask why things are as they currently are. You also demonstrate respect to those doing the work through involving them in the walk and the resultant improvement actions. The accountability aspects of the walk include checking for adherence to standard work, A3 problem-solving activity and status, 5S maintenance, the status of metrics and the improvements that they are driving. Devine’s ‘managing on green’ concept is a key component of the gemba walk and it challenges ‘managing by exception’ (what Devine calls ‘managing on red’). It results in leaders constantly showing interest in, and recognising (thus driving up the quantity of recognition – see the top of the Cathedral model), what is going well in problem prevention before focusing on the ‘reds’. This means that there is a positive side to accountability. We need to recognise and appreciate employees for all the things that are going right. It is easy to forget that when things are going well it is almost certainly because someone has done something well and this should be recognised. Positive reinforcement of good behaviours that resulted in the attainment of green metrics will help to hard wire these behaviours into the new culture.

Set expectations

The first pillar of the Cathedral model is concerned with setting and making expectations explicit. The wise old saying, ‘You get what you expect’ is a powerful business concept. The rationale of setting expectations is to define the behaviours and actions that are required to sustain the gains and build a continuous improvement culture. The most powerful expectations are those that are mutually agreed between management and their teams. Leader standard work (see Chapter 11) is the instrument that is used to accomplish this in a Lean culture. Expectations should be set that are a challenge for the individual to achieve but are also not impractical or unreachable. Challenging people is a form of respect as it stimulates people to grow: they will generally raise their performance in response to a challenge.

The root cause of not meeting expectations in many instances can be attributed to the fact that they were never stated in the first place! Sitting your employees down to say what you expect from them seems so obvious, but we often assume that people know what we expect. The old adage that common sense is not so common is certainly true in this instance.

The Pygmalion, or Rosenthal, effect4 concludes that the greater the expectation imposed on people, the better they perform. For example, if one group of schoolchildren is continually told that mathematics is difficult and useless, and another group is continually told and shown that mathematics can be fun, is widely used and, like a computer game, is challenging and rewarding – the difference in eventual mathematical ability will be marked.

Recognition

Employee recognition is one of the most powerful forms of feedback that you can provide. Devine outlines a sequence whereby when a leader gives recognition to one of his team the recipient’s self-image increases which in turn raises their self-confidence. This places the person in a state of mind where their receptivity to coaching is extremely high, which in turn increases their capacity to absorb advice and learn, therefore leading to increased competence. Application of these new skills on the job to bed down the learning through practical use improves performance. This in turn provides the opportunity to provide further recognition, hence restarting the opportunity for a virtuous chain reaction of recognition. A true win–win engine of improvement begins to grow at an accelerated rate!

According to Alfie Kohn,5 only intrinsic rewards motivate over the medium and long term. Extrinsic rewards (for example monetary rewards) fade fast, become expected and may often lead to destructive behaviour. Intrinsic motivation is the natural desire that people have to do a good job and make a positive difference. It is the spiritual reward a person gets from making an improvement to their work.6 Intrinsic motivation is increased when people feel that they have an impact on the work that they perform. This is known as autonomy. As discussed in Chapter 6 intrinsic motivation is the difference between saying ‘You couldn’t pay me enough to do that’, and ‘I can’t believe I’m getting paid to do this!’ The bottom of the Cathedral model addresses the many individual and collective aspects of intrinsic motivation and places these into a system of improvement.

Cash has low-lasting impact value; research (refer to the study in Chapter 6, Section 1) points out that non-cash recognition delivers a 3:1 return on investment over direct cash rewards. Devine usefully distinguishes the effects of intangible recognition, tangible recognition (giving people things) and reward. His approach favours a reduction in emphasis on rewards and tangible recognition towards a focus on very high quality and quantity of intangible recognition within the context of the Cathedral model. The recognition has to be something that employees want, which is different in various areas of the world and also locally within the same work team. Lunch with the boss may be one person’s worst nightmare, another’s ultimate experience. People are motivated differently. Asking employees, ‘How do you like to receive recognition for a job well done?’ is thus a sound thing to do. Even if an employee doesn’t answer, you acquire loyalty points for taking the time to ask and showing an interest in the person.

For some, plaques belong on the mantelpiece; others would rather use them as firewood! Involving the recogniser and those involved in the design, implementation and measurement of the recognition process improves its effectiveness. If the answer to the ‘What do you want?’ question is money, the follow-up question ‘What would you use it for?’ may provide the true motivator.7

As long as the intended recognition has meaning to people it can make them do extraordinary things. Think what people will go through to win coveted sporting medals. How can you create that hunger for your company’s recognition symbols? Behavioural science validates that reinforced behaviours stick, which helps to explain how cultures develop, hence the power of focused and continual recognition for desired Lean behaviours.

Recognition suffers from a similar fate to improvement work, the mantra that we just don’t have time to do this! Not good enough. Time for planning recognition is a key aspect of leader standard work. Devine argues against allocating a time in leader standard work to actually give recognition but rather there should be a period, ideally at the beginning of each day, where the leader plans how they will integrate recognition into the natural flow of the day, thus not adding to their workload. The design intention is that opportunities for giving recognition are built into the daily work. For example, think about the route you took into work this morning, who you met, what behaviours you observed. What opportunities to give recognition to your people were there on your way to your desk during this brief period? We need to leverage where we already walk.

There are a number of considerations to be aware of when designing your recognition strategy. Quality recognition requires the trait of empathy – a desire to care for and help others. Fairness is a further critical component of recognition: if the same few are continually recognised and others are never acknowledged, your recognition endeavours can have the opposite intended effect than you set out to achieve. A perception of ‘pets’ can develop and this is damaging to effective teamwork. You need to be aware of how we treat our ‘go to’ people or employees who continually demonstrate discretionary effort. It is all too tempting to reward these people with even more work! If this continues indefinitely these people will either burn out or switch off due to being taken for granted. It can create a culture where poor performance is rewarded through being given less work and responsibilities.

Recognition should also not be just confined to successful outcomes. A required Lean behaviour is taking initiative and experimentation with new methods. These new methods can sometimes ‘fail’ to achieve the desired outcome. When we learn from these tests it leaves us in a stronger position to design a stronger test of change the next time. This is an opportunity to recognise the positive intent of the employee and their increased knowledge.

In the ‘setting expectations’ pillar you should establish criteria for what makes a person eligible for recognition. Anyone who meets the criteria is then recognised. Recognition should not however be dished out so ‘over-the-top’ that it becomes an entitlement. The danger here is that when it is not received it turns into a grievance. The way we deliver employee recognition is key to its effectiveness. Recognition should be specific about the exact behaviour, use straightforward language and state the positive impact of the person’s accomplishments.

True coaching and delegation

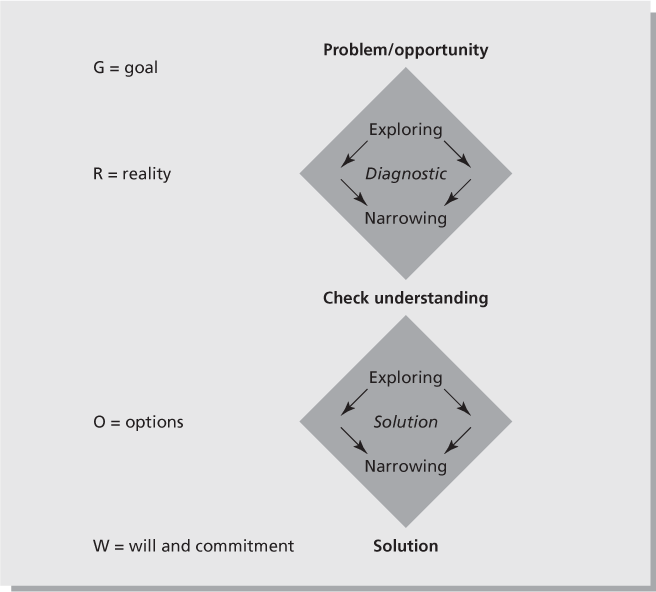

The intention of true coaching and delegation is to raise the capability of leaders within the organisation to perform technical processes such as problem solving, but more importantly to enhance critical standardised leader behaviours such as recognition, constructive feedback and coaching itself, to the extent where systematic excellence is achieved. Devine explains the Cathedral model approach to coaching as an integration of two streams of intellectual thought, the coaching stream and the problem-solving stream. A brief outline follows. (Note: the most commonly used coaching approach is GROW which is mapped onto the double-diamond in Figure 10.3. GROW does not integrate coaching and problem solving but is widely understood, especially in English-speaking countries.)

Figure 10.3 Double-diamond coaching model

Socrates was a Greek philosopher famous for his skill in developing himself and others through the use of probing open-ended questions. True coaching aims to achieve the best possible outcome and systematically avoids influencing except when the other person cannot make progress. You achieve results through questions and dialogue instead of orders, through active listening and support rather than controlling. You are encouraging a process of self-discovery. By really listening, you suspend judgement. While you actively listen, you are giving full attention to what the other person is saying and feeling. True coaching increases employees’ motivation to take initiative and to accept accountability. Hence the workload for the person coaching is reduced as they delegate work through tapping into the latent capacity for improvement that resides in their people. If a coaching session is blocked, it may be acceptable to seed the process by switching to the command role and suggesting an example of a solution. It is important however to remember that telling is our natural default style and we must try to resist this urge in coaching sessions.

Devine’s work has many parallels with the Toyota concept of kata. The kata concept is covered in detail in the excellent book by Mike Rother called Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness, and Superior Results. Kata translates loosely as developing routines or daily behaviour patterns – routines for making improvements and also routines for how to coach people to make improvements. These routines are similar to the Behavioural Standards described in the Cathedral model. The objective of both is to standardise the critical behaviours and build new habits that are required for a true learning organisation to take hold.

The continuous raising of problems makes the thresholds of our knowledge apparent. This requires that a combination of coaching and problem solving is called for. Both models use the scientific approach to coaching people. Devine’s double-diamond (see Figure 10.3) coaching model merges the HR stream of coaching with the problem-solving structure of A3 PDSA cycles. Rother also illustrates how Toyota uses succinct rapid coaching cycles of 15 minutes or less to deploy the improvement kata of asking the five questions posed in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2 Comparison of Toyota kata and the Cathedral model

| Kata coaching cycle for improvement | The Cathedral model |

| 1. What is the target condition? | Accountability process guides the conversations arising from visual management and leader standard work |

| 2. What is the actual condition now? | Visual management (target versus actual) and first diamond (diagnostic) of double-diamond coaching |

| 3. What obstacles are now preventing you from reaching the target condition? | First diamond emphasis on diagnosis and driving out assumptions and logical errors |

| 4. What is your next step (start of next PDSA cycle)? | Emphasis on immediate application of outcomes of the accountability process in the Cathedral model |

| 5. When can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step? | Standard daily start of shift reflection on ‘Where can I develop and strengthen the culture, where can I see opportunities to coach and give recognition, and reinforce the Behavioural Standards naturally today?’ Leverage where we walk (go see) on a daily basis and constant comparison of visual management actual v. target |

Both approaches place emphasis on the quality and quantity of conversations. The intention is not to hold ‘event’ type coaching, instead it is incorporated into the normal daily work via ‘little and often’ sessions that are indistinguishable from the daily work. Both approaches are light touch (assume good intentions), hard on the process and framed to develop people’s skills through the problem-solving and coaching processes.

Both kata and the Cathedral model recommend cost–benefit analysis for cost reduction only, not for decisions that will be required to move through obstacles on the way to the target condition. The approach is to use cost–benefit analysis but in a way that helps us reach the target condition, i.e. if the analysis reveals that a countermeasure is too costly, the next step is to determine how it can be done less expensively.

In essence both mindsets bring to life the invisible deeper thinking and counterintuitive mindsets that are so often the missing link in Lean transformations.

Constructive feedback

Constructive feedback is used when someone’s performance (or some aspect of their behaviour) is below the line of what is acceptable. It requires some upfront planning. Constructive feedback is not negative feedback; it is focused on the process and closing the divergence between expected and actual performance. Employees will react better to constructive feedback from you (it is specifically not criticism, the focus is on the situation) only after you have what Devine calls ‘earned the right’ through previously having taken the time to recognise and coach the person and focused on their development – you do not just come down on them at the first sign of a mistake.

(Note: accountability via visual controls triggers constructive feedback, when there is a gap in expected versus actual results. However, there is also a motivational flip side to accountability through ‘managing on green’; if people do meet and exceed their targets recognition is given.)

Escalation

Escalation is used in the event of a serious breach of conduct or if constructive feedback has failed to deliver results. Escalation can be formal or informal. An example of informal escalation is when we take an issue, jointly, to a different place (for example to a higher level to get it resolved).

Quantity and quality

The quantity and quality of deployment of the Cathedral model are paramount. The quantity facet denotes that the model elements are not standalone: it is a system. If we set expectations and do not provide recognition for excellent performance, it is highly probable that performance will degrade over time as employees perceive that they are being taken for granted. Similarly when employees do not know what is expected of them it is difficult to provide constructive feedback.

The quality component implies that we must deploy all the elements of the model in a world class manner. Systematic excellence is required; this means that each element must be developed and practised using first-rate standards.

Keeping in line with systems thinking, we note that both quantity and quality interact. There is no point in delivering the elements of the model in an exceptional way if we do not do it often enough. Likewise there is no point in developing expectations for a ‘select few’ when we are striving to develop a culture where everyone is a vital cog in a well oiled Lean machine. You have to keep practising the basics over and over to become excellent at anything in life, be that passing a ball in sport or recognising the achievements of your employees.

Review

Disciplined application of the Cathedral model is the catalyst to transform organisational culture to one of sustained operational excellence. The foundational elements of organisational values, employees’ personal Cathedrals and Behavioural Standards provide the fortification for a high-performance culture. The model also standardises critical leadership behaviours such as clarifying expectations, recognition, coaching, constructive feedback and escalation. These drive accountability for excellent performance into the fabric of the organisation. A key output of long-term use of the Cathedral model is heightened employee self-esteem. This is really important in an improvement culture that needs motivated and confident people taking daily initiative to improve their work. Employee inclusion in local improvement and decision making changes their beliefs and attitudes in a positive manner towards management and the organisation. It builds genuine trust. Think about how many things we take for granted every day that depend upon a system of trust. Whatever you do on the tools and methods side of Lean will be undermined by the individual’s self-esteem unless you take it into consideration. The countermeasure to this is deployment of the Cathedral model to develop the culture that fosters excellence.

The Cathedral model works as a system and hence it cannot function effectively in isolation (by practising sections in a standalone manner). The application of the model as a whole is greater than the sum of its parts. As an example, just using the recognition and coaching pillars of the model will not deliver the full potential of cultural enrichment possible or even the full potential of recognition or coaching, to sustain the Lean transformation.

Acknowledgement

This chapter is based on the work of Frank Devine. Frank developed the Cathedral model based on a synopsis of the best management practices. He specialises in accelerating the pace of culture change and the engagement of employees on the Lean transformation journey. He is also a visiting lecturer at Cardiff University where he specialises in the ‘getting buy-in’ aspects of Lean on the MSc in Lean Operations curriculum. He can be contacted at: [email protected] or see www.acceleratedimprovement.co.uk for case study examples of the results of applying the Cathedral model combined with mass employee engagement.