Lean management

What is Lean?

Lean is a way of collective thinking to methodically stamp out waste whilst simultaneously maximising value. It requires that employees transition from a singular focus on doing their daily work to a dual focus of doing their work and being motivated to performing their work even better, every day . This means that all employees need to think deeply about their work in order to understand the shortfalls and develop improved methods.

Why Lean?

Lean delivers a vast competitive edge over competitors who don’t use it at all or use it ineffectively. On the cost saving side (just one target of Lean), every £1 saved drops directly to the bottom line. The smaller your profit margins are, the greater the value of cost reduction. For example, if your organisation is operating in a market with a 3% profit margin, saving £150,000 would contribute to the bottom line the equivalent of bringing in an extra £5 million in revenue. That is assuming the extra revenue was produced 100% defect free first time! So, should Lean occupy a central position in your organisation’s boardroom and beyond? Lean improvement should be cost positive – no cost, low cost solutions – spend employee ideas and ingenuity not pounds!

Lean is so much more than cost reduction (we discuss True North metrics later in this chapter), it is a business strategy. Lean is also a culture change programme that progressively changes the thinking process of all your employees (hence it is known in Toyota as the thinking production system). This enables people to proactively improve their processes and products/services every day. Lean takes a balanced look at both the process and the people involved in the process, simultaneously bringing both bottom line impact and human growth.

There is widespread misunderstanding that Lean is just another round of traditional cost cutting with ‘headcount’ reduction as the primary target. However, this would violate the Lean pillar of ‘respect for people’ (discussed later in this chapter) and destroy lasting true Lean business transformation. The great majority of traditional cost-cutting exercises fail to categorise between the two forms of cost outlined below (value and waste). This is why cost cutting often ends up causing more harm than good in the long term. Traditional cost cutting is in effect cutting activity as opposed to improving the system and generally leads to an awful, destructive cycle in the long term.

Every organisation incurs two types of cost (both private and public):

- Costs that provide value to your customers. These costs are good and are to be encouraged if they bring competitive advantage and enhanced service. They result in value that people will pay for. An example of value that a customer buying a mobile phone would be willing to pay for is assembling the keypad into the plastic cover.

- Costs that are incurred, but don’t end up providing value to your customers. These costs are waste. Lean is about abolishing this waste to improve the ratio of good cost to bad. Most pre-Lean processes have a bad to good cost ratio of approximately 19:1. This means that for a process that, say, takes 20 minutes to perform, for every 1 minute we are providing value that the customer is willing to pay for, we are also delivering 19 minutes of non-value-added, or waste, that the customer is not willing to pay for. An example of waste that a customer buying a mobile phone would not be willing to pay for is searching for the keypad to attach it into the plastic cover.

Can you think about both categories of cost that are incurred in your organisation? What opportunities for improvement immediately spring to mind?

Lean strongly makes this distinction between waste and value. Eliminating waste would appear to be a no brainer, but much of the waste in our organisations is invisible. Value, on the other hand, is often much misunderstood and can also be non-obvious and unspoken. You need to ensure that your products/services are of value to the customer as a first step before striving to perform better.

‘There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently, that which should not be done at all.’

Peter Drucker (management writer and consultant)

This is where we need to merge Lean with an intimate appreciation of what our customers perceive as value.

Lean makes workplaces visible (anyone can quickly grasp how the area is performing in real time) so that abnormal conditions and problems are revealed as soon as they occur. A problem is any deviation between the target standard and the current actual situation. The Lean system is designed and supported so that these problems are countermeasured immediately and pursued until the root cause(s) has been dissolved. Lean frames problems as opportunities for improvement and for engaging the creative talents of your frontline people working their processes. Problems are opportunities because they identify thresholds in our current workplace knowledge. Traditionally, problems are viewed negatively and solved by ‘specialists’, or they are worked around. Worse still, problems are often concealed or brushed under the carpet. There are infinite problems, and opportunities to improve in all your processes; hence no problem is viewed in Lean as the biggest problem! How does your organisation currently view its problems?

‘No one has more trouble, than the person who claims to have no trouble.’ (Having no problems is the biggest problem of all.)

Taiichi Ohno1

The primary method for developing new improvement practices is the scientific method or PDSA (plan, do, study, act) cycle. Dr W. Deming finalised the PDSA cycle in 1993.2 Sustained application of PDSA embeds new cognitive patterns in employees and helps to build the Lean culture through its ingrained philosophy of:

- truly questioning every process – bringing problems to the surface and carefully defining them, not just at the level of their symptoms

- understanding the root cause(s) – there is often more than one root cause; causes can interact and stack up

- developing countermeasures that are viewed as interim until tested under a wide range of conditions and over a defined period of time

- planning the test of change on a small scale (or larger scale if the degree of belief is very strong that the change will be successful and that people affected are receptive to the proposed change)

- closely monitoring and studying what is going on in the test

- learning from what happened and turning the learning into the next PDSA cycle.

Brief history of Lean

The term ‘Lean’ was coined by John Krafcik, a MIT graduate, in an article published in 1988.3 The Machine that Changed the World4 was published in 1991 highlighting the great accomplishments of Toyota at NUMMI (a joint venture between Toyota and GM from 1984 to 2010) and the huge gap between Japanese quality and productivity and car manufacturers in the West.

The term gained widespread popularity when James Womack and Daniel Jones wrote the book Lean Thinking5 in 1996. However Lean history goes much further back; it is decades of accumulated wisdom. Lean uses many established tools and concepts along

with some newer ones to help organisations remove waste from their processes.

Lean history can be traced back to the late 1700s when possibly one of the oldest concepts of Lean was developed. Eli Whitney developed the principle of standardised parts to mass produce guns.6 In the late 1800s Frederick Taylor’s7 work on scientific management investigated workplace efficiencies and Frank Gilbreth looked at time and motion studies in the early 1900s.8 Both of these works influenced the design of the ground breaking assembly line by Henry Ford in 1910 when he started mass producing Ford Model

T cars.

Frank G. Woollard (1883–1957) made major contributions to progressive manufacturing management practices in the British automotive industry of the 1920s, and was also the first to develop automatic transfer machines while working at Morris Motors Ltd., Engines Branch, in Coventry, U.K. His work is highly relevant to contemporary Lean management, in that he understood the idea and practice of continuous improvement in a flow environment. Woollard also recognised that flow production will not work properly if used by management in a zero-sum (winner and loser) manner, and this shows he understood the importance of the ‘respect for people’ pillar in Lean management.

In 1941 the US Department of War introduced the ‘Training Within Industry’ programmes of job instruction, job methods, job relations, and programme development as ways to teach millions of workers in the wartime industries.

After World War II, Toyota started building cars in Japan. Company leaders Eiji Toyoda and Taiichi Ohno visited Ford to gain a deeper understanding of how Ford was managed in the US. Both were also inspired by Henry Ford’s book, Today and Tomorrow , 9 first published in 1926, in which the basic ideas of Lean manufacturing are presented. Toyota was also heavily influenced by the visits of Dr W. Edwards Deming who ran quality and productivity seminars in Japan after World War II and encouraged the Japanese to adopt systematic problem solving.

In the 1960s Shigeo Shingo (Toyota’s external consultant) developed the method of SMED and poka yoke (mistake proofing) and Professor Ishikawa at the University of Tokyo formulated the concept of quality circles which give employees far more involvement in the day-to-day running of their local workplaces.

The Toyota Production System (TPS) was developed between 1945 and 1970 and it is still being enhanced today. The growing gap in performance between Toyota and other Japanese companies in the 1970s attracted the interest of others and TPS began spreading rapidly within Japan.

In April 2001, Toyota Motor Corporation produced a document for internal use called ‘The Toyota Way 2001’.10 This 13-page document describes the distinctive aspects of Toyota’s culture which contributed to its success. The document was produced to help ensure a consistent understanding of the Toyota Way among all associates across the rapidly growing and increasingly global Toyota Motor Corporation.

Lean today

Lean has traditionally been called Lean Manufacturing. In the past 10 years the ‘Manufacturing’ has been widely omitted. Lean is now being adopted across all industries such as manufacturing, healthcare, government, financial services, construction, software, transactional processes, tourism, logistics, customer service, hotels and insurance. Since all work is a process, and all value is delivered as a result of a process, the application of Lean is applicable to all industries. The common denominator is people undertaking work.

Recent Toyota recall crisis

In 2010 Toyota recalled 5 million cars for suspected unintended acceleration. This has since transpired to be a defect in the use of the cars rather than in the vehicles themselves. A 2011 NASA report concluded that the unintended acceleration incidents were the result of floor mats being improperly installed on top of other floor mats, or driver error, and that there were no electronic flaws in the cars that would cause unintended acceleration.

That said, Toyota has reflected on the company’s strategic direction. Chief executive officer (CEO) Akio Toyoda testified in 2010 to the United States Congress that the company had erred by pursuing growth that exceeded ‘the speed at which we were able to develop our people and our organisation’, and Toyota would reinvigorate its traditional focus on ‘quality over quantity’.11 The company has come back stronger and sharper than ever before despite a dramatic downturn in sales in the global car industry due to the worldwide recession and the closer-to-home supplier and production disruption caused by the catastrophic Japanese tsunami in 2011.

True North Lean

‘True North’ refers to what we should do, not what we can do. It is a term used in the Lean lexicon to describe the ideal or state of perfection that your business should be continually striving towards. Lean is a journey without an absolute destination point, we will never achieve perfection. Opportunities for improvement never end, and it is only when we take the next step that we in fact see possible future steps. However, like a sailor we must be guided towards our shoreline. We look to True North metrics to guide us while knowing that we can never arrive at the True North; it is a concept not a goal. It is the persistent practice of daily improvement by all your employees to advance to True North that makes organisations first class.

True North metrics you can use in your business to achieve a balanced blend of success are:

1. People growth

- Safety (zero physical and psychological incidences)

- Job security (zero layoffs due to improvements, revenue growth)

- Challenge and engagement (number of problems solved)

- Coaching (one-to-one development sessions)

3. Delivery

- One piece flow on demand (cycle time, OEE (overall equipment effectiveness), changeover metrics, EPEI (every product every interval) – see later chapters

4. Cost

- 100% value-added steps (zero waste)

The five principles12

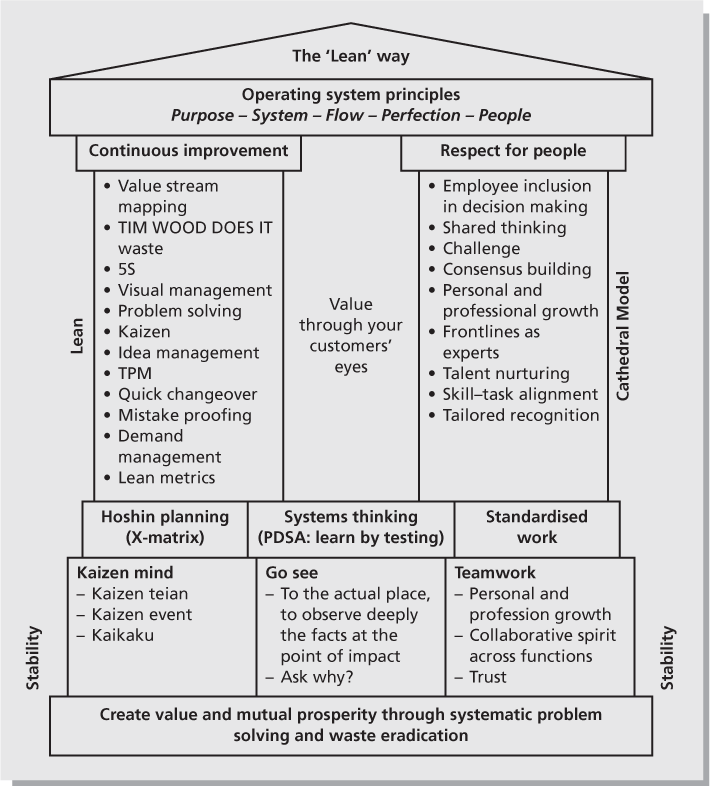

Lean is based on five principles (see Table 1.1 below). The principles are supported by two pillars called continuous improvement and respect for people. These pillars are discussed later in this chapter.

Table 1.1 The Lean principles

| Principle | Description |

| 1. Purpose | The purpose of all Lean activity is to enable an organisation to prosper. Organisations need to clearly define expectations of what they are trying to accomplish. This of course means different things at different levels in the organisation and these aims must be made explicit. It calls for a deep understanding and appreciation of our customers’ spoken and unspoken needs. Customers buy benefits not product features or services. What benefits do our products or services deliver? Step into the shoes of your customers. As John Bicheno13 states, ‘are we selling cosmetics or hope?’ Think about the purpose of your product/service range. |

| 2. System | A system can be broadly defined as a set of integrated and dependent elements that accomplishes a defined purpose. Organisations are systems, much like people, organic plants and the car you drive. They are more than the sum of their parts; they are complex, constantly changing over time and interacting. Improvement means change and hence making changes without an appreciation of the organisation as a system can have unintended consequences. Lean focuses on total system improvement rather than on isolated ‘islands of excellence’ |

| 3. Flow | Pre-Lean processes generally contain greater than 95% of steps that do not add value from the customer’s perspective. Hence the incredible potential for improvement in business performance across all sectors using Lean to analyse existing processes and reorganising for flow. Tackling the 3Ms: muda (waste), mura (variation), and muri (overburden) provide huge improvement leverage to build smooth work flow. |

| 4. Perfection | Lean is never fully implemented; it is truly a journey without an end point as the possibilities for improvement are endless. Perfection is the concept that we are striving for. It is the proactive advancement towards this ideal state that makes Lean organisations exceptional. There are always opportunities for improvement. Lean is like peeling an onion: as each layer of waste is exposed and dissolved at the root cause level, the next layer becomes visible. |

| 5. People | People are the true engine of Lean. The most successful Lean organisations thrive because they have intrinsically motivated people nurtured by the ‘respect for people’ pillar of Lean (discussed later in this chapter). They are actively engaged in daily problem solving to remove the sources of waste as made visible through the design of Lean systems. |

Best-in-class Lean organisations are meeting and exceeding their customers’ expectations using half of everything in comparison with traditionally managed organisations. That is half labour hours, half facility space, half capital investment, half on-hand inventory, half defects and half the number of adverse safety incidents. These results are not achieved overnight; they require a long-term commitment to improvement. If you work in an organisation with strong leadership you should be well on your way to gains of this magnitude within two to four years. Harnessing the ‘respect for people’ principle this impressive maximisation of resources can be achieved with greatly enhanced levels of employee inclusion and engagement than at the start of the Lean journey.

The Lean operating system

A Lean operating system (see Figure 1.1 below) is based on continuous improvement, respect for people and elimination of waste. The operating system integrates six elements:

- principles to drive aligned thinking and behaviour

- systems thinking to understand the interconnected areas and dependencies of the business

- Lean methods to make abnormal conditions stand out

- metrics to tell us how we are doing

- respect for people to keep the continuous improvement element balanced

- a foundation of constructive dissatisfaction with the current performance level, leadership engagement with the people doing the work, and a strong teamwork ethic.

First pillar: Continuous improvement

‘We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but habit.’

Aristotle

Continuous improvement is a way of life for Lean organisations. It is closely aligned with the principle of perfection – the recognition that there are always opportunities to improve your business. The word ‘continuous’ means just that, it is a commitment to everyday improvement, not a one-off burst of change activity. Entropy is at play in every workplace; this is the level of randomness in systems or the drift toward disintegration. This means that if we are not continuously improving every day we are in fact sliding backwards due to the deterioration effect of entropy. Everything essentially degrades over time. Hence this would suggest that Lean is not a nice to do (or when we get time), it is mandatory for long-term survival.

Figure 1.1 Lean operating system

One of the under-appreciated aspects of Lean is the immense compounding impact that small incremental improvements have over time. If everyone just improved their job 0.1% every day that adds up to a 25% improvement per person year on year. That equates to a colossal advantage in the fullness of time. You should think about how you can challenge and support your staff to improve their own work by even 0.5% every week, to achieve remarkable gains.

Lean systems are designed to make normally invisible small problems and non-conformances visible. Waste is made evident every day and there is pressure from the process – by way of design, tightly linked processes highlight problems – for people to fix problems in relative real time. The core purpose of all of the Lean methods discussed in Chapters 4 to 9 is to surface problems and opportunities for improvement.

The popular parable of the woodcutter captures well the intent of continuous improvement:

The woodcutter

A young man approached the foreman of a logging crew and asked for a job. ‘That depends,’ replied the foreman. ‘Let's see you chop down this tree.’ The young man stepped forward and skilfully chopped down a great tree. Impressed, the foreman exclaimed, ‘You can start on Monday.’ Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday rolled by – and Thursday afternoon the foreman approached the young man and said, ‘You can pick up your pay check on the way out today.’ Startled, the young man replied, ‘I thought you paid on Friday.’ ‘Normally we do,’ said the foreman. ‘But we're letting you go today because you've fallen behind. Our daily felling charts show that you’ve dropped from first place on Monday to last place today.’ ‘But I’m a hard worker,’ the young man objected. ‘I arrive first, leave last and even have worked through my coffee breaks!’ The foreman, sensing the young man’s integrity, thought for a minute and then asked, ‘Have you been sharpening your saw?’ The young man replied, ‘No sir, I've been working too hard to take time for that!’

Are there examples in your organisation where there is no time to ‘sharpen the saw’?

Second pillar: Respect for people

‘Respect a man, he will do the more.’

James Howell (historian, 1594–1666)

Lean is a voyage to developing outstanding and aligned people through involvement in continuous improvement. The focus is on eliminating waste, not making people redundant. It goes without saying that people are not waste, they are in fact the only organisational asset (properly led) that appreciates and becomes more valuable over time. To grow people who will continuously improve your organisation you need to engage their collective intelligence. The expert is the person nearest the actual job. This means that we must respect and nurture people’s talent and brainpower. It is management’s responsibility to champion excellence in thinking and to challenge people to do great things. A challenge generally brings out the best in people and inspires them to achieve greater levels of personal and professional performance.

Respect for people is not a motherhood and apple pie concept. It brings value and prosperity to a business. We respect people because we want employee engagement and their discretionary endeavours. The best methods and tools are worthless if people won’t engage with and practise them! Engaged employees are involved team players who strive to improve. They look for ways to implement and share ideas. All of the Lean methods, when deployed properly, exemplify respect for people. This is because seasoned Lean practitioners frame the methods and tools to both improve the process under study and develop the people using them. For example, standard work allows time for improvement and people development as there is less time spent fire fighting (wasteful work is disrespectful), which in turn leads to more engaged people. When engagement levels are high, turnover is low, which leads to higher productivity as there is less time spent training people to become competent in their job roles. A true virtuous cycle transpires.

Respect for people is not one dimensional; it must extend to all stakeholders, namely shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and the community within which we work.

All the categories of operational waste are known as muda (Japanese for waste) in Lean and they violate the pillar of ‘respect for people’. For example if you were to waste people’s time through making them wait for a meeting, it conveys the subtle message that your time is more valuable than theirs. Similarly, making defective products is disrespectful; it is a waste of physical and human resources and erodes an organisation’s competitiveness. Overburdening (muri) people and unevenness (mura) also violate this pillar. Examples of this that you see in many businesses are price promotions. They cause employees to work like crazy one week to meet an artificially created demand. But the next week they have little work to do because real end user demand generally stays relatively constant.

A waste walk, also referred to as a gemba walk (the actual place where the work is performed), is one of the Lean practices that demonstrates a strong sense of respect by management for the people adding value on the frontlines. Management walk the frontlines regularly to stay in touch with reality. To lead improvement they must be humble and spend more time at the frontlines where the real customer value-added work takes place. There is no substitute for seeing the actual facts (richer than data from the office) at the source. It sends the clear message to people that their work is important.

Respect for people also means:

- Clear roles and responsibilities are communicated and there is regular constructive feedback on performance (respect means that people know what is expected of them).

- The correct equipment is provided to perform the work (respect means that people have the resources to perform their jobs well).

- Individual strengths and talents of employees are known and utilised daily, tasks are aligned to people’s skill-sets (respect means that people get the opportunity to work on what they are qualified to do).

- Tailored recognition is given to people in a timely manner to nurture excellent performance (respect means that people are appreciated).

- Development opportunities are encouraged through participation in improvement teams and cross training (respect means that people are given the opportunity to grow and develop as individuals).

- There is a strong sense that the welfare of the organisation’s people matters through management’s actions (respect means that management’s actions are people centric).

- Ideas for improvement are expected as a normal part of the job and support is provided to put these into practice (respect means that people have input into improving their own work areas).

- The purpose of the organisation and its wider benefit to society are clearly articulated (respect means that people are led by purpose rather than being assigned tasks).

- The opportunity to perform high-quality work in a safe environment is provided (respect means that people can perform their work to a high standard without fear of danger).

- Regular opportunities are provided for people to interact socially both internally and at externally organised events (respect means that management recognises the social aspect of work and that loyalty between employees promotes teamwork).

Respect for people encourages employees to be self-reliant; to act as if they owned the business themselves. Instead of waiting to improve things, people are empowered to test changes and implement successful experiments. There is mutual trust that people will do the right thing for the business at all levels.

Problem solving is at the heart of Lean organisations and is one of the uppermost demonstrations of respect for people. The message to employees is that management can’t solve all the problems single-handedly.

Managers often get the wrong idea about the ‘respect for people’ pillar because they think it is fuzzy and not businesslike. In my experience the root cause of most Lean transformation failures can be traced back to not practising this pillar. Hence for Lean to succeed, the ‘respect for people’ pillar is mandatory.

‘He who wants a rose must respect the thorn.’

Anon

Hidden waste is robbing our profits

‘If the nut has 15 threads on it, it cannot be tightened unless it is turned 15 times. In reality, though, it is that last turn that tightens the bolt and the first one that loosens it. The remaining 14 turns are waste (motion).’

Shigeo Shingo (industrial engineer and thought leader)

The elimination of waste is integral to Lean, and there are three broad types of waste: muda, muri and mura. You need to hunt down all three of this triad to realise the full benefits of Lean.

Muda

The actual time spent adding value (often referred to as core touch time) to a product or service is tiny in comparison with the overall delivery lead time. The value-adding core touch time is often less than 5% of the overall lead time before the application of Lean. The travesty is that it is all too common in many organisations to have all their technical expertise focused on maximising these value-adding steps, for example making a machine cycle faster. The greater opportunity is to tackle operational waste. The remaining steps fall into value-added enabling (approximately 35% of pre-Lean process steps) and non-value-added (approximately 60% of pre-Lean process steps).

Value-added

For a step to be classified in this category it should satisfy all three of the following questions:

- Would the customer be willing to pay for this activity if they knew we were doing it?

- Does this step progress the product or service towards completion?

- Is it done right the first time?

Value-added enabling

These steps do not pass all three of the value-added questions above but are necessary to operate the business. However, the customer is unwilling to pay for them as they do not add direct value to your product or service (e.g. inspection, budget tracking).

Questions to determine if a process step is value-added enabling include:

- Is this step required by law or regulation?

- Does this step reduce the financial risk for the shareholders?

- Does this step support financial reporting obligations?

- Would the process fail if this step were removed?

It is important to recognise that these activities are really non-value-adding but you currently need to perform them. You need to strive to eliminate or at least reduce their cost.

Non-value-added

Lastly the pure waste category of process steps falls into one or other of the 13 waste types detailed in Table 1.2 below. Waste is not confined to the stuff that we throw in the bin! The acronym of TIM WOOD DOES IT is useful to help to commit these waste categories to memory and to build a culture where the shared way of employee thinking is to view their work through this common lens of waste identification. This is an extremely powerful lens to view your workplace processes through; the magnitude of the improvement potential becomes clear. It is important to state that the actual waste types are symptoms of deeper problems which must be rooted out. For example the waste of searching (motion waste) for something is perhaps a symptom of poor workplace organisation. Over-processing is generally considered one of the worst of all the waste categories as its occurrence generates many of the other wastes. Think about over-cooking your dinner and the waste that generates: defects (burnt food), inventory (wasted ingredients), motion (extra stubborn washing-up), energy (oven), waiting (call pizza delivery!), overhead (light on in kitchen), safety (smoke alarm), etc.

In reality all waste cannot be removed; it is a goal to aspire to. A world-class process would be considered as having a 25–30% value-added ratio (value-added time divided by overall lead time). Think about all the money and employee aggravation that these waste categories are draining from your organisation.

Table 1.2 Waste categories for the manufacturing and hospital domains

Muri

Muri is the excessive overburden of work inflicted on employees and equipment because of poor planning, organisation and badly designed work processes. It is pushing an employee or piece of equipment beyond the accepted limits. Unreasonable work is almost always a cause of variation, shortcuts and quality concerns.

One example of muri includes people working crazy long hours due to being overwhelmed with work. Removing muda or waste in this situation will help but may not be sufficient. Matching capacity to demand is one of the tactics to countermeasure the overburdening of people and equipment. Other examples of muri include:

Mura

Mura is the variation in the operation of a process and in the demand that is placed on your organisation. It is the unevenness and unbalanced exertion placed on people and machines. Variation is the enemy of Lean and creates many categories of the waste listed in Table 1.2. Not conforming to or absence of standardised work is a widespread cause of mura. Artificially created demand driven by organisational policies, etc. is also a major cause of mura. Other examples include:

- not following software development coding standards

- multiple physician surgery tray preferences

- food promotions causing demand spikes

- month end hockey stick effect – shipping everything on the last day of the month to make the financial numbers.

Review

The instinctive gut reaction that people get when they hear the word ‘Lean’ in organisations is fear about ruthless cost cutting and head count reduction. The term Lean can have a negative connotation and infer that the philosophy is a totally reductionist strategy. I have been involved in successful Lean journeys where the word ‘Lean’ was substituted by ‘operational excellence’ or the organisation’s own version (e.g. ‘The “X” production system’) where the ‘X’ refers to the organisation’s name. Continuous improvement merged with the ‘respect for people’ pillar is not about cutting value-added costs or people layoffs. It is about engaging the hands, hearts and minds of all employees to improve their workplace. It is about growing your business, securing jobs, saving taxpayers’ money in the public sector and saving thousands of preventable deaths in our hospitals through delivering better quality care at lower cost.