The Multi-Level Learning Coach 59

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

trying to avoid embarrassment or threat by placing demands on the other.

As touched upon in Chapter 1, Argyris (1995) describes organizational de-

fensive routines as “any action, policy, or practice that prevents organiza-

tional participants from experiencing embarrassment or threat and, at the

same time, prevents them from discovering the causes of the embarrass-

ment or threat” (pp. 20–22). Perhaps both managers thought that they did

not have the skills required to enable the project to succeed, and because

of their escalating con ict, they may have become even more invested in

“winning” by placing responsibility on the other party in order to avoid

personal failure.

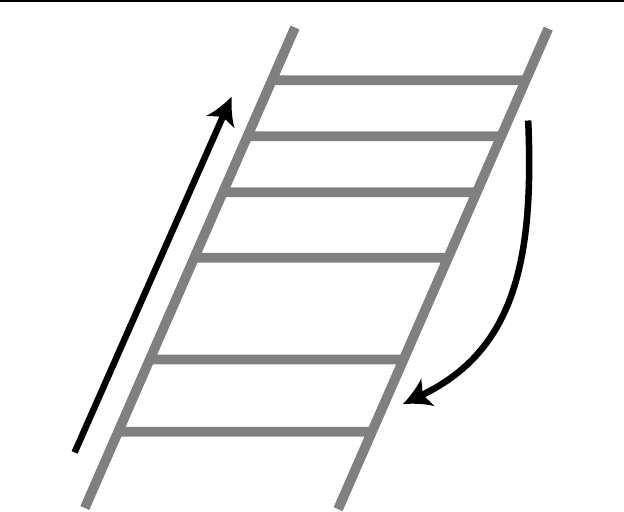

Because climbing the Ladder of Inference occurs in the minds of other

people, it’s impossible to know what Bernard and Tracy were thinking at

the time. However, what is known is that the project was delayed for weeks

because of this stalemate, and that this ultimately led to the project’s being

Select Data from

What’s Observed

Ascribe Meanings

to the Data Selected

(based on cultural and

personal experiences)

Make Assumptions Based on

the Meanings Added

Draw Conclusions

Adopt Beliefs About the World

Take Action

Observable

Data

Beliefs

filter

the data

selected

FIGURE 3.3

The Ladder of Inference [Adapted from Argyris (1990)]

60 Roles

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

cancelled by the CIO. Both managers were reassigned to roles with sig-

ni cantly less responsibility, which leads us to believe that their defensive

routines and poor communication led to less than optimal results both for

them and for their organization.

O’Neil and Marsick (2007) o er the TALK model, a straightforward

tool that multi- level learning coaches can use to help both themselves and

their clients communicate in ways that, rather than triggering defensive

routines, lead to interactions that are more consistent with the three core

values of facilitation. The model is a sequential approach to communicat-

ing, and it is an acronym for the four steps involved: Tell the person what

you are thinking from the start, ask whether he has the same interpreta-

tion of the situation, listen to his response, and keep open to others’ views.

Shared meaning, they say, can come only from accepting and bringing to

the surface our multiple understandings, those that represent the various

rungs on the Ladder of Inference.

Productive communication, as mentioned previously, underpins all the

elements of an e ective group process. An e ective approach to manag-

ing con ict, along with e ective communication, for example, might also

have helped Bernard and Tracy resolve their di erences. We will discuss

con ict management later in this chapter. We now turn to another impor-

tant component of group process, a model for group problem solving.

Problem Solving

Much of a team’s work is focused on problems. Problems in this context

are simply a gap between what is desired and what currently exists. The

central elements of problem solving are the following steps, which can be

seen both on a macro level (in project plans, for example) or on a micro

level (in meeting agendas focused on more speci c issues): Identify the

problem, collect data about the problem, analyze the data to determine

the root causes, develop possible solutions, select the most appropriate

solution, implement the solution, and evaluate and monitor the situation

after implementation. Project methodologies such as Six Sigma, TQM,

and other quality improvement approaches build these steps directly into

project plans in order to generate sustainable improvements that focus

not just on symptoms, but on solving the root causes of problems so that

they don’t recur.

The Multi-Level Learning Coach 61

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

Most readers will nd nothing conceptually di cult about this model

and may even be wondering why such a basic topic is being addressed

here. The hard part about working with groups is not helping them

understand the model, it’s helping individuals clarify what stage of the

problem- solving process they are in so that they can collaborate e ectively

at each stage. This becomes the basis for the multi- level learning coach to

intervene to help people focus on the right place at the right time. This is

consistent with the value described earlier of helping teams acquire valid

information that enables individuals to make free and informed choices.

Decision Making

Groups use a variety of ways to make decisions, some more formal than

others, and some more important than others in their scope and mag-

nitude. Yet e ective decision making is essential if people are to work

together productively in a team format. Decision making includes who

should be involved, when, in what decisions, and how the choice will be

made (Schwarz, 1994). An e ective decision has the following character-

istics: It takes all relevant data into account, team members accept it and

will work to implement it, and the decision is made in an appropriate

amount of time. Again, these characteristics are consistent with the ideals

of valid information, free and informed choice, and internal commitment.

While not all decisions need to be made by consensus, these three ideals

point to the superiority of consensus for helping people make free and

informed choices to which they are internally committed. However, time

and resource limitations don’t always enable full consensus to be achieved,

and not all decisions require such investment. The coach, team leader, and

group members should decide in advance the who, when, what, and how

of decision making before signi cant choices that a ect group members

and stakeholders in the organization have to be made.

A useful model for clarifying decision processes entails identifying who

should recommend the appropriate course of action, who should approve

the decision, who should be consulted prior to the decision’s being made,

and who should be informed after the fact. This model, called the RACI

model, helps clarify the roles of individuals inside and outside the team in

the decision- making process. In situations in which consensus is desirable

and the time can be dedicated to achieving it, all group members would

62 Roles

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

be assigned A, for approve. Often, however, a subgroup or an individual

with expertise in a speci c area may recommend a course of action to the

entire group. In such cases, this person or subgroup would be labeled R. In

still other cases, people may not want to either recommend or approve a

decision, but instead should be consulted beforehand so their opinion can

be considered. Finally, those assigned an I would not have in uence over

the decision but would be noti ed of the result in an appropriate amount

of time.

The coach can help teams establish e ective decision making not only

in team meetings, but for the project organization overall. For example,

many project groups have established “gates” through which projects

must pass, such as before systems “go live” or prior to the implementation

of recommendations on a process improvement project. Often, these deci-

sion points are critical not only for project teams, but for stakeholders in

many parts of the organization. Clari cation on who should be involved,

when, and how can help project organizations improve the way they man-

age these important milestones.

Con ict Resolution

The Chinese kanji characters for “con ict” represent both “danger” and

“opportunity.” While con ict can some times be threatening, it also opens

up avenues for collaboration that would not otherwise be possible. Con-

ict is a natural aspect of group activity that, when handled e ectively, can

promote creative solutions by combining the interests, skills, and capabili-

ties of diverse people and perspectives. From this point of view, con ict at

some level may even be necessary if organizations are to surmount sub-

stantive obstacles and deal with their most important challenges. Con ict

is de ned here simply as a situation in which two or more parties have

interests or needs that di er in some way and that need to be resolved in

order for a group to move forward. Interests and needs can be either tangi-

ble or psychological. And they must be satis ed in some way (or changed)

for the individuals involved to reach a sustainable outcome. Examples of

tangible needs include equipment, tools, and resources to perform a task.

Psychological needs include things like respect, autonomy, recognition,

belonging, and safety.

The Multi-Level Learning Coach 63

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

A useful framework for understanding the di erences in how people

relate to con ict—and a path forward for helping teams become more ef-

fective at handling it—is re ected in the dual concerns model depicted in

Figure 3.4, a version of which is incorporated into the Thomas- Kilmann

con ict mode instrument (Kilmann & Thomas, 1977). The horizontal axis

represents the degree to which an individual or group is attempting to

satisfy others’ concerns. The vertical axis represents the degree to which

someone is attempting to satisfy her own concerns. The result leads to ve

di erent styles that people bring to con ict situations: competing, avoid-

ing, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. The approach

that is most suitable for a given situation depends on the degree to which

an ongoing relationship needs to be maintained and the importance of the

outcome to participants. For example, if an individual inadvertently says

something that is irritating or o ensive to another, it may be worth avoid-

ing, given the low degree of severity and impact. However, in situations

where two or more individuals are responsible for making choices that af-

fect others in a signi cant way, such as in the case of important project de-

cisions, strategy formulation, or process designs, a collaborative approach

to negotiating a successful outcome is preferable, as it enables multiple

perspectives to be combined. No party to the decision “caves in,” tries to

“win” at the expense of others, avoids the decision, or compromises his

views to accommodate others. Rather, each fully represents her point of

view, advocating it with an appropriate level of assertiveness and with an

appropriate degree of cooperation that seeks to inquire and understand

the underlying basis for others’ points of view.

In their book Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher and William Ury (1991) out-

line a number of steps that participants can take to resolve con icts in a

collaborative way, reaching outcomes that satisfy all parties’ needs in a

win- win fashion. They help us to realize that bargaining over positions can

often lead to ine ective solutions, with results that are potentially damag-

ing to the people involved. Positions can be viewed as opening demands,

and may come in the form of something like, “We don’t have additional

resources to put into this e ort.” They can come in the form of posturing

or blaming as a way of protecting one’s own interests, as when someone

says, “You’ve consumed enough time from our department on this project

already.”

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.